Charles Haslewood Shannon stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late Victorian and Edwardian British art. An accomplished painter, a pioneering lithographer, and a key partner in the influential Vale Press, Shannon's career was interwoven with the major artistic currents of his time, including the Aesthetic Movement, Symbolism, and the revival of fine printing. His life and work, often in close collaboration with his lifelong companion Charles Ricketts, offer a fascinating window into the rich cultural milieu of fin-de-siècle London.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on April 26, 1863, in Sleaford, Lincolnshire, Charles Haslewood Shannon was the son of the Reverend Frederick William Shannon, Rector of Quarrington, and Catherine Emma Manthorp. His early life in rural Lincolnshire provided a tranquil backdrop, perhaps instilling in him a sensitivity to mood and atmosphere that would later characterize his art. His formal artistic training began in 1882 when he enrolled at the City and Guilds Technical Art School in Lambeth, London, then a burgeoning institution known for its practical approach to art education.

It was at the Lambeth School of Art that Shannon encountered Charles de Sousy Ricketts (1866–1931), a meeting that would prove to be the defining relationship of his personal and professional life. Ricketts, a precocious talent of Swiss-French and English parentage, was already demonstrating a formidable intellect and artistic vision. The two young men quickly formed an inseparable bond, united by shared artistic ideals and a deep personal affection that would last until Ricketts's death. Their partnership became one of the most celebrated and productive in British art history.

Under the tutelage of artists like George Frampton, and absorbing the prevailing influences of the time, Shannon developed his skills in drawing and painting. The London art scene was then a vibrant mix of established Royal Academicians, the lingering romanticism of the Pre-Raphaelites, and the emerging Aesthetic Movement championed by figures such as James McNeill Whistler and Oscar Wilde. Shannon and Ricketts were drawn to the ideals of "art for art's sake," emphasizing beauty, craftsmanship, and evocative subject matter over didactic moralizing.

The Enduring Partnership: Shannon and Ricketts

The relationship between Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts was foundational to both their careers. They lived and worked together for nearly fifty years, creating a shared artistic universe. Their home, first in The Vale, Chelsea, and later at Lansdowne House in Holland Park, became a salon for many leading artists, writers, and intellectuals of the day. Their collaboration was so intertwined that it is sometimes difficult to disentangle their individual contributions, particularly in their early joint ventures.

Ricketts was often seen as the more dominant, intellectually driven partner, with a flair for design, typography, and art criticism. Shannon, by contrast, was perceived as the quieter, more introspective artist, excelling in the sensuous qualities of paint and the subtle nuances of lithography. However, this is a simplification; both men were versatile and contributed significantly to their shared projects. Their partnership was one of mutual support and inspiration, allowing each to flourish in his respective strengths while contributing to a common aesthetic vision.

They collected art together, amassing an impressive collection that included works by Old Masters, Japanese prints, and Greek antiquities, all of which informed their own artistic practices. Their shared life was a testament to artistic dedication and profound companionship, navigating the societal constraints of their era with grace and discretion. This partnership was not merely a working arrangement but a deep, lifelong commitment that shaped the trajectory of British art and design at the turn of the century.

The Vale Press and The Dial: A Revolution in Book Arts

One of the most significant outcomes of the Shannon-Ricketts collaboration was the founding of the Vale Press in 1894. Inspired by the Arts and Crafts ideals of William Morris and his Kelmscott Press, Shannon and Ricketts sought to revive the art of fine bookmaking. Ricketts designed three unique typefaces for the press – Vale, Avon, and King's – and oversaw the overall design and typography, while Shannon often contributed illustrations and decorations.

The Vale Press, operational until 1904, produced over seventy exquisitely crafted books. These volumes were celebrated for their harmonious integration of type, illustration, paper, and binding, representing a pinnacle of the private press movement. Notable publications included editions of Shakespeare, Milton, Keats, Shelley, and contemporary writers like Oscar Wilde, for whom Ricketts designed several important books, including The Sphinx (1894) with its striking illustrations. Shannon's own illustrative work for the Vale Press, such as his woodcuts for Longus's Daphnis and Chloe (1893), showcased his lyrical and classical sensibilities.

Prior to the Vale Press, in 1889, Shannon and Ricketts, along with Reginald Savage, launched The Dial, an occasional art and literary magazine. Published intermittently until 1897, The Dial served as an important outlet for Symbolist art and literature, featuring contributions from artists like Lucien Pissarro (son of Camille Pissarro), Laurence Housman, and T. Sturge Moore, as well as writings by poets such as John Gray and Michael Field (the pseudonym for Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper). Shannon was a regular contributor of lithographs and drawings, helping to define the magazine's aesthetic.

