George Frederick Watts stands as one of the colossal figures of Victorian art, a painter and sculptor whose prolific career spanned much of the 19th century and extended into the dawn of the 20th. Born in London in 1817 and living until 1904, Watts navigated the complex currents of his time, producing an oeuvre marked by profound ambition, technical skill, and a deep engagement with the great themes of human existence: life, death, love, hope, and the spiritual progress of humanity. Often hailed as "England's Michelangelo," he was a key figure in the Symbolist movement, yet his unique vision and methods set him apart. This article delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of this multifaceted artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

George Frederick Watts entered the world on February 23, 1817, in Marylebone, London. His early life was shaped by fragility and loss. His father, also named George, was a maker of musical instruments, particularly pianos, but faced financial instability. Young George suffered from poor health, including persistent headaches that would plague him throughout his life. His mother passed away while he was still a young boy, leaving his father to raise him with a strong, if somewhat austere, foundation in the Christian classics. This early exposure to grand narratives and moral frameworks arguably sowed the seeds for the allegorical nature of his later work.

His artistic inclinations emerged early. Showing a precocious talent for drawing, he gained access to the studio of the sculptor William Behnes around the age of ten, where he learned the fundamentals of form and anatomy by studying classical casts, particularly the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon, housed in the British Museum. This early immersion in Greek sculpture left an indelible mark on his artistic sensibility, fostering a lifelong reverence for classical ideals of form and heroic expression.

In 1835, at the age of 18, Watts enrolled in the Royal Academy Schools. However, his formal training was brief. Finding the academic methods uninspiring, he largely pursued his own path of self-education, driven by an intense curiosity and a dedication to mastering his craft. He spent countless hours studying the Old Masters, particularly the Venetian colorists like Titian and the monumental power of Michelangelo, whose influence would become increasingly apparent in his work. He made his debut at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1837, signaling the start of a long and prominent public career.

The Italian Journey and Broadening Horizons

A pivotal moment arrived in 1842. Watts entered a competition to design large-scale frescoes for the newly rebuilt Houses of Parliament in Westminster, a major national project following a devastating fire. His cartoon, Caractacus Led in Triumph through the Streets of Rome, won a first prize of £300. This prestigious award not only brought him significant recognition but also provided the financial means for a transformative journey.

Using the prize money, Watts traveled to Italy in 1843, initially intending a short visit. However, he ended up staying for four years, primarily in Florence. There, he became part of the circle around Lord Holland, the British envoy, staying at the Casa Feroni (later Palazzo Amerighi) and Villa Careggi. This period was crucial for his artistic development. He immersed himself in the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance, studying frescoes by Giotto and Masaccio, and deepening his admiration for Michelangelo and the Venetian painters, especially Titian, whose rich colours and handling of paint profoundly affected his own technique.

During his time in Italy, Watts painted portraits of Lord and Lady Holland and members of their circle, honing his skills in capturing likeness and character. He also began to conceive ambitious historical and allegorical subjects, inspired by the grandeur of Italian art and history. The experience solidified his belief in the power of art to convey profound ideas and narratives, moving beyond mere representation towards a more symbolic and didactic purpose. He returned to England in 1847 with a broadened perspective and a heightened artistic ambition.

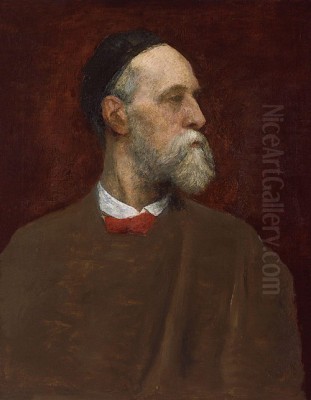

The Portraitist of an Era: The "Hall of Fame"

Upon his return, Watts established himself as one of the preeminent portrait painters of his generation. While he often expressed a preference for his allegorical "epic poems" in paint, his portraits provided a steady income and cemented his reputation within Victorian society. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture not just the physical likeness but the intellectual and moral essence of his sitters, creating works of penetrating psychological depth.

Over several decades, Watts embarked on a personal project he called his "Hall of Fame," a series of portraits documenting the most distinguished figures of his time – poets, statesmen, artists, scientists, and thinkers who shaped the Victorian age. He intended this collection as a gift to the nation, a visual record of its great minds. Sitters included luminaries such as the poets Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning; the painters Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais (key figures of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood); the influential art critic John Ruskin; the philosopher John Stuart Mill; and political giants like William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli.

