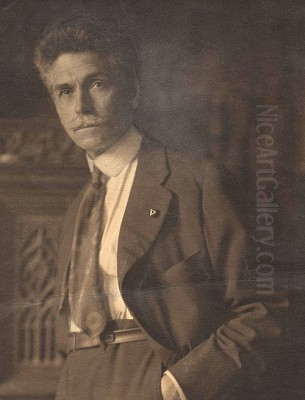

Charles Harold Davis stands as a significant figure in the annals of American landscape painting. Spanning a career that bridged the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Davis navigated the evolving artistic currents of his time, moving from the evocative shadows of Tonalism to the brighter palettes of Impressionism. Renowned particularly for his masterful depictions of cloud-filled skies, he captured the unique atmosphere of the New England landscape, leaving behind a legacy of serene yet dynamic works that continue to resonate with viewers today. His journey from a small Massachusetts town to the art studios of Paris and back to a leadership role in a burgeoning Connecticut art colony is a testament to his dedication and evolving vision.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Amesbury, Massachusetts, in 1856, Charles Harold Davis displayed an early inclination towards the arts. While detailed accounts of his earliest years are sparse, it's known that his artistic sensibilities were nurtured from a young age. An interesting, though perhaps apocryphal, anecdote suggests a period spent working in a carriage factory, a practical occupation far removed from the painter's studio. Whether this experience provided an unexpected grounding or simply a contrast that fueled his artistic desires, Davis ultimately committed to a life in art.

His formal training began not in the ateliers of Europe, but closer to home at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This institution was becoming a vital center for art education in America. During his time there, likely in the late 1870s, he studied under the German-born painter Otto Grundmann. Grundmann, who had studied in Antwerp and Düsseldorf, brought a European academic sensibility to Boston, emphasizing solid draftsmanship and traditional techniques. This foundational training provided Davis with the technical skills necessary for his future explorations in landscape painting.

The Parisian Experience

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Davis recognized the necessity of experiencing European art firsthand, particularly the vibrant art scene of Paris. In 1880, he embarked for France, immersing himself in the academic traditions and the burgeoning modern movements that defined the era. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school known for attracting international students and offering a more liberal alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts.

At the Académie Julian, Davis studied under the guidance of prominent academic painters Jules Joseph Lefebvre and Gustave Boulanger. Both were highly respected figures within the French art establishment, known for their historical and allegorical paintings, as well as their portraiture. They instilled in their students a rigorous approach to figure drawing and composition, principles that would subtly underpin Davis's later landscape work. While his ultimate path diverged from the historical subjects favored by his teachers, the discipline learned under their tutelage was invaluable.

However, it was outside the formal structure of the academy that Davis found influences perhaps more aligned with his burgeoning interest in landscape. He spent considerable time in the French countryside, particularly in the vicinity of Barbizon, near the Forest of Fontainebleau. This area had given its name to the Barbizon School of painters decades earlier. Artists like Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot had pioneered a form of naturalistic landscape painting, working directly from nature and emphasizing mood and atmosphere over precise topographical detail. Davis absorbed the spirit of Barbizon, evident in the tonal harmonies and poetic sensibility of his early French landscapes. He was particularly drawn to the work of Millet, whose depictions of rural life and landscape resonated with a quiet dignity.

During his decade abroad, Davis began to achieve recognition. He exhibited works at the Paris Salon, the official, highly competitive annual exhibition. Receiving an honorable mention at the Salon, likely in 1887, was a significant early validation of his talent on an international stage. His time in France was crucial, exposing him not only to academic rigor and the legacy of the Barbizon school but also placing him in proximity to the developing Impressionist movement, whose principles of light and color would profoundly impact his later work. He also encountered the realism of artists like Gustave Courbet, further broadening his artistic horizons.

Return to America and the Mystic Colony

After a formative decade in France, Charles Harold Davis returned to the United States in 1890. He chose not to settle in a major urban art center like New York or Boston, but instead sought the tranquility and scenic beauty of rural New England. He established his home and studio in Mystic, Connecticut, a coastal village known for its maritime history and picturesque surroundings. This decision proved pivotal for both his art and his role within the American art community.

The Connecticut landscape offered Davis a new, yet familiar, source of inspiration. The rolling hills, meandering waterways, and expansive skies of the region became the primary subjects of his work for the remainder of his career. He found in Mystic a place conducive to the quiet contemplation of nature that his painting required. He quickly became a central figure among the artists who were increasingly drawn to the area, attracted by its natural beauty and relative seclusion.

Recognizing the potential for a supportive artistic community, Davis played an instrumental role in founding the Mystic Art Association in 1913 (now the Mystic Museum of Art). He served as its first president, helping to establish an organization that provided exhibition opportunities and fostered camaraderie among local artists. This initiative cemented Mystic's reputation as an important art colony, distinct from but contemporary with others like Old Lyme, also in Connecticut, which was becoming known for American Impressionism through artists like Childe Hassam and Willard Metcalf. Davis's leadership helped shape the character of the Mystic art scene, encouraging a focus on landscape painting and fostering a connection between artists and the local environment. His home became a gathering place, and his influence extended beyond his own canvases to the development of a regional artistic identity.

