Jules De Bruycker (1870-1945) stands as a significant figure in Belgian art history, a master etcher and draughtsman whose work provides a poignant and often critical window into the life, architecture, and societal shifts of his time. Born in Ghent on March 29, 1870, and passing away in the same city on September 5, 1945, De Bruycker’s life and career spanned a tumultuous period in European history, including two World Wars, the influences of which are deeply etched into his powerful imagery. A contemporary of the renowned James Ensor, De Bruycker carved his own distinct path, focusing on the urban landscapes of his beloved Ghent, the plight of its poorer inhabitants, and the haunting realities of conflict.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jules De Bruycker's journey into the world of art began in his native Ghent. At the tender age of ten, he enrolled at the prestigious Ghent Academy of Fine Arts, an institution that had nurtured many Belgian talents. However, his formal studies were prematurely interrupted by the death of his father. This personal tragedy compelled the young De Bruycker to take over the family’s upholstery and wallpaper business, a practical concern that might have extinguished a lesser artistic flame.

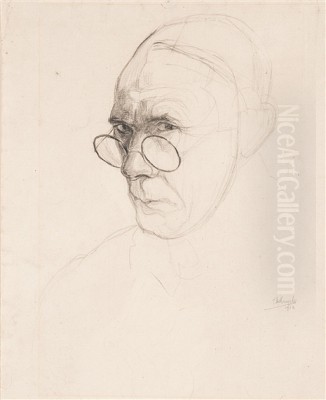

Despite the demands of commerce, De Bruycker’s passion for art remained undiminished. He continued to draw and sketch in his spare time, honing his observational skills and developing a keen eye for the human condition. His primary subjects during these formative years were the often-overlooked citizens of Ghent: the urban poor, the laborers, and the everyday people inhabiting the city's historic, yet often dilapidated, neighborhoods. He was drawn to their resilience, their struggles, and the character etched onto their faces and into the very fabric of their communities. This early focus on social realism would remain a cornerstone of his oeuvre.

The Patershol Period and Emergence

In 1902, De Bruycker made a significant move to the Patershol district of Ghent. This ancient, somewhat insular neighborhood, with its narrow, winding streets and medieval architecture, was becoming a vibrant hub for artists and writers. It was an environment that undoubtedly stimulated De Bruycker, placing him in the company of other creative minds and providing rich visual material for his work. The atmosphere of Patershol, steeped in history and alive with contemporary life, resonated deeply with his artistic sensibilities.

His first public exhibition took place in 1905, marking his formal entry into the Belgian art scene. The works displayed already showcased his burgeoning talent and thematic preoccupations. A central theme that emerged was the compelling, often stark, contrast between Ghent's ancient, imposing Gothic architecture – its cathedrals, belfries, and old guild houses – and the contemporary human dramas unfolding in their shadows. He was fascinated by how these monumental structures, symbols of past glory and enduring faith, served as backdrops to the often harsh realities of modern urban existence. His early etchings and drawings from this period, such as Wachtzaal (Waiting Room, 1906) and Op de prondelmarkt (On the Flea Market, 1906), vividly capture the life of Ghent's poorer districts, demonstrating his empathy and sharp social observation. Another notable work, Journalisten (Journalists, 1907), further exemplifies his ability to capture character and social dynamics within architectural settings.

De Bruycker’s technique, particularly in etching, was already showing remarkable sophistication. He possessed an innate ability to manipulate light and shadow, creating dramatic chiaroscuro effects that imbued his scenes with depth and emotional intensity. His lines were precise yet expressive, capable of rendering both the intricate details of a Gothic facade and the weary lines on an old woman’s face.

The Impact of War: Exile in London

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 marked a profound turning point in De Bruycker’s life and art. Like many Belgians facing the German invasion, he sought refuge abroad, fleeing to London. This period of exile, though fraught with the anxieties of war and displacement, proved to be intensely productive. The horrors of the conflict, the suffering of his homeland, and the broader human tragedy of war became dominant themes in his work.

In London, De Bruycker produced a powerful series of etchings that are considered among his most impactful and disturbing. These "war prints" moved away from the gentle social critique of his earlier Ghent scenes towards a more visceral and often nightmarish depiction of destruction, death, and despair. Works like De Dood op de kathedraal (Death on the Cathedral, 1914) are emblematic of this period. In this iconic image, the skeletal figure of Death, sometimes interpreted as a German soldier or a more universal symbol of war's devastation, looms over a Gothic cathedral, a stark representation of the desecration of culture and life.

His series on the ravaged Belgian cities, such as Ieper en Leuven (Ypres and Louvain, 1914-1918), conveyed the brutal reality of the destruction with an unflinching gaze. These works were not mere reportage; they were imbued with a profound sense of outrage and sorrow, often employing grotesque or symbolic imagery reminiscent of earlier Flemish masters like Hieronymus Bosch or Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and certainly echoing the macabre sensibilities of his contemporary, James Ensor. The influence of Francisco Goya's Disasters of War can also be discerned in the raw emotional power and critical stance of De Bruycker's wartime etchings.

