Francis Augustus Silva stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in nineteenth-century American art. Born in New York City on October 4, 1835, and passing away relatively young on March 31, 1886, Silva carved a distinct niche for himself within the broader currents of the Hudson River School. He became one of the most sensitive practitioners of Luminism, a uniquely American style characterized by its meticulous attention to light, serene atmosphere, and often tranquil, reflective moods. Primarily a marine painter, Silva dedicated his career to capturing the subtle beauties and quiet majesty of the Atlantic coastline, leaving behind a body of work celebrated for its poetic sensibility and masterful handling of light.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

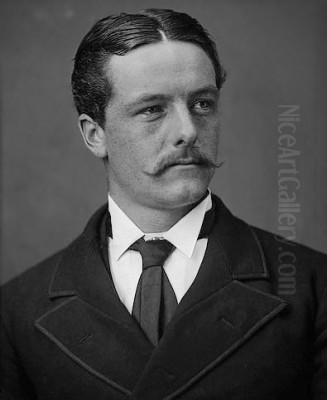

Francis Augustus Silva's origins were rooted in the immigrant experience that shaped much of New York City's identity. His father was an immigrant from Madeira, a Portuguese island, who worked as a barber, while his mother was of Irish descent. This mixed heritage contributed to what sources describe as a complex family background. From a young age, Silva displayed a clear aptitude for art, a talent noticeable enough that by the tender age of thirteen, he exhibited some of his ink drawings at the American Art Union's annual exhibition.

Despite this early promise, Silva's path to becoming a professional artist was not straightforward. His father initially harbored reservations about his son pursuing art as a viable career. However, the evident strength of Silva's talent eventually persuaded his father to relent. Lacking the means or perhaps the opportunity for formal academic training, Silva became largely self-taught. He honed his skills through observation, practice, and practical application, initially finding work in the commercial arts sphere.

Before dedicating himself fully to fine art, Silva worked as a sign painter and decorated stagecoaches and volunteer fire companies' equipment in New York City. This early commercial work, while perhaps not prestigious, likely provided him with valuable experience in handling paint, understanding composition for public display, and developing a steady hand. It was during this period, around 1855, that he reportedly first exhibited work under his own name in the city, likely pieces reflecting his burgeoning interest beyond purely commercial applications.

The Crucible of War: Service and Transformation

Silva's nascent artistic career faced a significant interruption with the outbreak of the American Civil War. In April 1861, shortly after the conflict began, he enlisted in the Seventh Regiment of the New York State Militia. He later served with the Ninth New York Infantry (Hawkins' Zouaves), eventually rising to the rank of captain. His military service took him away from his artistic pursuits for several years, immersing him in the harsh realities of conflict.

His time in the military was not without incident. At one point, Silva contracted an illness and was sent home to New York to recuperate. A misunderstanding led to him being mistakenly listed as a deserter. Although he successfully cleared his name and had his rank restored upon explaining the circumstances, the experience likely left its mark. He did not return to active duty after this episode, receiving an honorable discharge likely around 1864 or 1865.

The experience of the Civil War profoundly impacted Silva, as it did many artists and writers of his generation. While his later paintings rarely depicted overt scenes of battle or military life, the war's shadow seems to permeate his work. The pervasive sense of tranquility, the longing for peace, and the often elegiac mood found in his mature marine landscapes can be interpreted, in part, as a response to the trauma and turmoil he witnessed. His art became a vehicle for seeking harmony and stillness in a world recently torn apart by conflict.

Post-War Focus: Building a Professional Career

Returning to civilian life, Francis Augustus Silva committed himself fully to painting. The post-war years marked the true beginning of his professional fine art career. In 1868, a pivotal year for him personally and professionally, he married Margaret A. Watts. That same year, he exhibited for the first time at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York City, signaling his arrival within the established art community. He established a studio in the city, ready to make his mark.

From this point forward, Silva became a regular participant in the New York art scene. He maintained his studio in the city for many years, though he eventually settled with his family in Long Branch, New Jersey, a coastal town that likely provided ample inspiration for his marine subjects. He exhibited frequently, not only at the National Academy but also at the Brooklyn Art Association, where his works were shown almost annually between 1869 and 1880.

