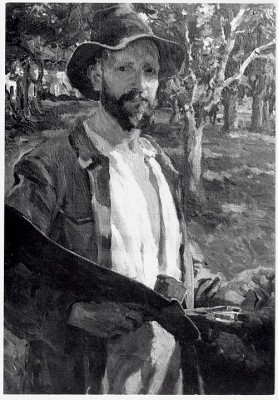

Hans Best, an individual whose life spanned from 1874 to 1942, presents a remarkably complex and multifaceted profile when examining the historical records attributed to his name. Born in Darmstadt, Germany, his journey appears to weave through the realms of art, international politics, intelligence work, and the tumultuous events of the World Wars, culminating in a legacy marked by profound contradictions and significant historical debate. The information available paints a picture of a figure involved in diverse fields, sometimes appearing as an artist rooted in specific traditions, other times as a political actor in high-stakes scenarios, and even as an operative in the clandestine world of espionage. Untangling these threads reveals a narrative filled with dramatic turns and significant, though often conflicting, impacts.

Origins and National Identity

The question of Hans Best's national identity is one of the first complexities encountered. While records firmly place his birth in Darmstadt, Germany, other accounts associate him strongly with Denmark. This Danish connection appears particularly prominent in descriptions of his activities during the Second World War. Evidence suggests he held significant positions related to the German occupation of Denmark, acting as an administrator in Copenhagen and maintaining close ties with the German occupying forces. Some sources explicitly state his nationality as Danish, linking his major life events and political actions directly to Denmark.

However, this contrasts sharply with his German birthplace. This discrepancy raises questions about potential naturalization, dual roles, or perhaps a conflation of identities in historical accounts. Regardless, Darmstadt remains his documented place of birth in 1874. His primary sphere of activity, particularly during the critical period of the Second World War, is consistently described as Denmark, where his actions had significant political repercussions, including involvement in post-war judicial processes concerning the German occupation. His communications between Copenhagen and Berlin further underscore his central role in Danish affairs during this era.

Artistic Style and Representative Works

The artistic identity attributed to Hans Best is described as being aligned with the style of 19th-century French printmakers and illustrators. His early work is characterized as resembling pen drawings or perhaps even whimsical sketches, but he reportedly transitioned towards a more defined technique involving pencil outlines on woodblocks. A key aspect of his artistic practice, as described, was a demand for faithful reproduction in the resulting prints, often accompanied by explanatory text integrated into the underlying layers of the image. This suggests a focus on illustrative clarity and narrative content.

Among the representative works cited are copperplate engravings for the publication Magasin Pittoresque. He is also noted for collaborations on wood engravings with an artist named André. This partnership produced illustrations for a wide range of literary and historical publications. Titles mentioned include The Poet, Poets' Magazine, Don Quixote, The Vicar of Wakefield, Anonymous History, History of Napoleon the Emperor, History of Paris, Frenchmen Painted by Themselves, Travels of Thales, The Wandering Jew, Scenes from Animal Life, and another work titled The Wandering Jew. The specific creation time for the Magasin Pittoresque plates is not given, though his education is placed within the 19th-century French school context. Similarly, the date for the collaboration The Poet with André remains unspecified.

Intriguingly, a specific timeframe of 1989-1991 and 1994 is provided for the work Don Quixote, described as a theatrical music piece inspired by Cervantes' novel, premiering in Stuttgart in 1993 and revised in Heidelberg in 1999. This information seems anachronistic given Best's lifespan (1874-1942) and the 19th-century engraving style otherwise attributed to him, adding another layer of complexity to his artistic profile. The creation date for the History of Paris illustrations is also not specified.

Mentorship and Artistic Influences

Hans Best's artistic formation is linked to the Karlsruhe Art School (Kunstschule Karlsruhe). His primary mentors during his studies there are identified as Ludwig des Coudres and Johann Wilhelm Schirmer. These instructors are said to have profoundly influenced his artistic development. While the exact years Best spent at the Karlsruhe school are not explicitly stated, context can be inferred from the timelines of other artists associated with the institution. For instance, Frederik Thaulow studied there from 1873 to 1875, and Wilhelm Trübner began his studies there in 1867. This suggests Best's period of study likely fell within the mid-to-late 19th century.

The specific nature of the influence exerted by Des Coudres and Schirmer is described as shaping his unique style and technique, encompassing aspects like painting methods, color application, and compositional strategies. Further potential influences are suggested through connections to other artists of the era. The work of Hans von Marées, a German painter active primarily in Italy and influenced by Venetian art, is mentioned in the broader context, as is his association with artists like Adolf Schreyer and Johann Wilhelm Schirmer (again) in Rome. Additionally, the example of Hans Thoma, who also studied at Karlsruhe before moving to Düsseldorf and absorbing influences from modern French art, particularly the works of Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, is raised. While not directly stating these artists influenced Best, their presence in related contexts suggests the rich artistic milieu and cross-currents that might have informed his development.

