David Ossipovitch Widhopff (1867-1933) stands as a fascinating, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of Parisian art at the turn of the 20th century. Born in the village of Shorchekasy, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, Widhopff's artistic journey would lead him to the heart of European modernism, Paris. Here, he carved out a distinctive niche as a painter, a gifted caricaturist, an innovative poster artist, and a keen observer of urban life, leaving behind a body of work that reflects the dynamism and multifaceted nature of the Belle Époque.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Russia and Paris

David Ossipovitch Widhopff, whose original name was David Osipovich Vidgof, was born on May 5, 1867, in Odessa, a cosmopolitan port city on the Black Sea, known for its burgeoning cultural scene. Some sources also mention Shorchekasy as his birthplace, indicating the complexities often found in tracing the early lives of artists from this era and region. His initial artistic training took place in his homeland, where he attended the Imperial Academy of Arts in Moscow. This institution, while traditional, would have provided him with a solid grounding in academic drawing and painting techniques, a foundation that would serve him well throughout his diverse career.

Seeking broader artistic horizons and drawn by Paris's reputation as the undisputed capital of the art world, Widhopff relocated to the French metropolis in 1887, at the age of twenty. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, both French and international, he enrolled at the Académie Julian. This private art school was a popular alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts, offering a more liberal environment and attracting a diverse student body. At the Académie Julian, Widhopff studied under the tutelage of respected academic painters such as Tony Robert-Fleury and Jules Joseph Lefebvre. Both were influential figures in the Salon system, known for their historical and allegorical paintings, as well as their portraiture. This training further honed his technical skills, particularly in figure drawing and composition.

Emergence in the Parisian Art World: Salons and Early Recognition

Widhopff quickly began to make his mark on the Parisian art scene. He started exhibiting his paintings at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Participation in the Salon was a crucial step for any artist seeking recognition and patronage. Widhopff's works were accepted and shown in the Salons of 1888, 1891, and 1893. These early Salon appearances would have featured his paintings, likely demonstrating the academic proficiency he had acquired, possibly in genres such as portraiture, genre scenes, or still lifes.

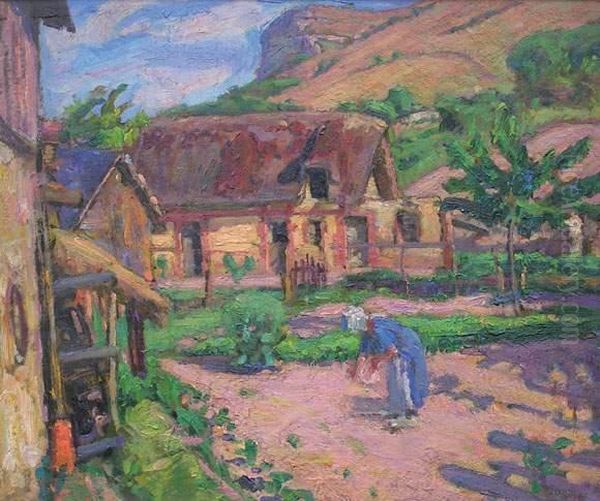

His paintings from this period and later often explored traditional subjects but with a keen eye for contemporary life and a robust, expressive touch. He was known for his still life compositions, such as the evocatively titled "Still-life" and "Nature morte aux raisins" (Still Life with Grapes), which showcased his ability to render textures and light with sensitivity. His landscapes, like "Ferme" (Farm), captured the rustic charm of the French countryside, while his portraits aimed to convey the character of his sitters. The art market recognized his talent, with works like "Le portrait de l'amie Berthe" (Portrait of the friend Berthe), an oil painting, achieving notable prices at auction in later years.

The Illustrator and Caricaturist: Chronicler of Parisian Life

While Widhopff pursued traditional painting, a significant and perhaps more widely recognized aspect of his oeuvre was his work as an illustrator and caricaturist. He became a prominent contributor to some of Paris's leading illustrated journals, most notably Le Courrier Français. This weekly satirical magazine, founded by Jules Roques in 1884, was renowned for its witty social commentary, its often risqué humor, and its high-quality illustrations by a roster of talented artists. Widhopff's contributions were numerous, and he became one of its mainstays.