The Vale Press and The Dial were not merely commercial enterprises; they were artistic manifestos, embodying Shannon and Ricketts's commitment to beauty, craftsmanship, and the integration of the arts. Their efforts significantly influenced the course of book design and illustration in Britain and beyond, setting a high standard for quality and aesthetic coherence.

Artistic Style and Influences

Charles Shannon's artistic style was a sophisticated amalgamation of various influences, filtered through his own gentle and poetic sensibility. A profound admiration for the Venetian Renaissance, particularly the works of Titian, Giorgione, and Paolo Veronese, was central to his approach. He sought to emulate their rich color harmonies, sensuous handling of paint, and idealized treatment of the human form. This Venetian influence is evident in the warmth of his palette, the soft modeling of his figures, and the often idyllic or pastoral mood of his compositions.

The legacy of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, especially the later works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Sir Edward Burne-Jones, also resonated with Shannon. He shared their interest in romantic and literary themes, their meticulous attention to detail, and their pursuit of beauty. However, Shannon's figures generally possess a more classical, less medievalized quality than those of the Pre-Raphaelites, often imbued with a languid grace.

The Aesthetic Movement, with its credo of "art for art's sake," provided the broader intellectual and artistic context for Shannon's development. Figures like James McNeill Whistler, with his emphasis on tonal harmony and decorative arrangement, and Albert Moore, with his classically draped, serene female figures, were important touchstones. Frederic Leighton, President of the Royal Academy, also championed a form of classical revivalism that found echoes in Shannon's work.

Symbolism was another crucial strand in Shannon's art. Like Continental Symbolists such as Gustave Moreau, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and Odilon Redon, Shannon was drawn to subjects that evoked mystery, dreams, and inner emotional states. His works often feature enigmatic figures in suggestive landscapes, inviting contemplation rather than offering straightforward narratives. This Symbolist tendency is particularly apparent in his lithographs.

Mastery in Lithography

While an accomplished painter, Charles Haslewood Shannon is perhaps most celebrated today for his contributions to the art of lithography. He was a key figure in the British revival of original lithography as a fine art medium at the end of the 19th century, a movement that also included artists like Whistler and Joseph Pennell. Shannon produced approximately 109 lithographs between 1888 and 1917, demonstrating a remarkable sensitivity to the medium's unique expressive possibilities.

His lithographs are characterized by their delicate tonal gradations, velvety blacks, and often dreamlike or romantic atmosphere. He favored subjects such as idyllic nudes in landscapes, mother and child groups, portraits, and allegorical scenes. Shannon often printed his lithographs in small editions, sometimes experimenting with different colored inks, such as sanguine, brown, or dark green, in addition to black. This added to the precious, intimate quality of his prints.

Works like The Ministrants (c. 1893), with its ethereal figures in a flowing procession, or The Bathers (c. 1904), depicting graceful nudes by the sea, exemplify his mastery of the medium. He achieved a remarkable softness and luminosity, exploiting the crayon's ability to create subtle textures and transitions on the lithographic stone. His prints were highly sought after by collectors and fellow artists, and they played a significant role in elevating the status of lithography in Britain. His dedication to the medium was recognized by his inclusion in important print societies and exhibitions.

Key Themes and Subjects

Throughout his career, Charles Shannon explored a consistent range of themes and subjects that reflected his artistic influences and personal inclinations. The female nude was a recurring motif, often depicted in classical or pastoral settings, embodying ideals of beauty, grace, and harmony with nature. These figures are rarely overtly erotic; instead, they possess a serene, almost sculptural quality, reminiscent of Venetian nudes or Greek statuary.

Classical mythology and Arcadian landscapes provided rich sources of inspiration. Works like Daphnis and Chloe and other compositions featuring nymphs, shepherds, and mythological figures evoke a timeless, golden age. These themes allowed Shannon to explore idealized human forms and create poetic, dream-like atmospheres, far removed from the realities of modern industrial life.

Biblical subjects also appeared in his oeuvre, often treated with a Symbolist sensibility. His painting The Wise and Foolish Virgins (c. 1920), for example, interprets the parable with a focus on mood and psychological drama rather than strict religious didacticism. The figures are imbued with a sense of introspection and quiet intensity.

