Charles Salis Kaelin stands as a notable figure in the landscape of American art at the turn of the 20th century. An artist whose career bridged the worlds of commercial lithography and fine art painting, Kaelin is primarily recognized for his contributions to American Impressionism and his early adoption of Divisionist techniques. His dedication to capturing the nuances of the natural world, particularly the coastal scenes of New England, resulted in a body of work characterized by vibrant color, meticulous technique, and a profound sensitivity to light and atmosphere. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, key influences, significant works, and his place among his contemporaries.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in Cincinnati

Charles Salis Kaelin was born on December 18, 1858, in Cincinnati, Ohio. His familial background provided an early immersion into the world of art and design; his father was a Swiss lithographer, a profession that undoubtedly exposed young Kaelin to the technical aspects of image reproduction and graphic arts. This early environment likely fostered an appreciation for craftsmanship and visual communication. By the age of sixteen, Kaelin was already embarking on his professional journey, taking up employment at a local lithography company. This practical experience in a commercial art setting would have provided him with a solid foundation in drawing, composition, and the use of color, albeit within the constraints of print media.

His formal artistic education commenced in 1877 when he enrolled at the McMicken School of Design in Cincinnati. This institution, later to become the Art Academy of Cincinnati, was a significant center for artistic training in the Midwest. During his time there, Kaelin had the invaluable opportunity to study under influential instructors who would shape his early artistic sensibilities. Among them were Thomas Satterwhite Noble, a respected painter known for his historical and genre scenes, and, perhaps more pivotally, John Henry Twachtman.

Formative Influences: Twachtman and the Path to Impressionism

The tutelage of John Henry Twachtman was particularly significant for Kaelin's development. Twachtman, who would later become one of America's most celebrated Impressionist painters and a member of "The Ten American Painters," was at that time teaching in Cincinnati. He emphasized the importance of landscape painting and a direct, sketch-like approach, often associated with the Munich School's influence on American artists. Twachtman's own evolving style, which moved towards a more subjective and poetic interpretation of nature, deeply resonated with Kaelin. This early exposure to Twachtman's teachings instilled in Kaelin a lasting preference for natural subjects and an inclination towards expressive, rather than purely representational, art.

Kaelin's early career saw him balancing his artistic aspirations with the practical demands of commercial work. He continued to work in lithography, a field that was thriving in Cincinnati, a major publishing and printing hub. In 1893, he returned to Cincinnati to work as a designer for several prominent lithography firms, including the Strobridge Lithographing Company, known for its high-quality circus posters and advertisements. This period allowed him to hone his design skills and understanding of color impact, which would later inform his painting.

Seeking further artistic growth, Kaelin eventually moved to New York City. There, he joined the prestigious Art Students League of New York, an institution renowned for its progressive teaching methods and for attracting many of America's leading artists, both as students and instructors. The League provided a stimulating environment where Kaelin could further refine his technique and engage with the latest artistic currents. Figures like William Merritt Chase, Frank Duveneck (another Cincinnati native who had achieved international fame), and Robert Henri were associated with the League, fostering an atmosphere of dynamic artistic exploration.

Embracing Impressionism and the Allure of Divisionism

By the late 19th century, Impressionism, which had revolutionized French painting decades earlier, was gaining significant traction in the United States. American artists, many of whom had studied in Paris or at Giverny near Claude Monet, adapted Impressionist principles to the American landscape and sensibility. Kaelin was drawn to this movement, with its emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and color, and plein air painting. His work began to reflect these concerns, moving away from the tighter rendering of his earlier training towards a more broken brushwork and a brighter palette.

However, Kaelin did not merely replicate established Impressionist techniques. He became one of the early American proponents of Divisionism, a style derived from the Neo-Impressionist theories of French artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Divisionism, often closely associated with Pointillism, involved applying small, distinct dots or strokes of pure color to the canvas, intending for them to be optically mixed by the viewer's eye rather than physically mixed on the palette. This method aimed to achieve greater luminosity and vibrancy. Kaelin's adoption of this more systematic and scientific approach to color set him apart from many of his American Impressionist contemporaries.

