Charles Meryon stands as one of the most compelling and tragic figures in 19th-century French art. Active primarily during the mid-1800s, he dedicated his unique talents almost exclusively to the medium of etching, creating hauntingly atmospheric views of Paris. His work captures a city in transition, preserving the medieval and Gothic structures that were rapidly disappearing under the urban renewal projects of the Second Empire. Meryon's life was marked by personal struggles, including debilitating colorblindness and severe mental illness, which profoundly shaped his artistic vision. Though largely unrecognized during his lifetime, his powerful etchings earned him posthumous acclaim, securing his place as a master printmaker whose work continues to fascinate viewers with its technical brilliance and psychological depth.

Early Life and Naval Aspirations

Charles Meryon was born in Paris in 1821. His parentage was unconventional for the time; his father was an English physician, Charles Lewis Meryon, and his mother, Pierre-Narcisse Chaspoux, was a dancer at the Paris Opéra. Born out of wedlock, this background may have contributed to a sense of instability that shadowed his later life. Despite these circumstances, he received an education aimed at a respectable career.

In 1837, Meryon entered the French Naval Academy at Brest. Following his training, he embarked on a naval career that included extensive travel. His service took him on voyages around the globe, most notably a circumnavigation aboard the corvette 'Le Rhin' between 1842 and 1846. This journey included significant time spent in the South Pacific, particularly in New Zealand and the French colonial outpost of Akaroa.

During these voyages, Meryon diligently sketched the landscapes, coastlines, and indigenous cultures he encountered. His drawings from New Zealand, depicting its dramatic scenery and Maori settlements, were not merely travel records. They would later serve as important source material for some of his etchings, demonstrating an early aptitude for detailed observation and draughtsmanship, even if they were later filtered through memory and imagination. However, his naval career was ultimately cut short, partly due to health issues.

The Turn to Etching: A Path Dictated by Vision

Upon returning to Paris around 1846, Meryon initially intended to pursue a career as a painter. He sought instruction and began to develop his skills in oil painting. However, a significant obstacle soon became apparent: Meryon suffered from achromatopsia, a severe form of colorblindness that rendered him unable to distinguish most colors accurately. Red, green, and blue appeared as varying shades of grey.

This condition made a career in painting, a medium heavily reliant on color perception and mixing, virtually impossible. Faced with this limitation, Meryon made the pivotal decision to abandon painting and dedicate himself entirely to the graphic arts, specifically etching. This monochromatic medium, relying on line, tone, and texture, was perfectly suited to his visual capabilities.

He sought out training in the complex techniques of etching. He studied briefly with the engraver Eugène Bléry, who specialized in landscape. Meryon learned the craft by meticulously copying the works of earlier masters, a common practice for aspiring printmakers. Among those he studied and emulated were Dutch Golden Age artists known for their detailed etchings, such as Adriaen van de Velde. This process helped him master the technical intricacies of incising lines onto a copper plate and achieving tonal variations through different biting times in acid baths.

