Introduction: A Key Figure in Baroque Art

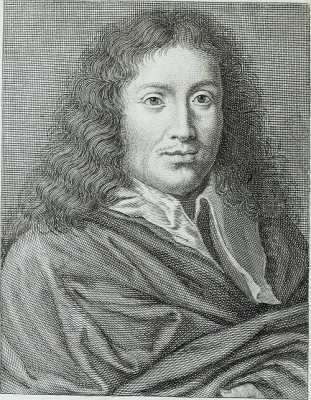

Ciro Ferri (1634-1689) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Italian Baroque art. Born and deceased in Rome, the very heart of the Baroque movement, Ferri dedicated his life to the creation of powerful and dynamic works primarily as a painter, but also demonstrating considerable skill as a sculptor and designer. His artistic journey is inextricably linked with that of his master, the celebrated Pietro da Cortona, whose style Ferri absorbed, perpetuated, and adapted. Operating predominantly within the vibrant artistic milieu of Rome, with notable periods of activity in Florence and Bergamo, Ferri contributed significantly to some of the most prestigious decorative projects of his time, leaving an indelible mark on the visual culture of the Seicento.

Ferri emerged during a period of intense artistic activity, following the groundbreaking innovations of artists like Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci, and contemporary with giants such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini who were reshaping Rome's architecture and sculpture. Within painting, the dominant trend was the High Baroque, characterized by its grandeur, illusionism, and emotional intensity, a style championed by Pietro da Cortona. It was into this legacy that Ciro Ferri stepped, becoming not just a follower, but a crucial conduit for the continuation of this powerful artistic language.

Early Life and Formative Years under Pietro da Cortona

Born in Rome in 1634, Ciro Ferri entered a world brimming with artistic fervor. Information suggests he came from a relatively affluent background; one account mentions his father bequeathing him a substantial sum of 40,000 scudi. However, this financial security did not deter him from pursuing a demanding career in the arts. His path was decisively shaped when he entered the bustling studio of Pietro da Cortona (1596-1669), arguably the leading painter of the Roman High Baroque alongside Andrea Sacchi, his main rival.

Becoming Cortona's principal pupil was a defining moment. Ferri proved to be an exceptionally adept and loyal student, quickly mastering his teacher's complex style, characterized by swirling compositions, luminous color palettes, and breathtaking illusionistic effects. He became Cortona's most trusted assistant and collaborator, working alongside his master on major commissions. This close working relationship meant that Ferri gained intimate, firsthand experience with the large-scale fresco projects that were the hallmark of Cortona's fame.

The master-student bond was profound. Ferri not only assisted Cortona during his lifetime but also became his artistic successor, entrusted with completing several important projects left unfinished upon Cortona's death in 1669. This inheritance cemented Ferri's position within the Roman art scene, positioning him as the primary bearer of the Cortonesque tradition, a style that emphasized dynamic movement, rich ornamentation, and a unified, often overwhelming, visual experience. His training provided him with the technical skills and stylistic vocabulary necessary to navigate the complex demands of patrons seeking magnificent decorations for their palaces and churches.

Major Roman Commissions: Decorating the Eternal City

Ferri's career unfolded primarily in Rome, where he contributed to several high-profile projects, often following in the footsteps of his master, Cortona. One of his earliest significant involvements was at the Quirinal Palace, the papal palace on the Quirinal Hill. Between 1656 and 1661, Ferri worked alongside Cortona on the decoration of the Gallery of Alexander VII. This extensive fresco cycle, depicting scenes from the life of Alexander the Great, was a major undertaking that showcased the High Baroque style's capacity for grand narrative and opulent display. Ferri's participation here honed his skills in large-scale fresco painting and collaborative work.

Perhaps Ferri's most prominent independent commission in Rome was the fresco decoration of the dome of the church of Sant'Agnese in Agone, located in the spectacular Piazza Navona. This church, primarily designed by Francesco Borromini and Girolamo Rainaldi, required a suitably dramatic culmination. Ferri painted the Glory of Paradise in the dome, a swirling vortex of saints and angels ascending towards divine light, a theme perfectly suited to the Baroque sensibility. This work, undertaken later in his career, demonstrated his ability to handle vast, complex compositions independently, solidifying his reputation as a leading master of fresco.