His portraits often eschewed elaborate backgrounds or fashionable attire, focusing instead on the sitter's face and posture to convey character and gravitas. He sought to reveal the inner life, the intellectual force, or the moral weight of the individual. This approach distinguished his work from more conventional society portraiture. His long-standing friendship and patronage from the Ionides family, particularly Alexander Constantine Ionides, also resulted in numerous portraits, documenting several generations of this prominent Anglo-Greek family and providing crucial support early in his career. Over fifty of these "Hall of Fame" portraits were eventually donated to the National Portrait Gallery in London, fulfilling his patriotic ambition.

Symbolism and the "House of Life"

While excelling in portraiture, Watts's true passion lay in creating large-scale allegorical and symbolic works that addressed universal themes. He famously declared, "I paint ideas, not things." He sought to create a visual language capable of expressing the profound mysteries and struggles of human existence – love, death, hope, despair, faith, greed, and the relentless march of time. This ambition placed him at the forefront of the Symbolist movement in Britain, which reacted against realism and materialism by emphasizing subjective experience, emotion, and the power of suggestion.

Central to this endeavor was his concept of the "House of Life," an ambitious, though never fully realized, cycle of paintings intended to form a grand visual epic charting the spiritual journey of humanity. Many of his most famous allegorical works were conceived as part of this cycle. These paintings often feature monumental, archetypal figures set against atmospheric, dreamlike landscapes, rendered with a distinctive technique that emphasized texture and suggestive form over precise detail.

Among the most celebrated works from this period is Hope (first version c. 1886). It depicts a blindfolded female figure seated atop a globe, hunched over a lyre with all but one string broken. Despite the apparent desolation, she strains to hear the faint music from the single remaining string. The painting became an icon of resilience and endurance in the face of adversity, resonating deeply with audiences worldwide and inspiring figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Barack Obama centuries later.

Other key symbolic works include Love and Life (c. 1884-85), showing a winged, powerful figure of Love guiding the hesitant, vulnerable figure of Life up a rocky path towards the light. Mammon (c. 1884-85) offers a stark critique of materialism, portraying a brutish, richly robed figure crushing youth and beauty beneath his heavy hand. The Minotaur (c. 1885), inspired by newspaper reports of child prostitution, depicts the mythical beast peering out over a city, a symbol of lust and exploitation. The Sower of the Systems (c. 1902) presents a cosmic vision of creation, a swirling, dynamic figure scattering stars across the void, reflecting Watts's interest in science and spirituality. These works, rich in allegory and often ambiguous, invited contemplation and interpretation, aiming to elevate the viewer's thoughts beyond the mundane.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Influences

Watts developed a highly individual artistic style that evolved throughout his long career but consistently bore his unique stamp. His early work shows the influence of classical sculpture and the High Renaissance, particularly Michelangelo, in its emphasis on powerful, muscular forms and dramatic compositions. His time in Italy deepened his appreciation for the rich color and painterly techniques of the Venetian school, especially Titian, which informed his handling of paint and light.

He deliberately moved away from the highly detailed, smooth finish favored by many Victorian contemporaries, including some Pre-Raphaelites like Millais or William Holman Hunt. Instead, Watts embraced a more textured, suggestive approach. He often applied paint thickly (impasto), sometimes using his fingers or palette knives, building up surfaces that were rich, complex, and almost sculptural. He experimented with different media and techniques, sometimes allowing underlayers of paint to show through, creating a sense of depth and vibration. This rejection of smooth surfaces and embrace of visible brushwork gave his paintings a raw, expressive power, particularly in his later, more abstract works.

His color palettes ranged from the rich, jewel-like tones reminiscent of the Venetians to more somber, atmospheric hues in his allegorical pieces. Light in his paintings is often dramatic and symbolic, used to highlight key figures or create a sense of mystery and transcendence. While grounded in academic drawing and anatomical understanding, his figures often possess an archetypal, monumental quality, serving as vessels for abstract ideas rather than specific individuals.

His style was distinct from the Aestheticism of contemporaries like James McNeill Whistler, which prioritized "art for art's sake." Watts believed firmly in the moral and didactic purpose of art. He saw himself as a teacher and prophet, using his art to communicate profound truths. This seriousness of purpose, combined with his technical mastery and classical grounding, led critics to dub him "England's Michelangelo," a comparison he likely found flattering given his deep reverence for the Renaissance master. His later works, like The Sower of the Systems, became increasingly abstract and mystical, prefiguring developments in 20th-century art.

Sculptural Endeavors: Energy in Bronze

Although primarily known as a painter, Watts was also a gifted sculptor, returning to the medium that had first captivated him in William Behnes' studio. His sculptural output was less extensive than his painting but includes some highly significant works, most notably the monumental equestrian statue Physical Energy.

