David Loggan (1635-1692) stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of 17th-century British art, renowned particularly for his meticulous engravings and detailed bird's-eye views of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Born in Danzig (Gdańsk), then part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth but with a significant German-speaking population and strong Hanseatic ties, Loggan's mixed heritage—his father was Scottish and his mother English—likely contributed to his cosmopolitan outlook and eventual migration. His contributions extend beyond mere topographical records; they are invaluable historical documents, artistic achievements, and a testament to the burgeoning print culture of Stuart England. This exploration delves into his life, his seminal works, his artistic style, his contemporaries, and his enduring legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Apprenticeship

David Loggan's journey into the world of art began in his birthplace of Danzig. While concrete details of his earliest training are somewhat scarce, it is widely believed that he received his initial instruction in the art of engraving in Denmark. The artistic currents of Northern Europe were rich and varied, with a strong tradition in printmaking, and Loggan would have been exposed to these influences from a young age.

His formal artistic education took a significant step forward when he moved to the Netherlands. There, he became a pupil of Willem Hondius (c. 1598–c. 1658) in Amsterdam. Hondius was a respected engraver and cartographer, himself part of a larger artistic dynasty, the Hondius family, famous for their maps and atlases, including Jodocus Hondius and Hendrik Hondius. Under Willem Hondius's tutelage, Loggan would have honed his skills in line engraving, a demanding technique requiring precision, a steady hand, and a keen eye for detail. The Dutch Golden Age was at its zenith, and Amsterdam was a bustling hub of artistic production and international trade, providing a fertile environment for an aspiring artist. The Dutch emphasis on realism, detailed observation, and technical mastery in printmaking undoubtedly left an indelible mark on Loggan's developing style.

Arrival in England and Early Career in London

Around 1653, at the age of approximately eighteen, David Loggan made the pivotal decision to move to England. This was a period of significant political and social upheaval, with England then under the Commonwealth Protectorate led by Oliver Cromwell. Despite the somewhat austere cultural climate compared to the Royalist era, London remained a centre of artistic patronage and opportunity, particularly for skilled craftsmen like engravers.

Upon his arrival, Loggan initially settled in London. He quickly began to establish himself, undertaking various commissions. His skills were versatile, encompassing not only topographical and architectural engravings but also portraiture. In these early years, he produced a number of engraved portraits of notable figures, a genre that was highly popular. He also created frontispieces and illustrations for books, a burgeoning market that provided steady work for engravers. His meticulous technique and ability to capture a likeness or render complex architectural details with clarity soon brought him to the attention of patrons and publishers. This period in London was crucial for building his reputation and network, laying the groundwork for the more ambitious projects that would define his career. He would have been aware of, and likely interacted with, other artists and engravers active in London at the time, such as William Faithorne the Elder (c. 1616–1691), a prominent English engraver and portraitist, and the prolific Bohemian-born Wenceslaus Hollar (1607–1677), whose topographical prints and cityscapes set a high standard.

The Oxford Years: Oxonia Illustrata

A defining chapter in David Loggan's career began with his association with the University of Oxford. He moved to Oxford, and his exceptional talent for architectural rendering led to his appointment as "publicus Academiae sculptor" (University Engraver or Engraver to the University) in 1669. This prestigious position came with the responsibility of producing official engravings for the university, a role that perfectly suited his meticulous skills.

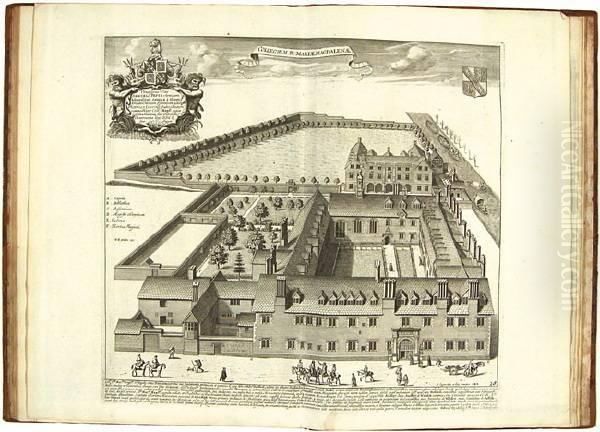

His most significant achievement during this period, and arguably of his entire career, was the monumental work Oxonia Illustrata, published in 1675. This lavish volume comprised a series of forty copperplate engravings, primarily bird's-eye views of the Oxford colleges, halls, the Bodleian Library, the Sheldonian Theatre, and other significant university buildings. Each plate was a testament to Loggan's painstaking accuracy, his ability to convey a sense of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, and his artistic sensibility in composing these complex scenes. The views were not merely architectural plans but vibrant depictions, often including figures of students, dons, and townspeople, adding life and scale to the scenes.