Ferri was also involved in work at the epicenter of the Catholic world, St. Peter's Basilica. While details suggest involvement in restoration efforts, he is specifically credited with providing designs for mosaics, including some intended for the right wing of the basilica. Working within St. Peter's, amidst the ongoing contributions of artists like Bernini, placed Ferri at the highest level of ecclesiastical patronage. His ability to design for mosaic, a demanding and prestigious medium, further highlights his versatility.

His Roman activities extended to other significant churches. He created frescoes for San Marco, a basilica adjacent to the Palazzo Venezia. He also worked in Sant'Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso (likely the "Marso" mentioned in source material), a church favored by the Lombard community in Rome. Furthermore, a painting of S. Francesco located in the church of Santa Maria del Suffragio on Via Giulia has been attributed to him, although some stylistic discussion surrounds it. These commissions demonstrate his consistent engagement with religious institutions across the city.

Florentine Achievements and Work Beyond Rome

While Rome was his primary base, Ciro Ferri's talents were also sought in Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance, which still maintained significant artistic patronage, particularly from the powerful Medici family. His most important Florentine commission was the completion of the fresco decorations in the Pitti Palace, the grand ducal residence of the Medici. Pietro da Cortona had begun an ambitious cycle decorating the ceilings of the state rooms, known as the Planetary Rooms, but left the work unfinished.

Ferri was called upon to continue this prestigious project, painting the ceilings of the Apollo and Saturn rooms, seamlessly matching Cortona's style to create a unified decorative scheme. These frescoes, depicting complex allegories related to Medici virtues and rule, are prime examples of High Baroque ceiling painting, characterized by quadratura (illusionistic architecture) and di sotto in sù (figures seen from below). His successful completion of the Pitti Palace frescoes affirmed his status as Cortona's true artistic heir and demonstrated his ability to satisfy the demands of elite patrons like the Grand Dukes of Tuscany.

His work also took him north to Bergamo in Lombardy. In 1665, Ferri traveled there to execute frescoes in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, a major medieval church undergoing Baroque updates. This commission outside the main centers of Rome and Florence indicates the reach of his reputation. The specific subjects of these frescoes contribute to the rich layering of art within this important basilica.

Beyond specific commissions, Ferri's connection to Florence was strengthened by his role in artistic education. In 1673, he was appointed director or president of the newly established Florentine Academy in Rome (Accademia dei Fiorentini a Roma), an institution founded under the patronage of Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici to train Florentine artists in the Roman style. This prestigious appointment underscored his standing not only as an artist but also as a respected teacher and figure of authority within the Italo-Florentine artistic community.

Artistic Style: The Language of the High Baroque

Ciro Ferri's artistic style is firmly rooted in the High Baroque, as defined and practiced by his master, Pietro da Cortona. His works are characterized by dynamic compositions, often featuring swirling masses of figures caught in dramatic movement. He employed rich, warm colors and strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to enhance the emotional intensity and three-dimensionality of his scenes. Illusionism was a key element, particularly in his ceiling frescoes, where painted architecture blends with figural scenes to create seemingly boundless spaces opening up above the viewer.

While deeply indebted to Cortona, some contemporary and later critics noted subtle differences. Ferri's style is sometimes described as slightly less energetic or graceful than his master's, perhaps with a harder edge or a less vibrant palette in certain works. However, these are nuanced distinctions; Ferri remained a highly skilled practitioner of the Cortonesque manner, capable of producing works of great complexity and visual impact. His commitment to Cortona's principles ensured the continuation of this particular strain of the Baroque well into the later decades of the 17th century.

His proficiency extended beyond large-scale frescoes. Ferri was an accomplished draftsman, producing numerous preparatory drawings and sketches that reveal his working process. These drawings often exhibit great fluidity and energy. He also created designs for other media, including the aforementioned mosaics for St. Peter's and designs for tapestries. His collaboration with the sculptor Pietro Lucatelli on tapestry cartoons for the Barberini family demonstrates his engagement with the decorative arts and the Baroque ideal of integrating various art forms.

His subject matter predominantly drew from religious and mythological or historical narratives, typical of the era's major commissions. Works like The Miracle of Saint Zenobius, depicting the Florentine saint reviving a youth (a painting noted to have entered the Pitti Palace collection in 1665, possibly commissioned by the Medici), showcase his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with narrative clarity and emotional resonance. Similarly, Joseph Turning Away from Potiphar's Wife captures a moment of dramatic tension and moral choice. Even works whose attribution has been debated, like the Sacrifice of Solomon, engage with grand historical themes favored by Baroque patrons.