He worked on Physical Energy intermittently for over twenty years, beginning around 1883. The colossal bronze depicts a powerful, nude male rider on a horse, shielding his eyes as he looks towards the horizon. The work is a potent symbol of restless vitality, ambition, and the forward drive of the human spirit – or, as Watts intended, the "vague outreach of human power." It embodies controlled strength and potential, a sense of boundless aspiration.

The first bronze cast was completed shortly after Watts's death in 1904 and became part of the Cecil Rhodes memorial in Cape Town, South Africa. Another cast stands prominently in Kensington Gardens, London, a powerful public monument. A third resides at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Harare. The sculpture showcases Watts's mastery of anatomy and dynamic form, translating the monumental energy of his paintings into three dimensions. It stands as a testament to his enduring belief in progress and human potential, echoing the heroic spirit found in classical sculpture and the work of Michelangelo.

Another notable sculptural collaboration was with his second wife, Mary Fraser Tytler. Together, they worked on pieces like the Sphinx and other decorative elements, particularly for the Watts Chapel. His engagement with sculpture allowed him to explore form and volume in ways that complemented his painterly concerns, reinforcing the classical foundations of his art.

Social Conscience and Public Spirit

Watts was more than just an artist confined to his studio; he was a man deeply engaged with the social and moral issues of his time. He possessed a strong sense of civic duty and believed that art should serve a higher purpose, contributing to the betterment of society. This conviction manifested in various public-spirited actions and themes within his work.

He was a sharp critic of the materialism and social inequalities of the Victorian era. Works like Mammon directly attacked the worship of wealth, while paintings depicting poverty, such as Found Drowned or Under a Dry Arch, highlighted the plight of the urban poor with empathy, though avoiding overt sentimentality. His allegorical works often carried implicit social commentary, urging viewers towards higher ideals.

His patriotism was profound, but it was coupled with a sense of responsibility. This led him to conceive the "Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice," a project dedicated to honoring ordinary people who had lost their lives while saving others. He felt that such acts of everyday heroism deserved national recognition. He researched forgotten instances of bravery, often involving working-class individuals, and commissioned ceramic plaques detailing their sacrifices. The memorial was eventually established in Postman's Park, near St. Paul's Cathedral in London, with the first plaques installed in 1900. After his death, Mary Watts continued the project.

His desire to make art accessible to the public was evident in his generous donations. The gifting of his "Hall of Fame" portraits to the National Portrait Gallery was a major act of philanthropy. He also donated significant allegorical works to the Tate Gallery (then the National Gallery of British Art) and other institutions, ensuring his major statements reached a wide audience. He believed art had the power to educate and uplift, and should not be solely the preserve of the wealthy.

Furthermore, his early success in the Houses of Parliament competition fueled a lifelong dream of creating vast public murals depicting the progress of humanity, though this grand vision was never fully realized on the scale he imagined. His participation in such national projects, his donations, and his memorial all underscore his commitment to art as a public good.

Personal Life, Relationships, and Character

Watts's personal life contained both joy and sorrow. His first marriage, in 1864, was to the celebrated stage actress Ellen Terry, who was nearly thirty years his junior (he was 46, she was just shy of 17). Terry served as a model for some of his paintings during their brief time together. However, the marriage was ill-fated and lasted less than a year, ending in separation and later divorce. The reasons remain debated, but the age gap and differing temperaments likely played significant roles.

His second marriage, in 1886, proved far more enduring and harmonious. He married Mary Fraser Tytler, a talented Scottish artist and designer in her own right, who was 33 years his junior. Mary became his devoted companion, collaborator, and tireless supporter. She assisted him in his studio, managed his affairs, and played a crucial role in establishing their home and artistic enterprises in Compton, Surrey. Their partnership was both personal and professional, culminating in shared projects like the Watts Chapel.

Throughout his life, Watts cultivated friendships with many leading figures in the arts and letters. He was close to fellow artists like Frederic Leighton, president of the Royal Academy, and maintained connections with members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle like Edward Burne-Jones, despite stylistic differences. His sitters often became friends, including Tennyson, whose portrait he painted multiple times. His association with the archaeologist Sir Charles Thomas Newton, whom he accompanied on an expedition to excavate the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus in 1856-57, broadened his understanding of classical antiquity.

Watts was known for his dignified, almost prophetic bearing, often dressing in Renaissance-style robes. He was deeply serious about his art and its purpose. Despite his fame, he maintained a degree of detachment from societal expectations. This was famously demonstrated by his twice refusing a baronetcy offered by Queen Victoria (first in 1885, then again in 1894), preferring to remain, as he put it, an "untitled patriot and artist." He did, however, accept the newly instituted Order of Merit in 1902, recognizing it as an honour specifically for achievement rather than inherited status. His independence, moral seriousness, and dedication to his vision defined his character.