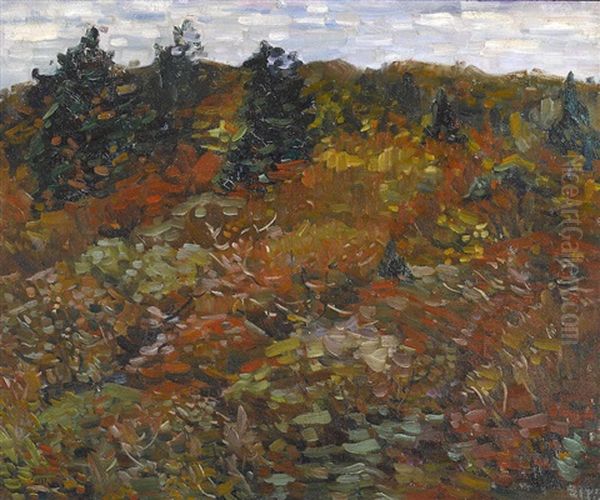

His commitment to this style was evident in his meticulous application of paint, creating surfaces that shimmered with juxtaposed hues. He was particularly adept at using this technique to convey the varied textures and light conditions of the natural world, from the dappled sunlight filtering through leaves to the reflective qualities of water and snow. While Impressionism in America was already well-established, with artists like Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and Willard Metcalf producing iconic works, Kaelin's dedication to Divisionist principles marked him as an artist willing to explore more avant-garde approaches.

The Gloucester Years and Artistic Maturity

A pivotal moment in Kaelin's career came around 1900, though some sources suggest 1902 or even later, up to 1916, when he made the decision to largely abandon commercial work and dedicate himself more fully to painting. He chose to settle in the picturesque coastal town of Gloucester, Massachusetts, on Cape Ann. This area, along with nearby Rockport, had become a magnet for artists, drawn by its rugged coastline, bustling harbor, and the unique quality of its light. Artists like Fitz Henry Lane had painted there in the mid-19th century, and by Kaelin's time, it was a thriving art colony. Winslow Homer, though further north in Maine, had also set a precedent for powerful marine painting in New England.

In Gloucester, Kaelin found an abundance of subjects that suited his artistic temperament and Divisionist technique. He became known for his depictions of the harbor, woodlands, and seasonal changes in the New England landscape. His paintings from this period are characterized by their rich, jewel-like colors and a sense of structured design, likely a lingering influence from his years in lithography. He often worked in pastel as well as oil, finding pastel particularly suited to the broken color effects of Divisionism.

His friend and fellow artist, Frank Duveneck, who had also been a significant figure in Cincinnati and had international experience, may have influenced Kaelin's approach or at least provided a supportive artistic camaraderie. Another contemporary active in the New England art scene was Theodore Wendel, who, like Kaelin, had connections to Twachtman and explored Impressionist techniques. Kaelin's commitment to his chosen style, even as new modernist movements began to emerge, was unwavering.

Notable Works and Artistic Style

Charles Salis Kaelin's body of work is distinguished by its consistent exploration of nature through the lens of Impressionist and Divisionist aesthetics. Several paintings stand out as representative of his mature style and thematic concerns.

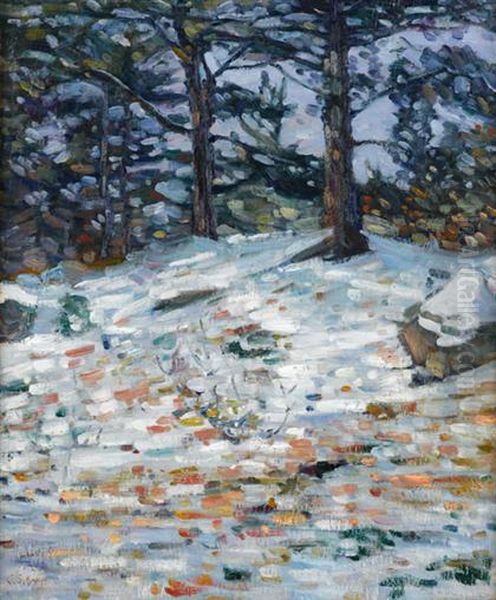

"Winter Woods" is a prime example of Kaelin's ability to capture the stark beauty of the winter landscape. Employing his Divisionist technique, he would have used a palette of cool blues, violets, and whites, accented by the warmer tones of bare branches, to convey the crisp air and filtered light of a snowy forest. The individual strokes of color would contribute to a vibrant, textured surface, making the scene come alive with subtle chromatic interactions.

