Léopold-Louis Robert stands as a significant figure in early 19th-century European art, a Swiss painter whose life and work were deeply intertwined with the landscapes, people, and burgeoning Romantic sensibilities of his time. Born on May 13, 1794, in La Chaux-de-Fonds, within the Neuchâtel region of Switzerland, Robert's artistic journey would take him from the disciplined studios of Paris to the sun-drenched vistas and vibrant folk culture of Italy. His legacy is primarily built upon his evocative genre scenes, particularly those depicting Italian peasant life and the then-notorious brigands, rendered with a unique blend of Neoclassical training and Romantic feeling. His relatively short but impactful career ended tragically with his death in Venice on March 20, 1835.

Early Life and Parisian Training

Robert's formative artistic education took place in Paris, the epicenter of European art at the turn of the 19th century. He had the crucial opportunity to study under the tutelage of Jacques-Louis David, the leading proponent of Neoclassicism and arguably the most influential painter in Europe at the time. David's studio was a crucible of artistic talent and rigorous training, emphasizing strong draftsmanship, clarity of form, historical and mythological subjects, and a sense of moral gravity.

Immersion in this environment provided Robert with a solid technical foundation. He learned the Neoclassical emphasis on line, composition, and the idealization of the human form. Fellow artists who passed through David's demanding atelier, or were prominent contemporaries absorbing or reacting to his influence, included future luminaries like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, known for his linear precision and refined classicism, Antoine-Jean Gros, who bridged Neoclassicism with early Romantic dynamism in his Napoleonic scenes, and François Gérard, celebrated for his elegant portraits of European aristocracy and historical paintings. Robert absorbed the discipline of this school, a grounding that would remain visible even as his style evolved.

The Italian Sojourn: A New Artistic Vision

A pivotal moment in Robert's life and career occurred in 1818 when he relocated to Italy. This move marked a significant shift in his artistic focus and thematic interests. He spent considerable time in Rome and Naples, immersing himself in the local culture and landscapes. Italy, for many Northern European artists of the Romantic era, represented a land of classical ruins, intense light, passionate people, and a perceived connection to a more authentic, pre-industrial way of life. Robert was captivated.

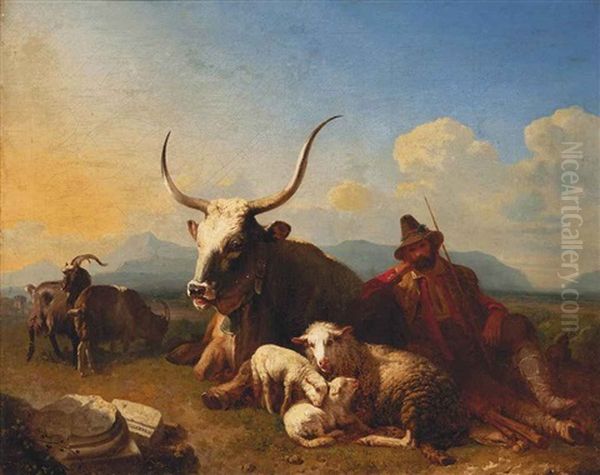

He turned his attention away from the grand historical narratives favored by strict Neoclassicism and towards the depiction of contemporary Italian life. He became particularly renowned for his paintings of peasants, fishermen, and, most famously, the brigands or bandits who roamed the Italian countryside. These figures, often romanticized in the popular imagination of the time, offered subjects full of character, drama, and picturesque potential. Robert sought authenticity, observing local customs, festivals, and daily activities with a keen eye.

His dedication to capturing the reality of his subjects extended to gaining special permission to enter locations like the Castel Sant'Angelo and the Termini prisons in Rome. Here, he could sketch detained brigands directly, lending his later paintings a degree of observed detail and character study that distinguished them from purely imagined scenes. This direct engagement with his subjects, even those on the margins of society, was characteristic of his approach during his Italian years. While in Rome, he would have been aware of other artistic currents, such as the German Nazarene painters like Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius, who sought spiritual renewal through a revival of early Renaissance styles, though Robert's path remained distinct, focused on contemporary genre.

