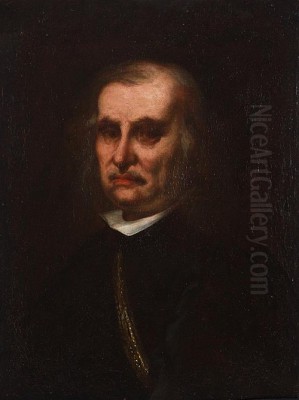

Juan Carreño de Miranda stands as a monumental figure in the annals of Spanish art, a painter whose prolific output and distinguished career bridged the gap between the towering genius of Diego Velázquez and the later masters of the Madrid School. Active during the latter half of the Spanish Golden Age, or Siglo de Oro, Carreño's artistry graced both the solemn interiors of churches and the opulent halls of the royal court. His legacy is one of remarkable versatility, technical brilliance, and an unwavering dedication to his craft, securing his position as one of Spain's most significant Baroque painters.

The Making of a Master: Early Life and Artistic Formation

Juan Carreño de Miranda was born in Avilés, a coastal town in the northern Spanish principality of Asturias, on March 25, 1614. His family, though possessing noble lineage, was not affluent. This background perhaps instilled in him a sense of diligence and a pragmatic approach to his career. Around the age of nine, in 1623, his family relocated to Madrid, the vibrant political and cultural heart of the Spanish Empire. It was here that the young Carreño would embark on his artistic journey.

His initial training was under the tutelage of Pedro de las Cuevas, a respected though not exceptionally famous painter in Madrid. De las Cuevas's studio was known more for its rigorous drawing instruction than for producing groundbreaking artists, but it provided a solid foundation. Subsequently, Carreño studied with Bartolomé Román, a painter whose style was more aligned with the prevailing naturalism influenced by Caravaggio, albeit in a somewhat moderated Spanish vein. These early apprenticeships exposed Carreño to the fundamental techniques of oil painting, composition, and the diverse subject matter demanded by patrons of the era.

Even in his formative years, Carreño demonstrated an exceptional aptitude that reportedly surpassed that of his instructors. By his early twenties, he was already operating as an independent master, a testament to his precocious talent and ambition. The artistic environment of Madrid in the 1630s and 1640s was incredibly rich. The court of Philip IV was a magnet for artistic talent, with Diego Velázquez firmly established as the leading royal painter. The influence of Venetian masters like Titian and Tintoretto, whose works filled the royal collections, was pervasive, as was the dramatic realism of Jusepe de Ribera, who, though based in Naples, exerted considerable influence in Spain. Carreño absorbed these influences, forging a style that was both indebted to tradition and distinctly his own.

In 1639, Carreño married María de Miranda, a woman who shared his noble, albeit modest, background. His personal life remains relatively obscure, with historical records focusing primarily on his professional achievements. His early independent works likely included religious commissions for monasteries and churches in and around Madrid, a staple for painters of the period. One of his earliest documented works is St. Anthony Preaching to the Fish, dated to 1646, which already showcases his burgeoning skill in composition and narrative.

Ascendancy in the Madrid School

Throughout the 1640s and 1650s, Carreño's reputation grew steadily. He became a prominent member of the Madrid School, a term used to describe the constellation of artists working in the capital, often characterized by a blend of naturalism, Venetian colorism, and Baroque dynamism. He undertook numerous commissions for religious institutions, producing altarpieces and devotional paintings that demonstrated his mastery of sacred iconography and his ability to convey profound spiritual emotion.

His style during this period shows an increasing sophistication. While the influence of Velázquez is discernible, particularly in the dignified realism of his figures and the subtle handling of light, Carreño developed a softer touch and a richer, sometimes more vibrant, color palette. He was also adept at large-scale compositions, managing complex groups of figures with clarity and dramatic effect. His work often displayed a particular sensitivity to texture and fabric, rendering silks, velvets, and ecclesiastical vestments with convincing tactility.

A significant aspect of Carreño's career during this time was his involvement in decorative projects, often in collaboration with other artists. Fresco painting was a vital part of church and palace decoration, and Carreño proved proficient in this demanding medium. He frequently collaborated with Francisco Rizi, another leading painter of the Madrid School. Rizi, known for his dynamic compositions and somewhat more exuberant style, complemented Carreño's more measured approach. Together, they worked on numerous projects, including decorative schemes for churches and, importantly, for the Royal Alcázar of Madrid.