Eaux-fortes sur Paris: Chronicling a Changing City

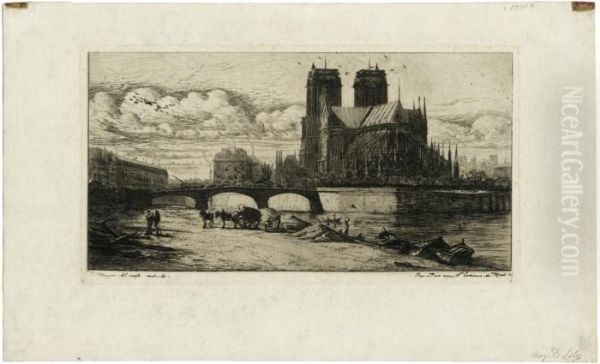

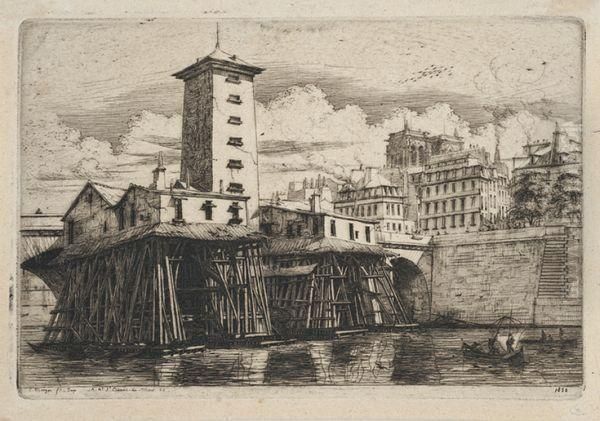

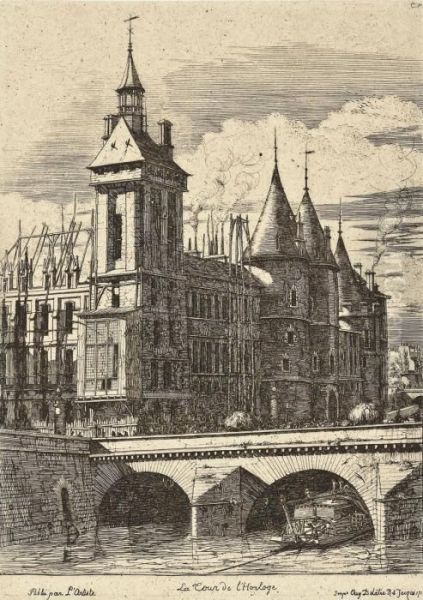

Meryon's most significant contribution to art is his series of etchings titled Eaux-fortes sur Paris (Etchings of Paris), produced mainly between 1850 and 1854. This suite of prints focused intensely on the historic heart of Paris, particularly the Île de la Cité and the surrounding quartiers. His timing was crucial; these works were created just as Baron Haussmann was beginning his massive urban renewal projects under Napoleon III, which would demolish vast swathes of medieval Paris to make way for wide boulevards and modern buildings.

Meryon's etchings, therefore, took on the quality of a poignant, almost elegiac record of a vanishing world. He was deeply fascinated by the city's Gothic architecture, finding in its weathered stones, intricate carvings, and towering structures a sense of history, mystery, and enduring presence. His perspective was far from purely documentary; he imbued his scenes with a powerful subjective and romantic sensibility.

He selected views that emphasized the grandeur, the antiquity, and sometimes the decay of these old structures. He often manipulated perspectives, exaggerated architectural features, and employed dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten the emotional impact. His Paris is not just a collection of buildings, but a living entity with a complex, often dark, soul. This series captured the imagination of a select few contemporaries and remains his most celebrated achievement.

Key Works Explored: Visions of Stone and Shadow

Within the Eaux-fortes sur Paris series and related works, several plates stand out for their technical mastery and evocative power. L'Abside de Notre-Dame de Paris (The Apse of Notre Dame, Paris, 1854) is one of his most famous images. It presents a dramatic view of the cathedral's eastern end, emphasizing its soaring buttresses and intricate Gothic structure against a turbulent sky. The viewpoint is low, making the building loom monumentally over the surrounding environment and the Seine River.

Le Petit Pont (The Little Bridge, 1850) depicts one of the ancient bridges crossing the Seine, connecting the Île de la Cité to the Left Bank. Meryon masterfully renders the textures of the old stone bridge, the surrounding buildings, and the flowing water. The composition captures the cramped, dense character of the medieval city fabric before Haussmann's interventions. The play of light and shadow creates a somber, almost melancholic atmosphere.

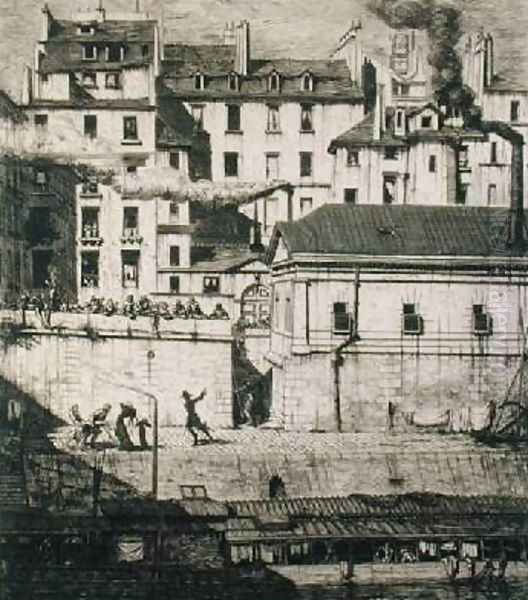

La Morgue (The Morgue, 1854) is one of Meryon's most unsettling and psychologically charged works. It depicts the grim building on the Île de la Cité where unidentified bodies were displayed for public identification. Meryon includes figures gathered outside, hinting at the morbid curiosity and human tragedy associated with the place. The stark architecture and shadowy atmosphere reflect the print's dark subject matter and perhaps Meryon's own fascination with mortality and the underbelly of city life. This work, along with others, shows hints of the mental distress that would later consume him.

