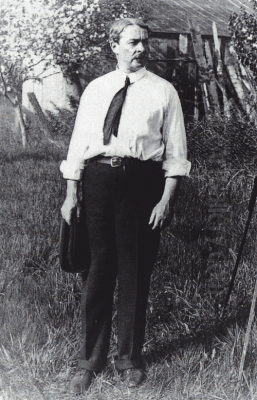

Frederick Childe Hassam stands as one of the most significant and prolific figures in American art history, particularly renowned for his contributions to the American Impressionist movement. Born during a transformative period in the United States, Hassam's long career spanned the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, capturing the vitality of modern urban life and the serene beauty of the American landscape. His distinctive style, characterized by vibrant color, dynamic brushwork, and a keen sensitivity to light and atmosphere, established him as a leading artist of his time, whose influence continues to be felt today.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Frederick Childe Hassam was born on October 17, 1859, in Dorchester, Massachusetts, which was then a town outside Boston but has since been incorporated into the city. His family had deep roots in New England. His father, Frederick Fitch Hassam, was a moderately successful hardware merchant and an avid collector of antiques. His mother, Rosa Delia Hawthorne, hailed from Maine and was related to the celebrated American author Nathaniel Hawthorne, a connection Hassam would later subtly emphasize. This lineage perhaps instilled in him a sense of connection to American cultural heritage.

Hassam displayed an early aptitude for art. However, his formal education was cut short. A devastating fire in Boston's commercial district in November 1872 severely damaged his father's business, leading to financial difficulties for the family. Consequently, Hassam left high school before graduating and sought practical employment. He initially found work in the accounting department of the publisher Little, Brown & Company, but his artistic inclinations soon led him elsewhere.

His true artistic journey began when he took up wood engraving. He apprenticed with a local engraver, George Johnson, learning the meticulous craft of translating images onto woodblocks for printing. This experience honed his skills in draftsmanship and composition. He quickly proved adept and transitioned to working as a freelance illustrator, creating designs for publications such as Harper's Weekly, Scribner's Monthly, and The Century. This commercial work provided financial support and valuable experience in visual storytelling.

Despite his practical start, Hassam harbored ambitions as a painter. He began taking evening classes at the Boston Art Club and attended the Lowell Institute. While largely self-taught in his early years, he sought instruction where he could. He studied painting under the German-born artist Ignaz Gaugengigl and began experimenting with watercolor around 1879, finding it a suitable medium for capturing fleeting effects. His early works, primarily watercolors and illustrations, already showed a sensitivity to place and atmosphere, often depicting the streets and environs of Boston.

European Sojourn and Impressionist Awakening

Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Hassam recognized the importance of European study to refine his skills and broaden his artistic horizons. In 1883, he embarked on his first trip abroad, visiting Great Britain, the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy. This initial tour exposed him to the masterpieces of European art history and diverse landscapes, enriching his visual vocabulary. He focused particularly on watercolor during this period, capturing scenes with increasing confidence.

A more pivotal journey occurred in 1886 when Hassam, accompanied by his wife, Maud Doane (whom he had married in 1884), traveled to Paris. This three-year stay proved transformative. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, studying figure drawing under Gustave Boulanger and Jules Joseph Lefebvre. While the academic training provided a solid foundation, Hassam was more profoundly influenced by the revolutionary art movements flourishing outside the official Salon system.

Paris in the 1880s was the epicenter of Impressionism. Hassam encountered the works of French masters like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and Edgar Degas. He was captivated by their innovative approach to painting: their emphasis on capturing the transient effects of light and color, their use of broken brushwork, and their focus on modern life and landscape subjects painted en plein air (outdoors). While he never fully adopted the most radical aspects of French Impressionism, its core tenets deeply resonated with him.

During his time in Paris, Hassam's style underwent a significant evolution. His palette brightened considerably, moving away from the darker, tonal qualities of his earlier Boston works. He adopted looser, more visible brushstrokes and became increasingly interested in depicting atmospheric conditions – the play of sunlight, the haze of the city, the reflections on wet pavements. He painted numerous scenes of Parisian life, capturing the boulevards, gardens, and cafes with a newfound vibrancy. He also formed connections with fellow American artists studying abroad, including John Henry Twachtman and Theodore Robinson, who were similarly exploring Impressionist ideas.

Return to America and Maturing Style

Upon returning to the United States in 1889, Hassam initially settled back in Boston but soon relocated to New York City, which was rapidly becoming the nation's cultural and artistic hub. He established a studio and quickly gained recognition for his sophisticated, light-filled paintings. He brought back the lessons learned in Paris but adapted them to American subjects and sensibilities, forging a style often described as American Impressionism.

