Clarice Marjoribanks Beckett stands as one of Australia's most intriguing and ultimately significant early modernist painters. Working in the first decades of the 20th century, she developed a unique and highly sensitive visual language focused on capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere in the suburban and coastal landscapes around Melbourne. Initially overlooked and misunderstood by many of her contemporaries, her work underwent a remarkable posthumous rediscovery, securing her place as a pivotal figure whose quiet, contemplative paintings offer a distinct counterpoint to the more heroic narratives often dominating Australian art history. Her life (1887-1935) was one of quiet dedication, marked by personal sacrifice and an unwavering commitment to her artistic vision, resulting in a body of work celebrated today for its subtlety, poetry, and innovative approach to representation.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Clarice Beckett was born in Casterton, a rural town in western Victoria, Australia, in 1887. Her family background was relatively comfortable; her father, Joseph Beckett, was a bank manager, and her mother, Elizabeth (née Brown), came from a prominent Melbourne family. Notably, her maternal grandfather, John Brown, was the architect who designed and built the significant historic mansion, Como House, in South Yarra, suggesting an underlying connection to aesthetics and design within the family lineage, even if direct artistic pursuits were not initially encouraged for Clarice.

From a young age, Beckett displayed a quiet, introspective personality, often described as shy and reserved. This temperament would seemingly shape both her life choices and her artistic sensibility. While she showed an early interest in art, her path towards formal training was not straightforward. Her father, reflecting perhaps the societal expectations for women of his time, initially harboured reservations about his daughter pursuing art seriously.

It wasn't until Beckett was in her late twenties, around 1914, that she received the family support needed to enrol at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School in Melbourne. This delay meant she began her formal artistic education later than many of her peers, but she entered it with a maturity that perhaps contributed to the focus and dedication she would soon display. Her time at the Gallery School, lasting until 1917, provided her with foundational skills, but it was her subsequent association with the controversial artist and teacher Max Meldrum that would prove most decisive in shaping her artistic direction.

The Influence of Max Meldrum and Tonalism

After her studies at the National Gallery School, Clarice Beckett sought further instruction under Max Meldrum, a charismatic and dogmatic figure in the Melbourne art scene. Meldrum had developed a quasi-scientific theory of painting he termed "Tonalism." This approach eschewed traditional emphasis on colour and line in favour of meticulously rendering tonal values – the relative degrees of light and dark – as observed through optical analysis. Meldrum advocated for painting directly from nature, often with a limited palette, aiming for objective representation based on visual perception rather than emotional expression or decorative effect.

Meldrum's theories were divisive. He attracted a devoted following of students, often referred to as "Meldrumites," who embraced his methods rigorously. However, he was also heavily criticized by the established art world, including figures associated with the earlier, nationally celebrated Heidelberg School like Arthur Streeton, and prominent critics such as J.S. MacDonald and Lionel Lindsay, who found his approach mechanical and lacking in imaginative spirit. Despite the controversy, Meldrum's emphasis on careful observation and tonal subtlety profoundly influenced Beckett.

Beckett absorbed Meldrum's core principles regarding the importance of tone and direct observation. However, she did not become a mere imitator. While adhering to the tonal methodology as a foundation, she adapted it to her own sensitive and poetic vision. Her work softened Meldrum's often starker realism, infusing it with a lyrical quality and a focus on atmospheric effects that went beyond purely scientific depiction. Other artists associated with Meldrum included Colin Colahan and Percy Leason, but Beckett's interpretation of Tonalism remained distinctly her own, evolving towards a more suggestive and modern sensibility.

Life in Beaumaris: A Dedicated Vision

In 1919, a significant change occurred in Beckett's life when her family relocated to Beaumaris, a quiet coastal suburb on the edge of Melbourne overlooking Port Phillip Bay. This move proved pivotal for her art. The gentle coastal landscapes, suburban streets, and distinctive weather patterns of the area became the primary subjects of her work for the remainder of her life. Beaumaris provided the backdrop against which she would develop her signature style.

Her life in Beaumaris was marked by domestic responsibility and a somewhat reclusive existence. She remained unmarried and devoted much of her time to caring for her ageing and increasingly frail parents, particularly her mother who reportedly suffered from ill health. This role placed significant constraints on her time and energy, yet her dedication to painting remained resolute. Her routine became legendary: rising before dawn, often around 4 am, she would venture out with a small, portable easel (sometimes even a trolley made from a box cart) to capture the fleeting effects of early morning light along the Beaumaris foreshore or nearby streets.