Major Works and Artistic Style

Robert's time in Italy yielded his most celebrated works, often characterized by vibrant color, emotional depth, and a careful balance between observed reality and artistic idealization. He conceived a series of large canvases intended to represent the four seasons through the lens of Italian folk life, although only three were substantially completed.

The Return from the Pilgrimage to the Madonna dell'Arco (often cited as Fête de la Madone d'Arco), representing Spring, depicts a joyous Neapolitan festival scene, bursting with life, color, and movement. It showcases his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and capture a sense of communal celebration. This work was highly acclaimed when exhibited.

The Reapers Arriving in the Pontine Marshes (Reapers of the Ponte Marshes), representing Summer, portrays agricultural laborers with a sense of dignity and monumentality, set against a specific Italian landscape. The painting combines detailed observation of costume and activity with a slightly idealized, heroic portrayal of peasant life.

The Departure of the Fishermen of the Adriatic, intended to represent Winter, remained unfinished at the time of his death. Even in its incomplete state, it conveys a mood of somber anticipation and captures the atmosphere of the coast.

Beyond this ambitious cycle, other works cemented his reputation. Jeune fille de Sonnino (Young Girl of Sonnino) is noted for its sensitive portrayal of the subject, rich color, and detailed rendering of regional costume, likely drawing on the area's association with brigands for added Romantic allure. Amoureux napolitains et leur fils (Neapolitan Lovers and their Son) exemplifies his focus on intimate family scenes within the Italian setting, showcasing tenderness and regional character.

Robert's style is often described as a bridge between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. From his Davidian training, he retained a clarity of composition and a careful attention to drawing. However, his embrace of contemporary, often rustic or exotic subjects, his heightened use of color, his focus on emotional expression, and the dramatic potential of his themes align him firmly with the burgeoning Romantic movement. His work contrasts with the cooler, more detached classicism of Ingres, and while sharing a Romantic spirit, it differs from the turbulent energy and painterly freedom found in the works of French Romantics like Eugène Delacroix or Théodore Géricault. Robert carved a niche focused on the picturesque and dramatic aspects of Italian folk life.

The Brigand Theme: Romanticism and Reality

Robert's depictions of Italian brigands became one of his most popular and defining subjects. In the early 19th century, these figures occupied a complex space in the European imagination – seen simultaneously as dangerous criminals and as symbols of freedom, rebellion, and rugged individualism, living outside the constraints of conventional society. This ambiguity made them compelling subjects for Romantic artists, writers, and audiences.

Robert capitalized on this interest, but his approach was grounded in observation. His visits to prisons allowed him to study the physiognomy, attire, and bearing of actual brigands. Paintings like Le Brigand en prière (The Brigand Praying) or studies simply titled Le Brigand (like the one dated 1822, now in Geneva) portray these figures with a striking intensity. He often depicted them not in acts of violence, but in moments of contemplation, repose, or familial connection, adding psychological depth to the stereotype.

These works were praised for their ethnographic detail – the specific rendering of costumes, weapons, and settings – combined with a dramatic flair. The vivid colors, strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and expressive poses contributed to their impact. Robert managed to satisfy the public's appetite for the exotic and dangerous while lending his subjects a degree of humanity and realism derived from his direct studies. This specific focus set him apart and contributed significantly to his fame.

Fame, Reception, and Contemporary Context

Léopold-Louis Robert achieved considerable fame during his lifetime. His paintings were eagerly anticipated at the Paris Salons, the official art exhibitions that were crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success. The exhibition of works like The Return from the Pilgrimage to the Madonna dell'Arco at the Salon of 1827 was a triumph, and his success continued into the early 1830s. After the 1831 Salon, he was considered one of the most popular painters in France and his fame spread to Germany and beyond.

His work resonated with the public's growing taste for Romantic themes: exotic locales, dramatic narratives, and emotionally charged scenes. His detailed, colorful depictions of Italy offered a form of escapism and satisfied a curiosity about distant lands and cultures. His ability to capture the specifics of Italian peasant and brigand life was widely admired. He achieved a level of popular acclaim comparable to artists like Horace Vernet, who also specialized in contemporary subjects and dramatic scenes, though Vernet's focus often leaned more towards military themes.