"Tree in Bloom" showcases a different aspect of his artistry, likely a celebration of spring or early summer. Here, the Divisionist application of paint would serve to render the delicate blossoms and fresh foliage with a sense of airiness and light. The juxtaposition of complementary colors would create a shimmering effect, evoking the vibrancy of nature's renewal. Such a subject allowed Kaelin to explore a brighter, more varied palette, capturing the ephemeral beauty of flowering trees.

"Nocturne," another title attributed to his oeuvre, suggests an interest in the challenging effects of low light, a theme explored by James Abbott McNeill Whistler and other Tonalist and Impressionist painters. A nocturne by Kaelin, rendered in his Divisionist style, would likely involve a carefully controlled palette of deep blues, purples, and perhaps muted yellows or oranges to suggest moonlight or artificial light, with individual dabs of color creating a mysterious and evocative atmosphere.

Throughout his work, Kaelin demonstrated a profound love for nature and an almost scientific fascination with the interplay of light and color. His paintings are not merely records of a place but are personal interpretations, filtered through his unique stylistic approach. The surfaces of his canvases are often dense with carefully applied strokes, creating a tapestry of color that invites close inspection while resolving into a cohesive image from a distance.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Contemporaries

Charles Salis Kaelin's work was exhibited during his lifetime and has continued to be recognized posthumously. He participated in various exhibitions, and his paintings found their way into collections, including those of the Cincinnati Art Museum and the Butler Institute of American Art. The Cincinnati Art Museum, in his hometown, would have been an important venue for showcasing his work to a familiar audience.

In 1999, a significant resurgence of interest in his work was marked by the exhibition "Dialogues with Nature: Works by Charles Salis Kaelin (1858-1929)," which opened at the Garden of Eden gallery in New York and subsequently toured. Another exhibition in the same year, "Floral Impressions: American Artists' Views of the Flower Garden," held at the Spanierman Gallery in New York, also likely featured or contextualized his work among other artists exploring similar themes. These exhibitions helped to re-evaluate Kaelin's contribution to American art.

Kaelin worked during a vibrant period in American art history. Besides his teacher Twachtman and contemporaries like Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and Willard Metcalf (all key members of The Ten American Painters), other notable American Impressionists included Mary Cassatt, who primarily worked in France but was influential in bringing Impressionism to American collectors, and Edmund C. Tarbell. While these artists each developed individual styles, they shared a common interest in capturing the American scene with a new freshness and luminosity.

Kaelin's specific engagement with Divisionism placed him in a smaller, but significant, subgroup of American artists who experimented with Post-Impressionist ideas. While not as widely adopted in the U.S. as in Europe, Divisionism found practitioners who, like Kaelin, were intrigued by its potential for heightened color effects. His work can be seen as part of a broader exploration of color theory that also influenced artists like Maurice Prendergast, though Prendergast developed a more mosaic-like style.

The Curious Case of the Cheeseburger Claim

An unusual and somewhat tangential claim has occasionally surfaced in popular culture, linking the Kaelin name to the invention of the cheeseburger. Some accounts suggest that a Kaelin's Restaurant in Kentucky, purportedly in 1934, first introduced this culinary item. However, given that Charles Salis Kaelin, the artist, passed away in 1929, this claim cannot be attributed to him directly. It is likely a confusion with another individual or a family business that emerged later, and it remains a curious footnote, entirely separate from his artistic legacy. For the art historian, this anecdote serves as a reminder of the importance of verifying sources and distinguishing between different individuals who may share a name. The artist's life was dedicated to visual creation, not culinary innovation.

Legacy and Conclusion

Charles Salis Kaelin passed away on March 28, 1929, in Rockport, Massachusetts, the coastal area that had provided so much inspiration for his art. His legacy is that of a dedicated and skilled painter who made a distinctive contribution to American Impressionism through his committed exploration of Divisionist techniques. He successfully translated the light and atmosphere of the New England landscape into vibrant, meticulously constructed canvases that continue to engage viewers with their chromatic brilliance and sensitive observation.

While perhaps not as widely known as some of his Impressionist contemporaries who were part of groups like "The Ten," Kaelin's work holds an important place in the narrative of American art. He represents a fascinating intersection of influences: the practical discipline of lithography, the poetic landscape vision of Twachtman, and the scientific color theories of European Neo-Impressionism. His paintings serve as a testament to an artist who found his unique voice in the depiction of nature, leaving behind a body of work that reflects both the artistic currents of his time and a deeply personal connection to the American scene. His dedication to his craft and his distinctive style ensure his enduring relevance for students and enthusiasts of American art history.