His illustrations for Le Courrier Français captured the vibrant, often frenetic, life of Paris. He depicted actors, singers, writers, fellow artists, and the denizens of Montmartre's cabarets and cafes. His style in these works was dynamic and expressive, often with a humorous or satirical edge. He had a knack for capturing a likeness and a personality with a few deft strokes. This work placed him in the company of other notable illustrators for the journal, such as Adolphe Willette, Jean-Louis Forain, and at times, Théophile Steinlen, all of whom were chronicling the social fabric of the city. The influence of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, another master observer of Parisian nightlife and a brilliant graphic artist, is often noted in Widhopff's illustrative style, particularly in the fluid lines and the focus on capturing movement and character.

Widhopff also contributed to other publications, including La Plume, an influential literary and artistic review that played a significant role in promoting Art Nouveau and Symbolism. It was for La Plume in 1897 that Widhopff created a notable portrait of the Czech artist Alphonse Mucha, a key figure in the Art Nouveau movement. This portrait helped to introduce Mucha to a wider Parisian audience. He also collaborated with artists like Jacques Villon on the journal Cocorico, further cementing his presence in the world of graphic arts and illustration. His work extended to newspaper illustrations, demonstrating his versatility and the demand for his keen observational skills.

Poster Art and Graphic Design: The Visual Language of the Belle Époque

The Belle Époque was the golden age of the poster, and Widhopff also made contributions to this burgeoning art form. While perhaps not as singularly focused on posters as specialists like Jules Chéret, the "father of the modern poster," or Alphonse Mucha himself, Widhopff's skills in composition, color, and capturing attention were well-suited to poster design. His aforementioned portrait of Mucha for La Plume had the impact of a promotional image, highlighting the artist's persona.

His graphic work, in general, shared the era's enthusiasm for bold design and the integration of image and text. The ability to create striking visuals that could communicate quickly and effectively was paramount, whether for a magazine cover, an advertisement, or a theatrical announcement. Widhopff's experience as an illustrator, with its emphasis on narrative and character, naturally fed into his approach to graphic design. His style, influenced by the sinuous lines of Art Nouveau and the directness of contemporary caricature, allowed him to create memorable images.

Artistic Style: Power, Passion, and Versatility

David Widhopff's artistic style was characterized by its energy, versatility, and a certain robust quality. In his paintings, whether still lifes, landscapes, or portraits, there is often a tangible sense of form and a confident handling of paint. His color palettes could range from subtle and harmonious to bold and expressive, depending on the subject and mood. His academic training provided him with a strong command of anatomy and perspective, which he then adapted to his own expressive ends.

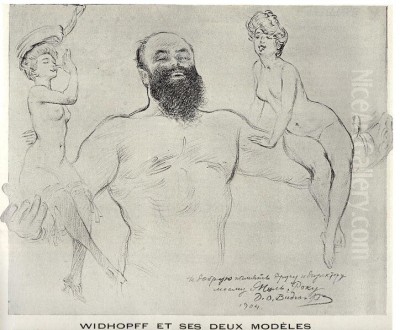

In his graphic work, his line was particularly distinctive – fluid, dynamic, and capable of conveying both elegance and caricature. He could capture the essence of a personality or a scene with remarkable economy. The critic Marcel Lamare, writing about Widhopff, praised his "Herculean strength and passion," and noted that his work was filled with "health, strength, and feminine charm." This suggests an art that was perceived as vigorous and vital, yet also capable of sensitivity and allure.

His ability to move between different media – oil painting, watercolor, lithography, pen-and-ink drawing – and different genres – from formal portraiture to satirical cartoons – speaks to his remarkable adaptability. He was not an artist confined to a single mode of expression but rather one who embraced the diverse opportunities available in the rich artistic environment of Paris. This versatility was a hallmark of many artists of the period, who often did not see a rigid distinction between "high" art (painting) and "applied" art (illustration, posters).

Connections and Collaborations: A Figure in the Artistic Milieu

Widhopff was an active participant in the Parisian art world, and his career was marked by numerous connections and collaborations. His friendship with Alphonse Mucha is well-documented, highlighted by the La Plume portrait. This connection places Widhopff within the orbit of Art Nouveau, even if his own style was more eclectic.

His collaboration with Jacques Villon on Cocorico links him to another significant artist who, like his brothers Marcel Duchamp and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, would go on to play a crucial role in the development of modern art. Widhopff's association with Henri Gabriel Ibels, another artist known for his posters and illustrations, particularly of café-concert life, is also noted, with connections traced through shared subjects, such as a portrait sketch of the singer Marguerite Dufay.