His London works gained significant recognition, to the extent that the Imperial War Museum acquired a collection of these prints for its permanent archive, a testament to their artistic merit and historical significance. During this time, his style also showed an engagement with more modern artistic currents, perhaps absorbing some of the Vorticist energy present in London or the broader trends of Expressionism that were gripping Europe, evident in the work of artists like Käthe Kollwitz in Germany, who also powerfully depicted the suffering caused by war.

Return to Ghent and Mature Period

With the end of the war, De Bruycker returned to Ghent in 1919. He was a changed artist, his vision deepened and darkened by his wartime experiences. He resumed his exploration of Ghent, but his perspective was now layered with a more profound understanding of human fragility and resilience. His technical mastery continued to evolve, and his post-war works often display an even greater refinement and complexity.

In 1923, his contributions to Belgian art were formally recognized when he was made a member of the Royal Academy of Belgium. His reputation grew both nationally and internationally, with successful exhibitions of his prints and drawings in cities like Brussels and Chicago, where they received considerable critical acclaim. He was increasingly seen as one of Belgium's foremost graphic artists, a successor to the rich tradition of Flemish printmaking.

During the interwar years, De Bruycker continued to explore the interplay between architecture and humanity. Works such as De Sint-Niklaaskerk (St. Nicholas' Church, 1925) and De bedelaar Jacobus al Veur (The Beggar Jacobus at the Veur, 1927) demonstrate his enduring fascination with Ghent's historic structures and the people who lived among them. His portrayals of cathedrals were not just architectural studies; they were often imbued with a sense of brooding majesty, their ancient stones witnessing the ceaseless flow of human life, its joys, and its sorrows.

A fascinating work, though dated earlier to 1901, Papillons de nuit (Night Butterflies), executed in pastel and watercolor, reveals another facet of his talent. It depicts female figures in a nocturnal setting, hinting at themes of fashion, social mores, and the fleeting encounters of city life, showcasing his versatility beyond the starkness of black and white etching. This piece suggests an awareness of Symbolist currents, perhaps akin to the work of Fernand Khnopff or Léon Spilliaert, though De Bruycker’s approach remained rooted in a more tangible reality.

His later works sometimes took on a more abstract or symbolic quality, as seen in pieces like La Mort en Flandre (Death in Flanders, 1914, though its influence extended into his later consciousness). He continued to experiment with fantastical interpretations of landscapes and allegorical scenes, sometimes employing a surreal, dreamlike atmosphere that conveyed a sense of mystery and unease.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Techniques

Jules De Bruycker was, above all, a master of etching and drawing. His preferred medium allowed him to exploit the dramatic potential of line and shadow, creating works of extraordinary detail and atmospheric power. His style evolved from a detailed social realism in his early Ghent period, through a more expressive and sometimes grotesque symbolism during the war, to a refined and often monumental classicism in his later architectural studies.

His work is often characterized by a fusion of meticulous observation and imaginative interpretation. He could render the intricate tracery of a Gothic window with almost photographic precision, yet simultaneously imbue the scene with a palpable mood, whether it be the bustling energy of a marketplace or the desolate silence of a war-torn landscape. The "Flamengraphic" movement, a term sometimes used to describe a resurgence and emphasis on the expressive potential of etching in Flanders, certainly counts De Bruycker among its leading proponents.

De Bruycker’s art does not exist in a vacuum. He was part of a rich lineage of Flemish art that includes masters like Bruegel and Bosch, whose influence can be seen in his crowded compositions and his penchant for the grotesque or satirical. Among his contemporaries, James Ensor is the most frequently cited comparison, particularly in their shared interest in masks, skeletons, and social critique, though De Bruycker’s work generally maintained a stronger connection to observable reality than Ensor’s more fantastical visions.

He also had connections and friendships with other artists. His friendship with Frans Masereel, another towering figure in Belgian graphic art known for his powerful woodcut novels, was significant. While their primary mediums differed, they shared a profound social conscience and a commitment to using art as a means of commentary. Masereel himself acknowledged De Bruycker's influence. De Bruycker also maintained long-standing friendships with artists like Theodor Hannon and Jean Delvin, with whom he likely shared artistic dialogues and participated in creative endeavors.

The broader European artistic context also played a role. The influence of French realism and the socially conscious art of figures like Honoré Daumier can be felt in his early work. Later, his wartime experiences and his engagement with themes of death and destruction align him with a wider European trend of artists grappling with the trauma of modernity and conflict, including figures like Otto Dix and George Grosz in Germany, though De Bruycker’s style remained distinct.