Other notable works include La Pompe Notre-Dame (1852), depicting an old water pump near the cathedral with meticulous architectural detail, and Le Pont-Neuf (1853), offering a view of Paris's oldest standing bridge. La Rue des Mauvais-Garçons (The Street of the Bad Boys, 1854) captures a narrow, sinister-looking medieval street, its name alone evoking a sense of danger and decay, further enhanced by Meryon's dramatic use of shadow.

Artistic Style: Romanticism, Fantasy, and Precision

Meryon's artistic style is a unique blend of precise observation and romantic imagination. His foundation was in detailed draughtsmanship, evident in the careful rendering of architectural elements, textures, and urban topography. He possessed an extraordinary ability to translate complex structures and atmospheric effects into the linear language of etching. His lines are controlled yet expressive, capable of conveying both the solidity of stone and the ephemerality of light and shadow.

Superimposed on this realism, however, is a distinctively Romantic and sometimes fantastical sensibility. Meryon was not content merely to record; he interpreted. His Paris is often dramatic, mysterious, and imbued with a sense of history and psychological weight. This is amplified by his use of chiaroscuro, creating deep shadows and stark highlights that lend his scenes a theatrical, almost visionary quality.

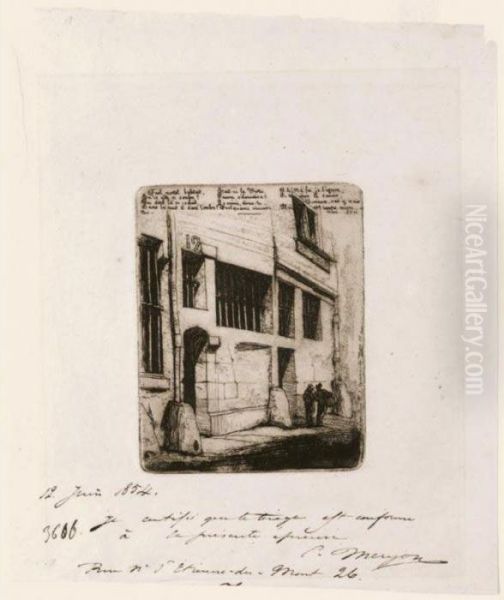

In some later states of his prints, and particularly in works created during periods of mental distress, overtly fantastical elements appear. Strange, bird-like creatures or demonic figures might populate the skies, or inscriptions bearing cryptic messages might be added to the margins or integrated into the scene itself. These additions blur the line between observation and hallucination, reflecting his deteriorating mental state but also aligning his work with the darker currents of Romanticism and prefiguring Symbolism and Surrealism. His work resonates with the architectural fantasies of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, though Meryon's focus remained firmly rooted in the specific reality of Paris.

Mental Health Struggles and Their Artistic Reflection

Charles Meryon's life was tragically overshadowed by severe and progressively worsening mental health problems. While his art provided an outlet, his psychological struggles profoundly impacted both his life and his work. Sources suggest he suffered from what might today be diagnosed as schizophrenia or a related psychotic disorder, characterized by paranoia, delusions, and hallucinations.

His condition became increasingly apparent in the late 1850s. He developed obsessive anxieties and complex, often disturbing, fantasies that interfered with his daily life and work. His behavior grew erratic, and his relationships suffered. In 1858, his mental state deteriorated to the point where he had to be committed to the Charenton asylum, a well-known psychiatric hospital outside Paris (formally known as the Maison de Santé Esquirol).

His mental illness inevitably seeped into his art. The fantastical creatures appearing in the skies of some prints, like flocks of birds transforming into fish or demons, are often interpreted as direct reflections of his hallucinations. His revisions of existing plates sometimes involved adding bizarre details or obscure symbols. While these later works are fascinating for their psychological intensity, some critics felt they lacked the clarity and power of his earlier Paris etchings.

Meryon experienced periods of remission and was released from Charenton, but he was never fully cured. He struggled immensely with poverty throughout his career. Despite the admiration of a few discerning individuals, his etchings did not sell well, and he lived in near destitution. This financial hardship undoubtedly exacerbated his mental anguish. He was readmitted to Charenton later in life and ultimately died there in 1868, reportedly having starved himself in a state of profound depression and delusion.