Involvement in Art Movements and Exhibitions

The figure of Hans Best is associated with significant 20th-century avant-garde art movements, primarily Dadaism and Surrealism. This connection seems largely channeled through the activities of Hans Arp, a key figure in both movements, whose work in Paris and Cologne Dada circles and collaborations with Kurt Schwitters are highlighted. Best's (or perhaps Arp's, attributed to Best) participation in Surrealism is noted through involvement in the first Surrealist exhibition at Galerie Pierre in Paris, alongside prominent artists like Max Ernst and Paul Klee.

Furthermore, participation in various other avant-garde exhibitions is mentioned. This includes shows at the Vienna Künstlerhaus from the mid-1920s to 1939, the "Secession" exhibition of 1926, and a 1927 exhibition at the Bromhead Gallery in London – activities linked in the source material to Hans Figura but presented under the umbrella of Hans Best's context. The narrative also connects Best to international modern art exhibitions, referencing the broad scope of work associated with figures like Hans Richter, encompassing painting, collage, sculpture, works on paper, and prints, often linked to Dada and other avant-garde circles.

An extensive list of prestigious international institutions where "Hans Best's" work or related activities were showcased is provided: the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Madrid), Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (Arizona), ZKM Center for Art and Media (Karlsruhe), MACRO (Rome), Whitechapel Gallery (London), MoMA PS1 (New York), Wallraf-Richartz Museum (presumably Cologne, though listed as Berlin), Hara Museum of Contemporary Art (Tokyo), Shanghai Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art Buenos Aires, Kunsthalle Wien (Vienna), The Drawing Center (New York), Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (Brussels), Frankfurter Kunstverein (Frankfurt), Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (Düsseldorf), and Tate Modern (London). This impressive list suggests a significant international presence within the modern and contemporary art world.

Adding another dimension, Best is credited with curatorial activities focusing on Chinese avant-garde art. Specifically, exhibitions held in Berlin in 1991 and 1993, organized by "Dai Hanzhi (Hans)," are mentioned. These exhibitions, including a major show at Berlin's Haus der Kulturen der Welt in 1993, were pivotal in introducing modern Chinese art to a wider European audience, attracting collectors and galleries and significantly impacting the trajectory of contemporary Chinese art on the global stage. This curatorial role, attributed within the context of Hans Best, further diversifies his purported activities.

Espionage and Wartime Experiences

Beyond the art world, a dramatic narrative of espionage and wartime experiences is attributed to Hans Best. During the First World War, he is described as a highly successful British intelligence officer operating out of the Netherlands. His key achievement during this period was reportedly establishing an effective intelligence network within German-occupied Belgium. This portrayal casts him as a skilled operative working against Germany during the Great War.

Following the end of WWI, this narrative continues with Best returning to the Netherlands, settling in The Hague, marrying, and venturing into the world of business. However, his respite from intelligence work was apparently temporary. As the clouds of the Second World War gathered, he was reportedly recruited back into intelligence service. His activities during WWII culminated in his capture by the Germans.

The account details his harrowing experience as a prisoner of war. In May 1945 (a date potentially problematic as it's after VE Day, unless referring to capture before then and imprisonment continuing), he, along with an associate named Stevens, was allegedly taken at gunpoint across the border into Germany. His journey through captivity included being sent to Düsseldorf, then transported by train to the Gestapo headquarters in Berlin around September 11, 1945. From there, on September 12, 1945, he and fellow prisoners were transferred to the notorious Sachsenhausen concentration camp. After the war's conclusion and his eventual release, he is said to have returned to Britain and penned a best-selling book detailing his wartime ordeals. The title mentioned in the source text is Measuring the World, noted as Europe's top bestseller in 2006 about scientists Humboldt and Gauss – another striking anachronism and likely misattribution, as the famous account of the Venlo incident and subsequent captivity was written by Sigismund Payne Best himself.

Role in Occupied Denmark and Political Actions

Contrasting sharply with the narrative of a British spy is the detailed account of Hans Best's role as a high-ranking German official in occupied Denmark during World War II. He is identified as the Reich Plenipotentiary (Reichsbevollmächtigter), effectively the top civilian administrator representing German interests, overseeing the Danish government and judicial system under occupation. This position placed him at the center of Danish political life during a critical and fraught period.

Initially, Best is described as pursuing a relatively moderate policy, aiming to maintain stability through cooperation with the existing Danish administration and business community. Evidence of this includes his allowance of parliamentary and local elections in 1943, seemingly an attempt to preserve a facade of Danish autonomy. However, the escalating pressures of war and Nazi ideology complicated this approach, particularly concerning the persecution of Jews.