She often completed paintings en plein air (outdoors) in a single session, working quickly to capture the specific atmospheric conditions before they changed. Sometimes, practicalities dictated she finish works back at home, reportedly using the kitchen table as an impromptu studio. This dedication to capturing specific moments – the mist rising off the sea, the glow of streetlights on a wet road, the soft colours of twilight – became the hallmark of her practice. The Beaumaris environment, with its blend of nature and emerging suburbia, offered endless inspiration for her subtle explorations of light, mood, and place.

Artistic Style: Atmosphere, Light, and Modernity

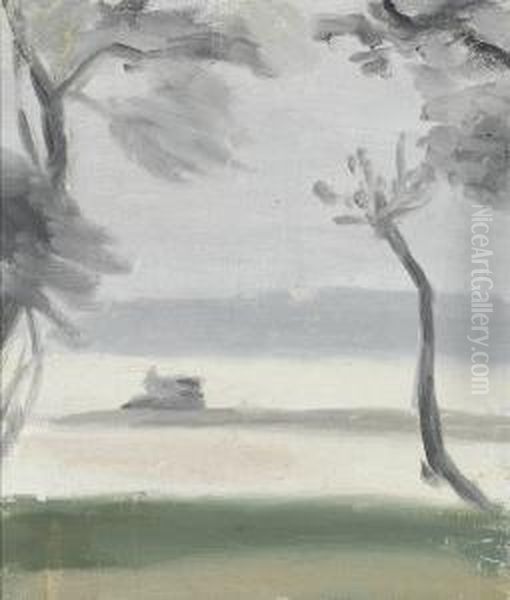

Clarice Beckett's mature artistic style is characterized by its profound sensitivity to atmosphere and light, rendered through a sophisticated understanding of tonal relationships. While grounded in Meldrum's Tonalism, her work transcends its theoretical rigidity, achieving a unique form of lyrical modernism. Her paintings are not dramatic declarations but quiet observations, imbued with a sense of stillness and introspection.

A key feature is her use of a limited, harmonious palette, often dominated by soft greys, muted blues, pinks, ochres, and creams. She masterfully manipulated these tones to suggest form and space, often blurring outlines and allowing objects to merge softly with their surroundings. This technique was particularly effective in depicting fog, mist, rain, dawn, and dusk – conditions where light diffuses and edges soften. Her paintings evoke sensory experiences, capturing the dampness of a wet road or the chill of a foggy morning.

Her compositions are often deceptively simple, focusing on everyday scenes: a deserted beach, a quiet suburban street corner, the glow of car headlights piercing the gloom, telegraph poles receding into the distance, or the solitary form of a bathing box against the sea and sky. Yet, within this simplicity lies a sophisticated formal awareness. She used subtle shifts in tone and carefully balanced geometric elements (like roads, fences, or buildings) to create depth and structure, even as the overall effect remained atmospheric and suggestive. This approach aligns her with modernist tendencies towards simplification and abstraction, where mood and feeling take precedence over detailed description.

Compared to the bright sunlight and distinct forms often celebrated by the earlier Australian Impressionists of the Heidelberg School, like Tom Roberts or Frederick McCubbin, Beckett's work offers a different vision – more intimate, melancholic, and focused on the transitional moments of the day and weather. Her interest in capturing fleeting light effects bears comparison to international Impressionists like Claude Monet, but her tonal focus and subdued palette create a distinctly different, more introspective mood, perhaps closer in spirit to the Tonalism of James McNeill Whistler. Her unique visual language, sometimes described as creating a "misty" or "vibratory" effect, aimed to capture not just the look of a scene, but its essential feeling and the passage of time.

Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as exemplary of Clarice Beckett's unique vision and technical skill. These works encapsulate her recurring themes and stylistic characteristics, demonstrating her mastery of tone and atmosphere.

Wet Night, Brighton (c. 1930): This painting perfectly captures the glistening reflections on a rain-soaked street under the artificial glow of streetlights. Forms are simplified and blurred, conveying the dampness and solitude of a suburban night. The subtle tonal gradations create a sense of depth and moodiness, transforming an ordinary scene into something poetic.

Motor Lights (c. 1929): Here, Beckett tackles the modernity of the automobile age. The painting depicts the glare of headlights cutting through the darkness, reducing the surrounding landscape to near abstraction. It’s a powerful evocation of movement and the ephemeral nature of light in the modern urban environment, rendered with her characteristic tonal subtlety.

Beaumaris Foreshore (c. 1925): This work showcases her ability to capture the soft, diffused light of the coast. The gentle curve of the shoreline, the calm sea, and the hazy sky are rendered in delicate, closely related tones. It conveys a sense of peace and timelessness, typical of her coastal landscapes.

Bathing Box (c. 1929): Often cited as one of her iconic images, this painting features a solitary bathing box against the sea and sky. The composition is simple yet strong, relying on the interplay of horizontal bands of colour and tone. The bathing box becomes a focal point, a small human element within the vastness of nature, rendered with quiet dignity. Castlemaine Art Museum holds a significant version of this subject.

