Corrado Giaquinto stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of 18th-century European art. An Italian painter of prodigious talent and remarkable adaptability, he navigated the transition from the late Baroque to the full flowering of the Rococo style. Born in Molfetta, near Bari in southern Italy, on February 8, 1703, Giaquinto's career would take him from the vibrant artistic centers of Naples and Rome to the prestigious court of Spain in Madrid. His work, characterized by luminous color, dynamic compositions, and an elegant sensibility, left an indelible mark not only on Italian painting but also significantly shaped the course of art in Spain. He passed away in Naples on April 18, 1766, leaving behind a rich legacy of frescoes, altarpieces, and easel paintings.

Formative Years in Southern Italy

Giaquinto's artistic journey began in his native Apulia. His initial training was under a local Molfetta painter, Saverio Porta, which likely provided him with the foundational skills necessary for a budding artist. However, the lure of a more dynamic artistic environment soon drew him to Naples, a city pulsating with creative energy and a major center for Baroque art. It was here, around 1719, that Giaquinto entered the bustling workshop of Francesco Solimena, one of the most dominant figures in Neapolitan painting at the time.

Solimena's studio was a crucible of talent, and his own style, a dramatic and richly colored interpretation of the Baroque, deeply influenced his pupils. Solimena himself was indebted to the legacy of Luca Giordano, the famously swift and prolific painter whose dazzling frescoes and canvases had set a high bar for Neapolitan art. Giaquinto absorbed these influences, learning the importance of grand compositions, expressive figures, and the skillful manipulation of light and shadow that characterized the Neapolitan school. The impact of both Solimena and Giordano would resonate throughout Giaquinto's career, providing a foundation upon which he would build his own distinctive style. He worked alongside other aspiring artists in Solimena's circle, likely including figures such as Francesco de Mura.

Forging a Reputation in Rome

Seeking broader horizons and greater opportunities, Corrado Giaquinto relocated to Rome in 1727. The Eternal City was still the undisputed center of the art world, attracting artists from across Europe. Here, Giaquinto rapidly established himself, adapting his Neapolitan training to the prevailing artistic currents in Rome. He engaged with the legacy of Roman Baroque masters but also embraced the emerging Rococo sensibility, characterized by lighter palettes, more graceful forms, and themes often leaning towards the decorative and elegant.

His talent did not go unnoticed. Giaquinto began receiving important commissions for church decorations and easel paintings. He developed a reputation for his refined technique, his brilliant use of color, and his ability to create compositions that were both complex and harmonious. He became one of the leading figures of the Roman Rococo, competing and interacting with other prominent artists active in the city during this period, such as Sebastiano Conca and the portraitist Pompeo Batoni. His Roman works demonstrate a sophisticated synthesis of the dramatic energy learned in Naples with a newfound Rococo grace and luminosity, setting the stage for his international renown.

The Call to Madrid

Giaquinto's fame reached the ears of the Spanish monarchy. In 1753, he received a prestigious invitation from King Ferdinand VI of Spain to move to Madrid. This marked a significant turning point in his career, elevating him to the highest echelons of European court art. The Spanish Bourbon court, like others across Europe, actively sought leading international artists to enhance its prestige and undertake ambitious decorative projects. Giaquinto followed in the footsteps of other Italian artists who had found favor in Spain, such as Jacopo Amigoni.

In Madrid, Giaquinto was showered with honors and responsibilities. He was appointed First Court Painter (Primer Pintor de Cámara), a position of immense influence. Furthermore, he was named Director of the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando (Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando), placing him at the forefront of artistic education in Spain. He was also entrusted with the artistic supervision of the Royal Tapestry Factory (Real Fábrica de Tapices), overseeing the designs for luxurious tapestries intended for the royal palaces. These roles cemented his status as a dominant force in the Spanish art scene for nearly a decade.