Oxonia Illustrata was more than just a collection of beautiful pictures; it was a statement of Oxford's grandeur and intellectual prowess, particularly significant in the Restoration period as institutions sought to reassert their historical importance. The work provided an unparalleled visual record of the university's architecture at a specific moment in time, capturing buildings that have since been altered or demolished. The level of detail, from the intricacies of Gothic tracery to the layout of formal gardens, was extraordinary. This project required immense dedication, involving detailed surveys, numerous preparatory drawings, and the laborious process of engraving the large copper plates. The publication was a commercial success and cemented Loggan's reputation as the foremost architectural engraver of his day. It also served as an important model for subsequent topographical publications.

Cambridge and Cantabrigia Illustrata

Following the resounding success of Oxonia Illustrata, it was a natural progression for Loggan to undertake a similar project for England's other ancient university, Cambridge. He embarked on this ambitious task, and in 1690, Cantabrigia Illustrata was published. This volume, similar in format and style to its Oxford counterpart, featured around thirty engraved plates showcasing the colleges, public buildings, and overall layout of the University of Cambridge.

Like the Oxford series, Cantabrigia Illustrata provided meticulously detailed bird's-eye views, capturing the unique architectural character of each Cambridge college, its courts, chapels, and gardens. Loggan applied the same rigorous approach to accuracy and artistic composition, resulting in a work of comparable historical and aesthetic value. These engravings offer invaluable insights into the appearance of Cambridge at the close of the 17th century, documenting its architectural heritage with unparalleled precision.

The production of Cantabrigia Illustrata further solidified Loggan's status as the pre-eminent chronicler of English academic institutions. Together, these two volumes represent a monumental achievement in the history of printmaking and architectural illustration. They not only provided contemporary audiences with stunning visual representations of these revered seats of learning but also created an enduring legacy for future historians, architects, and art lovers. The dedication required to complete such comprehensive surveys and the artistic skill to translate them into such fine engravings underscore Loggan's mastery of his craft. These works were not just illustrative; they were celebratory, reflecting the pride and prestige associated with Oxford and Cambridge.

Loggan's Artistic Style and Techniques

David Loggan's artistic style is characterized by its remarkable precision, clarity, and meticulous attention to detail. His primary medium for his major architectural works was line engraving on copperplate, a technique that allowed for fine lines and rich tonal variations through hatching and cross-hatching.

A hallmark of his university views is the bird's-eye perspective. This elevated viewpoint allowed him to depict entire college complexes, showing the relationship between buildings, courtyards, and gardens in a comprehensive manner that would be impossible from ground level. This was not a simple aerial view but a carefully constructed perspective, often combining elements of axonometric projection with artistic adjustments to ensure clarity and visual appeal. He managed to convey both the overall layout and specific architectural features with astonishing accuracy.

Loggan's draughtsmanship was exceptional. The preparatory drawings for his engravings (many of which survive) demonstrate his careful observation and skilled hand. When translating these drawings to the copper plate, he maintained a high level of fidelity. His rendering of architectural textures—stone, brick, lead roofs, glass—was highly effective. He also paid close attention to the play of light and shadow, which gave his engravings a sense of depth and solidity. The inclusion of small figures, often engaged in academic or leisurely pursuits, not only added visual interest and a sense of scale but also provided glimpses into university life of the period.

Beyond his architectural engravings, Loggan was also a skilled portraitist, particularly in the medium of plumbago (graphite) on vellum or parchment. These miniature portraits were highly sought after for their delicate execution and ability to capture a sitter's likeness. His engraved portraits, often used as frontispieces for books, also demonstrate his skill in rendering human features and character, though they are perhaps overshadowed by the grandeur of his architectural works. His style in portraiture was in line with contemporaries like William Faithorne the Elder, though Loggan's plumbago work had a particular finesse.

Portraiture and Other Commissions

While David Loggan is most celebrated for Oxonia Illustrata and Cantabrigia Illustrata, his artistic output was diverse and included a significant body of portraiture and other commissioned works. Throughout his career, he was sought after for his skill in capturing likenesses, both in engraved form for publication and as intimate plumbago (graphite) drawings on vellum.