In 1658, Carreño's skill and reliability earned him a significant appointment as an assistant on a royal commission for the decoration of the Alcázar. This brought him into closer contact with the court and with Velázquez himself, who, as Aposentador Mayor de Palacio (Grand Marshal of the Palace), oversaw many such artistic enterprises. This proximity to the pinnacle of royal patronage was crucial for Carreño's subsequent career trajectory.

The King's Painter: Service to the Crown

The death of Diego Velázquez in 1660 left a void at the Spanish court. While no single artist could immediately fill the shoes of such a titan, Carreño de Miranda was among the most qualified and respected painters to carry forward the tradition of royal portraiture and courtly art. His earlier work in the Alcázar had not gone unnoticed, and his reputation for excellence was well established.

In 1669, Juan Carreño de Miranda was officially appointed Pintor del Rey (King's Painter) to Charles II, the last Habsburg monarch of Spain. This was a prestigious position, signifying the highest level of royal favor. Two years later, in 1671, he was further elevated to the role of Pintor de Cámara (Court Painter), a position that Velázquez had held with such distinction. This appointment solidified Carreño's status as the leading painter at the Spanish court.

His duties as Court Painter were manifold. He was responsible for producing official portraits of the King, Queen Mariana of Austria (the Queen Mother and Regent during Charles II's minority), and other members of the royal family and the court. These portraits served not only as personal likenesses but also as crucial instruments of statecraft, projecting an image of majesty and authority. Carreño also continued to contribute to the decoration of royal residences, including creating allegorical and mythological scenes.

The reign of Charles II was a period of significant political and economic decline for Spain. The King himself was physically frail and beset by health problems, a stark contrast to the robust image of his Habsburg predecessors. Carreño's portraits of Charles II are poignant historical documents, capturing the young monarch's melancholic demeanor and the somber atmosphere of the court. Unlike the often-idealized portraits of earlier rulers, Carreño's depictions of Charles II are characterized by a sensitive, almost sympathetic realism. He did not shy away from portraying the King's distinctive Habsburg features, yet he imbued these images with a sense of dignity and regal bearing.

His portraits of Queen Mariana of Austria are equally compelling. Often depicted in the austere widow's weeds she adopted after the death of Philip IV, these portraits convey her formidable personality and the burdens of her regency. Carreño masterfully captured the textures of her elaborate mourning attire and the psychological depth of her expression. These works stand as powerful examples of Baroque portraiture, rivaling those of his contemporaries across Europe, such as the Flemish master Anthony van Dyck, whose elegant courtly style had a lasting impact on European portraiture, including in Spain.

Masterpieces of Faith: Religious and Allegorical Works

While his role as a court portraitist was central to his later career, Juan Carreño de Miranda continued to be a prolific painter of religious subjects. The Counter-Reformation had profoundly shaped Spanish art, fostering a demand for works that were both doctrinally sound and emotionally engaging. Carreño excelled in this genre, creating altarpieces and devotional paintings that adorned churches and private chapels throughout Madrid and beyond.

One of his most celebrated religious works is The Foundation of the Trinitarian Order, also known as The Mass of St. John of Matha. This large-scale altarpiece, painted around 1666 for the Trinitarian Church in Pamplona (though some sources suggest it was for a Madrid church), is a masterpiece of Baroque composition and drama. The painting depicts St. John of Matha, co-founder of the Trinitarian Order (dedicated to ransoming Christian captives), celebrating Mass when an angel appears, presenting two captives, one Christian and one Moor, symbolizing the order's mission. The scene is filled with dynamic figures, rich colors, and a powerful sense of divine intervention. The interplay of light and shadow, a hallmark of Baroque art, enhances the painting's theatricality and spiritual intensity. This work demonstrates Carreño's ability to orchestrate complex narratives with clarity and emotional force, drawing comparisons to the grand religious compositions of Peter Paul Rubens.