Hassam's mature style retained the Impressionist emphasis on light, color, and atmosphere, but often with a greater sense of underlying structure and solidity compared to some of his French counterparts. His brushwork, while often quick and energetic, could also be carefully controlled to define form. He excelled at capturing the specific quality of American light, whether the crisp brightness of a New England summer day or the diffused glow of a New York streetlamp on a snowy evening.

His subject matter primarily focused on two areas: the burgeoning modern city, especially New York, and the picturesque landscapes and coastal scenes of New England. He became one of the foremost painters of urban life, depicting the bustling streets, elegant avenues, parks, and squares of New York with an eye for both their grandeur and their intimate, everyday moments. Simultaneously, he frequently retreated to the countryside and coast, finding inspiration in places like Gloucester, Massachusetts, the Isles of Shoals off the coast of New Hampshire, and Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Hassam's approach was characterized by direct observation. He often worked outdoors or from window views, seeking to capture the immediate sensory experience of a place. His paintings convey a sense of immediacy and spontaneity, yet they are underpinned by strong compositional skills developed during his years as an illustrator and engraver. He became known for his ability to render weather effects – rain, snow, fog, brilliant sunshine – with remarkable veracity and poetic feeling.

Urban Landscapes: Capturing the Modern Metropolis

Childe Hassam is perhaps most celebrated for his depictions of New York City at the turn of the twentieth century. He arrived at a time of immense growth and transformation, as the city was solidifying its status as a global metropolis. Hassam embraced the energy and dynamism of urban life, finding endless subjects in its streets, architecture, and inhabitants. Unlike some earlier artists who focused on the gritty realities of the city, Hassam often portrayed its more elegant and picturesque aspects.

Fifth Avenue, with its fashionable shops, grand residences, and streams of horse-drawn carriages (and later, automobiles), was a recurring motif. He painted it in different seasons and weather conditions, capturing the reflections on wet asphalt after rain, the soft glow of streetlights in winter twilight, or the vibrant spectacle of flags during patriotic celebrations. Works like Late Afternoon, Winter, New York (1900) exemplify his ability to convey the specific mood and atmosphere of the city through subtle modulations of color and light.

Union Square, Washington Square, Madison Square – these public spaces provided Hassam with opportunities to depict New Yorkers at leisure, strolling through parks, or navigating the urban environment. He was fascinated by the interplay of nature and architecture within the city, often framing views with trees or focusing on the patterns of light filtering through leaves onto sidewalks and buildings. His cityscapes are not just topographical records; they are evocative portrayals of the modern urban experience.

Hassam often painted from upper-story windows, giving him a vantage point that allowed for interesting compositional perspectives, looking down onto the flow of traffic and pedestrians. This perspective flattened the space in a manner reminiscent of Japanese prints, which were influential among Impressionist painters, including Hassam himself. His urban scenes capture the rhythm and pulse of the city, its constant motion, and its changing face under different atmospheric conditions.

Coastal Retreats and New England Charm

Complementing his vibrant cityscapes, Childe Hassam produced an equally significant body of work inspired by the landscapes and coastal regions of New England. He spent many summers away from the heat and bustle of New York, seeking refuge and artistic inspiration in quieter settings. These works often possess a brighter palette and a more relaxed atmosphere than his urban scenes.

The Isles of Shoals, a small group of islands off the coast of New Hampshire and Maine, became one of his most beloved subjects. He first visited in the 1880s and returned frequently over the next three decades, often staying at the salon hosted by poet Celia Thaxter on Appledore Island. Thaxter's famous garden provided a riot of color that Hassam captured in numerous paintings, such as Celia Thaxter's Garden, Isles of Shoals, Maine (1890). He also painted the rugged, sun-drenched coastline, the sparkling blue water, and the unique quality of light found on the islands. These works are among his most purely Impressionistic, filled with dazzling sunlight and vibrant hues.

Gloucester, Massachusetts, another historic New England seaport, also attracted Hassam. He painted its harbor, wharves, and the distinctive architecture of the town. His Gloucester scenes often focus on the working life of the harbor or the tranquil beauty of its surroundings, rendered with his characteristic attention to light and atmosphere.

Later in his career, Hassam became associated with the art colony in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Situated on the Lieutenant River, Old Lyme offered picturesque views of colonial architecture, gardens, and gentle landscapes. Hassam's paintings from this period often depict the stately homes and churches of the town, bathed in the soft light of summer, reflecting a sense of nostalgia and enduring American tradition. These New England works showcase Hassam's deep affection for the region's history and natural beauty, providing a counterpoint to his depictions of the modern city.

The Flag Series: Patriotism in Paint

Among Childe Hassam's most famous and celebrated works is the "Flag Series," a group of approximately thirty paintings created between 1916 and 1919. These works depict Fifth Avenue adorned with American flags and those of the Allied nations during the period surrounding the United States' involvement in World War I. Inspired by the patriotic fervor and the spectacular "Preparedness Parades," Hassam captured the visual splendor of the avenue transformed into a vibrant tapestry of red, white, and blue.

