David Martin stands as a significant figure in the landscape of eighteenth-century British art. A skilled Scottish painter and engraver, he navigated the bustling art scenes of both London and Edinburgh, leaving behind a valuable visual record of his time, particularly capturing the likenesses of key figures during the remarkable period known as the Scottish Enlightenment. His career bridges the gap between his celebrated teacher and the next generation of Scottish portraitists, securing his place in the annals of art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the coastal town of Anstruther, Fife, in 1737, David Martin's artistic journey began under promising tutelage. His innate talent likely became apparent early on, leading him to the studio of one of Scotland's most successful artists, Allan Ramsay (1713-1784). Moving to London, Martin entered Ramsay's workshop, not merely as a student but eventually as a trusted assistant. This period was crucial for his development, immersing him in the techniques and stylistic sensibilities of his master.

Ramsay's influence on Martin was profound and enduring. Known for his elegant, sensitive portraits, Ramsay instilled in his pupil a refined approach to capturing likeness and character. It is highly probable that Martin accompanied Ramsay on his second visit to Italy in the late 1750s. Such a journey would have exposed Martin firsthand to the masterpieces of the Renaissance and the burgeoning Neoclassical movement, broadening his artistic horizons and exposing him to the works of continental masters like Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787) and Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-1779), whose studios were essential stops for artists on the Grand Tour.

Working within Ramsay's studio, Martin would have honed his skills by assisting with drapery, backgrounds, and potentially creating replicas of Ramsay's popular compositions. This practical experience was invaluable, providing him with the technical proficiency and understanding of the portraiture business necessary to launch his own independent career. The polish and grace evident in Ramsay's work became hallmarks that Martin would adapt into his own distinct style.

Launching a Career in London

By the early 1760s, David Martin felt ready to establish himself as an independent artist. He set up his own studio in London, the vibrant epicentre of the British art world. This was a bold move, placing him in direct competition with the titans of English portraiture, Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) and Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), as well as other popular artists like George Romney (1734-1802) and Francis Cotes (1726-1770).

To gain recognition, Martin actively participated in London's exhibition culture. He submitted works to the Incorporated Society of Artists, a key venue for artists seeking patronage and public acclaim before the Royal Academy fully established its dominance. His exhibits showcased his developing talent and ambition. It was during this London period that he painted one of his most famous and enduring portraits.

In 1767, Martin created a striking portrait of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), the American polymath, writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, and diplomat, who was then residing in London as an agent for several colonies. Known as the 'thumb portrait', it depicts Franklin seated, his chin resting thoughtfully on his thumb. The work is celebrated for its directness, capturing the intellectual weight and composed demeanour of its subject. This portrait, widely reproduced through Martin's own mezzotint engraving, significantly boosted his reputation on both sides of the Atlantic.

Despite successes like the Franklin portrait, the London market was fiercely competitive. While Martin achieved a degree of recognition, establishing a truly dominant practice amidst such formidable rivals proved challenging. His Scottish roots and connections, however, would soon draw him back north.

Return to Scotland: Edinburgh's Leading Painter

Around the mid-1770s, David Martin made the pivotal decision to relocate his primary practice from London to Edinburgh. This move proved highly advantageous. While London boasted numerous star painters, Edinburgh's art scene, though vibrant, had fewer established portraitists of Martin's calibre following Ramsay's increasing focus on his role as Painter in Ordinary to King George III and his subsequent retirement.

Martin quickly established himself as the leading portrait painter in the Scottish capital. His London experience, combined with his refined technique and ability to capture a strong likeness, made him highly sought after by Scotland's nobility, gentry, and the intellectual luminaries of the Enlightenment. He opened a studio that became a focal point for commissioning portraits.

His prominence was officially recognized when he was appointed Principal Painter to His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales (the future King George IV) for Scotland. This prestigious appointment cemented his status as the pre-eminent portraitist in the country, further enhancing his appeal to patrons seeking fashionable and high-quality likenesses. He effectively filled the void left by Ramsay's reduced activity in Scotland.

