Philippe de Champaigne stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of 17th-century French art. Born in Brussels but spending the vast majority of his prolific career in Paris, he navigated the complex currents of the Baroque era, ultimately forging a distinctive style that blended Flemish realism with French classicism and profound spiritual depth. His legacy rests not only on his masterful portraits of the era's leading figures but also on his deeply felt religious paintings, many influenced by the austere Jansenist movement.

From Brussels to Paris: Early Life and Training

Philippe de Champaigne entered the world in Brussels in 1602, into a family of modest means. The Southern Netherlands, then under Spanish rule, was a vibrant artistic center dominated by the influence of Peter Paul Rubens. Champaigne's initial artistic education took place in his native city. He first studied under the landscape painter Jacques Fouquières, an artist known for his detailed depictions of nature, which may have instilled in the young Champaigne an appreciation for careful observation.

His training continued with instruction in portraiture, reportedly under Jean Bouillon, though less is known about this master. These formative years in Brussels exposed him to the rich textures, detailed naturalism, and often robust characterizations typical of Flemish painting. However, the lure of Paris, the burgeoning artistic and political capital of France under Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu, proved irresistible.

In 1621, at the age of nineteen, Champaigne made the decisive move to Paris. This relocation marked the true beginning of his independent artistic journey. The French capital offered new opportunities, different stylistic influences, and the chance to associate with other ambitious young artists, setting the stage for his rise to prominence.

Parisian Beginnings and Formative Collaborations

Upon arriving in Paris, Champaigne quickly sought opportunities to establish himself. A significant early connection was formed with Nicolas Poussin, another non-native artist (from Normandy) who would become one of the defining figures of French Classicism. The two young painters found themselves working together, alongside other artists, on the decorations for the Palais du Luxembourg, the Parisian residence commissioned by Queen Marie de' Medici.

This project, overseen by established masters, provided invaluable experience and exposure. Champaigne and Poussin reportedly shared lodgings for a time and studied together at the Collège de Laon, deepening their artistic dialogue. While their paths would eventually diverge stylistically – Poussin embracing a more rigorously classical and historical mode, Champaigne retaining a stronger connection to Northern European realism – this early association was undoubtedly formative.

During this period, Champaigne also likely absorbed the influence of Simon Vouet, who had returned from Italy in 1627 and quickly became the leading painter in Paris, popularizing a lighter, more decorative Italian Baroque style. Champaigne worked briefly under the direction of Nicolas Duchesne, whose daughter he would later marry. His talent was evident, and he began to attract attention for his skill and diligence.

Rise to Prominence: Court Painter and Official Commissions

Champaigne's career trajectory accelerated significantly following the death of his brief employer, Nicolas Duchesne, in 1628. He married Duchesne's daughter, Charlotte, in the same year. More importantly, his talents had caught the eye of the Queen Mother, Marie de' Medici. She appointed him as her official painter (peintre de la reine mère), granting him a pension and lodgings in the Luxembourg Palace. This royal patronage was a crucial step, elevating his status considerably.

Soon after, Champaigne came into the orbit of Cardinal Richelieu, the powerful chief minister of France. Richelieu became one of Champaigne's most important patrons, commissioning numerous works, including portraits, religious paintings for his chapel at the Sorbonne, and decorations for his Palais-Cardinal (now the Palais-Royal). Champaigne's famous full-length portrait of Richelieu, as well as the innovative Triple Portrait of Cardinal Richelieu (likely created as a study for the sculptor Francesco Mochi), cemented his reputation as a portraitist of the highest rank.

His success continued under King Louis XIII, who also employed him extensively. Champaigne painted multiple portraits of the King, often depicting him in solemn, official poses that conveyed regal authority and piety, such as Louis XIII Crowned by Victory. These commissions placed Champaigne at the very center of French political and cultural life, making him the preferred painter for the kingdom's elite.

