Lemuel Francis Abbott stands as a significant figure in the landscape of late 18th-century British portraiture. Active during a period of immense social, political, and naval change, Abbott captured the likenesses of some of the era's most prominent figures, leaving behind a body of work valued for its directness and historical importance. Though perhaps overshadowed in artistic innovation by giants like Sir Joshua Reynolds or Thomas Gainsborough, Abbott carved a distinct niche, particularly renowned for his depictions of naval heroes and men of intellect. His life, marked by both considerable artistic success and profound personal challenges, offers a compelling glimpse into the world of a working artist navigating the demands of patronage and the complexities of life in Georgian London. Born around 1760 or 1761 and passing away in 1802, his relatively short career nonetheless produced images that continue to define our visual understanding of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Lemuel Francis Abbott entered the world in the parish of Ansty, Leicestershire, likely in 1760 or 1761. He was the son of the Reverend Lemuel Abbott, who served as a clergyman in Ansty and later Thornton, and his wife, Mary. Growing up in a clerical household provided a certain background, but young Lemuel's inclinations steered him towards the visual arts rather than the church. His formal artistic training began relatively early, around the age of fourteen.

In 1775, Abbott was sent to London to become a pupil of Francis Hayman. Hayman was a notable figure in the London art scene, a charter member of the Royal Academy, and known for his history paintings, decorative works (famously for Vauxhall Gardens), and portraits. He was part of an older generation, linked to William Hogarth and the St Martin's Lane Academy, representing a style often infused with Rococo liveliness. However, Abbott's time under Hayman's direct tutelage was cut short by the master's death in 1776.

Following Hayman's demise, Abbott did not immediately seek out another master. Instead, he returned to his parents' home in Leicestershire. This period proved crucial for his development. Away from the direct influence of a London studio, Abbott appears to have dedicated himself to self-study, honing his skills independently. This reliance on personal practice and observation likely contributed to the development of his distinct, often straightforward style, perhaps less influenced by the prevailing academic trends than some of his contemporaries who spent longer periods in formal training or travelling abroad. His early development was thus a blend of brief formal instruction and sustained independent effort.

Establishing a London Career

Around 1780, feeling sufficiently skilled and ready to establish himself professionally, Lemuel Francis Abbott made the decisive move back to London. This relocation marked the true beginning of his independent career as a portrait painter. Shortly after settling in the capital, he married Anna Maria, and the couple established a home, providing a base from which he could pursue commissions and engage with the city's vibrant, competitive art market.

London was the undeniable centre of the British art world. Abbott began submitting his work to the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy of Arts at Somerset House. These exhibitions were the premier showcase for artists, offering vital opportunities for visibility, critical notice, and attracting patronage. Abbott became a regular exhibitor, presenting his portraits to the public and his peers. His participation indicates his ambition and his engagement with the established art institutions of the day.

However, despite his regular presence at the Academy exhibitions, Abbott never achieved the distinction of being elected an Associate (ARA) or a full Royal Academician (RA). This is noteworthy, especially considering the quality and popularity of some of his work. Membership in the Academy, presided over by figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds, conferred significant prestige and professional advantage. Artists like Thomas Gainsborough (though often at odds with the RA), George Romney, John Hoppner, and the rising star Thomas Lawrence were among the prominent portraitists who held or would achieve Academician status during or shortly after Abbott's active years. Abbott's lack of formal RA recognition suggests he operated somewhat outside the inner circle, perhaps due to his less academic training, his specific focus, or maybe even aspects of his temperament or professional connections.

Portraitist of Naval Heroes: The Nelson Connection

While Abbott painted various members of society, his most enduring fame rests on his portraits of naval officers, particularly those of Horatio Nelson, Britain's greatest naval hero. During the turbulent decades of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the Royal Navy was Britain's shield and sword, and its commanders were celebrated public figures. Abbott became one of the go-to artists for capturing their likenesses.