For nearly two decades, Martin dominated the portrait market in Edinburgh. His studio was prolific, producing numerous portraits that captured the faces of a generation shaping Scotland's cultural, intellectual, and social landscape. He became the go-to artist for those wishing to have their status and character immortalized on canvas.

Artistic Style and Technical Skill

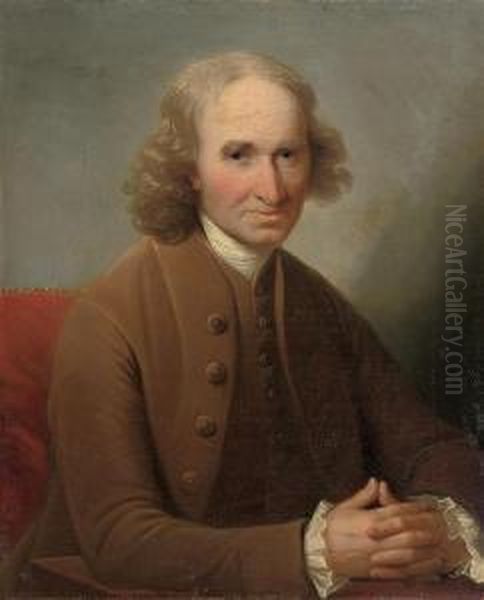

David Martin's style is characterized by its clarity, competence, and sensitivity, clearly reflecting the influence of Allan Ramsay but developing into a distinct artistic voice. He generally favoured accurate representation over excessive flattery, though he could certainly employ the conventions of the "Grand Manner" when depicting high-status individuals, using pose, setting, and attire to convey dignity and importance.

His draughtsmanship was solid, and he possessed a keen eye for capturing individual likenesses. His portraits often convey a sense of the sitter's personality, whether it be the intellectual intensity of a philosopher or the assured poise of an aristocrat. He paid meticulous attention to the rendering of fabrics and details – lace, silks, velvets, and powdered wigs are often depicted with considerable skill, adding richness and texture to his compositions.

Compared to the painterly bravura of Gainsborough or the complex allegorical references sometimes found in Reynolds' work, Martin's approach was generally more direct and restrained, aligning with the Neoclassical taste for clarity and order that was gaining ascendancy during his career. His colour palettes are often harmonious and controlled, contributing to the overall sense of composure in his portraits.

Beyond painting, Martin was an accomplished engraver, particularly skilled in the technique of mezzotint. Mezzotint allowed for rich tonal gradations, making it ideal for reproducing the nuances of oil paintings. He frequently created engravings after his own portraits, such as the Benjamin Franklin likeness, which helped disseminate his work to a wider audience. He also engraved works by other artists, including his master, Allan Ramsay, further demonstrating his versatility and technical prowess in printmaking.

Documenting the Scottish Enlightenment

One of David Martin's most significant contributions is his role as a visual chronicler of the Scottish Enlightenment. This extraordinary period, roughly spanning the mid-eighteenth to the early nineteenth century, saw Scotland achieve international renown for its intellectual and scientific accomplishments. Figures based in Edinburgh and other Scottish cities made groundbreaking contributions to philosophy, economics, literature, medicine, science, and architecture.

Martin painted portraits of several key figures associated with this movement. His likeness of the philosopher David Hume (1711-1776), painted around 1770, captures the penetrating gaze and thoughtful mien of one of the era's most influential thinkers. Similarly, his portrait of Dr. Joseph Black (1728-1799), the pioneering chemist known for his discoveries regarding carbon dioxide and latent heat, presents a figure of quiet scientific authority.

These portraits, along with others of lawyers, physicians, academics, and landowners, provide invaluable visual documentation of the individuals who shaped this remarkable intellectual flourishing. Martin's work allows us to connect faces with the names and ideas that defined the Scottish Enlightenment, offering insight into how these prominent individuals wished to be perceived by their contemporaries and posterity. His realistic yet dignified style was well-suited to capturing the serious intellectual and social purpose of these sitters.

