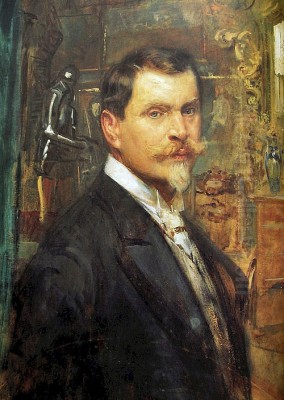

Eduard Veith (1856-1925) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Austrian art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter and stage designer of considerable talent, Veith navigated the dynamic artistic currents of his time, leaving behind a legacy of opulent decorative schemes, evocative portraits, and symbolically charged compositions. His work, deeply rooted in the academic traditions yet touched by the burgeoning Symbolist movement, adorned many of the Austro-Hungarian Empire's most prestigious public buildings and private residences, reflecting the cultural ambitions and aesthetic sensibilities of an era on the cusp of profound change.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Eduard Veith was born in 1856 in Neutitschein, Moravia (now Nový Jičín, Czech Republic), then part of the Austrian Empire. His father, Julius Veith, was a decorative painter and carpenter, an environment that likely provided young Eduard with his initial exposure to the arts and crafts. This familial background in decorative work would prove influential, as much of Veith's later success lay in large-scale mural and ceiling paintings.

His formal artistic training began at the prestigious Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule), a crucible for many talents who would shape the visual culture of the era. Here, he studied under Ferdinand Laufberger, a respected painter and illustrator known for his historical scenes and decorative works. Laufberger's tutelage would have instilled in Veith a strong foundation in academic drawing, composition, and the techniques required for monumental painting. The Kunstgewerbeschule itself, closely associated with the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry (today the MAK), emphasized the integration of art into everyday life and the importance of high-quality craftsmanship, ideals that resonated throughout Veith's career.

The Parisian Sojourn and Stylistic Development

To further hone his skills and broaden his artistic horizons, Veith, like many aspiring artists of his generation, traveled to Paris. The French capital was then the undisputed center of the art world, a vibrant hub of innovation and tradition. While the specifics of his Parisian studies are not exhaustively detailed, this period would have exposed him to a wide array of artistic influences, from the established academic salons to the more avant-garde movements that were beginning to challenge conventional aesthetics.

It was likely during this time, or shortly thereafter, that Veith began to absorb the influences of Symbolism. This late 19th-century movement, which sought to express subjective truths and spiritual realities through suggestive imagery and metaphorical narratives, found fertile ground across Europe. Artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes in France, or Fernand Khnopff in Belgium, were exploring themes of dreams, mythology, and the inner life, often employing a refined, sometimes melancholic, aesthetic. Veith's own inclination towards allegorical subjects and his nuanced portrayal of emotion suggest a keen engagement with these Symbolist currents.

Upon his return to Austria, Veith's style began to crystallize. It was a sophisticated blend: the rigorous draftsmanship and compositional clarity of his academic training, the decorative sensibility perhaps inherited from his father and nurtured at the Kunstgewerbeschule, and an increasing infusion of Symbolist mood and meaning. He became particularly adept at creating large-scale decorative works, a skill highly sought after during the Ringstrasse era in Vienna, a period of immense urban development and architectural grandeur.

A Flourishing Career in Vienna: Monumental Decorations

Eduard Veith established himself as a prominent artist in Vienna, receiving numerous commissions for significant public and private buildings. His ability to work on a grand scale, creating harmonious and thematically rich decorative schemes, made him a favored choice for architects and patrons. He was part of a generation of artists, including figures like Hans Makart, whose opulent historical and allegorical paintings had set a precedent for Viennese monumental art. While Makart's influence was pervasive, Veith, along with contemporaries like Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch who initially worked in a similar historical-academic style, began to forge their own paths.

One of Veith's most notable commissions was for the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, the imperial residence. He contributed to the decoration of the Maria Theresia Hall, creating ceiling paintings that exemplified his skill in allegorical representation and his command of complex compositions. These works, often depicting mythological or historical scenes, were designed to complement the architectural splendor of the spaces they inhabited, imbuing them with cultural and symbolic resonance. His murals could also be found in other significant Viennese locations and extended to cities like Prague, then also part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Veith's approach to these monumental projects was characterized by a careful balance of elements. His figures were often rendered with a classical sense of form and idealized beauty, yet they were imbued with a psychological depth and emotional subtlety that hinted at Symbolist concerns. His color palettes were rich and harmonious, contributing to the overall decorative effect without sacrificing narrative clarity. He demonstrated a remarkable versatility, adapting his style to suit the specific requirements of each commission, whether it was a grand imperial hall, a municipal building, or a private residence.