His association with Nelson is paramount. Abbott painted Nelson on several occasions, most notably around 1797-1798, following Nelson's victory at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent and the loss of his right arm at Santa Cruz de Tenerife. The resulting portraits are arguably the most famous and widely reproduced images of the admiral. One iconic version, showing Nelson in his Rear-Admiral's undress uniform, his empty right sleeve pinned across his chest, is housed in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Another significant version resides in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

These Nelson portraits are characteristic of Abbott's strengths: a direct, unidealized likeness that conveys determination and character. Unlike the grander, more allegorical portraits favoured by some contemporaries like Reynolds, Abbott focused on the man himself. The paintings capture Nelson's relatively slight frame, his intense gaze, and the visible cost of his service. This authenticity resonated powerfully in an era of patriotic fervor. Abbott's ability to secure sittings with Nelson, likely facilitated through naval connections or mutual acquaintances, cemented his reputation in this specific, highly visible field. He also painted other notable naval figures, contributing significantly to the visual record of Britain's maritime power during this critical period.

Capturing Men of Letters and Science

Beyond the quarterdeck, Abbott also turned his brush to figures from the worlds of literature, science, and the arts. This demonstrates a broader engagement with the intellectual currents of his time. While perhaps less numerous than his naval portraits, these works showcase his versatility in capturing different facets of personality and profession.

A notable example is his portrait of the poet William Cowper. Cowper was a highly regarded, though often reclusive, literary figure of the late 18th century. Abbott's portraits of him, like his naval commissions, are known for their sensitivity and directness, attempting to convey the sitter's inner life. These images became important representations of the poet.

Equally significant is Abbott's portrait of the astronomer Sir William Herschel, painted in 1785 and now held by the National Portrait Gallery. Herschel, famous for discovering the planet Uranus and for his pioneering work in deep-sky astronomy, is depicted with an air of thoughtful inquiry. Painting such a prominent scientific figure indicates Abbott's access to diverse circles of patronage and his ability to render intellectuals convincingly. This contrasts with artists like Joseph Wright of Derby, who often placed his scientific subjects within dramatic, atmospherically lit scenes related to their experiments. Abbott’s approach remained focused on the portrait likeness.

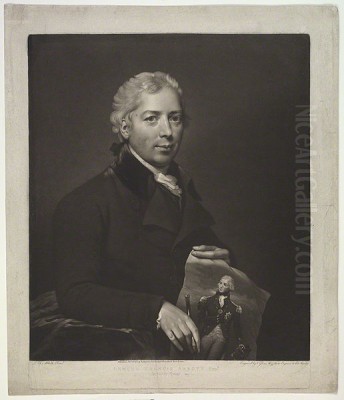

He also painted fellow artists, such as the renowned Italian engraver Francesco Bartolozzi, who was highly active and influential in London. Abbott's 1792 portrait of Bartolozzi is now in the Tate Britain collection. Bartolozzi himself was an RA, highlighting the interconnectedness of the London art world, even for an artist like Abbott who remained outside the Academy's formal membership. These portraits of non-military figures underscore Abbott's role as a broader chronicler of the faces shaping Georgian Britain's cultural and intellectual landscape, alongside contemporaries like Allan Ramsay or the aforementioned George Romney.

Artistic Style and Technique

Lemuel Francis Abbott developed a distinctive style of portraiture that, while operating within the broad conventions of the late Georgian period, possessed its own specific characteristics. Some sources loosely associate his work with the Rococo, possibly reflecting the influence of his brief training under Francis Hayman. However, his mature style aligns more closely with the burgeoning Neoclassicism and a straightforward, empirical approach to likeness that gained favour towards the end of the 18th century.

Abbott's primary strength lay in capturing a convincing likeness. His portraits are often described as direct, honest, and sometimes unflattering, particularly evident in the famous depictions of Nelson, which do not shy away from the admiral's physical frailties. He seemed less concerned with idealization or demonstrating painterly flourish for its own sake, unlike Reynolds with his complex poses and rich textures, or Gainsborough with his feathery brushwork and landscape backgrounds. Abbott's focus remained firmly on the sitter's face and character.

His compositions were often relatively simple, frequently concentrating on the head and shoulders or a three-quarter length format. The input text noted a characteristic use of tilted bodies or turned heads, introducing a subtle dynamism and preventing the portraits from appearing too static. This compositional device helps to engage the viewer and adds a sense of immediacy. His handling of paint was generally competent and solid, rendering features and fabrics with clarity but without the bravura technique seen in some of his more celebrated rivals like Sir Thomas Lawrence, whose dazzling style was beginning to emerge towards the end of Abbott's life.

