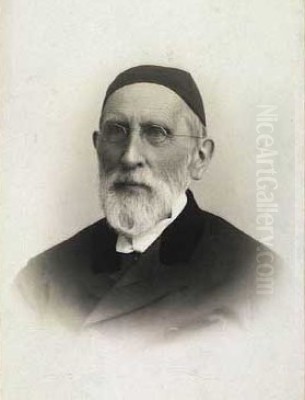

Christen Dalsgaard stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century Danish art. Born in 1824 and passing away in 1907, his life spanned a period of profound change in Denmark, both socially and artistically. He emerged during the later phase of the Danish Golden Age of painting but carved his own distinct path, becoming one of the foremost proponents of National Romanticism and a master of genre painting, particularly focusing on the depiction of rural life in his native Jutland. His work offers a valuable window into the customs, traditions, and everyday existence of the Danish people during his time, rendered with meticulous detail and quiet empathy. Beyond his artistic output, Dalsgaard also dedicated a significant portion of his life to education, influencing subsequent generations.

Early Life and Formative Years

Christen Dalsgaard was born on October 30, 1824, at Krabbesholm Manor near Skive, situated on the Salling peninsula in Jutland. His father, Jens Dalsgaard, was the estate owner, providing a comfortable, albeit rural, upbringing for the young Christen. From an early age, he displayed a clear aptitude for art. Initially, he received some training as a craft painter, a practical foundation that perhaps instilled in him an appreciation for careful workmanship and detail that would become characteristic of his later fine art.

A pivotal moment came when the landscape painter Niels Rademacher visited his home region. Recognizing the young man's potential, Rademacher encouraged Dalsgaard to pursue formal art training in the capital. Heeding this advice, Dalsgaard moved to Copenhagen in 1841 to enroll at the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi). This move placed him at the heart of the Danish art world during the flourishing Golden Age.

At the Academy, Dalsgaard benefited from the tutelage of some of the era's leading figures. He studied under the renowned Martinus Rørbye, a painter known for his genre scenes and travel paintings, who provided Dalsgaard with private lessons before becoming a professor at the Academy's model school in 1844. Perhaps most significantly, Dalsgaard also came under the influence of Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, widely regarded as the "Father of Danish Painting" and the central figure of the Golden Age. Eckersberg's emphasis on careful observation, precise draughtsmanship, and the study of nature profoundly shaped the Academy's curriculum and left an indelible mark on his students, including Dalsgaard. He was admitted to the Academy's free painting school in 1846 and made his debut at the esteemed Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition in 1847, marking the official start of his public career.

Embracing National Romanticism

Dalsgaard's artistic development occurred against a backdrop of rising national consciousness in Denmark. The Napoleonic Wars and the loss of Norway in 1814 had spurred a desire to define and celebrate a unique Danish identity. This sentiment found powerful expression in the arts through the National Romantic movement. A key intellectual force behind this was the influential art historian Niels Laurits Høyen. Høyen passionately advocated for Danish artists to turn away from foreign models and classical themes, urging them instead to find inspiration in their own country's landscapes, history, and, crucially, the lives of its ordinary people, particularly the peasantry who were seen as preserving authentic national traditions.

Dalsgaard deeply absorbed Høyen's ideas. Unlike many artists of previous generations who considered a study trip to Italy essential, Dalsgaard made a conscious decision to focus his artistic gaze inward, on Denmark itself. He found his richest source material in the rural communities of his native Jutland. His commitment was not just to depict Danish scenes but to do so with an authenticity that captured the specific character of the region and its inhabitants. This alignment with Høyen's program positioned Dalsgaard as a leading figure in the National Romantic current within Danish painting.

His paintings became celebrations of Danish folk life, documenting local customs, traditional costumes, and the rhythms of rural existence. He approached his subjects with a blend of romantic idealization and realistic observation, seeking to portray the dignity and quiet virtue he perceived in the lives of the country folk. This focus distinguished him from some earlier Golden Age painters who might have concentrated more on urban scenes, portraiture of the bourgeoisie, or purely classical landscapes.

The Painter of Jutland's Soul

The core of Christen Dalsgaard's artistic legacy lies in his genre paintings depicting the people and landscapes of Jutland. He possessed a remarkable eye for detail, meticulously rendering the textures of fabrics, the specific construction of furniture and tools, the interiors of farmhouses, and the nuances of local dress. This almost ethnographic precision gives his works immense historical value, preserving a visual record of a way of life that was beginning to change even during his lifetime.