Evolution of Style: From Tonalism to Impressionism

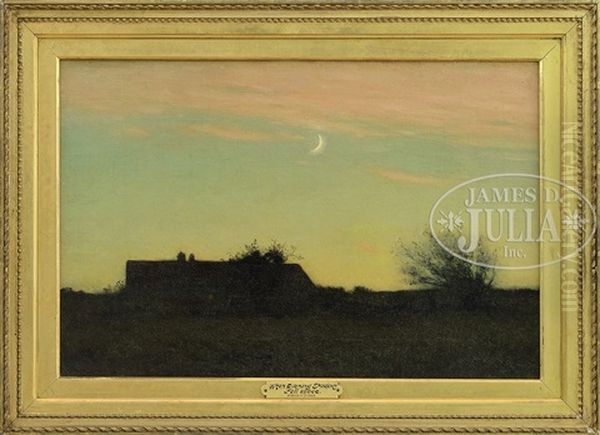

Charles Harold Davis's artistic journey is marked by a distinct evolution in style, reflecting both his European training and his response to the changing artistic landscape in America. His early work, heavily influenced by his time near Barbizon and the paintings of artists like Millet and Corot, aligns closely with the Tonalist movement. Tonalism, which flourished in America in the late 19th century, was characterized by its emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and subtle harmonies of color. Tonalist painters often favored twilight or hazy conditions, using a limited palette of muted greens, browns, blues, and grays to evoke poetic feeling rather than literal description.

Davis's early landscapes from this period often feature soft, diffused light, simplified forms, and a quiet, introspective quality. Works like Late Afternoon (held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art) exemplify this phase, showcasing his ability to capture the gentle melancholy of the day's end through subtle gradations of tone and a focus on the overall atmospheric effect. He shared this sensibility with other American Tonalists such as George Inness and James McNeill Whistler, who similarly sought to convey the subjective experience of nature.

However, as the twentieth century dawned, Davis's style began to shift. While retaining his fundamental interest in landscape and atmosphere, he increasingly embraced the principles of Impressionism. This transition likely stemmed from his earlier exposure to French Impressionism and the growing prominence of American Impressionists like Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and John Henry Twachtman, many of whom were also working in Connecticut. His palette brightened considerably, incorporating purer, more vibrant colors. His brushwork became looser and more visible, used to capture the fleeting effects of light and air.

This later phase, while clearly Impressionistic, retained a unique character. Davis did not fully dissolve form in light in the manner of Claude Monet, nor did he typically focus on the urban or leisure scenes favored by some Impressionists. Instead, he adapted Impressionist techniques to his established interest in the rural landscape and, most notably, the sky. His focus shifted from the muted light of dusk to the clearer light of day, exploring the interplay of sunlight and shadow across the Connecticut hills and fields. This evolution demonstrates his ability to absorb contemporary trends while remaining true to his personal vision.

The Signature Sky: Master of Cloudscapes

While adept at rendering the terrestrial elements of the landscape, Charles Harold Davis became particularly renowned for his depictions of the sky. Clouds were not mere backdrops in his paintings; they were often the principal subject, imbued with personality and dramatic force. His fascination with celestial phenomena led to the development of what critics and admirers often referred to as the "Davis sky"—a recognizable signature element of his mature work.

These skies are typically characterized by large, billowing cumulus clouds, sculpted by light and shadow, set against expanses of warm, luminous blue. Davis masterfully captured the sense of volume, movement, and ephemeral beauty of cloud formations. He rendered them with a combination of observational accuracy and artistic interpretation, suggesting the ever-changing drama of the atmosphere. His brushwork in these areas could range from broad, sweeping strokes defining the mass of the clouds to more delicate touches suggesting wisps and edges catching the light.

Works such as The Clearing (circa 1915) and other paintings titled Clouds and Hills prominently feature these dynamic skies dominating the composition. The land below often serves as a grounding element, a darker, simpler band anchoring the complex aerial display above. Through his focus on the sky, Davis explored themes of nature's grandeur, the passage of time, and the transcendent power of light. His cloudscapes possess a romantic sensibility, elevating the everyday spectacle of the weather into a subject of profound beauty. This specialization distinguished him from many of his contemporaries and cemented his reputation as a master of atmospheric effects. His ability to convey the weight, texture, and luminosity of clouds remains one of the most celebrated aspects of his oeuvre.

Recognition and Exhibitions

Throughout his long career, Charles Harold Davis achieved significant recognition both nationally and internationally. His consistent participation in major exhibitions and the numerous awards he received attest to his standing in the art world of his time. Following his early success at the Paris Salon, he continued to submit works to important juried shows upon his return to the United States.