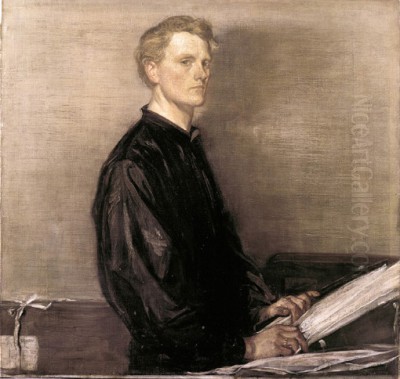

Portraiture was another important aspect of Shannon's work. He painted portraits of friends, fellow artists, and patrons, often capturing a sense of their inner life and character. His portraits, like his subject paintings, are characterized by their refined technique, harmonious color, and sensitive portrayal of the sitter. He painted a notable portrait of his partner, Charles Ricketts, as well as figures from their artistic circle.

Mother and child themes also feature prominently, particularly in his lithographs. These images are tender and intimate, often emphasizing the emotional bond between mother and child, rendered with a characteristic softness and grace.

Notable Works

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Charles Haslewood Shannon's artistic achievements:

Illustrations for Daphnis and Chloe (Vale Press, 1893): These woodcut illustrations, designed by Shannon and Ricketts and cut by them, are masterpieces of book art. They perfectly capture the pastoral romance of Longus's ancient Greek tale, with their lyrical lines and harmonious compositions. They demonstrate the Vale Press's commitment to integrating text and image.

The Wise and Foolish Virgins (Oil on canvas, c. 1920, Tate): This large-scale painting depicts the biblical parable with a Symbolist intensity. The contrasting groups of virgins are arranged in a frieze-like composition, their gestures and expressions conveying a sense of anticipation and spiritual drama. The rich colors and flowing draperies are characteristic of Shannon's mature style.

The Ministrants (Lithograph, c. 1893): One of his most famous lithographs, this work shows a procession of graceful, androgynous figures carrying offerings. The dreamlike atmosphere, soft focus, and delicate tonal range are hallmarks of Shannon's printmaking. It evokes a sense of ritual and mystery.

The Bathers (Lithograph, c. 1904): This lithograph depicts several female nudes by the sea, some emerging from the water, others resting on the shore. The figures are rendered with a classical elegance, and the overall mood is one of serene harmony between humanity and nature.

Portrait of Charles Ricketts (Oil on canvas): Shannon painted several portraits of his companion. These works are not only skillful likenesses but also intimate portrayals of their deep bond, capturing Ricketts's intellectual intensity and artistic persona.

The Infancy of Bacchus (Oil on canvas): This painting, typical of his mythological subjects, shows the young god attended by nymphs in a lush, idyllic landscape. It showcases Shannon's debt to Venetian art in its warm palette and sensuous forms.

These works, among many others, highlight Shannon's versatility as an artist, his technical skill across different media, and his consistent pursuit of beauty and poetic expression.

The Social and Artistic Milieu

Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts were central figures in the vibrant artistic and literary circles of late 19th and early 20th century London. Their home, particularly Lansdowne House, became a renowned gathering place, attracting a diverse group of creative individuals. Oscar Wilde was a close friend and associate, particularly in the 1890s, and Ricketts designed several of his books. The poet W.B. Yeats was another regular visitor and friend, whose early works were published by the Vale Press.

Other literary figures in their circle included the poet and playwright Gordon Bottomley, Michael Field (Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper), and T. Sturge Moore. Among artists, they were connected with members of the New English Art Club, such as Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert, though Shannon and Ricketts maintained a somewhat distinct aesthetic path, more aligned with Symbolism and classicism than with British Impressionism.

They also had connections with French artists and writers, including the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, whose work Ricketts deeply admired, and the writer André Gide. Their involvement with the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, of which James McNeill Whistler was the first president and Auguste Rodin a later one, further broadened their international connections. Shannon himself would later become Vice-President of this society.

The atmosphere at their gatherings was one of intellectual ferment and aesthetic debate. They discussed art, literature, theatre, and music, sharing their latest discoveries and creations. This rich social and intellectual environment undoubtedly nourished Shannon's art, providing both stimulus and support. Their extensive art collection, which included works by Old Masters like Tintoretto and Rembrandt, as well as Japanese prints and Greek vases, also served as a constant source of inspiration and study for them and their visitors.

Recognition and Institutional Affiliations

Charles Shannon's artistic achievements gained him considerable recognition during his lifetime. He exhibited regularly at prestigious venues such as the Royal Academy, the Grosvenor Gallery, the New Gallery, and the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. His work was also shown internationally, including at the Venice Biennale.