The Symbolist Vein in Veith's Art

While Veith was a master of large-scale public decoration, his oeuvre also includes numerous easel paintings and portraits where his engagement with Symbolism is perhaps most apparent. Symbolist artists sought to evoke ideas and emotions rather than merely depict objective reality. They often drew upon mythology, dreams, literature, and religious mysticism to create works that were suggestive and open to multiple interpretations.

Veith's works in this vein often feature enigmatic female figures, allegorical personifications, and dreamlike landscapes. Titles such as "Venus and Cupids," a large allegorical painting, point directly to mythological themes, but his treatment often transcends simple illustration, imbuing these ancient stories with a contemporary sensibility and psychological nuance. This particular work is considered a significant example of the Austrian decorative school of painting at the end of the 19th century, showcasing his ability to blend classical subject matter with a modern, almost sensuous, aesthetic.

His female portraits, in particular, often carry a Symbolist charge. These are not merely likenesses but explorations of mood, character, and an idealized, often mysterious, femininity. Works like "Portrait of a Young Girl," "Portrait of an Elegant Lady," and "Profile of a Young Woman Holding a Rose" suggest a fascination with capturing an inner essence, a fleeting emotion, or a symbolic attribute. The delicate rendering of features, the careful attention to costume and accessories, and the often contemplative or introspective expressions of his sitters contribute to the evocative power of these paintings. In this, he shared a certain affinity with other European Symbolists like Franz von Stuck or even the early, more academic phases of Gustav Klimt.

Mastery in Portraiture

Beyond his allegorical and mythological subjects, Eduard Veith was a highly accomplished portrait painter. His portraits were sought after by the Viennese elite, and he captured the likenesses of numerous prominent individuals. His approach to portraiture combined technical finesse with an ability to convey the personality and status of his sitters.

His female portraits, as mentioned, often carried Symbolist undertones, but even his more straightforward commissioned portraits reveal a keen eye for detail and a sophisticated understanding of human psychology. He was adept at capturing the textures of fabrics, the glint of jewelry, and the subtle nuances of expression that bring a painted likeness to life. These portraits serve not only as records of individual appearances but also as documents of the social and cultural milieu of fin-de-siècle Vienna.

The elegance and refinement of Veith's portrait style resonated with the tastes of his clientele. He managed to flatter his subjects without sacrificing a sense of realism, creating images that were both aesthetically pleasing and psychologically insightful. This skill placed him among the respected portraitists of his day, in a city that boasted a rich tradition of portrait painting.

The Art of Stage Design: Collaborations with Fellner & Helmer

Eduard Veith's artistic talents were not confined to painting. He was also a highly regarded stage designer, a field that allowed him to combine his skills in composition, color, and dramatic effect on a grand scale. He frequently collaborated with the renowned architectural firm Fellner & Helmer, who were responsible for designing and building numerous theaters and opera houses across Central and Eastern Europe.

Ferdinand Fellner the Younger and Hermann Helmer's firm built iconic venues such as the Vienna Volkstheater, the Ronacher, the Graz Opera, the State Opera and National Theatre in Prague, and theaters in Budapest, Zurich, and many other cities. Veith's role in these collaborations was to create the lavish interior decorations, including stage curtains, proscenium arch embellishments, and sometimes entire decorative schemes for auditoriums and foyers. His designs for the theater were integral to the overall experience, creating an atmosphere of opulence and fantasy that complemented the dramatic performances on stage.

His work in stage design required a deep understanding of perspective, lighting, and the practical demands of theatrical production. He created elaborate painted backdrops and scenic elements that transported audiences to different worlds, from historical settings to mythical realms. This aspect of his career highlights his versatility and his ability to apply his artistic vision to diverse contexts. His contributions to theater design were significant, enhancing the visual splendor of many of the most important performance venues of the era. For instance, his work graced the interiors of the Prague National Opera House and the "Unter den Linden" Theater (likely referring to a theater in a city with such a named street, perhaps Berlin, or a Viennese establishment with a similar evocative name).

Veith as Educator: Shaping a New Generation

In addition to his prolific career as a practicing artist, Eduard Veith also dedicated part of his life to teaching. His reputation and expertise led to academic appointments that allowed him to pass on his knowledge and skills to younger generations of artists. In 1905, he was appointed a professor at the Vienna Technical University (Technische Hochschule Wien, now TU Wien). This was a significant recognition, as technical universities often included departments of architecture and design where artistic instruction was crucial.

