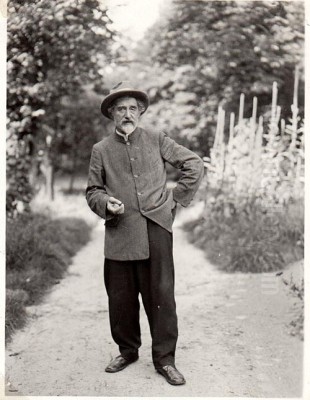

Constant Montald stands as a pivotal figure in the rich tapestry of Belgian art, an artist whose career spanned the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Ghent, Belgium, on December 4, 1862, and passing away on March 5, 1944, Montald's life and work are intrinsically linked to the Symbolist movement, yet his contributions extended far beyond a single stylistic classification. He was a painter of profound depth, a creator of monumental murals, a skilled sculptor, and an influential teacher, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of his nation and beyond. His journey through the art world reflects a dedication to an art that was both aesthetically pleasing and intellectually stimulating, often imbued with allegorical meaning and a quest for the ideal.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Constant Montald's artistic journey began in his birthplace of Ghent, a city with a venerable artistic heritage. He enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, an institution that provided him with a solid foundation in academic artistic principles. This early training was crucial, instilling in him the technical proficiency that would later allow him to explore more personal and innovative artistic expressions. Like many ambitious artists of his era, Montald recognized the importance of Paris as the epicenter of the art world.

He ventured to the French capital to further his studies and immerse himself in its vibrant artistic milieu. In Paris, he briefly shared a studio and learning environment with Henri Privat-Livemont, another Belgian artist who would become known for his Art Nouveau posters and decorative work. This period in Paris exposed Montald to a confluence of artistic currents, from lingering academic traditions to the burgeoning avant-garde movements that were challenging established norms.

A significant turning point in Montald's early career came in 1886 when he was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome. This Belgian version of the prize, akin to its French counterpart, was a highly coveted honor that provided laureates with the means to travel and study, typically in Italy. For Montald, this award was not merely a recognition of his talent but a gateway to further artistic development. His travels, which also took him to Egypt, broadened his horizons and undoubtedly enriched his visual vocabulary and thematic concerns, allowing him to absorb classical traditions and diverse cultural aesthetics.

The Embrace of Symbolism

While Montald's early work may have shown inclinations towards realism, his artistic trajectory increasingly veered towards Symbolism. This late 19th-century movement, which flourished across Europe, sought to express ideas, emotions, and spiritual values through suggestive imagery and metaphorical narratives, rather than depicting the objective reality favored by Realism and Impressionism. Belgian Symbolism, in particular, developed a distinctive character, often marked by a sense of mystery, introspection, and a fascination with the dreamlike and the esoteric. Artists like Fernand Khnopff, Jean Delville, and Félicien Rops were prominent figures in this Belgian milieu.

Montald became one of the foremost proponents of Symbolism in Belgium. His paintings began to feature allegorical figures, ethereal landscapes, and a palette that often emphasized evocative color harmonies, particularly blues and golds, which became something of a signature. He was drawn to grand themes: the human condition, the pursuit of ideals, the interplay of nature and spirit, and the mysteries of existence. His works aimed to transcend the mundane, inviting viewers into a realm of contemplation and poetic reverie.

His commitment to Symbolist ideals was also evident in his association with like-minded artists and writers. He cultivated a significant friendship with the poet Emile Verhaeren, a leading voice in Belgian literature and a fervent supporter of modern art. Together, they shared an interest in an art that could engage the public sphere. Montald also counted the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig among his acquaintances, indicating his integration into a broader European intellectual and artistic network.

Monumental Aspirations: Murals and Decorative Arts

Constant Montald is perhaps best remembered for his ambitious large-scale murals and decorative paintings, which adorned public and private spaces. He believed in the power of art to elevate public life and saw monumental art as a means to achieve this. His approach to mural painting was significantly influenced by the French master Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose work was admired for its serene classicism, simplified forms, and harmonious integration with architecture. Like Puvis, Montald often aimed for a sense of timelessness and universal significance in his murals.