Monumental Works for the Spanish Crown

During his tenure in Madrid (1753-1762), Giaquinto undertook several major commissions, primarily for the decoration of the Royal Palace (Palacio Real). His frescoes and large-scale canvases from this period exemplify the grandeur and elegance of the Rococo style adapted to the needs of royal propaganda and representation. Among his most celebrated Spanish works is the sketch or bozzetto for Spain Pays Homage to Religion and the Church (c. 1753), now housed in the Prado Museum, which relates to the decoration of the palace and allegorically represents the piety and power of the Spanish monarchy.

Perhaps his most impressive surviving fresco cycle in Madrid is found in the Hall of Columns (Salón de Columnas) of the Royal Palace. Here, he executed The Birth of the Sun and the Triumph of Bacchus (1761), a complex allegorical work celebrating the monarchy and the natural order, likely referencing the King or the Spanish realm. These works are characterized by their airy compositions, pastel palettes, swirling movement, and mythological or allegorical themes, perfectly embodying the international Rococo style favored by the court. His work in the palace contributed significantly to its opulent interior decoration.

Giaquinto's Evolving Style

Corrado Giaquinto's artistic style is primarily defined by its adherence to Rococo principles, yet it retains a distinctive character shaped by his unique background. His Neapolitan training under Solimena instilled in him a sense of drama and a love for rich, vibrant color. His Roman experience refined his compositions and introduced a greater elegance and classical balance. The influence of Luca Giordano's fluid brushwork and luminous effects is also palpable throughout his career.

His paintings typically feature graceful figures, often arranged in dynamic, asymmetrical compositions. He possessed an exceptional sensitivity to light, using it to create ethereal atmospheres and highlight key elements within the scene. His palette is often bright and varied, employing soft pinks, blues, yellows, and golds to achieve a sense of lightness and opulence. While fundamentally Rococo, some scholars note a subtle shift during his Spanish period, possibly towards a greater refinement or a more controlled elegance that might hint at the emerging Neoclassical tastes, although this remains a point of discussion. This potential evolution could reflect his adaptation to the specific demands of the Spanish court or the broader shifts occurring in European art. His mastery extended from vast ceiling frescoes to intimate cabinet pictures.

Mastery Across Genres

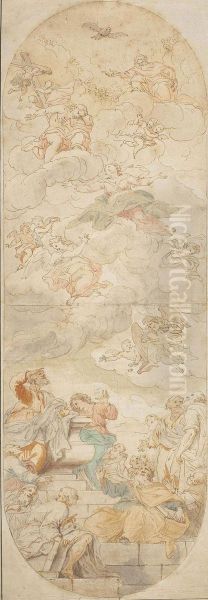

Giaquinto demonstrated remarkable versatility throughout his career, excelling in various genres and formats. While renowned for his large-scale decorative frescoes in churches and palaces, he was equally adept at creating powerful altarpieces, captivating mythological scenes, and smaller devotional paintings. Religious themes formed a significant part of his output, reflecting the demands of his patrons in both Italy and Spain.

Works like The Penitent Magdalen (c. 1750) showcase his ability to convey deep emotion and psychological nuance through delicate brushwork and subtle use of light and shadow. His depictions of the Assumption of the Virgin (he painted this theme multiple times, including notable versions around 1738-39) are characterized by dynamic, swirling compositions that guide the viewer's eye towards the heavens, filled with celestial light and angelic figures. Christ Crucified with the Madonna highlights his skill in rendering dramatic scenes with intense pathos, employing strong chiaroscuro reminiscent of his Baroque roots. Mythological subjects, such as The Triumph of Galatea, allowed him to explore dynamic movement and sensual forms, often intended as designs for other media like tapestry.

Artistic Circles: Teachers, Rivals, and Successors

Giaquinto's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic relationships. His debt to his teachers, Saverio Porta and especially Francesco Solimena, was foundational. The pervasive influence of Luca Giordano, transmitted partly through Solimena, shaped his approach to color and composition. In Rome, he navigated a competitive environment alongside figures like Sebastiano Conca and Pompeo Batoni.