While perhaps lacking the innovative flair or psychological depth found in the very greatest portraitists of the era, Abbott's technique was well-suited to his clientele, particularly the naval officers who likely valued accuracy and a sense of resolute character over artistic artifice. His consistent quality and reliable likenesses ensured a steady stream of commissions throughout the 1780s and 1790s.

Personal Struggles and Untimely End

Despite his professional success and the high profile of many of his sitters, Lemuel Francis Abbott's personal life took a tragic turn towards the end of the century. Sources indicate that around 1798, or possibly slightly later in 1800, Abbott began to suffer from serious mental health problems. He was eventually declared insane.

The precise nature of his illness is not documented in detail, but contemporary accounts, as referenced in the initial input, suggested it stemmed from domestic troubles, specifically an "unmatched marriage" or difficulties in his relationship with his wife, Anna Maria. The pressures of maintaining a career as an artist in a competitive environment, potential financial worries, or underlying predispositions could also have played a role, but the marital difficulties are the most frequently cited factor in historical accounts.

This devastating development effectively ended his painting career. An artist reliant on keen observation, steady hands, and social interaction for sittings could not continue to work under such circumstances. His condition necessitated care, marking a sad conclusion to a productive artistic life. Lemuel Francis Abbott died on December 5, 1802, in London. He was only in his early forties (around 42 or 43 years old), his potential likely not yet fully realized. His death removed a skilled practitioner from the London art scene, a contemporary of figures like John Opie and Henry Raeburn who continued to shape British portraiture into the early 19th century.

Legacy and Reputation

Lemuel Francis Abbott's legacy is intrinsically linked to his portraits of Horatio Nelson. These images became iconic almost immediately and have remained the definitive likenesses of the admiral, reproduced countless times in prints, books, and biographies. Their presence in major public collections like the National Portrait Gallery and the National Maritime Museum ensures their continued visibility and Abbott's association with one of Britain's most revered historical figures.

Beyond the Nelson connection, Abbott is recognized for his valuable contributions to the iconography of the late Georgian era. His portraits of other naval commanders, politicians, scientists like Herschel, and literary figures like Cowper provide important visual records. Works like the portrait of the engraver Francesco Bartolozzi at Tate Britain further attest to his place within the artistic community of his time.

However, his critical reputation has sometimes been overshadowed by the towering figures of Reynolds, Gainsborough, Romney, and Lawrence. His lack of RA membership and the tragic curtailment of his career by mental illness may have contributed to him receiving less scholarly attention compared to his Academician contemporaries. Some assessments might view him as a competent but perhaps secondary figure, a reliable face-painter rather than a major innovator.

Yet, this perspective perhaps undervalues his specific achievements. Abbott excelled at capturing a direct, unvarnished likeness, a quality highly valued by many patrons and crucial for historical portraiture. His work provides a fascinating counterpoint to the grander styles of his rivals. While not a stylistic trailblazer, he fulfilled an important role, documenting the key players of a dramatic period in British history with clarity and skill. His enduring connection to Nelson guarantees him a permanent, if specific, place in the annals of British art.

Conclusion

Lemuel Francis Abbott navigated the London art world of the late 18th century with considerable skill, establishing himself as a sought-after portraitist, particularly for the nation's naval heroes. His iconic images of Horatio Nelson have secured his lasting fame, defining how generations have visualized the celebrated admiral. While his artistic approach favoured direct representation over the flamboyant styles of some contemporaries, his ability to capture a strong likeness and convey character earned him numerous important commissions, from military leaders to men of science and letters. His career, tragically cut short by mental illness, underscores the personal challenges that could accompany artistic life. Though perhaps not ranked among the absolute giants of British art like Reynolds or Gainsborough, Abbott remains a significant figure, a dedicated chronicler whose brush captured the faces of a pivotal era with honesty and enduring historical value. His work continues to offer invaluable insights into the personalities and appearances of those who shaped late Georgian Britain.