Artistic Style: A Unique Blend of Realism and Restraint

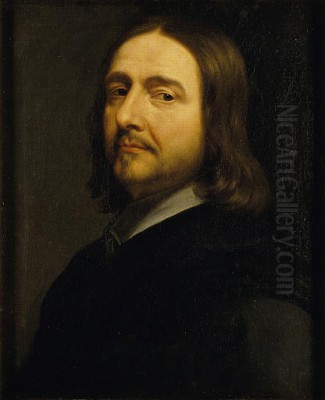

Philippe de Champaigne's style is often characterized as a unique synthesis of Northern European, specifically Flemish, realism and French classical restraint. Unlike the more exuberant and dynamic High Baroque of Rubens or Italian masters like Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Champaigne's work generally exhibits a greater sobriety, gravity, and psychological focus.

From his Flemish roots, he retained a meticulous attention to detail, a mastery of rendering textures (fabric, fur, metal), and a commitment to capturing a truthful likeness. His portraits are rarely idealized in the conventional sense; instead, they convey a sense of direct, unvarnished observation. Wrinkles, imperfections, and the specific cast of a sitter's features are rendered with precision.

However, this realism is tempered by a French sense of order, balance, and psychological depth. His compositions are typically stable and clear, often employing simple backgrounds or architectural settings that avoid distraction. He excelled at conveying the inner life and character of his sitters through subtle expressions, posture, and especially the intensity of their gaze. This psychological penetration is a hallmark of his portraiture.

His use of color evolved. While some early works show richer palettes, his mature style, particularly under the influence of Jansenism, often favored more somber tones, with blacks, grays, and deep reds dominating, punctuated by areas of white or specific detail colors. His handling of light is often clear and direct, modeling forms effectively but generally avoiding the dramatic chiaroscuro found in artists like Caravaggio or Georges de La Tour.

The Académie Royale and Institutional Role

Champaigne played a significant role in the formalization of the arts in France. In 1648, he was among the founding members of the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture). This institution, established under the patronage of the monarchy, aimed to regulate and elevate the status of artists, provide structured training, and promote a French national style based on classical principles.

His involvement was not merely nominal. He actively participated in the Academy's activities and held important positions. In 1655, he was appointed as a Professor, responsible for delivering lectures and instruction to students. His lectures often emphasized drawing, anatomical accuracy, and the importance of studying nature and the Old Masters, reflecting his own artistic principles.

Later, he served as Rector of the Academy, further solidifying his position as a respected elder statesman of the French art world. His presence lent considerable weight and seriousness to the institution. While Charles Le Brun eventually became the dominant figure at the Academy, wielding immense influence under Louis XIV, Champaigne remained a highly regarded member, representing a slightly different, perhaps more austere and less overtly decorative, artistic sensibility compared to Le Brun's grand manner. His participation helped shape the academic tradition that would dominate French art for centuries.

Religious Conviction and the Influence of Jansenism

Religion was a central theme throughout Champaigne's life and work, but his approach deepened and shifted significantly, particularly from the 1640s onwards, due to his association with Jansenism. Jansenism was a Catholic theological movement emphasizing original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. It advocated a life of strict piety, austerity, and detachment from worldly concerns. Its main center in France was the Port-Royal Abbey near Paris.

Champaigne developed close ties with the figures associated with Port-Royal, including prominent theologians and intellectuals like Antoine Arnauld and Blaise Pascal (though Pascal was more a sympathizer than a formal member). He painted portraits of many key Jansenist figures, such as Robert Arnauld d'Andilly and the Abbé de Saint-Cyran. These portraits are often characterized by their stark simplicity, psychological intensity, and lack of flattery, reflecting the movement's sober ethos.

The most profound impact of Jansenism on Champaigne's art is seen in his religious paintings from this period. His style became increasingly austere, compositions simplified, and emotional expression more internalized and restrained. The focus shifted towards quiet contemplation, spiritual gravity, and the solemn mysteries of faith, moving away from the more theatrical elements of the mainstream Baroque.