Another notable religious painting is his St. Sebastian Tended by St. Irene. This subject, popular during the Baroque period, allowed artists to combine religious piety with an appreciation for the human form. Carreño's interpretation is characterized by its tender pathos and elegant execution. The suffering saint is depicted with a refined naturalism, while the compassionate figures of St. Irene and her attendant are rendered with grace and sensitivity. The rich, dark palette, punctuated by highlights, creates a somber yet compelling mood.

Carreño also painted allegorical and mythological subjects, often for royal palaces. These works, while less numerous than his portraits and religious paintings, demonstrate his versatility and his familiarity with classical themes. His involvement in the fresco decorations of the Salón de los Espejos (Hall of Mirrors) in the Royal Alcázar of Madrid, working alongside Francisco Rizi and others, included mythological scenes that contributed to the splendor of this important state room. These frescoes, unfortunately, were lost in the fire that destroyed the Alcázar in 1734, but contemporary descriptions attest to their quality.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Collaborations

Juan Carreño de Miranda's artistic style is a complex synthesis of various influences, adapted and refined through his own unique sensibility. The towering presence of Diego Velázquez was an undeniable factor in the Madrid art scene. Carreño learned much from Velázquez's approach to portraiture, particularly the ability to capture a sitter's presence and psychology with unvarnished realism, yet always with a sense of decorum and dignity. However, Carreño's brushwork was often smoother, and his color palette could be warmer and more varied than Velázquez's later, more restricted tones.

The influence of Venetian art, particularly the work of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, was also profound. The Spanish royal collection was rich in Venetian masterpieces, and Carreño, like many of his contemporaries, studied them closely. This influence is evident in his rich use of color, his dynamic compositions, and his appreciation for luxurious textures. Anthony van Dyck's elegant and aristocratic portrait style, which had become a benchmark for courtly portraiture across Europe, also left its mark, particularly in the graceful poses and refined presentation of his sitters.

Carreño was not an isolated figure but an active participant in the artistic community of Madrid. His long-standing collaboration with Francisco Rizi was particularly significant. Together, they undertook numerous large-scale decorative projects, blending their individual strengths. Rizi's style was often more energetic and decorative, while Carreño brought a greater sense of gravity and psychological depth. Their partnership was instrumental in shaping the visual landscape of Madrid's churches and palaces during the mid-17th century.

He also interacted with other prominent artists of the Madrid School, such as Francisco de Herrera the Younger, known for his flamboyant style, and later, Claudio Coello, who would become a leading figure in the final phase of the Spanish Golden Age. The artistic environment was one of both competition and mutual influence. Carreño also had students, passing on his knowledge and techniques to the next generation. Among those associated with his workshop was José Jiménez Donoso, who also became a notable painter and architect.

A notable characteristic of Carreño's approach was his meticulousness and his dedication to his craft. An anecdote often recounted is his refusal of a knighthood offered by Charles II. When the King proposed to ennoble him by admitting him to the Order of Santiago (the same honor Velázquez had striven for and eventually received), Carreño is said to have humbly declined, stating that his painting itself was honor enough and that such titles might distract from his true calling. This story, whether entirely apocryphal or not, reflects an image of an artist deeply committed to his art above worldly ambitions.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Beyond the already mentioned Foundation of the Trinitarian Order and his royal portraits, several other works highlight Carreño's skill and versatility.

His Portrait of the Duke of Pastrana (c. 1670-1679) is a commanding example of his aristocratic portraiture. The Duke, clad in armor and holding a baton of command, exudes an air of authority and confidence. Carreño's attention to the reflective surfaces of the armor and the rich fabrics is exemplary. The composition is formal yet animated, capturing the sitter's individual character.

The Portrait of the Russian Ambassador Piotr Ivanovich Potemkin (1681-1682) is a fascinating work, documenting a diplomatic encounter. Potemkin, with his distinctive attire and stern expression, is rendered with an ethnographic precision that also conveys a powerful personality. This portrait demonstrates Carreño's ability to adapt his style to diverse sitters, moving beyond the familiar confines of the Spanish court.

In the realm of religious art, his depictions of the Immaculate Conception were numerous, a theme of particular importance in Counter-Reformation Spain. These paintings typically show the Virgin Mary, youthful and serene, surrounded by cherubs and celestial light, treading upon a crescent moon. Carreño's versions are characterized by their delicate beauty, soft colors, and a sense of ethereal grace, echoing the popular interpretations of this subject by artists like Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, though often with a more restrained and less overtly sentimental tone than his Sevillian contemporary.