His involvement extended to other important arts organizations. In 1872, Silva was elected a member of the American Society of Painters in Water Colors (later the American Watercolor Society, AWS). He remained an active member until his death, regularly contributing watercolors to their exhibitions. This affiliation highlights his proficiency in watercolor, a medium well-suited to capturing the atmospheric effects he favored. He was also a member of the Artists' Fund Society, a mutual aid organization for artists, participating in their annual exhibitions as well.

The Luminist Vision: Capturing Light and Atmosphere

Francis Augustus Silva is best understood as a key figure within Luminism, a style that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, closely related to, yet distinct from, the broader Hudson River School. While artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand laid the foundations for American landscape painting, and figures like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt explored grand, dramatic vistas, Luminism offered a more intimate, quiet, and contemplative approach to nature.

Luminism, practiced by Silva and contemporaries such as Fitz Henry Lane, Martin Johnson Heade, John Frederick Kensett, and Sanford Robinson Gifford, is characterized by its profound interest in the effects of light and atmosphere. Luminist paintings often feature calm, reflective water, expansive skies, and a palpable sense of stillness. Brushwork is typically smooth and concealed, creating polished surfaces that enhance the feeling of serenity. Compositions are often horizontal, emphasizing the vastness of the landscape or seascape.

Silva excelled in this style. His paintings are renowned for their meticulous rendering of light – whether the hazy glow of dawn, the warm radiance of a sunset, or the cool clarity of moonlight on water. He masterfully captured subtle atmospheric conditions, depicting the delicate veils of mist over a harbor or the crisp air of a clear autumn day. Unlike the sometimes turbulent or overtly sublime scenes favored by earlier Hudson River School painters, Silva's work generally avoids high drama, preferring instead moments of quietude and reflection. His light is not just descriptive; it is emotive, imbuing his scenes with a sense of peace, nostalgia, or gentle melancholy.

Subject Matter: The Poetry of the American Coast

Silva's primary subject was the marine landscape of the American East Coast. He traveled and sketched along the coastline from the Chesapeake Bay in the south to Cape Ann, Massachusetts, in the north. However, he seemed particularly drawn to the shores of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. The Hudson River, the cradle of the school of painting he is associated with, also featured in his work, particularly its lower reaches near the harbor.

His canvases often depict tranquil harbors filled with sailing vessels, quiet coastal inlets, beaches under expansive skies, and iconic lighthouses standing sentinel against the sea. He had a particular fondness for scenes at dawn or dusk, times when the light is most dramatic and evocative, casting long shadows and bathing the landscape in warm or cool hues. Works like Sunrise, New York Harbor or Sunset at Tappan Zee exemplify this interest.

Among his most recognized works are paintings such as View near New London, Connecticut (1877), which showcases his ability to blend topographical accuracy with atmospheric poetry, and Robbins Reef Light (1880), a depiction of the well-known lighthouse in New York Harbor, rendered with characteristic Luminist calm and clarity. Other notable works might include scenes of Boston Harbor, Narragansett Bay, or the Shrewsbury River in New Jersey. In these paintings, the meticulously rendered ships and shoreline details are often secondary to the overall mood created by the light and atmosphere. His work offers a romanticized yet deeply felt vision of the maritime world of the late nineteenth century.

Compared to the vast, often exotic landscapes of Church or the dramatic mountain scenes of Bierstadt, Silva's focus was more intimate and localized. His paintings celebrate the specific character of the American coast, finding beauty in its working harbors and quiet shores. The stillness in his work contrasts sharply with the dynamic marine paintings of a contemporary like Winslow Homer, whose seascapes often emphasize the power and danger of the ocean. Silva sought serenity.

Artistic Circles, Connections, and Reception

While largely self-taught, Silva was not isolated from the art world. His regular participation in exhibitions at the National Academy of Design, the Brooklyn Art Association, and the American Watercolor Society placed him firmly within the professional artistic community of New York. He was associated with the Luminist painters, sharing stylistic affinities with Lane, Heade, Kensett, and Gifford. Although there's no record of formal collaboration, they were part of a shared sensibility exploring light and atmosphere.