Teacher, Academician, and Competitor

Ciro Ferri was more than just a prolific artist; he played an active role in the institutional art world of his time. His membership in the prestigious Accademia di San Luca in Rome, the city's primary guild and academy for artists, placed him within the established hierarchy. His influence extended through his teaching activities, both within his own studio and through his leadership role at the Accademia dei Fiorentini in Florence (operating in Rome). He was known for nurturing the talents of younger artists, thus contributing to the dissemination of the High Baroque style.

The art world of 17th-century Rome was highly competitive. Ferri vied for commissions and prestige alongside other prominent painters. Key rivals included Carlo Maratti (1625-1713), who represented a more classicizing trend within the Baroque, often seen as an alternative to the exuberant style of Cortona and Ferri. Another significant contemporary was Giovanni Battista Gaulli, known as Baciccio (1639-1709), famed for his spectacular ceiling frescoes at the Church of the Gesù, which pushed illusionism to new heights, influenced by Bernini. The competition among these artists, and others like Giacinto Brandi or Luca Giordano (who worked across Italy), fueled innovation but also created professional tensions.

Ferri navigated the complex system of patronage, working for powerful families like the Medici in Florence and the Barberini in Rome. His relationship with Cardinal Francesco Barberini, a major patron of the arts, highlights the dynamics involved. While Barberini employed Ferri, records indicate the Cardinal sometimes expressed impatience with the artist's perceived slowness in completing work. This anecdote reveals the pressures artists faced in meeting the expectations of demanding and influential clients. Ferri's ability to secure and maintain such high-level patronage despite these challenges speaks to the desirability of his skills.

His collaborations, particularly the documented work with Pietro Lucatelli on tapestry designs for the Barberini, illustrate the interconnected nature of artistic production. Large workshops and collaborative projects involving painters, sculptors, architects (like Borromini or Rainaldi at Sant'Agnese), and craftsmen were common, especially for extensive decorative schemes. Ferri operated successfully within this system, leveraging his skills across different aspects of design and execution. His influence can be seen in the work of later Baroque artists who continued to explore dynamic compositions and rich color, such as Francesco Solimena in Naples.

Later Years and Legacy

Ciro Ferri remained active in the later part of his life, continuing to produce drawings and designs even as large-scale fresco commissions might have become less frequent or were completed by his workshop. He continued to be a respected figure in the Roman art scene until his death in Rome in 1689. He passed away at the height of the Baroque era, a period whose visual language he had significantly helped to shape and sustain.

His legacy lies primarily in his role as the most faithful and capable successor to Pietro da Cortona. Through his completion of Cortona's projects, particularly in the Pitti Palace, and his own independent works like the Sant'Agnese dome, Ferri ensured the vitality of the High Baroque decorative style. He demonstrated that Cortona's approach was not merely personal but a transmissible language capable of creating breathtaking environments of paint and plaster.

While sometimes overshadowed by the towering figures of Cortona or Bernini, or compared to the distinct classicism of Maratti or the dramatic intensity of Baciccio, Ferri holds a crucial place in the history of Baroque art. He was a master technician, a skilled composer of complex scenes, and a vital link in the transmission of the High Baroque aesthetic. His works in Rome, Florence, and Bergamo remain important testaments to the grandeur and dynamism that characterized Italian art in the Seicento. His influence extended through his students and his leadership roles in academies, contributing to the artistic fabric of his time.

Conclusion: A Master of the High Baroque Idiom

Ciro Ferri navigated the demanding art world of 17th-century Italy with considerable success. As Pietro da Cortona's chief disciple and artistic heir, he absorbed the lessons of the High Baroque and applied them with skill and dedication across painting, sculpture, and design. His contributions to major decorative cycles in the Quirinal Palace, the Pitti Palace, and Sant'Agnese in Agone cemented his reputation and ensured the continuation of a powerful, illusionistic, and emotionally charged artistic style.

Working alongside and sometimes in competition with artists like Carlo Maratti and Baciccio, and under the patronage of powerful families and institutions, Ferri carved out a significant career. His versatility is evident in his frescoes, easel paintings, mosaic designs, and tapestry cartoons. Furthermore, his roles as a teacher and academician underscore his importance within the artistic community of his time. Though perhaps lacking the ultimate spark of innovative genius attributed to Cortona or Bernini, Ciro Ferri remains an indispensable figure for understanding the richness and complexity of Roman and Florentine Baroque art, a master craftsman who expertly wielded the visual language of his era. His works continue to impress viewers with their scale, dynamism, and decorative splendor.