However, Robert's work was not without its critics. Some commentators, particularly those adhering strictly to Neoclassical or academic principles, found his compositions occasionally stiff or his figures lacking the idealized perfection of the high classical tradition. They sometimes perceived his detailed realism as overly descriptive or anecdotal, lacking the universal significance of historical or mythological painting. Despite these critiques, his position as a leading figure of his generation, particularly in the realm of genre painting with Romantic overtones, was undeniable.

Personal Turmoil and Tragic End

Behind the public success, Robert's personal life was marked by emotional intensity and ultimately, tragedy. Sources consistently point to a profound and troubled relationship with Princess Charlotte Bonaparte, the niece of Napoleon I and daughter of Joseph Bonaparte. Charlotte was herself an amateur artist and moved in artistic circles. Robert appears to have developed a deep, perhaps unrequited or impossible, passion for her.

The complexities of this relationship, possibly compounded by pressures related to social status, personal insecurities, and recurring bouts of melancholia or depression that afflicted Robert, took a heavy toll on his mental state. His letters often reveal a sensitive, perhaps overly anxious temperament, prone to periods of despair. This inner turmoil contrasted sharply with the often vibrant and seemingly joyous scenes he depicted in his art.

The culmination of these struggles occurred in Venice. On March 20, 1835, just a week after his 41st birthday, Léopold-Louis Robert took his own life. He died in a Venetian palace, leaving behind his unfinished final major work, The Departure of the Fishermen of the Adriatic. His suicide shocked the art world, adding a layer of Romantic tragedy to his already dramatic life story and cementing his image as a sensitive soul overwhelmed by passion and despair, an archetype popular in the Romantic era. The less substantiated story connecting his distress to an earlier infatuation with Marie Antoinette seems less likely than the well-documented and emotionally devastating involvement with Charlotte Bonaparte.

Legacy, Influence, and Collections

Léopold-Louis Robert left a distinct mark on 19th-century art. His primary contribution lies in his popularization and elevation of Italian genre painting. He brought a new level of detail, ethnographic accuracy, and emotional resonance to scenes of everyday life, moving beyond the generalized Arcadian peasants of earlier traditions. His work captured a specific time and place with a unique blend of realism and Romantic idealization.

His influence can be seen in the continued interest in Italian folk subjects among later 19th-century painters. While direct stylistic followers might be few, his success demonstrated the public appetite for well-executed genre scenes depicting foreign cultures. Artists specializing in detailed historical or exotic genre, like the later French academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, although focused more on Orientalist themes, operated in a field where Robert had already proven the potential for popular and critical success with meticulously rendered scenes of specific cultural milieus. His work also stands alongside that of other popular Romantic-era painters like Ary Scheffer, who similarly explored themes of emotion and historical sentiment.

Today, Robert's works are held in major museum collections across Europe. The Musée d'Art et d'Histoire in Geneva holds important pieces like Le Brigand (1822). The Neue Pinakothek in Munich includes his work, notably as part of the historic Sammlung Graf Raczynski. His birthplace, La Chaux-de-Fonds, honors him with collections and exhibitions at its Musée des Beaux-Arts, such as the recent "Léopold Robert - un état des lieux." The Musée de la Vie Romantique in Paris holds memorabilia related to the era, including potentially a sculpture linked to him. His paintings continue to appear at auction, demonstrating sustained interest.

Conclusion

Léopold-Louis Robert's career, though tragically cut short, remains significant. As a Swiss artist trained in the Neoclassical rigor of David's studio, he forged a unique path by applying his skills to the vibrant, contemporary life of Italy. He became a master chronicler of Italian folk culture, particularly famed for his dramatic depictions of brigands and his colorful festival and peasant scenes. His ability to blend detailed observation with Romantic emotion resonated deeply with his contemporaries, earning him widespread fame. His dramatic life, marked by intense passion and deep melancholy culminating in suicide, only added to his Romantic aura. Robert stands as a key figure in the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism, an artist who captured the specific allure of Italy for the 19th-century imagination and left behind a body of work admired for its technical skill, ethnographic interest, and emotional power.