Evening, St Kilda Road (c. 1930): Depicting one of Melbourne's grand boulevards at twilight, this work uses elongated shadows and the soft glow of emerging lights to capture the transition from day to night. The forms of trees and buildings dissolve into the atmospheric haze, creating a dreamlike, evocative scene.

Winter Sundown (c. 1930): This painting demonstrates her skill in capturing the specific colours and light quality of a winter sunset. Muted pinks, oranges, and greys blend softly in the sky and reflect on the landscape below. It’s a quiet meditation on the beauty found in the fading light of a cold day.

These works, among many others, highlight Beckett's consistent focus on the interplay of light, atmosphere, and place, and her ability to elevate mundane subjects into moments of profound visual poetry through her distinctive tonalist approach.

Exhibitions and Contemporary Reception

During her lifetime, Clarice Beckett actively sought to exhibit her work, participating in numerous group shows and holding several solo exhibitions. She showed regularly with the Meldrum group and other societies, such as the Victorian Artists Society and the Twenty Melbourne Painters. She held her first significant solo exhibition at the Melbourne Athenaeum gallery in 1923, followed by others there and at other commercial galleries in subsequent years.

Despite this activity, the critical reception of her work was decidedly mixed, and often lukewarm or even hostile. Her subtle, atmospheric style, with its blurred forms and muted palette, ran counter to the prevailing tastes of the time, which often favoured brighter colours, clearer definition, and more overtly nationalistic or narrative subjects, as seen in the enduring popularity of the Heidelberg School.

Prominent critics like J.S. MacDonald, then director of the National Gallery of Victoria and a staunch defender of more traditional landscape painting, were dismissive. Her work was sometimes criticized for being too "foggy," "monotonous," or lacking in structure and vigour. Some commentary carried gendered undertones, implying her delicate style was merely "feminine" rather than artistically innovative. The perceived influence of Max Meldrum also worked against her in some quarters, as critics opposed to his theories often dismissed his followers wholesale.

However, she did have supporters. Some reviewers recognized the sincerity and sensitivity of her vision, praising her ability to capture elusive effects of light and atmosphere. Max Meldrum himself continued to champion her work. In a rare artist's statement published in conjunction with a 1924 exhibition catalogue, Beckett articulated her aim: "To give a sincere and truthful representation of a portion of the beauty of Nature, and to show the charm of light and shade, which I try to give forth in correct tones so as to give as nearly as possible an exact illusion of reality." This statement underscores her commitment to observed truth, filtered through her unique aesthetic sensibility.

A Life Cut Short and a Legacy Lost

Clarice Beckett's dedicated artistic career was tragically cut short. In 1935, while painting outdoors near Beaumaris during a significant storm, she caught a chill which rapidly developed into pneumonia. She died just a few days later, on July 7, 1935, at the age of only 48. Her premature death silenced a unique voice in Australian art just as her style was reaching its full maturity.

The tragedy was compounded by events following her death. Her father, Joseph Beckett, perhaps grieving and failing to fully appreciate the artistic merit of her extensive output, reportedly destroyed around 200 paintings he considered unfinished or somehow inadequate shortly after her death. This act represented an irretrievable loss to her oeuvre.

The remaining body of work, estimated at around 2,000 paintings and sketches, faced further peril. Lacking proper storage facilities or perhaps recognition of their value, the canvases were moved to an open-sided farm shed in rural Victoria. There, exposed to the elements, dust, and neglect for decades, the vast majority of her life's work suffered irreversible damage from weather, possums, and general decay. This period of neglect nearly consigned Clarice Beckett and her art to complete obscurity. Her sister, Hilda Mangan, played a crucial role in salvaging what was left when the situation was finally realized.

Rediscovery and Re-evaluation

The story of Clarice Beckett's art is one of dramatic loss followed by remarkable rediscovery. For over thirty years after her death, she remained largely forgotten by the mainstream Australian art world. The turning point began in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Art historian and curator Rosalind Hollinrake played a key role in recognizing the significance of the surviving works salvaged by Beckett's sister. Hollinrake organised a small exhibition in 1971 that brought Beckett's paintings back into public view.

This exhibition caught the attention of James Mollison, then the inaugural director of the nascent National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra. Recognizing the unique quality and historical importance of the work, Mollison acquired eight paintings for the national collection directly from that show. This acquisition by a major institution marked a crucial step in Beckett's critical rehabilitation. Following this, Hilda Mangan generously donated more works to the NGA in 1972, which were subsequently conserved and exhibited.