These paintings are remarkable for their dynamic compositions and energetic brushwork. Hassam used the flags not just as symbols of patriotism but as powerful abstract elements, creating rhythmic patterns of color and form that cascade down the facades of the buildings lining the avenue. The viewpoint is often elevated, looking down the canyon of skyscrapers, emphasizing the scale and grandeur of the display.

Works such as The Fourth of July, 1916 (also known as The Greatest Display of the American Flag Ever Seen in New York) and Allies Day, May 1917 are iconic examples from the series. They convey the excitement and patriotic sentiment of the era while remaining masterful studies in light, color, and atmospheric effect. The flags seem to flutter and ripple, animated by Hassam's flickering brushstrokes. Sunlight catches the vibrant colors, contrasting with the deep shadows of the buildings, creating a sense of depth and dynamism.

The Flag Series was immensely popular and cemented Hassam's reputation as a preeminent American painter. It resonated deeply with the public during a time of national crisis and unity. Beyond their historical context, these paintings stand as powerful examples of Hassam's ability to combine observational realism with the expressive potential of Impressionist technique, transforming a specific event into an enduring artistic statement.

Mastery Across Mediums: Watercolor and Printmaking

While best known for his oil paintings, Childe Hassam was also a highly accomplished master of watercolor and printmaking. His early career as an illustrator and his initial European travels saw him working extensively in watercolor. He valued the medium for its transparency and immediacy, qualities well-suited to capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, particularly in landscape and coastal scenes. His watercolors often possess a freshness and spontaneity that complements his work in oil.

Later in his career, particularly from around 1915 onwards, Hassam devoted significant energy to printmaking, becoming one of the most important American etchers and lithographers of his generation. He produced several hundred prints, revisiting many of the subjects familiar from his paintings – New York street scenes, New England landscapes, coastal views, and figure studies.

In his etchings, Hassam demonstrated a remarkable ability to translate his painterly concerns into the linear medium. He used varied patterns of lines, cross-hatching, and selective wiping of the plate to create effects of light, shadow, texture, and atmosphere. Prints like Easthampton (1917) and The Little Church Around the Corner (1924) showcase his skill in rendering architectural detail and capturing the specific mood of a place through black and white. His lithographs often explored tonal possibilities, achieving soft, atmospheric effects.

Hassam's prints were widely exhibited and collected during his lifetime, contributing significantly to the revival of fine art printmaking in America. They demonstrate his versatility as an artist and his continuous exploration of different means of visual expression. His commitment to printmaking underscored his belief in the democratic potential of the medium, allowing his work to reach a broader audience.

The Ten American Painters: A Collective Voice

Childe Hassam played a crucial role in the formation and success of "The Ten American Painters," often simply called "The Ten." This group emerged in late 1897 when Hassam, along with John Henry Twachtman and J. Alden Weir, resigned from the Society of American Artists (SAA). They felt the SAA's large annual exhibitions had become too commercialized and unwieldy, lacking a consistent artistic standard. They sought to create a smaller, more selective exhibiting group dedicated to higher aesthetic ideals.

They invited seven other artists to join them: Frank W. Benson, Joseph DeCamp, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Willard Metcalf, Robert Reid, Edward Simmons, and Edmund C. Tarbell. (William Merritt Chase was initially involved but withdrew before the first exhibition). These artists, while stylistically diverse, shared a general alignment with Impressionist or related modern tendencies and a commitment to professionalism and quality.

The Ten held their first exhibition in New York City in 1898 and continued to exhibit annually (with occasional gaps) for the next two decades, primarily in New York and Boston. Their shows were generally well-received by critics and the public, offering a more coherent and refined alternative to the sprawling SAA annuals. Hassam was a consistent and prominent contributor to these exhibitions, showcasing his latest work and reinforcing his position as a leading figure in American art.

The formation of The Ten was a significant event in the history of American art, representing a move towards artist-led initiatives and the promotion of modern styles. Hassam's involvement highlights his leadership role within the progressive wing of American art at the time and his commitment to shaping the environment in which art was exhibited and received. The group included many of the most respected painters of the era, and their collective efforts helped solidify the place of Impressionism within the American art establishment.

Artistic Relationships and Influences

Throughout his career, Childe Hassam maintained relationships with a wide network of artists, both in America and abroad. His time in Paris was crucial not only for absorbing the influence of French Impressionists like Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Degas but also for connecting with fellow Americans like Twachtman and Theodore Robinson, who shared his enthusiasm for the new style.

Back in the United States, his closest associates were often fellow members of The Ten, particularly J. Alden Weir and John Henry Twachtman. They shared aesthetic sympathies and supported each other's careers. Hassam was also friendly with other prominent figures, such as John La Farge, an older artist known for his murals and stained glass, indicating Hassam's engagement with the broader art world beyond the Impressionist circle.