In September 1943, Best reportedly proposed a "solution" for Denmark's Jewish population, suggesting the dissolution of Jewish organizations and redistribution of property, alongside forming a new government based on the Danish constitution. This proposal, however, was not implemented. As the situation deteriorated and demands from Berlin, particularly from SS leader Heinrich Himmler, intensified, Best's stance shifted. Following a German ultimatum to the Danish government on August 28, 1943, demanding martial law, curfews, and the death penalty for sabotage, Best's position hardened. A telegram dated September 8, 1943, shows him recommending the arrest of Danish Jews and prominent liberals, possibly to demonstrate loyalty to Hitler after the Danish government resigned rather than accept the ultimatum.

Despite this, other accounts suggest Best simultaneously attempted to manage the situation in a way that preserved his working relationship with Danish civil servants. There are claims he deliberately leaked information about the impending roundup of Jews planned for early October 1943. This warning is credited with enabling the vast majority of Denmark's Jewish population (over 7,000 people) to escape across the Øresund to neutral Sweden. While nearly 500 were captured and deported to Theresienstadt, the escape of so many is often cited as a unique event in the history of the Holocaust. Best's role remains debated: was the leak intentional humanitarianism, a calculated political move, or simply an unintended consequence of internal communications?

His administration also took harsh measures against the growing Danish resistance movement. He publicly condemned resistance activities and called for German reprisals, reportedly advising Himmler to adopt even stricter measures to suppress dissent. Ultimately, the combination of increasing resistance, the failure of the cooperative policy, and the changing military situation led to his recall by Hitler around August 29, 1943 (coinciding with the imposition of direct military rule), being replaced by Werner von Hanneken.

Post-War Judgment and Historical Legacy

The conclusion of World War II brought a reckoning for Hans Best's actions as the German Plenipotentiary in Denmark. He faced trial and was convicted by Danish courts. The charges against him were serious, reflecting his high-level responsibility within the occupation regime. Key accusations included his role in the persecution of Danish Jews, specifically the October 1943 roundup that led to deportations and deaths in Theresienstadt, even if many escaped.

He was also held responsible for German terror actions, including the arrest and potential killing of Danish police officers in September 1944 (though the source text mentions 1943 arrests leading to his own transfer to Germany in December 1943, adding confusion). His earlier role, from 1940 to 1942, as chief of the military administration in occupied France, overseeing the suppression of the French Resistance and implementing anti-Jewish policies ("de-Judaization"), was also cited as part of his culpability.

His historical assessment remains deeply contested. On one hand, he was a high-ranking Nazi official, an SS member (though the rank varies in sources, often cited as SS-Obergruppenführer for Werner Best), deeply involved in the administration of an oppressive occupation and implicated in war crimes. His ideological leanings are described as aligning with the "heroic realism" of thinkers like Ernst Jünger, characterized by a critique of Western liberalism and individualism, fitting within the broader intellectual currents that fed Nazism.

On the other hand, the narrative of the leaked warning saving Danish Jews complicates his legacy, leading some to portray him as a more pragmatic or even conflicted figure than other Nazi leaders. However, this interpretation is heavily debated by historians, many of whom emphasize his fundamental commitment to the Nazi regime and his ultimate responsibility for implementing its policies, regardless of any tactical maneuvering. His conviction underscores the post-war legal judgment that his actions constituted serious crimes. The social evaluation thus oscillates between condemnation as a perpetrator within the Nazi system and a more nuanced, though controversial, view acknowledging the complexities of his actions in Denmark.

Collaborations and Final Assessment

Throughout the varied accounts, collaboration is a recurring theme, though with different partners depending on the context being described. In the artistic realm, the partnership with the engraver André is noted for producing illustrations for numerous 19th-century publications. In the political sphere of occupied Denmark, his interactions, whether cooperative or coercive, with Danish officials, German military commanders, and superiors in Berlin like Himmler and Hitler, defined his tenure. Even in the espionage narrative, collaboration (with fellow agent Stevens) and opposition (against German authorities) are central.

In conclusion, the figure identified as Hans Best (1874-1942) emerges from the available information not as a single, coherent individual, but as a composite, potentially reflecting the conflation of several historical persons. The narrative encompasses the life of a German painter born in Darmstadt, the career of a 19th-century French engraver, the experiences of a British intelligence agent, the activities of avant-garde artists like Hans Arp and Hans Richter, the curatorial work of Hans van Dijk, and, most prominently, the actions and controversial legacy of the high-ranking Nazi official Werner Best in occupied Denmark. While Hans Best the painter did exist (1874-1942, known for genre scenes and portraits, associated with Munich), the information presented weaves a far more complex, contradictory, and ultimately historically fragmented tapestry under his name. Disentangling these threads is crucial for accurate historical understanding, but the combined narrative, as presented, offers a bewildering glimpse into the intersections of art, war, politics, and identity across a turbulent period of European history.