He became an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1911 and was elected a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1920. These affiliations signified his acceptance within the mainstream British art establishment, despite the sometimes avant-garde nature of his earlier work with The Dial and the Vale Press. His election to the RA was a testament to his skill as a painter, particularly in portraiture and large-scale subject pictures.

In 1918, Shannon was appointed Vice-President of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, succeeding his friend and fellow artist William Strang. This position underscored his standing not only in Britain but also within the wider European art world. His lithographs were particularly admired and collected, contributing significantly to his reputation. Works by Shannon entered major public collections, including the Tate Gallery in London, the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and numerous galleries in the UK, Europe, and North America.

Despite this recognition, Shannon remained a relatively private individual, dedicated to his art and his partnership with Ricketts. He was not a self-promoter in the vein of some of his contemporaries, preferring to let his work speak for itself. His gentle demeanor and commitment to aesthetic ideals earned him the respect and affection of many in the art world.

Later Years and Tragic Decline

The later period of Shannon's life was marked by a tragic accident that effectively ended his artistic career. In 1928, while hanging a picture at their home in Lansdowne House, he fell from a ladder, sustaining a severe head injury. The accident resulted in neurological damage, leading to a progressive decline in his mental and physical health, including dementia.

Charles Ricketts devotedly cared for Shannon during these difficult years, a period of great sorrow for both men and their circle of friends. Ricketts himself was in declining health, and the strain of caring for Shannon, coupled with his grief over his partner's condition, took its toll. Ricketts passed away in 1931, leaving Shannon in the care of their friend and executrix, Miss Edith Cooper (not to be confused with Edith Cooper of "Michael Field").

Shannon outlived Ricketts by six years, though his cognitive impairment meant he was largely unaware of his surroundings and the loss of his lifelong companion. He died on March 18, 1937, at Kew, Surrey. He was buried in St. Botolph's churchyard in his native Lincolnshire, a quiet end for an artist whose life had been so deeply embedded in the cosmopolitan art world of London. Their remarkable art collection was largely bequeathed to public institutions, most notably the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, ensuring a lasting legacy of their shared taste and connoisseurship.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Charles Haslewood Shannon's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he is remembered for his sensitive portraits, his idyllic and mythological compositions, and his adherence to a classical, Venetian-inspired aesthetic. His paintings, with their rich colors and graceful figures, offer a serene counterpoint to some of the more turbulent artistic currents of his time.

His most enduring contribution, however, is arguably in the field of printmaking. He is widely regarded as one of the foremost British lithographers of his era, a key figure in the revival of original lithography as a creative medium. His prints are admired for their technical mastery, their poetic sensibility, and their exploration of the medium's expressive potential.

Together with Charles Ricketts, Shannon played a crucial role in the private press movement through the Vale Press. Their beautifully designed and illustrated books set a new standard for book production and had a lasting impact on typography and graphic design. The Dial magazine, though short-lived, was an important vehicle for Symbolist art and literature in Britain.

Historically, Shannon is situated within the late Aesthetic Movement and British Symbolism. His work reflects the fin-de-siècle fascination with beauty, dreams, and subjective experience. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his Continental contemporaries, or as overtly modern as the Post-Impressionists who were beginning to gain attention in Britain during his later career (championed by critics like Roger Fry and artists like Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell of the Bloomsbury Group), Shannon carved out a distinctive niche. His art represents a refined and poetic vision, rooted in tradition yet imbued with a modern sensibility.

Today, his works are held in high esteem by connoisseurs of printmaking and book arts. While his paintings may be less widely known to the general public than those of some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, they continue to be appreciated for their quiet beauty and technical accomplishment. The story of his lifelong partnership with Charles Ricketts also remains a compelling example of artistic collaboration and enduring companionship.

Conclusion

Charles Haslewood Shannon was an artist of considerable talent and refined sensibility, whose contributions to British art at the turn of the 20th century were significant and varied. From his evocative paintings and masterful lithographs to his pivotal role in the Vale Press, Shannon consistently pursued an ideal of beauty and craftsmanship. His work, deeply influenced by the Venetian masters and imbued with the spirit of Symbolism and the Aesthetic Movement, offers a rich and rewarding field of study. In partnership with Charles Ricketts, he helped to shape the cultural landscape of his era, leaving behind a legacy of exquisite art and a testament to a life dedicated to aesthetic ideals. His name deserves to be remembered alongside other key figures of that fascinating period in British art history.