His engraved portraits often served as frontispieces for books, depicting authors, scholars, and prominent public figures. These portraits, while adhering to the conventions of the time, showcase his ability to convey character and status through careful attention to facial features, attire, and symbolic attributes. He engraved portraits of figures such as King Charles II, James, Duke of York (later James II), and various bishops and nobles. These works placed him firmly within the tradition of portrait engravers like his contemporary Robert White (c. 1645–1703), who, in fact, is believed to have been a pupil of Loggan, particularly in the art of graphite portraiture.

Loggan also produced title pages and illustrations for a variety of publications. A notable example is the frontispiece he designed and engraved for the 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer. Such commissions required not only technical skill but also an understanding of allegorical representation and typographic layout. He also created a frontispiece for The Catholique Planispaire. These works demonstrate his versatility and his engagement with the broader print market of the time. His ability to work across different genres—from grand architectural surveys to detailed individual portraits and intricate book illustrations—highlights the breadth of his talent and his adaptability to the demands of various patrons and publishers. The demand for such works was high, and Loggan's skill ensured he was a key contributor to the visual culture of Restoration England.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

David Loggan operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic milieu in 17th-century England. His career intersected with, and was influenced by, a number of significant artists, engravers, and publishers.

His master, Willem Hondius, connected him to the rich Dutch printmaking tradition. In England, Wenceslaus Hollar was a towering figure whose prolific output of topographical views, costume studies, and natural history subjects set a high benchmark. Loggan and Hollar were contemporaries, and there is evidence of Hollar's influence on Loggan's approach to detailed representation, and they are known to have collaborated on some projects, particularly botanical and zoological illustrations.

William Faithorne the Elder was another leading English engraver, particularly renowned for his portraits, which often possessed a psychological depth. Loggan and Faithorne would have been aware of each other's work in the competitive London print market. Loggan's own pupil, Robert White, became a highly successful portrait engraver in his own right, carrying forward his master's skill in capturing likenesses, especially in graphite.

Other engravers active during this period included Abraham Blooteling (1640-1690), a Dutch engraver who spent time in England and was known for his mezzotints and line engravings, and Michael Burghers (c. 1647/8–1727), who was also active in Oxford, sometimes seen as Loggan's successor there for a period, engraving almanacs and illustrations. The publisher Pieter van der Aa (1659-1733) in Leiden later used Loggan's views in his own publications, sometimes without full attribution, highlighting the international circulation and influence of Loggan's work.

In the broader artistic scene, portrait painters like Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680) and later Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) dominated the field of oil portraiture. While Loggan was not primarily an oil painter, the demand for engraved versions of their portraits meant that engravers were crucial in disseminating these images to a wider audience. Loggan's work, therefore, was part of a larger ecosystem of artistic production and dissemination. The cartographer and publisher John Ogilby (1600-1676), known for his ambitious illustrated atlases and road maps (like Britannia), was another contemporary involved in large-scale print projects that shared some similarities in scope and ambition with Loggan's university views. The work of earlier engravers like members of the Van de Passe family (Crispijn van de Passe the Elder and his children, including Simon and Magdalena van de Passe), who had worked in England, also formed part of the heritage upon which Loggan and his contemporaries built.

Personal Life and Later Years

Details about David Loggan's personal life, beyond his professional achievements, are somewhat less documented, as is common for many artists of his era whose fame rests primarily on their work. We know that he married Anna Jordan, daughter of a Justice of the Peace from Witney, Oxfordshire, in 1662. This marriage likely helped solidify his connections within English society. They are known to have had at least one son, John Loggan, who also became an engraver, though he did not achieve the same level of prominence as his father.

A significant event in his personal life was his relocation from London. In 1665, during the Great Plague of London, Loggan moved his family to Nuffield, near Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire. This move, prompted by a desire to escape the pestilence ravaging the capital, also brought him closer to Oxford, which would soon become the primary focus of his artistic endeavors. His subsequent appointment as University Engraver in 1669 and his residency in Oxford for many years were pivotal.

After the completion of Cantabrigia Illustrata in 1690, Loggan appears to have returned to London. He continued to work, though perhaps on less monumental projects. His dedication to his craft remained throughout his life. David Loggan passed away in London in the summer of 1692, likely in August, and was buried at the church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate. He left behind a legacy of meticulously crafted artworks that continue to be admired for their beauty and historical significance.

The Accuracy and Reception of Loggan's Work

David Loggan's works, particularly Oxonia Illustrata and Cantabrigia Illustrata, were highly acclaimed in his own time and have largely maintained their reputation for accuracy and detail. Contemporaries lauded the precision of his architectural renderings and the comprehensive nature of his surveys. These volumes were seen not only as artistic achievements but also as valuable records of the universities' physical fabric.