One of his most notable mural projects was "The Human Struggle" (La Lutte humaine). Originally conceived for the Justice Palace (Palais de Justice) in Brussels, this monumental work eventually found its home in the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent. Such large-scale compositions allowed Montald to explore complex allegorical themes on an epic scale, using the human form to convey abstract concepts and emotional states.

His decorative talents were further showcased in the entrance hall of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels. Here, he created two magnificent works, "The Ideal Boat" (Le Bateau de l’Idéal, also sometimes referred to as La Barque de l'Idéal) and "The Fountain of Inspiration" (La Fontaine de l’Inspiration). These pieces, characterized by their grand scale and rich, symbolic imagery, exemplify his vision of an art that is both decorative and deeply meaningful. The use of gold and luminous blues in these works creates an almost otherworldly atmosphere, perfectly aligning with Symbolist aesthetics.

Montald's involvement in decorative arts extended to sgraffito work, a technique involving scratching through a layer of plaster to reveal a different colored layer underneath. Between 1897 and 1899, he created sgraffito designs for the facade of the Royal Dutch Theatre (Koninklijke Nederlandse Schouwburg) in Ghent, a building designed by the architect Edmond De Vigne. This project demonstrated his versatility and his commitment to integrating art with architecture.

Beyond the Canvas: Sculpture and Architecture

While primarily known as a painter, Montald's artistic endeavors were not confined to two dimensions. He also engaged with sculpture, further exploring the human form and symbolic expression in three-dimensional space. Though perhaps less central to his oeuvre than his paintings and murals, his sculptural work reflects the same thematic concerns and aesthetic sensibilities.

His interest in the integration of arts led him to architecture. In 1909, Montald designed and built a villa for himself in Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, a suburb of Brussels. This Villa Montald (sometimes referred to as Villa Montald) became more than just a home; it was an artistic statement and a gathering place for artists and writers, including his friend Emile Verhaeren. The villa itself was conceived as a harmonious environment, and Montald adorned it with his own creations, including mosaics, further blurring the lines between fine art, decorative art, and architecture. This holistic approach was characteristic of the era, echoing the ideals of movements like Art Nouveau, where artists like Victor Horta were creating "total works of art."

A Teacher of Influence

Constant Montald's impact on Belgian art was amplified through his long and distinguished teaching career. He served as a professor at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1896 for several decades, until 1932. In this role, he shaped the development of several generations of Belgian artists. His teaching was rooted in a strong understanding of academic principles, but his own Symbolist leanings likely encouraged students to explore personal vision and expressive content.

Among his most famous pupils was René Magritte, who would later become a world-renowned Surrealist painter. While Magritte's artistic path ultimately diverged significantly from Montald's Symbolism, the foundational training received at the Academy under professors like Montald was part of his formative experience. Magritte himself expressed a certain ambivalence towards his academic training, yet the environment undoubtedly exposed him to various artistic ideas and technical skills.

Other notable artists who studied under Montald included Paul Delvaux, another key figure in Belgian Surrealism, known for his dreamlike paintings of nudes and classical architecture. The sculptor Armand Bonnetain also benefited from Montald's tutelage. The fact that artists who went on to explore vastly different styles, such as Surrealism, passed through his studio speaks to the breadth of influence an academic institution and its professors could have, even if students later rebelled against or moved beyond those initial teachings. Montald's dedication to teaching ensured that his influence extended far beyond his own creative output.

Artistic Collaborations and Societies

Montald was an active participant in the artistic life of his time, not only through his personal creations and teaching but also through his involvement in artistic societies. He was a co-founder, alongside Jean Delville, Émile Fabry, and others, of "L’Art Monumental" (Monumental Art) in 1920. This group, promoted by Verhaeren, aimed to encourage the creation of large-scale decorative works for public buildings, believing in art's social role and its capacity to beautify civic spaces. This initiative reflected Montald's enduring commitment to monumental art and its integration into the fabric of society.