Contemporaries, Admirers, and Influence

Although Meryon worked in relative isolation and poverty, his unique talent did not go entirely unnoticed by perceptive figures in the Parisian art and literary world. The renowned writer Victor Hugo, himself an accomplished draughtsman with a deep love for Gothic Paris, admired Meryon's work. Hugo owned some of Meryon's prints and reportedly praised their power and authenticity.

Perhaps Meryon's most significant contemporary champion was the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire. Baudelaire, a key figure in defining modernity in art, recognized the profound originality of Meryon's vision. In his writings, Baudelaire lauded Meryon's ability to capture the "sinister and sublime" aspects of the modern city, praising the etchings for their poetic depth and psychological resonance. He saw Meryon as an artist who revealed the hidden soul of Paris.

Meryon also interacted with fellow artists. He was associated with other printmakers involved in the Etching Revival in France, such as Félix Bracquemond, who appreciated his technical skill and unique vision. His work influenced younger etchers who took Paris as their subject, like Maxime Lalanne. While not a direct tutor in the traditional sense, the landscape painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot was an early figure whose work Meryon may have studied, absorbing aspects of his approach to light and atmosphere.

His connection to Jean-François Millet, the great painter of peasant life, was indirect. Meryon studied briefly with Charles-François Phélipps, who had been a pupil of Millet, suggesting a tenuous link within the artistic lineages of the time. Meryon's work, with its blend of realism and fantasy, also finds parallels in the work of Symbolist artists like Odilon Redon, who explored dreamlike and often unsettling imagery.

While contemporaries like the Realist Gustave Courbet or the Impressionists Édouard Manet and later Paul Cézanne were revolutionizing painting, Meryon pursued his singular path in etching. His focus on urban landscapes and atmospheric effects connects him broadly to artists like James McNeill Whistler, whose later etchings of London and Venice share a sensitivity to urban mood, though Whistler's style is distinctly different. The claim of a connection to the highly successful academic painter Jean-Louis Meissonnier or figures like André de Valois appears unfounded based on available evidence. Similarly, any influence from the 18th-century painter Jean-Baptiste Greuze would be highly indirect, perhaps only through a shared French artistic heritage of depicting scenes with emotional weight.

Later Life, Death, and Posthumous Legacy

Charles Meryon's later years were marked by recurring bouts of mental illness, institutionalization, and deepening poverty. Despite the support of a few friends and admirers like Baudelaire and Bracquemond, he failed to achieve financial stability or widespread recognition during his lifetime. The public largely ignored his dark, intense visions of Paris, preferring more conventional or picturesque representations.

His final years were spent in and out of the Charenton asylum. His mental state continued to decline, and his artistic production became sporadic and often reflected his disturbed psyche. He died in the asylum on February 14, 1868, at the age of 46. The circumstances of his death, often attributed to self-starvation fueled by delusions, underscore the tragic trajectory of his life.

It was only after his death that Meryon's genius began to be fully appreciated. Collectors and critics gradually recognized the extraordinary power and originality of his Eaux-fortes sur Paris. His technical mastery of etching, his unique blend of realism and romantic fantasy, and his profound psychological engagement with his subject matter secured his reputation. His prints became highly sought after by connoisseurs.

Today, Charles Meryon is regarded as one of the greatest etchers of the 19th century. His work occupies a unique place in French art, bridging Romanticism and Symbolism. He transformed architectural depiction into a vehicle for intense personal expression, capturing the soul of a city undergoing radical transformation while simultaneously mapping the contours of his own troubled mind. His influence extended to later printmakers and artists fascinated by urban themes and psychological depth.

Conclusion: Etcher of a City's Soul

Charles Meryon's legacy is that of a visionary artist whose life was as turbulent as the Parisian cityscapes he etched onto copper plates. Forced into printmaking by colorblindness, he developed a mastery of the medium that allowed him to render the stone fabric of Paris with astonishing detail and atmospheric power. His Eaux-fortes sur Paris remains a seminal body of work, capturing the haunting beauty of medieval and Gothic Paris just before its large-scale demolition, imbued with a deeply personal, romantic, and often dark sensibility. Plagued by mental illness and poverty, his life ended tragically, but his art endured. Meryon's etchings transcend mere topography; they are profound meditations on history, memory, urban change, and the depths of the human psyche, securing his position as a unique and indispensable figure in the history of art.