Later, in 1920, he became a professor at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule), the very institution where he had received his early training. Returning to his alma mater as a professor was a testament to his standing in the Viennese art world. In these teaching roles, Veith would have influenced students across various disciplines, from aspiring painters and decorators to architects and designers. His emphasis on solid craftsmanship, combined with his sophisticated aesthetic sense, would have provided a valuable foundation for his students. His teaching career underscores his commitment to the broader artistic community and his role in nurturing future talent.

Contemporaries and the Viennese Artistic Milieu

Eduard Veith worked during a period of extraordinary artistic ferment in Vienna. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the decline of the historical academicism that had dominated the Ringstrasse era and the rise of new movements, most notably the Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 by artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Carl Moll, and Josef Hoffmann. The Secessionists sought to break away from the conservative Künstlerhaus (the established artists' association) and create a modern Austrian art.

While Veith was not a member of the Secession's radical core, his work shares certain affinities with the broader artistic trends of the time, particularly the interest in Symbolism and decorative integration. He collaborated with other artists on large projects, such as the decorations for the Hofburg Palace, where he worked alongside painters like Alois Schramm and Viktor Stauffer. In the Festsaal of the Hofburg, for example, Veith was responsible for painting figures of Austrian historical rulers like Maximilian I, Charles V, Ferdinand I, Rudolph II, and Ferdinand II in the lower lunettes and octagonal fields, while Stauffer depicted other historical figures like Leopold I and Prince Eugene on the side walls. Such collaborations were common in large-scale decorative projects.

The artistic landscape was diverse. While Klimt was pushing the boundaries with his increasingly abstract and erotically charged Symbolist works, other artists continued to work in more traditional modes, or explored different facets of modernism. Veith occupied a space that bridged the academic tradition and the newer Symbolist tendencies. He maintained a high level of craftsmanship and a commitment to representational clarity, even as he explored themes of interiority and allegory. His success in securing major public and private commissions throughout this period indicates that his style resonated with influential patrons and the broader public. He was part of a vibrant ecosystem of artists, architects, and designers who collectively shaped the unique cultural identity of fin-de-siècle Vienna. One can also see parallels or contextual links to broader European academic and Symbolist painters like Lawrence Alma-Tadema for his historical precision, or the aforementioned French and Belgian Symbolists.

Awards, Recognition, and Later Years

Eduard Veith's contributions to the art world did not go unrecognized during his lifetime. He received several accolades for his work, a testament to the high regard in which he was held. A significant honor was the Gold Medal he received at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition in 1896. International exhibitions like this were crucial platforms for artists to gain wider recognition and establish their reputations beyond their home countries.

He continued to be active as a painter and decorator throughout the early decades of the 20th century, adapting to changing tastes while maintaining his distinctive style. The world around him was undergoing profound transformations, with the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I and the dawn of a new, often turbulent, era. Veith's art, with its roots in the imperial grandeur and Symbolist introspection of the late 19th century, remained a touchstone of that earlier period.

Eduard Veith passed away in Vienna on March 18, 1925, at the age of 69 (or 67 if the less-cited 1858 birth year were accurate, though 1856 is more consistently referenced). He was laid to rest in the Döbling Cemetery (Döblinger Friedhof) in Vienna. His grave is marked by a sculpture created by Georg Leisik, a fitting tribute to an artist who had dedicated his life to the visual arts.

Legacy and Conclusion

Eduard Veith's legacy is that of a highly skilled and versatile artist who made significant contributions to the visual culture of Austria and Central Europe at the turn of the 20th century. As a painter of monumental decorative schemes, he embellished numerous important buildings, creating works that harmonized with their architectural settings and conveyed rich allegorical and historical narratives. His ceiling paintings in the Hofburg Palace and his decorative work in theaters stand as testaments to his mastery in this demanding field.

In his easel paintings and portraits, Veith demonstrated a subtle engagement with Symbolism, exploring themes of mythology, allegory, and the inner lives of his subjects, particularly his evocative portrayals of women. His technical proficiency, combined with a refined aesthetic sensibility, earned him acclaim and a steady stream of commissions.

As a stage designer, he collaborated with leading architects to create immersive and visually stunning theatrical environments. And as an educator, he played a role in shaping the next generation of artists. While perhaps not as radical an innovator as some of his Secessionist contemporaries, Eduard Veith was a pivotal figure whose art beautifully encapsulated the transition from 19th-century historicism to the more introspective and decorative concerns of early modernism. His work remains an important part of Austria's artistic heritage, offering a window into the cultural aspirations and aesthetic ideals of a fascinating and transformative era. His ability to seamlessly blend academic rigor with Symbolist depth, and decorative grandeur with intimate portraiture, marks him as a truly accomplished artist of his time.