From the 1970s onwards, Beckett's reputation steadily grew. Curators, critics, and art historians began to re-evaluate her contribution, recognizing her as a pioneering modernist whose work offered a distinct and valuable perspective within Australian art history. Her subtle, atmospheric style, once dismissed as foggy or weak, was now appreciated for its sophistication, its poetic sensitivity, and its innovative engagement with Tonalism and modernist principles of simplification and abstraction.

Her rediscovery coincided with a broader reassessment of Australian art history, including a growing interest in the contributions of women artists who had previously been marginalized. Figures like Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith, while perhaps achieving more recognition during their lifetimes than Beckett, also benefited from this renewed focus. Beckett's work began to be contextualized not just within Meldrum's circle, but within the wider currents of early 20th-century modernism, both in Australia (alongside artists like Roy de Maistre and Roland Wakelin exploring colour and abstraction) and internationally, noted for its unique atmospheric qualities.

Exhibitions After Rediscovery

The decades following Clarice Beckett's rediscovery have seen a significant number of exhibitions dedicated to her work, cementing her status as a major figure in Australian art. These shows have allowed audiences across the country and beyond to experience the quiet power of her paintings.

Major survey exhibitions have been crucial. The Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) in Adelaide has been particularly active, mounting significant shows like "Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment" in 2021. This exhibition brought together key works from public and private collections, offering a comprehensive overview of her career and highlighting her focus on capturing fleeting moments. AGSA also presented "Clarice Beckett: See the Light" in 2020, focusing on her masterful depiction of light.

In 2023, the Geelong Gallery in regional Victoria hosted "Clarice Beckett—Atmosphere," described as the first large-scale exhibition of her work in the region since 1999. Its popularity, attracting nearly 27,000 visitors, demonstrated the strong public connection to her art. The exhibition emphasized her ability to evoke mood and sensory experience through her atmospheric landscapes.

The National Gallery of Australia, which played a key role in her initial rediscovery, continues to feature her work. Other institutions, like the Cairns Art Gallery with its "Clarice Beckett: National Collection Paintings" exhibition in 2024, have helped bring her art to wider audiences. Her paintings are also frequently included in thematic exhibitions exploring Australian modernism, landscape painting, and the contributions of women artists, such as touring shows like "Ever Present: First Peoples of Australia" (contextualizing landscape) and "Archie 100" (though primarily portraiture, it reflects broader curatorial interest in the period). These exhibitions have been vital in consolidating her reputation and deepening the understanding of her unique artistic achievement.

Collections and Enduring Influence

Today, Clarice Beckett's work is held in high esteem and is represented in the collections of all major public galleries in Australia, as well as numerous regional galleries and private collections. The National Gallery of Australia (Canberra), the Art Gallery of South Australia (Adelaide), the National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne), the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney), Geelong Gallery, and Castlemaine Art Museum are among the key institutions holding significant examples of her paintings.

Her influence on subsequent generations of Australian artists is perhaps less direct than that of more overtly radical modernists, partly due to the long period of her obscurity. However, her approach to landscape – focusing on intimacy, atmosphere, and the poetics of the everyday – resonates with certain later developments in Australian art. Her dedication to capturing the specific light and mood of the Australian environment, albeit in a much quieter key than the Heidelberg School, prefigures aspects of later landscape painting that moved away from heroic nationalism towards more personal or phenomenological responses to place. Artists exploring subtle light effects or the quietude of suburban or coastal environments might find an echo in Beckett's work, even if not consciously citing her as an influence. Perhaps the atmospheric intensity in some works by William Robinson finds a distant ancestor here.

More broadly, her story serves as a powerful reminder of the contingencies of art history – how talent can be overlooked due to prevailing tastes, gender bias, or simple misfortune. Her eventual recognition underscores the importance of reassessing historical narratives and rediscovering marginalized voices. She stands as a testament to the power of quiet dedication and a singular artistic vision.

Conclusion

Clarice Beckett's journey from a shy girl in rural Victoria to one of Australia's most revered early modernist painters is a compelling narrative of quiet persistence, artistic integrity, and posthumous vindication. Through her unique adaptation of Tonalism, she forged a deeply personal style characterized by atmospheric subtlety, nuanced light, and a poetic sensitivity to the everyday landscapes of coastal Melbourne. Her paintings of foggy mornings, wet streets, and twilight moments capture the ephemeral beauty of the world with a profound sense of stillness and introspection.

Though largely unappreciated during her tragically short life and nearly lost to history due to neglect, her work has been rightfully restored to prominence. Today, Clarice Beckett is celebrated for her innovative approach to painting, her mastery of tone and mood, and her significant contribution to the diverse tapestry of Australian modernism. Her quiet, contemplative canvases continue to resonate, offering viewers moments of serene beauty and reminding us of the extraordinary art that can emerge from a life lived with quiet dedication and a unique way of seeing. She remains a pivotal figure, essential to understanding the development of modern art in Australia.