Daniel Ridgway Knight stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century art, an American painter who found his voice and greatest success depicting the rustic charm of French peasant life. Born in Philadelphia but spending the majority of his prolific career in France, Knight became renowned for his sun-drenched canvases featuring young women in idyllic garden settings or engaged in daily tasks along riverbanks. His work skillfully blended academic precision with the burgeoning influences of Realism and Impressionism, capturing a nostalgic vision of rural existence that resonated deeply with audiences on both sides of the Atlantic.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Philadelphia

Daniel Ridgway Knight entered the world on March 15, 1839, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Raised in a family with Quaker roots, his path towards an artistic career began relatively early. His formal training commenced at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), an institution that served as a crucible for many prominent American artists. It was here that Knight's foundational skills were honed, and significantly, where he studied alongside individuals who would also achieve great fame.

Among his classmates at PAFA were Mary Cassatt, who would become a leading figure associated with the Impressionist movement, particularly known for her sensitive portrayals of mothers and children, and Thomas Eakins, destined to be one of America's foremost Realist painters, celebrated for his uncompromising depictions of modern life, portraiture, and scientific observation. This period provided Knight with a solid grounding in drawing and painting, exposing him to the academic traditions prevalent at the time while fostering connections within a burgeoning American art scene.

Parisian Training: The Lure of the École des Beaux-Arts

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Knight recognized the necessity of further study in Europe, particularly in Paris, then the undisputed center of the art world. He made the journey across the Atlantic, eager to immerse himself in the rigorous training offered by the French system. In 1861, he enrolled in the atelier of Charles Gleyre, a Swiss-born painter working in Paris known for his academic style and for teaching several students who would later become key Impressionists, including Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Knight's Parisian education continued at the venerable École des Beaux-Arts, the official bastion of French academic art. There, he further refined his technique under the tutelage of Alexandre Cabanel, a highly successful and influential academic painter. Cabanel was celebrated for his historical, classical, and religious subjects, executed with smooth finishes and idealized forms, epitomizing the official taste favored by the Paris Salon. This training instilled in Knight a deep respect for draftsmanship, composition, and the careful rendering of the human form, elements that would remain visible throughout his career, even as he embraced other influences.

A Brief Return: The American Civil War

Knight's studies in Paris were interrupted by the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1865). Compelled by duty, he returned to the United States in 1863 to enlist in the Union Army. He served with the Pennsylvania Volunteers, specifically in the emergency militias formed during critical periods of the conflict. While his military service was relatively brief, it marked a significant interlude in his artistic development.

Interestingly, Knight utilized his artistic skills during this period. He is known to have created sketches documenting military life, capturing the likenesses of fellow soldiers and the atmosphere of the camps and battlefields. These drawings served not only as personal records but also contributed to the visual documentation of the war, offering glimpses into the daily realities faced by those involved. Following the conclusion of the war, Knight resumed his artistic pursuits, his experiences perhaps adding a layer of maturity to his perspective.

Settling in France: Finding His Muse

After the Civil War and a period back in Philadelphia where he married Rebecca Morris Webster in 1871, Knight made the pivotal decision to return to France in 1872. This move would prove permanent and define the trajectory of his career. He and his family settled initially near Paris, eventually establishing a home and studio in Poissy, a town on the Seine River west of the capital. It was here, amidst the picturesque landscapes and rural communities of the French countryside, that Knight found his true artistic calling.

He became deeply engaged with depicting the local environment and its inhabitants, particularly the peasant women engaged in their daily routines. The gardens, fields, and riverbanks of the Seine valley became his open-air studio. Unlike the often harsh realities portrayed by some Realists like Jean-François Millet, Knight's vision tended towards the idyllic and picturesque, focusing on the quiet dignity and simple beauty of rural life. This focus would bring him considerable fame and commercial success.

Artistic Style: Realism Tempered with Idealism

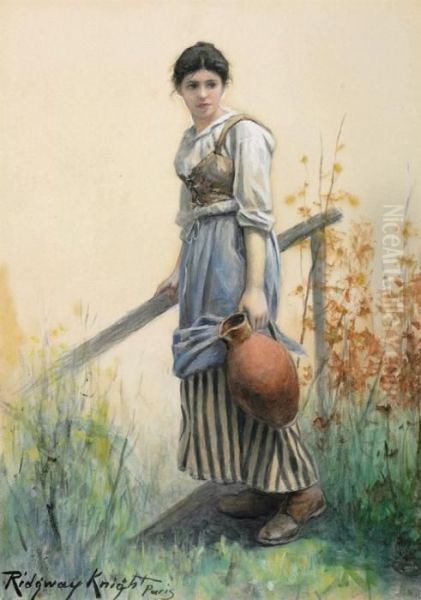

Daniel Ridgway Knight is primarily classified as a Realist painter, yet his work possesses a distinct character that sets it apart. His commitment to Realism is evident in the meticulous attention he paid to detail – the textures of fabrics, the specific varieties of flowers in a garden, the play of light on water, and the accurate rendering of his figures' features and postures. He aimed for a high degree of verisimilitude, grounding his scenes in careful observation of the natural world.