His paintings often tell quiet stories, focusing on moments of everyday life imbued with subtle emotion. One of his most famous works, Mormoner på besøg hos en tømrer på landet (Mormons Visiting a Country Carpenter, 1856), exemplifies this. It depicts two Mormon missionaries engaging with a skeptical-looking carpenter and his family in their workshop. The painting captures a specific contemporary social phenomenon – the arrival of Mormon missionaries in rural Denmark – while also exploring themes of faith, community, and cultural encounter through the carefully observed interactions and expressions of the figures.

Another poignant example is En landsbysnedker bringer ligkisten til det døde barn (A Village Carpenter Bringing the Coffin for the Dead Child, 1856). This work tackles a somber theme with sensitivity and restraint. The focus is on the solemnity of the occasion and the quiet grief of the community, conveyed through the postures of the figures and the subdued atmosphere of the scene. It avoids melodrama, instead finding emotional weight in the realistic portrayal of a difficult but common aspect of rural life.

The painting Mon, han dog ikke skulle komme? (Wonder if he isn't coming home after all?, 1879) shows a young woman gazing wistfully out of a window, awaiting someone's return. The detailed interior, the play of light, and the woman's contemplative pose create a powerful sense of longing and domestic intimacy. Dalsgaard excelled at capturing these internal emotional states through external observation.

In his focus on folk life, Dalsgaard shared thematic ground with contemporaries like Julius Exner and Frederik Vermehren. Exner often depicted more cheerful and anecdotal scenes from rural life, particularly on the island of Amager, while Vermehren shared Dalsgaard's seriousness and detailed realism, often focusing on the inhabitants of Jutland as well. While their approaches differed in nuances of mood and composition, all three artists contributed significantly to the rich tapestry of Danish genre painting in the mid-to-late 19th century.

Faith and Folk: Religious Commissions

Beyond his celebrated genre scenes, Christen Dalsgaard also made significant contributions to religious art in Denmark. His work in this area was closely linked to the Grundtvigian movement, a major religious and cultural revival initiated by the theologian, poet, and historian N.F.S. Grundtvig. Grundtvigianism emphasized a joyful, life-affirming Christianity deeply rooted in Danish history, mythology, and folk culture. It promoted the establishment of folk high schools and independent congregations (Valgmenigheder) outside the strict control of the state church.

Dalsgaard became one of the foremost painters associated with the Grundtvigian movement. He received numerous commissions for altarpieces and other religious works for churches sympathetic to Grundtvigian ideals. In these works, he often sought to bridge the gap between biblical narratives and the familiar world of his Danish audience. He might depict biblical figures with features reminiscent of Danish peasants or place sacred events within recognizable Danish landscapes or interiors.

A notable example is the altarpiece Madonna and Child painted for the Skive Church in 1869. While adhering to the traditional subject matter, his treatment likely infused it with a warmth and accessibility resonant with Grundtvigian sensibilities. He also created works like Den hellige familie i Nazareth (The Holy Family in Nazareth) for the Ryslinge Valgmenighedskirche, portraying the domestic life of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph with a simplicity and tenderness that emphasized the human aspects of the divine narrative. His religious art, therefore, was not merely devotional but also served as a visual expression of the Grundtvigian synthesis of faith, folk culture, and national identity.

A Life in Education: The Sorø Years

In 1862, Dalsgaard took on a new role that would occupy him for the rest of his life: he was appointed as a drawing master at Sorø Academy (Sorø Akademi). Located in the town of Sorø on Zealand, this prestigious boarding school had a long history and was known for its high academic standards. His position there provided him with financial stability and a connection to the intellectual life outside the immediate Copenhagen art scene. Sorø itself had associations with the Grundtvigian movement, making it a fitting environment for Dalsgaard.

He remained at Sorø Academy, teaching drawing, until his death in 1907, a tenure spanning over four decades. While detailed records of his specific pedagogical methods or a comprehensive list of students who became prominent artists under his direct tutelage might be scarce, his long service undoubtedly had an impact. Teaching requires a constant engagement with the fundamentals of art, which may have reinforced aspects of his own practice.

One notable figure associated with Sorø during Dalsgaard's time there was Jeppe Aakjær, who would become one of Denmark's most beloved poets and novelists, known for his realistic and socially conscious depictions of Jutland peasant life. While primarily celebrated for his literary achievements, Aakjær did attend Sorø Academy and likely received drawing instruction from Dalsgaard. This connection underscores the cultural milieu in which Dalsgaard operated. His role as an educator cemented his position as a respected figure within Danish cultural life, extending his influence beyond the canvas. In 1892, his long contribution was formally recognized when he was appointed Professor at Sorø.

Style, Technique, and Vision

Christen Dalsgaard's artistic style is characterized by a careful synthesis of realism and romanticism. His grounding in the academic tradition, particularly under Eckersberg, is evident in his strong draughtsmanship and attention to accurate representation. However, he imbued this technical skill with a romantic sensibility, particularly in his choice of subject matter and his empathetic portrayal of rural life.