The Watts Chapel and the Compton Legacy

In the later part of his life, Watts and his wife Mary sought refuge from the bustle of London. They commissioned the architect Ernest George to build a house, Limnerslease, near Compton, a village in Surrey, moving there in 1891. Compton became the center of their artistic world and the site of their most unique collaborative project: the Watts Chapel.

Designed by Mary Watts and built between 1895 and 1898, the chapel (originally intended as a mortuary chapel for the Compton cemetery) is an extraordinary fusion of Art Nouveau, Celtic, Romanesque, and Egyptian influences, filtered through the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement. While George Watts funded the project and provided overall guidance, Mary led the design and execution, training local villagers in terracotta modeling techniques. The exterior is a striking structure of red brick and ornate terracotta, featuring intricate symbolic reliefs designed by Mary.

The interior, completed after George's death under Mary's supervision (finished 1904), is even more breathtaking. Every surface is covered in vibrant gesso relief work, painted and gilded, depicting angels, spiritual symbols, and swirling decorative patterns in a style that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. The chapel stands as a unique monument to the Wattses' shared spiritual and artistic vision and Mary's own considerable talents as a designer and organizer.

Adjacent to Limnerslease, the Wattses also established the Watts Gallery (opened 1904, shortly before George's death) to display his work permanently, fulfilling his wish for a dedicated space for his art. Mary also founded the Compton Potters' Arts Guild, providing employment and artistic training for local people, further embedding their artistic legacy within the community. Today, the Watts Gallery – Artists' Village preserves this rich heritage, encompassing the historic gallery, Limnerslease, the chapel, and studios.

Later Years, Death, and Fluctuating Reputation

George Frederick Watts remained artistically active into his eighties, continuing to paint and sculpt with undiminished energy and ambition. His later works often took on an increasingly mystical and cosmic quality, exploring themes of creation, dissolution, and the vastness of the universe, as seen in paintings like The Sower of the Systems. He continued to refine his symbolic language, pushing towards a form of abstraction rooted in spiritual ideas.

He passed away at Limnerslease on July 1, 1904, at the age of 87. At the time of his death, he was widely regarded as one of Britain's greatest artists, a national treasure revered for his technical skill, intellectual depth, and moral seriousness. His funeral was a major event, and tributes poured in from across the country and beyond.

However, the early 20th century brought seismic shifts in artistic taste. The rise of Modernism, with its emphasis on formal innovation, abstraction derived from different sources (like Cubism or Fauvism), and often a rejection of Victorian narrative and moralizing, led to a decline in Watts's critical standing. His allegorical works, once praised for their profundity, were sometimes dismissed as obscure, overly literary, or even pretentious. Figures associated with the Bloomsbury Group, like Virginia Woolf (who satirized the Victorian milieu, including Watts's circle, in her play Freshwater), represented a new generation that found Victorian high-mindedness stifling.

For much of the mid-20th century, Watts was somewhat overlooked, considered a relic of a bygone era. However, towards the end of the century and into the 21st, there has been a significant reappraisal of his work. Art historians and the public have rediscovered the power and complexity of his paintings and sculptures. His role as a precursor to Symbolism and even certain forms of abstraction is now better appreciated. His technical skill, the psychological depth of his portraits, and the sheer ambition of his allegorical projects are recognized anew. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have shed fresh light on his achievements, restoring him to a prominent place in the history of British art.

Enduring Legacy

George Frederick Watts left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of Britain and beyond. He was a bridge figure, deeply rooted in the classical and Renaissance traditions yet grappling with the anxieties and aspirations of modernity. His commitment to art as a vehicle for profound ideas set him apart from purely aesthetic trends, while his technical mastery earned him the respect of his peers.

His legacy endures through his vast body of work, housed in major galleries worldwide, particularly the Tate Britain, the National Portrait Gallery, and the dedicated Watts Gallery – Artists' Village in Compton. His portraits provide an unparalleled visual record of the intellectual and political giants of the Victorian age. His symbolic paintings, especially Hope, continue to resonate with audiences, offering timeless reflections on the human condition. His public sculptures, like Physical Energy, remain powerful landmarks.

Beyond the artworks themselves, Watts's legacy lies in his unwavering belief in the power of art to elevate the human spirit and engage with the great questions of life. He demonstrated that art could be both technically brilliant and intellectually ambitious, both deeply personal and publicly spirited. As a painter, sculptor, portraitist, symbolist, and social commentator, George Frederick Watts remains a towering figure, a Victorian visionary whose complex and compelling work continues to inspire and provoke thought today.