His relationship with Mary Cassatt, another key figure in American Impressionism (though based primarily in France), was one of mutual respect. Both played vital roles in introducing Impressionism to American audiences and collectors. While their styles differed – Cassatt focused primarily on figures, especially mothers and children, while Hassam was more landscape and city-oriented – they shared a commitment to modern painting.

Hassam's work also shows an awareness of other artistic currents. His compositional strategies sometimes reflect the influence of Japanese prints, seen in flattened perspectives and decorative arrangements, a common interest among Impressionists. While firmly rooted in Impressionism, his later work occasionally shows a response to Post-Impressionist ideas, particularly in his printmaking, where line and form sometimes take on a more expressive, less purely descriptive quality.

Anecdotes, Personality, and Market Savvy

Childe Hassam was known for his distinct personality and certain idiosyncrasies. He made a conscious choice regarding his name, dropping his first name, Frederick, and signing his work "Childe Hassam." The name "Childe," an archaic term for a young nobleman awaiting knighthood, perhaps appealed to his sense of lineage and artistic persona. He further cultivated a unique signature by adding a crescent shape below his name, which some interpreted as a nod to a supposed, though unsubstantiated, Middle Eastern ancestry. He reportedly enjoyed the ambiguity and even embraced the nickname "Muley" (derived from Arabic titles).

He was proud of his deep New England roots and his connection, however distant, to Nathaniel Hawthorne. His family history, including a maternal grandfather who served in the Revolutionary War, likely fueled the patriotic themes evident in works like the Flag Series. Despite early financial struggles after the Boston fire, Hassam achieved considerable financial success later in his career, becoming one of the most commercially successful American artists of his time.

However, his relationship with the art market could be complex. While actively promoting his own work and understanding the importance of dealers and exhibitions, he sometimes expressed frustration with the commercial aspects of the art world. In 1911, he publicly complained about the presence of forgeries of his work on the market, highlighting the challenges faced by successful artists. He possessed a keen business sense alongside his artistic talent, carefully managing his career and reputation.

Contemporaries described Hassam as energetic, confident, and sometimes outspoken. His decision to lead the secession from the SAA to form The Ten demonstrates his willingness to challenge established structures and advocate for his artistic vision. He remained a prominent figure in the New York art world until his death.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Childe Hassam's work was widely exhibited throughout his long career, both in the United States and internationally. He began showing his work in the early 1880s at venues like the Boston Art Club and the Boston Watercolor Society. His first significant solo exhibition took place in Boston in 1887, featuring tonalist cityscapes that predated his full conversion to Impressionism.

After his return from Paris, he became a regular exhibitor at major national venues, including the National Academy of Design (though he would later distance himself from it) and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. His participation in the annual exhibitions of The Ten from 1898 onwards provided a consistent platform for his work. A major exhibition at the prestigious Montross Gallery in New York in 1904 further solidified his reputation.

Hassam also participated in significant international expositions, including the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893) and the Paris Exposition Universelle (1900), where he won medals, gaining international recognition. He exhibited multiple times at the Paris Salon. His inclusion in the landmark Armory Show of 1913, which introduced European avant-garde art to America on a large scale, placed him alongside both American contemporaries and European modernists, though Hassam himself remained skeptical of the most radical forms of modernism like Cubism.

Over his lifetime, Hassam received numerous awards and honors, cementing his status within the American art establishment. His works were acquired by major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. By the time of his death, his paintings were fixtures in important public and private collections across the country.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Frederick Childe Hassam died on August 27, 1935, in East Hampton, New York, a town he had frequently painted in his later years. He left behind an immense body of work, numbering over 3,000 pieces across various media. His legacy is multifaceted. He was undeniably a central figure in the development and popularization of Impressionism in the United States, adapting the French style to American subjects and light with unique sensitivity and skill.

His paintings of New York City remain iconic representations of the metropolis during a period of dynamic growth and change. His Flag Series stands as a powerful artistic response to a moment of national significance and a testament to his mastery of color and composition. His depictions of New England coastal and village life capture the enduring charm and beauty of the region, contributing significantly to the iconography of American landscape painting.

Beyond his own artistic output, Hassam influenced subsequent generations of American artists, particularly those working within representational traditions. His success demonstrated that an American artist could achieve both critical acclaim and popular appeal while engaging with modern artistic ideas. His commitment to printmaking also contributed to the elevation of graphic arts in America.

In a final act of support for American art, Hassam bequeathed the entire contents of his studio – several hundred paintings, watercolors, pastels, and prints – to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. This generous donation continues to support the Academy's mission and provides a valuable resource for the study of his work. Today, Childe Hassam is celebrated as one of the foremost American Impressionists, whose vibrant and evocative paintings continue to captivate audiences with their depictions of American life and landscape at the turn of the twentieth century.