However, Knight's Realism was often softened by a certain idealism and a picturesque sensibility. His peasant women, while depicted performing tasks like washing clothes, tending gardens, or gathering flowers, are typically portrayed as young, healthy, and comely. The settings are invariably pleasant, bathed in soft, natural light, evoking a sense of tranquility and harmony rather than the backbreaking labor often associated with peasant life. This approach aligned with a popular taste for charming, non-confrontational rural scenes among bourgeois collectors in both Europe and America.

The Influence of Naturalism and Plein Air Painting

Knight worked during a period when Naturalism, an artistic movement closely related to Realism but often emphasizing a more objective, almost scientific observation of rural subjects and landscapes, was gaining prominence. Artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret were key figures in this movement in France. Knight shared with the Naturalists a dedication to painting outdoors (en plein air) to capture the authentic effects of natural light and atmosphere.

His commitment to plein air painting was exceptional. To overcome the challenges of inclement weather, particularly during the colder months, Knight constructed a unique studio in his garden at Poissy. Made largely of glass, this structure allowed him to paint his models outdoors, benefiting from natural light year-round, while being sheltered from the elements. This innovative approach enabled him to achieve the luminous, sun-dappled effects that became a hallmark of his style, particularly the interplay of light and shadow on figures and foliage.

Impressionism's Subtle Touch

While fundamentally a Realist with strong academic training, Knight was not immune to the revolutionary changes brought about by Impressionism, which flourished during his time in France. He was acquainted with several key Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, who also found inspiration in the landscapes along the Seine. Although Knight never adopted the broken brushwork or dissolved forms characteristic of core Impressionism, its influence can be detected in his work.

This influence is most apparent in his heightened sensitivity to light and color. His palette often became brighter and more vibrant than typical academic painting, and his handling of sunlight, particularly the way it filters through leaves or reflects off water, shows an awareness of Impressionist concerns. He masterfully captured specific times of day and atmospheric conditions, lending his scenes a sense of immediacy and freshness, even within his detailed, realistic framework. He successfully integrated aspects of the Impressionist observation of light without sacrificing the clarity and finish valued by the Salon.

Signature Subject: The Peasant Woman in Nature

The theme that came to define Daniel Ridgway Knight's oeuvre was the depiction of French peasant women, usually solitary figures or small groups, situated within lush natural settings. These women are often shown in moments of quiet contemplation or gentle activity: tending flowers in vibrant gardens, pausing during a harvest, chatting by a riverside, or, famously, waiting for a ferry. His paintings frequently emphasize the harmonious relationship between the figures and their environment.

Works like Hailing the Ferry (1888), perhaps his most famous painting, encapsulate this theme. It depicts two young women on a sunlit riverbank, one raising her hand to signal a ferryman across the water. The scene is imbued with a sense of peaceful anticipation, rendered with meticulous detail and bathed in the warm glow of the afternoon sun. Other paintings, such as Washing Day or titles featuring gardens like A Garden above the Seine at Rolleboise, similarly focus on idealized female figures integrated into beautifully rendered natural landscapes. These images presented a romanticized view of rural life that held great appeal.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Beyond Hailing the Ferry, Knight produced a large body of work centered on similar themes. Washing Day (Les Laveuses) depicts women laundering clothes by the river, a common chore transformed into a picturesque scene through Knight's handling of light and composition. Farm Hands at Noontide explores a slightly different aspect of rural life, showing laborers taking a midday break, showcasing his ability to handle group compositions and genre scenes.

His garden paintings are particularly celebrated. Often featuring his own meticulously cultivated garden at Poissy, these works burst with color and detail, showcasing a profusion of flowers like roses, hollyhocks, and chrysanthemums. The female figures within these gardens often seem almost extensions of the natural beauty surrounding them, embodying innocence and grace. Throughout these works, Knight's technical skill in rendering textures – the softness of petals, the roughness of stone walls, the shimmer of water – is consistently evident.