His frescoes, though largely lost, were a significant part of his oeuvre. His work in the Atocha Church in Madrid and in the Cathedral of Toledo (specifically in the Ochavo chapel, again with Rizi) was highly praised. These projects required not only artistic skill but also considerable organizational ability to manage large surfaces and often complex iconographic programs.

The Madrid School and Contemporaries

Carreño de Miranda operated within a vibrant artistic ecosystem. The Madrid School of the 17th century was a powerhouse of talent. Besides Velázquez, who cast a long shadow, other significant figures included:

Francisco de Zurbarán: Known for his starkly realistic and deeply spiritual depictions of monks, saints, and still lifes, Zurbarán's influence was more prominent in the earlier part of Carreño's career.

Alonso Cano: A versatile artist active as a painter, sculptor, and architect, Cano's elegant and classical style offered a different sensibility. He also worked for the court and the church.

Jusepe de Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto): Though based in Naples, his powerful, often gritty, realism and dramatic use of chiaroscuro had a profound impact on Spanish painting, including in Madrid.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo: Primarily active in Seville, Murillo's softer, more sentimental style, especially in his religious paintings and genre scenes, gained immense popularity and provided a contrast to the more austere courtly style of Madrid.

Francisco Rizi: Carreño's frequent collaborator, Rizi was a key figure in the Madrid School, known for his dynamic compositions and skill in fresco.

Francisco de Herrera the Younger (el Mozo): Son of Francisco de Herrera the Elder (one of Velázquez's early teachers), "el Mozo" was known for a more flamboyant, almost proto-Rococo style, particularly in his later works.

Claudio Coello: A younger contemporary and sometimes rival, Coello is often considered the last great painter of the Spanish Golden Age. His masterpiece, The Adoration of the Sacred Host (La Sagrada Forma) in El Escorial, is a tour-de-force of illusionism and Baroque complexity.

Antonio de Pereda: Known for his rich still lifes, particularly vanitas paintings, and also for his religious and historical scenes, Pereda was another important member of the Madrid School.

Mateo Cerezo: A talented painter whose career was cut short, Cerezo produced works of notable quality, often influenced by Van Dyck and Titian, with a rich color sense.

Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo: Velázquez's son-in-law and successor as Court Painter before Carreño, Mazo was skilled in portraiture and landscape, often working in a style very close to his father-in-law.

Carreño's position within this group was one of consistent excellence and adaptability. He managed to absorb diverse influences without losing his individual voice, creating a body of work that was both representative of its time and personally distinctive.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Juan Carreño de Miranda continued to work actively into his later years, maintaining his position at court and fulfilling numerous commissions. His dedication to his art remained unwavering. He passed away in Madrid on October 3, 1685, at the age of 71, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant reputation.

His death marked the end of an era for the Madrid School. While talented painters like Claudio Coello continued to work, the extraordinary efflorescence of the Spanish Golden Age was drawing to a close, mirroring the political and economic fortunes of the Spanish Empire. The arrival of foreign artists, particularly French and Italian, in the 18th century under the new Bourbon dynasty would significantly alter the landscape of Spanish art.

Today, Carreño's works are held in major museums around the world, including the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, which houses an extensive collection of his paintings, the Louvre in Paris, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and numerous other public and private collections. His portraits of Charles II and Queen Mariana of Austria remain iconic images of the Spanish Habsburgs, offering invaluable historical and psychological insights. His religious paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, emotional depth, and adherence to the spiritual ideals of his time.

Juan Carreño de Miranda may not have achieved the revolutionary status of El Greco or the universal fame of Velázquez or Goya, but his contribution to Spanish art is undeniable. He was a master of his craft, a painter of great sensitivity and technical prowess who expertly navigated the demands of both church and state patronage. As a key figure in the Madrid School and the principal court painter after Velázquez, he played a crucial role in sustaining the brilliance of Spanish painting during the latter half of the 17th century. His art provides a vital window into the complex world of Golden Age Spain, its piety, its pageantry, and its poignant decline. He remains a testament to the enduring power of artistic dedication and skill.