Masterpieces of Faith and Family: The Ex-Voto

Perhaps the most famous and personally significant work related to Champaigne's Jansenist faith is the painting known as the Ex-Voto de 1662, now housed in the Louvre. Its full title is Mother Catherine-Agnès Arnauld and Sister Catherine de Sainte Suzanne Champaigne. Sister Catherine de Sainte Suzanne was the artist's own daughter, a nun at the Port-Royal convent.

The painting commemorates what was considered a miraculous event. Champaigne's daughter had been suffering from paralysis for over a year. After a novena (a nine-day period of prayer) was offered at the convent, she suddenly regained her ability to walk. The painting depicts Sister Catherine lying in bed, seemingly still unwell but peaceful, while the prioress, Mother Agnès Arnauld, kneels beside her in prayer. A ray of light illuminates the scene, symbolizing divine intervention.

The work is extraordinary for its stark simplicity, emotional restraint, and profound sense of quiet faith. It avoids any dramatic gestures or overt displays of miracle. Instead, it conveys deep gratitude and piety through the intense, focused gazes of the two nuns and the austere setting. The meticulous rendering of the figures and their surroundings grounds the spiritual event in tangible reality. It remains one of the most powerful expressions of Jansenist spirituality in art and a deeply personal testament from the artist.

Other significant religious works demonstrate his evolving style. His depictions of The Last Supper, The Dead Christ Laid on His Shroud, and scenes from the lives of saints often share this combination of realistic detail and solemn, introspective mood. He treated these sacred subjects with immense seriousness and a focus on their theological and emotional weight.

Later Career and Portraits

Even as his style grew more austere under Jansenist influence, Champaigne remained highly sought after as a portraitist throughout his later career. He continued to paint members of the court, the clergy, the judiciary, and the intellectual elite of Paris. These later portraits often possess a remarkable psychological acuity, capturing the sitter's personality and social standing with clarity and dignity.

Notable examples from this period include his portraits of figures like Omer Talon, a prominent magistrate known for his integrity, and Robert Arnauld d'Andilly, a key figure in the Port-Royal circle. These works often feature dark clothing and plain backgrounds, focusing attention entirely on the sitter's face and expression. The meticulous rendering of features and the direct, often penetrating gaze create a powerful sense of presence.

His ability to convey both the external likeness and the inner character of his subjects remained undiminished. Even within the constraints of official portraiture, he managed to imbue his subjects with a sense of individuality and gravitas. His consistent quality and profound seriousness set him apart from many contemporaries.

Workshop, Collaborators, and Engravers

Like most successful artists of his time, Philippe de Champaigne maintained an active workshop to assist him with the numerous commissions he received. His most important collaborator was undoubtedly his nephew, Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne (1631-1681). Jean-Baptiste trained under his uncle from a young age and became a capable painter in his own right, often working in a style very close to Philippe's. He assisted on large projects and sometimes completed replicas or variations of his uncle's compositions.

Other assistants likely passed through the workshop over the years, helping with backgrounds, drapery, or preparatory work. The exact extent of workshop participation in many works is a subject of ongoing art historical discussion, but the guiding hand and distinct style of Philippe de Champaigne remain evident in his major pieces.

Champaigne also collaborated, in a sense, with engravers who translated his paintings into prints, making his compositions accessible to a wider audience. Prominent engravers like Jean Morin and Robert Nanteuil created high-quality prints after his portraits and religious scenes. These prints helped to disseminate his work and solidify his reputation throughout France and beyond. His friendship with the Antwerp landscape painter Mathias van Plattenberg (sometimes referred to as 'Puytten' or 'Plattenborch') is also documented, evidenced by a portrait Champaigne painted of him in 1654.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Philippe de Champaigne worked during a rich and complex period in French art. His career overlapped with several major figures whose styles offered points of comparison and contrast. His early association with Nicolas Poussin highlights two different responses to the artistic challenges of the era – Poussin's rigorous classicism versus Champaigne's blend of realism and restraint.