The Innovative Glass Studio

Knight's dedication to capturing authentic outdoor light led him to create his well-known glass house studio. This structure was essentially a mobile greenhouse on rails, allowing him to position it optimally in his garden according to the light conditions he desired. Inside, he could pose his models and set up his easel, effectively painting outdoors while protected from wind, rain, or cold.

This innovation was crucial to his working method and the resulting aesthetic of his paintings. It allowed him the time and comfort needed to execute his highly detailed canvases directly from life, capturing the subtle nuances of natural illumination over extended periods. This commitment to direct observation, facilitated by his unique studio, contributed significantly to the convincing realism and luminous quality that characterized his most successful works and set him apart from studio-bound academic painters.

Recognition, Awards, and Success

Daniel Ridgway Knight achieved considerable recognition and success during his lifetime. He exhibited regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official annual art exhibition, and garnered several awards. He received a Third Class Medal at the Salon of 1888 (likely for Hailing the Ferry), a Silver Medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) of 1889, and a Gold Medal at the Munich International Exposition in 1890.

Further honors cemented his reputation. He was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor, France's highest order of merit, in 1889, a significant acknowledgment for a foreign artist. He also received the Knight's Cross of the Royal Order of Saint Michael of Bavaria in 1893. His paintings were highly sought after by collectors in both France and the United States, commanding high prices and ensuring his financial security. His work appealed to a taste for beautifully executed, easily understandable, and emotionally pleasant subjects.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Knight operated within a rich and diverse artistic landscape. His early association with Mary Cassatt and Thomas Eakins at PAFA placed him among the foundational figures of modern American art. In France, his teachers Gleyre and Cabanel represented the powerful academic tradition he absorbed and adapted. His awareness of and interaction with Impressionists like Monet, Renoir, and Sisley demonstrate his engagement with the avant-garde, even if he charted his own course.

His chosen genre, the depiction of peasant life, connected him to a lineage of French artists including the Barbizon School painter Jean-François Millet, known for his more somber and monumental portrayals of rural labor, and Jules Breton, who also painted idealized scenes of peasant women. Knight's specific focus on sunlit, picturesque scenes aligns him closely with other successful Salon painters of the era who specialized in similar themes, such as Léon Lhermitte and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, forming part of a broader European trend in Naturalist and Realist genre painting.

Family Life and Artistic Legacy

Daniel Ridgway Knight's personal life was intertwined with his art. His marriage to Rebecca Morris Webster provided a stable domestic foundation for his career abroad. The couple had three sons. Notably, one of his sons, Louis Aston Knight (often referred to as Aston Knight, though sometimes cited by his given names Charles Emison Knight), followed in his father's footsteps and became a successful landscape painter in his own right. Aston Knight often painted similar locations along the Seine but developed his own distinct style, particularly known for his vibrant water reflections.

Daniel Ridgway Knight faced personal losses, including the deaths of his father in 1873 and his mother in 1879. Despite these challenges, he maintained a remarkably consistent and productive career, working diligently into his later years. He continued to paint his beloved French countryside and its inhabitants until his death in Paris on March 9, 1924, just shy of his 85th birthday.

Later Years and Enduring Reputation

In his later years, some accounts suggest Knight's work may have taken on slightly more introspective or atmospheric qualities, perhaps moving subtly away from the bright sunshine of his peak period, though his core themes remained consistent. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical proficiency and charming subject matter.

While artistic tastes shifted dramatically in the early 20th century with the rise of Modernism, Knight's paintings have retained their appeal, particularly among collectors who value traditional craftsmanship and picturesque beauty. Academically, he is recognized as a key figure among American expatriate artists in France, representing a successful fusion of American artistic sensibility with European training and themes. His work provides valuable insight into the tastes and artistic currents of the late 19th century, particularly the widespread fascination with idealized rural life.

Conclusion: An American Eye on French Soil

Daniel Ridgway Knight carved a unique niche for himself in the art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An American by birth and early training, he became one of the most successful painters of French rural life, adopting France as his home and primary source of inspiration. His meticulous technique, honed through academic study, combined with a sensitivity to light influenced by plein air practice and Impressionism, resulted in works of enduring charm and beauty. His idealized depictions of peasant women in sunlit landscapes captured a nostalgic vision that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continues to find admirers today. Knight remains a testament to the rich cross-cultural exchanges that shaped American art during a pivotal era.