Other notable sitters included William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield (1705-1793), the influential Lord Chief Justice (though born in Scone, Perthshire, his career was primarily in London, Martin painted a well-known portrait of him). He also painted numerous members of the Scottish aristocracy and landed gentry, whose patronage was essential for any successful portraitist of the time.

There is also the intriguing case of the double portrait depicting Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray, long attributed to the German painter Johann Zoffany (1733-1810). However, recent scholarship has questioned this attribution, and David Martin, given his connections to the sitters' family (the Earl of Mansfield was Dido's great-uncle and guardian) and stylistic similarities, has been suggested as a possible author, or perhaps an artist within Ramsay's circle. While attribution remains debated, the painting itself is a remarkable work of the period.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

David Martin occupied an important position within the broader context of British art. His training directly linked him to Allan Ramsay, a foundational figure in British portraiture. While working in London, he operated alongside the dominant figures of Reynolds and Gainsborough, absorbing the competitive atmosphere and high standards of the capital. His contemporaries also included notable female artists like Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807), a Swiss-born Neoclassical painter and founding member of the Royal Academy, and history painters such as the American-born Benjamin West (1738-1820), who succeeded Reynolds as President of the Royal Academy.

In Scotland, Martin's return coincided with a period where he faced relatively little direct competition at the highest level. However, the artistic landscape was not static. Younger Scottish artists were emerging, including Alexander Nasmyth (1758-1840), known for both portraits and landscapes, and Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798), a fellow Scot who became a key figure in Neoclassical history painting, primarily based in Rome but influential through his works and engravings.

Crucially, towards the end of Martin's career, another major talent rose to prominence in Edinburgh: Sir Henry Raeburn (1756-1823). Raeburn developed a bolder, more direct, and often more psychologically penetrating style of portraiture. By the 1790s, Raeburn began to eclipse Martin as the most fashionable portrait painter in Scotland. Raeburn's vigorous brushwork and dramatic use of light offered a distinct alternative to Martin's more meticulous and polished approach. Martin's death in 1798 occurred just as Raeburn was solidifying his own dominance, which would last for decades.

Martin's career thus represents a vital link. He inherited the mantle from Ramsay in Scotland and upheld a high standard of portraiture, influenced by the prevailing Neoclassical tastes, before the emergence of the distinctively robust style of Raeburn. He navigated the transition between these major figures in Scottish art.

Later Years and Legacy

David Martin continued to work actively in Edinburgh throughout the 1780s and into the 1790s, although his position was increasingly challenged by the rising star of Henry Raeburn. He maintained his studio and continued to receive commissions, benefiting from his established reputation and official appointment.

He passed away in Edinburgh on 30 December 1798, leaving behind a substantial body of work. His legacy rests on several key contributions. Firstly, he was the leading Scottish portrait painter of his generation, effectively bridging the era of Ramsay and the era of Raeburn. Secondly, his portraits provide an invaluable visual record of the Scottish Enlightenment, capturing the likenesses of many of its most important figures. Thirdly, his skill as a mezzotint engraver allowed for the wider dissemination of his images and those of others, contributing to the visual culture of the time.

His works are held in numerous public collections, including the National Galleries of Scotland, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow, and various museums and institutions in the UK and abroad, including collections in the United States owing to the fame of his Franklin portrait.

While perhaps overshadowed in popular memory by Ramsay before him and Raeburn after him, David Martin's consistent quality, his significant output, and his role in documenting a pivotal era in Scottish history ensure his enduring importance. He was a highly competent and sensitive artist who captured the faces of his time with skill and dignity.

Conclusion

David Martin's career exemplifies the life of a successful professional artist in eighteenth-century Britain. Trained by a master, he navigated the competitive London art world before establishing a dominant practice in his native Scotland. His portraits, characterized by their clarity, detail, and insightful likenesses, offer a window into the society of his time, particularly the intellectual ferment of the Scottish Enlightenment. As both a painter and an engraver, he made significant contributions to the artistic landscape, securing his place as a key figure in the history of Scottish art, adeptly capturing the spirit and the personalities of a remarkable age. His work remains a testament to his skill and a valuable resource for understanding the visual culture of the late eighteenth century.