His commitment to detail was paramount. Whether depicting the weave of homespun cloth, the grain of wood in a carpenter's workshop, or the specific wildflowers growing in a Jutland field, Dalsgaard rendered his subjects with meticulous care. This realism extended to his portrayal of people; while sometimes idealized in their virtue, their features, clothing, and postures were based on close observation of the local population.

His use of light is often subtle but effective. He frequently depicted interior scenes, using light filtering through windows or emanating from lamps to define space, create mood, and highlight key figures or objects. The light in his paintings is typically calm and clear, contributing to the overall sense of order and tranquility often found in his work. His color palette tended towards naturalistic and sometimes subdued tones, reflecting the earthy hues of the rural environment, though he could use color effectively to draw attention or enhance the emotional atmosphere.

What elevates Dalsgaard's work beyond mere documentation is his psychological insight. He was adept at capturing the inner lives of his subjects through their expressions, gestures, and interactions. The quiet contemplation of the woman in Mon, han dog ikke skulle komme?, the skepticism of the carpenter meeting the Mormons, the shared grief surrounding the child's coffin – these emotional nuances are conveyed with subtlety and conviction.

Compared to some contemporaries, his focus remained consistently on the human element within the Danish landscape. While artists like P.C. Skovgaard and Johan Thomas Lundbye became renowned for their majestic and often romantically charged depictions of Danish nature itself, Dalsgaard's landscapes typically served as settings for human activity. Similarly, while Constantin Hansen explored grand historical and mythological themes inspired by his time in Rome, Dalsgaard remained dedicated to the humbler narratives of his homeland. His vision was intimate, focused, and deeply connected to the specific culture he chose to represent.

Recognition and Final Years

Christen Dalsgaard achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. His regular participation in the Charlottenborg exhibitions kept his work in the public eye. He received several prestigious awards, including the Neuhausen Prize in 1856, an important early career acknowledgment. Perhaps the most significant honor was the Thorvaldsen Medal, Denmark's highest cultural award within the visual arts, which he received in 1861. This award cemented his status as one of the leading painters of his generation.

He continued to paint actively throughout his long tenure at Sorø Academy. His works were included in major exhibitions both in Denmark and abroad, often shown alongside those of his peers like the animal and battle painter Jørgen Sonne and the landscape and genre painter Vilhelm Kyhn. His professorship, granted in 1892, was a further testament to the respect he commanded within the Danish art establishment.

He remained in Sorø until the end of his life, passing away there on February 11, 1907, at the age of 82. He left behind a substantial body of work that had consistently explored and celebrated the life and culture of rural Denmark, particularly his beloved Jutland.

Legacy in Danish Art

Christen Dalsgaard occupies a vital place in the history of Danish art. He serves as a bridge figure, rooted in the traditions of the Golden Age learned from Eckersberg and Rørbye, but pushing forward into the detailed realism and national focus that characterized the later 19th century. He stands as one of the most important interpreters of Danish folk life, creating works that are both aesthetically pleasing and invaluable historical documents.

His contribution to National Romanticism was profound. Alongside artists like Peter Raadsig or the slightly earlier landscape painter Dankvart Dreyer, Dalsgaard helped define a visual identity for Denmark that celebrated its unique character and traditions. His dedication to depicting the lives of ordinary Danes, particularly the peasantry of Jutland, resonated deeply with the cultural currents of his time and helped shape the nation's self-image.

Furthermore, his role as a key artist of the Grundtvigian movement highlights the intersection of art, religion, and national identity in 19th-century Denmark. His religious works provided visual expression for Grundtvig's ideas, integrating faith with folk culture in a way that was both innovative and deeply felt.

Today, Dalsgaard's paintings are held in high esteem and can be found in major Danish art museums, including the Statens Museum for Kunst (National Gallery of Denmark) and numerous regional collections. His works continue to be appreciated for their technical skill, their detailed observation, their quiet emotional depth, and the enduring window they offer onto the soul of 19th-century rural Denmark. He remains a key figure alongside the major names of his era, recognized for his unique focus and lasting contribution.

Conclusion

Christen Dalsgaard's long and productive career was dedicated to capturing the essence of Danish rural life, particularly in Jutland. Through his meticulous genre paintings and his sensitive religious works, he became a defining artist of National Romanticism and a visual chronicler of a nation's identity. Influenced by the masters of the Golden Age yet forging his own path, and deeply connected to the cultural and religious movements of his time, Dalsgaard created a body of work characterized by detailed realism, empathetic observation, and quiet dignity. His paintings remain a testament to his skill and vision, securing his enduring importance within the rich history of Danish art.