Contemporaries: A Network of Artistry

The Belgian art scene during De Bruycker's lifetime was vibrant and diverse. Beyond James Ensor and Frans Masereel, several other artists formed the backdrop to his career. Figures from the Laethem-Saint-Martin school, such as Gustave Van de Woestyne, Valerius De Saedeleer, and the sculptor George Minne, were exploring different paths, often infused with Symbolism and a deep connection to the Flemish landscape and spirituality. While De Bruycker’s urban focus differed, they shared a common Belgian artistic heritage.

Expressionists like Constant Permeke, Gustave De Smet, and Frits Van den Berghe, who came to prominence particularly in the interwar period, were pushing Belgian art in new, bold directions. While De Bruycker’s style was generally more rooted in traditional representation, the expressive intensity of his war prints certainly shares some common ground with the emotional force of Expressionism. It's noted that De Bruycker had a dispute with a "Smet," likely referring to either Gustave or Léon De Smet, indicating the kind of artistic debates and rivalries common in close-knit art circles.

Other notable Belgian printmakers of the era, or those who worked significantly in graphic arts, include Félicien Rops, whose work often carried a decadent and Symbolist charge, and later, Paul Delvaux, who would become famous for his surrealist paintings but also produced graphic work. The artistic environment was rich with exchange, influence, and undoubtedly, a degree of competition for exhibitions, recognition, and patronage, as seen when De Bruycker exhibited alongside artists like Jakob Smits.

Personal Life: Challenges, Character, and Anecdotes

Jules De Bruycker’s personal life was marked by certain challenges, most notably his persistent ill health. In his later years, he suffered from osteoporosis, a debilitating condition that made the physically demanding process of etching increasingly difficult. This health issue compelled him to dedicate more of his artistic energy to drawing and painting in his final years. His physical ailments sometimes prevented him from participating in social or artistic events, as noted in anecdotes about his inability to attend certain gatherings.

Despite these struggles, De Bruycker was a keen observer of life. One anecdote describes him sitting in a café, smoking and intently watching the people around him, absorbing the nuances of human interaction – a practice that undoubtedly fueled his art. Another tells of him visiting a market with a mother and her son, with the mother showing great interest in the diverse characters present, a scene that could have come straight out of one of his market etchings.

His relationships with friends and colleagues were complex. He formed deep and lasting friendships, such as that with Frans Masereel, built on mutual respect and shared artistic concerns. However, he was also a man of strong opinions, and disagreements over artistic matters, like the mentioned dispute with Smet, were not uncommon. These interactions paint a picture of a dedicated artist, deeply engaged with his craft and the world around him, but also grappling with the physical limitations and personal vicissitudes of life. The war years, spent in exile, were undoubtedly a period of hardship, adding another layer to his personal narrative of resilience.

In 1940, despite his failing health and the ominous shadow of another war, De Bruycker completed a significant commission: a series of 22 outdoor works for the Café Wilson in Ghent. This undertaking, late in his life, speaks to his enduring creative drive and his deep connection to his city.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Jules De Bruycker passed away in Ghent on September 5, 1945, shortly after the end of the Second World War. He left behind a substantial body of work that secures his place as one of Belgium's most important graphic artists of the 20th century. His etchings and drawings are celebrated for their technical brilliance, their profound humanism, and their powerful social commentary.

His works are held in numerous prestigious collections, both in Belgium and internationally. These include the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MSK Gent), the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp (which has a strong print collection), the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, among others. This widespread institutional recognition underscores his international standing.

De Bruycker's art serves as an invaluable historical record, capturing the essence of Ghent at a particular moment in time, documenting the impact of war, and giving voice to the often-unseen members of society. His depictions of ancient cathedrals are not merely architectural renderings but profound meditations on time, history, and the human spirit. He masterfully balanced the monumental with the intimate, the grandeur of stone with the fragility of human existence.

His influence can be seen in subsequent generations of Belgian printmakers, and his work continues to resonate with contemporary audiences for its technical skill and its timeless themes of social justice, the horrors of war, and the enduring power of the human spirit. He stands as a critical link in the long and distinguished tradition of Flemish art, adapting its historical strengths to the concerns and visual language of the modern era.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Jules De Bruycker was more than just a skilled craftsman; he was an artist with a profound social conscience and a unique ability to translate his observations and emotions into powerful visual statements. From the bustling, impoverished streets of early 20th-century Ghent to the desolate, war-ravaged landscapes of Flanders, his etchings and drawings offer a compelling and often unsettling vision of his times. His deep empathy for the common person, his critical eye for social injustice, and his masterful command of the etcher's needle combine to create a body of work that is both historically significant and artistically enduring. As an art historian, one recognizes in De Bruycker a voice that, while rooted in a specific time and place, speaks to universal human experiences, ensuring his continued relevance and importance in the annals of art history.