His contemporary, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, represents a parallel giant of the Italian Rococo, particularly famed for his vast frescoes in Venice, Würzburg, and later, Madrid itself (arriving shortly after Giaquinto left). While direct collaboration is not documented, Giaquinto and Tiepolo operated at the highest levels of European patronage, representing the pinnacle of Italian decorative painting in the 18th century. They were likely aware of each other's work and may have been seen as rivals for prestigious international commissions.

Giaquinto's impact was particularly profound in Spain. His role as Academy Director and his prominent works provided a powerful model for the next generation of Spanish painters. Artists like Antonio González Velázquez and Mariano Salvador Maella clearly absorbed his Rococo style. Perhaps most significantly, the young Francisco Goya, who arrived in Madrid later, undoubtedly studied Giaquinto's frescoes in the Royal Palace. Elements of Giaquinto's luminous palette, free brushwork, and compositional dynamism can be discerned as influences on Goya's early development, forming a crucial link between the Italian Rococo and the future of Spanish painting.

Challenges and Unfinished Projects

Despite his success, Giaquinto's later career, particularly the end of his Spanish sojourn, faced challenges. The death of his patron, King Ferdinand VI, in 1759, and the accession of Charles III brought changes to the court's artistic direction. Charles III favored the burgeoning Neoclassical style, championed by the German painter Anton Raphael Mengs, who arrived in Madrid in 1761. This shift in taste likely contributed to Giaquinto's decision to leave Spain in 1762.

The changing climate may also explain why some projects initiated under Giaquinto remained unfinished. Plans for series of tapestries based on his designs, such as cartoons depicting Medea Rejuvenating Aeson or The Triumph of Galatea, were apparently not fully realized or were interrupted. These incomplete ventures hint at the complexities of court patronage, where artistic projects were often subject to political shifts, changes in royal favor, and evolving aesthetic preferences.

Personal Touches and Scholarly Interest

Beyond the grand commissions and official roles, glimpses of the artist's personal life and specific working methods occasionally emerge, though often shrouded in anecdote or requiring further investigation. There is speculation, for instance, that Giaquinto may have used his wife as a model for some figures in his paintings. While adding a humanizing touch, such practices, especially if applied to religious figures, could sometimes attract comment or controversy, though concrete evidence is often scarce.

Despite Giaquinto's clear importance and the presence of his works in major international museums like the Prado, the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and numerous churches and collections across Italy and Spain, some aspects of his oeuvre invite deeper scholarly attention. The precise iconography, dating, or context of certain works, such as the aforementioned Penitent Magdalen, continue to be subjects of study, highlighting that even well-regarded artists can retain areas of mystery or require fresh interpretation. His unique position, blending Neapolitan, Roman, and broader European Rococo elements, makes his artistic trajectory a fascinating case study.

Return to Naples and Final Years

In 1762, Corrado Giaquinto left Madrid and returned to Naples, the city where he had received his formative artistic training decades earlier. He spent the last few years of his life in this familiar environment, though details of his activities during this final period are less documented than his time in Rome and Madrid. He passed away in Naples on April 18, 1766, at the age of 63. His journey had taken him from provincial Molfetta to the artistic capitals of Italy and the royal court of Spain, marking him as a truly international figure of his time.

Enduring Legacy

Corrado Giaquinto remains a significant figure in the history of 18th-century art. He was a leading exponent of the Italian Rococo, demonstrating exceptional skill in both fresco and oil painting. His ability to synthesize various influences – the drama of the Neapolitan Baroque, the elegance of Roman classicism, and the lightness of the international Rococo – resulted in a distinctive and highly appealing style. His decade in Spain was particularly impactful, where he not only executed major decorative schemes but also played a crucial role in shaping the direction of the Royal Academy and influencing a generation of Spanish artists, most notably Francisco Goya. Giaquinto's work stands as a testament to the vibrancy, elegance, and technical brilliance of the Rococo era, bridging artistic traditions and leaving a lasting imprint on the art of both Italy and Spain.