His studio and home, particularly later in Long Branch, sometimes hosted notable figures. Sources mention visits from the renowned writer and abolitionist Frederick Douglass and the celebrated painter Winslow Homer. Such interactions suggest Silva was respected within certain cultural circles, even if he wasn't a leading figure in the academic art establishment. His connections also extended to fellow marine painters like William Trost Richards and Alfred Thompson Bricher, who explored similar coastal subjects, though often with stylistic variations.

Silva's reception during his lifetime was somewhat mixed. His work was consistently exhibited and likely found buyers, allowing him to sustain a career. He received positive notices, with critics acknowledging his skill in rendering light and atmosphere. For instance, the influential critic Kenyon Cox, writing for the New York Times, described him as a "capable minor artist" whose strength lay in conveying emotion through light. However, he never achieved the widespread fame or critical acclaim accorded to some of his contemporaries.

He was never elected an Associate or full Academician by the National Academy of Design, despite his regular participation in their exhibitions. Some critics found his work perhaps too reliant on atmospheric effects, possibly viewing his lack of formal academic training as a limitation. One particularly harsh anonymous review in The Art Review in 1885 dismissed one of his paintings as "worthless," a critique that reportedly wounded the artist. Some commentary characterized his style as "old-fashioned but charming," suggesting that by the 1870s and 1880s, as new styles like Tonalism (associated with George Inness) and Impressionism began to emerge, Silva's meticulous Luminism might have seemed somewhat conservative to progressive critics.

The inherent nature of group exhibitions meant Silva was constantly in a form of competition with other artists. Showing his work alongside dozens, sometimes hundreds, of others at the NAD or AWS annual shows required his paintings to capture attention and stand out based on their merit and appeal. While specific rivalries aren't documented, this context of constant comparison and vying for critical notice and sales was a reality for professional artists of the period, including Silva.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Significance

Francis Augustus Silva continued to paint actively throughout the 1870s and into the 1880s, primarily focusing on his signature marine subjects. He maintained his studio practice and exhibited regularly until shortly before his death. He passed away in New York City in 1886 at the age of 50 from pneumonia, cutting short a dedicated, if not always celebrated, artistic career.

In the decades immediately following his death, Silva's reputation, like that of many Hudson River School and Luminist painters, faded as tastes shifted towards Impressionism and Modernism. However, the mid-twentieth-century revival of interest in nineteenth-century American art brought renewed attention to his work. Art historians began to reassess Luminism, recognizing its unique qualities and its importance within the American landscape tradition.

Today, Francis Augustus Silva is highly regarded as one of the foremost American marine painters of his generation and a master of the Luminist style. His work is praised for its technical finesse, particularly the subtle handling of light and atmosphere, and for its evocative, poetic mood. He is seen as an artist who, perhaps influenced by his wartime experiences, sought solace and harmony in the natural world, translating these feelings into serene and beautifully crafted paintings. His lack of formal training is now often viewed not as a deficit, but as a factor that perhaps allowed him to develop a more personal and intuitive approach to his art.

His paintings are held in the permanent collections of major American museums, including the Brooklyn Museum, the New-York Historical Society, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, among others. His works are sought after by collectors and continue to be admired for their quiet beauty and technical skill.

Francis Augustus Silva's legacy lies in his contribution to the Luminist movement and his sensitive interpretations of the American coast. His paintings offer more than just picturesque views; they are imbued with a sense of time, place, and feeling. They capture a specific moment in American history and art, reflecting both the nation's enduring fascination with its natural landscapes and the introspective mood of a generation grappling with the aftermath of war. Though his career was relatively brief and his fame perhaps less widespread than some contemporaries like Homer or Inness, Silva created a distinctive and enduring body of work that secures his place as a significant figure in the story of American art. His mastery of light and his ability to evoke profound stillness ensure his paintings continue to resonate with viewers today.