Simon Vouet represented the more decorative, Italianate Baroque influence that was popular in the earlier part of Champaigne's career. Charles Le Brun emerged as the dominant force in the latter half, orchestrating the grand artistic projects of Louis XIV at Versailles with a powerful, often allegorical, and highly organized style that defined the official art of the Grand Siècle. Champaigne's more sober and introspective approach offered an alternative to Le Brun's grandeur.

Other notable contemporaries included Laurent de La Hyre and Eustache Le Sueur, fellow founding members of the Academy who developed their own classically influenced styles, often with a gentle lyricism distinct from Champaigne's severity. Landscape painters like Claude Lorrain perfected idealized classical landscapes, while artists like the brothers Le Nain (Antoine, Louis, Mathieu) focused on genre scenes of peasant life with a remarkable dignity, and Georges de La Tour created dramatically lit nocturnal scenes in relative isolation in Lorraine. Champaigne navigated this diverse landscape, maintaining his unique artistic identity influenced by, but distinct from, Flemish masters like Rubens and Anthony van Dyck.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Philippe de Champaigne died in Paris in 1674, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant artistic legacy. He is remembered as one of the leading painters of the French Baroque era, particularly renowned for his portraiture. His ability to capture both the physical likeness and the psychological depth of his sitters set a high standard for the genre in France.

His religious paintings, especially those influenced by Jansenism, offer a profound counterpoint to the more exuberant religious art of the period. Their austerity, sincerity, and quiet intensity continue to resonate with viewers. The Ex-Voto de 1662 remains an iconic work of French painting, admired for both its artistic mastery and its deep spiritual feeling.

Through his role in the Académie Royale, he contributed to the institutional framework of French art and influenced subsequent generations of artists trained within the academic system. While his style might have seemed somewhat conservative compared to the later Rococo frivolity exemplified by artists like François Boucher or Jean-Honoré Fragonard, his emphasis on truthful observation, solid composition, and psychological insight ensured his enduring reputation.

He successfully bridged the gap between the rich realism of his Flemish heritage and the classical ideals increasingly favored in France, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and artistically compelling. His paintings provide invaluable visual documents of the key figures and the spiritual climate of 17th-century France.

Scholarly Attention and Exhibitions

The importance of Philippe de Champaigne has long been recognized by art historians. The foundational work for modern scholarship is the multi-volume catalogue raisonné compiled by Bernard Dorival, published in the mid-20th century and supplemented later. This comprehensive study meticulously documents Champaigne's life, oeuvre, and related works.

Numerous articles and books have further explored specific aspects of his career, including his relationship with Jansenism (e.g., works by Gail Feigenbaum), his portraiture techniques, and his place within the broader context of European Baroque art. Scholars like Alain Tapié and Nicolas Sainte Fare Garnot have continued to shed light on his work.

Major exhibitions have periodically brought Champaigne's art to public attention. A significant retrospective was held in 1952 at the Orangerie in Paris. More recently, a large-scale exhibition titled "Philippe de Champaigne, 1602-1674: Entre politique et dévotion" was organized and shown in Lille (Palais des Beaux-Arts) and Geneva (Musée Rath) in 2007-2008. This exhibition, curated by Tapié and Sainte Fare Garnot, brought together many of his most important paintings, drawings, and related works, including pieces by his nephew Jean-Baptiste, offering a comprehensive reassessment of his career for a new generation. His works remain key holdings in major museums worldwide, particularly the Louvre in Paris.

Conclusion: A Master of Observation and Soul

Philippe de Champaigne remains a towering figure in French art history. His journey from Brussels to the heart of the Parisian art world resulted in a unique artistic vision that combined the meticulous realism of the North with the structure and psychological depth valued in French classicism. As the premier portraitist of the French elite during the reigns of Louis XIII and the early years of Louis XIV, he captured the faces of power and intellect with unparalleled clarity and insight. Simultaneously, his deep religious convictions, profoundly shaped by Jansenism, led him to create some of the most moving and spiritually intense paintings of the era. A founder of the Academy, a master craftsman, and an artist of profound integrity, Philippe de Champaigne left an indelible mark on the art of the Grand Siècle.