However, modern scholarship, while generally affirming the high degree of accuracy, has also noted that Loggan, like many topographical artists of his era, occasionally employed a degree of artistic license. This might involve slight idealizations of certain features, minor adjustments in perspective for compositional clarity, or the depiction of formal garden layouts that might have been planned but not fully realized, or perhaps presented in a more geometrically perfect state than they were in reality. For instance, some debate has occurred regarding the exactness of the geometric patterning in his depictions of certain botanical gardens.

These minor idealizations do not significantly detract from the overall historical value of his work. They were often conventional practices aimed at presenting the subject in its best possible light or achieving a more harmonious and impressive visual effect. The primary purpose was to create a "true and lively representation," and in this, Loggan excelled. His views were intended to be both informative and celebratory.

The reception of his work was overwhelmingly positive. The university volumes were prestigious publications, subscribed to by colleges, dignitaries, and wealthy individuals. They served as important tools for promoting the image and status of Oxford and Cambridge both domestically and internationally. The plates were frequently copied and adapted by later engravers and publishers, sometimes for decades, attesting to their enduring appeal and authority. Even today, Loggan's engravings are indispensable resources for architectural historians studying the 17th-century university, and for anyone seeking to visualize the academic world of Stuart England.

Modern Scholarship and Enduring Influence

In the centuries since his death, David Loggan's work has continued to attract the attention of scholars, collectors, and art enthusiasts. Modern research has further illuminated his techniques, the context of his commissions, and the significance of his contributions to British art and topography.

His university views, Oxonia Illustrata and Cantabrigia Illustrata, are prized by libraries and collections worldwide, including the British Library, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and the Wellcome Collection. These institutions not only preserve his original engravings and, in some cases, preparatory drawings, but also facilitate their study. Scholars have analyzed his working methods, comparing his engravings with surviving buildings and contemporary documents to assess their accuracy and the artistic choices he made. His work is considered a prime example of early scientific illustration in an architectural context, and Oxonia Illustrata has been noted as a rare early example of a purely illustrated book printed with a rolling press.

Loggan's influence extended to subsequent generations of artists and illustrators. His pupil, Robert White, became a distinguished engraver. Later topographical artists often looked to Loggan's work as a model for its comprehensiveness and clarity. In the early 20th century, the artist Edmund Hort New (1871–1931) was so inspired by Loggan's Oxford views that he undertook a project to re-draw many of the Oxford colleges in a similar bird's-eye style, consciously emulating Loggan's approach. These became known as the "New Loggan Prints" and enjoyed considerable popularity, demonstrating the timeless appeal of Loggan's original vision.

Furthermore, Loggan's engravings continue to be used as primary source material for research into 17th-century architecture, garden design, and university life. They provide invaluable visual evidence for understanding the evolution of these historic institutions. The detailed depiction of buildings, some of which no longer exist or have been significantly altered, makes his work an irreplaceable historical archive. His collaborations, such as those with Wenceslaus Hollar on botanical and zoological subjects, also receive attention from historians of science and illustration. The antiquarian and engraver George Vertue (1684–1756), in his invaluable Notebooks, documented information about Loggan, helping to preserve his memory and significance for later art historians.

Conclusion: A Legacy in Line and Detail

David Loggan's career represents a remarkable fusion of artistic talent, technical mastery, and diligent scholarship. From his early training in Danzig and Amsterdam to his celebrated status as the official engraver to the University of Oxford, he consistently demonstrated an unparalleled ability to capture the essence of his subjects, whether the grand architectural ensembles of England's ancient universities or the nuanced likenesses of his portrait sitters.

His magnum opuses, Oxonia Illustrata and Cantabrigia Illustrata, remain his most enduring legacy. These collections of engravings are more than just topographical records; they are profound cultural documents that offer a window into the academic and architectural world of 17th-century England. They celebrate the majesty and intellectual heritage of Oxford and Cambridge, rendered with a precision and artistry that continue to inspire awe. His meticulous bird's-eye views, detailed renderings, and skillful compositions set a new standard for architectural illustration.

Beyond these monumental works, Loggan's contributions to portraiture and book illustration further underscore his versatility and his significant role in the burgeoning print culture of his time. He influenced his contemporaries and successors, and his work continues to be a vital resource for historians and a source of delight for art lovers. David Loggan was, in essence, a visual chronicler of his age, and his engravings provide an invaluable and enduring testament to the architectural and intellectual achievements of Stuart England. His dedication to his craft ensured that the beauty and historical importance of these institutions were preserved for posterity with unparalleled clarity and elegance.