Earlier, his friendship with Emile Verhaeren also led to collaborations and shared ideals. They were involved in initiatives that sought to bridge the gap between art and the public, reflecting a common desire to see art play a more significant role in everyday life. The "Société Nature Art," which he co-founded, also aimed to promote public art projects, emphasizing themes drawn from nature and idealized visions.

War, Later Career, and Enduring Themes

The outbreak of World War I inevitably impacted Montald's artistic production. The conditions of war and occupation made it difficult, if not impossible, to undertake large-scale mural commissions. During this period, he turned his attention to smaller-scale works, including landscapes. These pieces, while perhaps less grand in ambition than his murals, still bore the hallmarks of his style: a sensitivity to atmosphere, an evocative use of color, and a tendency towards idealized or symbolic interpretations of nature.

Throughout his career, certain themes and stylistic characteristics remained constant. His fascination with the ideal, the spiritual, and the allegorical never waned. His figures often possess a statuesque quality, imbued with a sense of grace and timelessness. The use of light and color in his work was carefully considered to create specific moods and enhance the symbolic content. His landscapes, whether serving as backdrops for allegorical scenes or as subjects in their own right, often evoke a sense of poetic melancholy or serene beauty.

Montald also contributed his artistic talents to the design of Belgian banknotes, beginning around 1898. This work, though perhaps less celebrated than his paintings, demonstrates his versatility and his ability to apply his artistic skills to different mediums and purposes. The design of currency offered another avenue for art to reach a wide public, and his contributions are noted for their aesthetic quality.

Critical Reception and Historical Legacy

Constant Montald was a highly respected artist during his lifetime. His winning of the Prix de Rome, his professorship at the prestigious Brussels Academy, and his numerous public commissions attest to the esteem in which he was held. He was recognized as a leading figure of Belgian Symbolism and a master of monumental decoration. His work was seen as embodying a certain Belgian artistic identity, one that balanced technical skill with poetic sensibility.

Like many Symbolist artists, Montald's work sometimes faced criticism for being overly idealized, decorative, or detached from the more radical social and artistic currents of the early 20th century, particularly as movements like Expressionism (with figures like James Ensor in Belgium, albeit with his unique style) and later Surrealism gained prominence. However, this "idealism" was central to the Symbolist ethos, which consciously turned away from gritty realism in favor of exploring inner worlds, spiritual truths, and universal themes.

In the broader history of art, Montald is firmly positioned within the Symbolist movement, alongside international figures such as Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon in France, or Arnold Böcklin in Switzerland. Within Belgium, he stands with Khnopff and Delville as a key exponent of this style. His particular contribution lies in his successful application of Symbolist principles to large-scale, public art, creating works that were intended to be both aesthetically enriching and morally uplifting.

His influence as a teacher also forms a crucial part of his legacy. While his direct stylistic impact on students like Magritte or Delvaux might be debated, his role in their academic formation is undeniable. He contributed to an artistic environment that nurtured a generation of artists who would go on to define Belgian art in the 20th century.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Constant Montald's artistic journey was one of unwavering dedication to a vision of art that was both beautiful and meaningful. From his early academic training to his mature Symbolist works and monumental murals, he consistently sought to express profound ideas and evoke deep emotions. His mastery of color, particularly his signature blues and golds, his skillful handling of the human form, and his ability to create dreamlike and allegorical compositions distinguish his oeuvre.

As a painter, sculptor, muralist, designer, and influential educator, Montald played a multifaceted role in the Belgian art world. His works in public spaces, such as the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels, continue to inspire awe and contemplation. His Villa Montald stands as a testament to his holistic artistic vision, and his legacy as a teacher is carried on through the subsequent achievements of his students.

While artistic tastes and movements have evolved since his time, Constant Montald's contributions remain significant. He represents a vital strand of European Symbolism, one that emphasized idealism, spirituality, and the decorative power of art. His work invites us to look beyond the surface of reality, to explore the realms of myth, dream, and the enduring human quest for meaning and beauty. In the annals of Belgian art history, Constant Montald remains a distinguished and luminous figure.