He became a regular exhibitor at prestigious institutions such as the National Academy of Design in New York (where he was elected an Associate in 1901 and a full Academician in 1906), the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and the Art Institute of Chicago. His work was consistently well-received, earning him medals and prizes that solidified his reputation. Notable awards include a silver medal at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo (1901), a silver medal at the Universal Exposition (World's Fair) in St. Louis (1904), and the prestigious Gold Medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco (1915).

Davis's inclusion in the landmark International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show, in New York City in 1913, is particularly noteworthy. While the Armory Show is famous for introducing European avant-garde art (like Cubism and Fauvism) to a shocked American public, it also included works by many established American artists. Davis's participation indicates his relevance within the contemporary American art scene, even as newer, more radical styles were emerging. His landscape paintings, though representing a more traditional approach compared to the European modernists, held their own within this diverse and transformative exhibition. His work was handled by prominent dealers, such as Macbeth Gallery in New York, ensuring its visibility to collectors and critics.

The consistent accolades and exhibition record demonstrate the high regard in which Davis was held by his peers and the art establishment. His paintings entered major museum collections during his lifetime, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (now dispersed, with some works potentially at the National Gallery of Art), the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, among others. This institutional recognition further cemented his place as a leading American landscape painter.

Association with Contemporaries

Charles Harold Davis did not work in isolation. His career unfolded during a dynamic period in American art, and he was connected, both stylistically and personally, to many of the key figures of his time. His early Tonalist phase placed him in the company of George Inness and Alexander Wyant, artists who similarly sought to capture the poetic moods of nature. While perhaps less mystical than Inness, Davis shared the Tonalist emphasis on atmosphere and subjective feeling.

As his style evolved towards Impressionism, he became associated with the leading American Impressionists. Although based in Mystic rather than the Cos Cob or Old Lyme colonies where artists like John Henry Twachtman, J. Alden Weir, and Childe Hassam congregated, Davis shared their interest in capturing the effects of light and color in the New England landscape. His work can be compared to theirs, though his focus often remained more on the structure of the land and the drama of the sky, perhaps retaining a stronger link to his Barbizon roots than some of his contemporaries like Hassam, who more fully embraced Impressionist broken color and scenes of modern life. He was also contemporary with Theodore Robinson, who played a key role in transmitting French Impressionist ideas back to America, and William Merritt Chase, a hugely influential painter and teacher.

Within the Mystic art colony that he helped establish, Davis was a central figure. He interacted with and influenced other artists drawn to the area, such as the Tonalist-influenced painter Henry Ward Ranger (though Ranger is more strongly associated with Old Lyme) and later figures like Robert Brackman and George Albert Thompson. His leadership in the Mystic Art Association fostered a sense of community and shared purpose among these artists. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some figures in American art history, Davis occupied a respected position, bridging the gap between the established traditions of the 19th century and the newer approaches of the early 20th century. His work provides a valuable perspective on the particular way American artists adapted and personalized international styles like Tonalism and Impressionism, grounding them in the specific character of the American landscape. He stands alongside figures like Winslow Homer as a profound interpreter of the American scene, though Homer's focus often lay more on the power of the sea and the human figure within nature.

Later Years and Legacy

Charles Harold Davis continued to paint actively throughout the later decades of his life, remaining based in Mystic, Connecticut. His commitment to landscape painting, particularly the scenery of his adopted state, never wavered. While the art world saw the rise of Modernism, Regionalism, and other movements, Davis largely maintained the Impressionist-inflected style he had developed, focusing on the enduring beauty of nature and the atmospheric effects of light and sky. He remained a respected elder statesman in the Connecticut art scene until his death in Mystic in 1933.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he is celebrated for his technical skill, his sensitive response to the New England landscape, and especially his mastery of cloudscapes. The "Davis sky" remains his most distinctive contribution, a testament to his dedicated observation and artistic interpretation of atmospheric phenomena. His works are admired for their serene beauty, their balance between naturalism and poetic feeling, and their skillful handling of light and color.

As a key figure in the Mystic art colony and the founder of the Mystic Art Association, Davis made a lasting contribution to the cultural life of Connecticut and the broader American art community. He helped create an environment where artists could thrive, exhibit their work, and engage with the local landscape. The Mystic Museum of Art stands today as a direct result of his initiative and leadership.

His work continues to be held in high regard and is represented in numerous important public and private collections across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the New Britain Museum of American Art, and the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Exhibitions featuring his work continue to be organized, reaffirming his position as a significant American landscape painter whose art transcends his own time.

Conclusion

Charles Harold Davis carved a distinct and respected path through the American art world. From his foundational training in Boston and Paris to his mature years as a leading figure in the Mystic art colony, he dedicated himself to capturing the essence of the landscape. His artistic evolution from the moody depths of Tonalism to the luminous vibrancy of Impressionism reflects the broader shifts in American art, yet his focus on the dramatic beauty of the sky gave his work a unique and enduring signature. More than just a painter of pleasant scenes, Davis was a poet of atmosphere, light, and the ever-changing New England heavens. His contribution lies not only in his beautiful canvases but also in his role fostering an artistic community, leaving a legacy that continues to enrich our appreciation of American landscape painting.