He also maintained friendships and professional relationships with fellow Russian émigré artists in Paris, such as Alexandre Altmann, with whom he held joint exhibitions. The presence of a significant Russian artistic community in Paris, including figures like Léon Bakst (famous for his work with Diaghilev's Ballets Russes) and later Marc Chagall and Chaïm Soutine, created a supportive network and a rich cultural exchange. Widhopff would have been part of this vibrant expatriate scene.

The artists he worked alongside at Le Courrier Français and other journals, such as Willette, Forain, and Steinlen, formed a community of graphic artists who were shaping the visual culture of the era. Their regular gatherings, perhaps at Montmartre cafés like Le Rat Mort, which was a known haunt for the staff of Le Courrier Français, would have been crucibles of creative exchange and social commentary. His teachers, Tony Robert-Fleury and Jules Joseph Lefebvre, connected him to the established academic tradition, while his engagement with contemporary illustrators and emerging modernists like Villon demonstrated his forward-looking perspective. One can also imagine him crossing paths with or being aware of the work of other prominent Montmartre figures like Pierre Bonnard or Édouard Vuillard of the Nabis group, who also engaged in graphic arts, or even the Fauvist Kees van Dongen, known for his vibrant depictions of Parisian society.

Public Commissions and Later Career

Beyond his easel paintings and graphic work, Widhopff also undertook public commissions. Notably, he was responsible for creating a series of decorative murals for the interior of the old Cirque-Théâtre (Circus-Theatre) in Limoges. These murals, characterized by their vibrant colors and lively depictions, showcased his ability to work on a large scale and to create art for public spaces. The choice of Widhopff for such a commission speaks to his reputation and his skill in creating engaging, dynamic compositions. These works, some of which have been preserved or documented, add another dimension to his artistic output.

Throughout his career, Widhopff continued to exhibit his work. He held a solo exhibition at the Galerie Eugène Blot in Paris in 1919, a significant venue that also showed works by Impressionist and Post-Impressionist masters. He also exhibited at the B. Well Gallery. These exhibitions provided opportunities for the public and critics to see a broader range of his paintings beyond his widely circulated illustrations.

Anecdotes and Persona: The Man Behind the Art

Anecdotes from the period paint a picture of Widhopff as a distinctive personality. The description of him possessing "Herculean strength" by Marcel Lamare was not just a comment on his art but likely also alluded to his physical presence or character. He was also known for his "legendary great beard," a striking feature that would have made him a recognizable figure in the cafes and studios of Montmartre. Such personal details contribute to the image of an artist who was not only talented but also a memorable character within his artistic community.

His active social life, implied by his involvement with journal staff and café society, suggests an artist who was engaged with his contemporaries and drew inspiration from the bustling urban environment around him. The life of a Parisian artist during the Belle Époque was often intertwined with the city's social and cultural rhythms, and Widhopff appears to have been fully immersed in this world.

Legacy and Rediscovery

David Ossipovitch Widhopff died in Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, a village northwest of Paris, on July 20, 1933. While he was a well-known figure during his lifetime, particularly for his illustrations, his name, like those of many talented artists of his era who did not become leading figures of major avant-garde movements, became somewhat less prominent in broader art historical narratives of the mid-20th century.

However, there has been a growing appreciation for artists who worked across different media and who captured the specific character of the Belle Époque. Widhopff's work is preserved in various public and private collections. The Musée des Beaux-Arts de Limoges, for instance, holds works by him, including studies related to his circus murals, acknowledging his contribution to the local cultural heritage. His paintings and drawings also appear at auctions, where they command interest from collectors of early 20th-century European art.

His contributions as an illustrator are particularly significant for understanding the visual culture of fin-de-siècle Paris. Magazines like Le Courrier Français were vital platforms for artists and played a crucial role in shaping public taste and opinion. Widhopff's prolific output for these journals makes him an important chronicler of his time. The renewed interest in graphic arts, poster design, and the social history of art has helped to bring figures like Widhopff back into focus.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Talent of the Belle Époque

David Ossipovitch Widhopff was an artist of considerable talent and versatility whose career spanned several key areas of artistic production in late 19th and early 20th-century Paris. From his academic training to his Salon exhibitions, and from his incisive caricatures in popular journals to his decorative public murals, he demonstrated a remarkable adaptability and a keen engagement with the artistic currents of his time.

His work provides a vivid window into the society, culture, and visual landscape of the Belle Époque. As a painter, he explored traditional genres with a confident and expressive touch. As an illustrator and caricaturist, he was a sharp-eyed observer and witty commentator on Parisian life, his drawings capturing the energy and characters of the era. His connections with prominent artists like Alphonse Mucha and his contributions to influential publications underscore his active role in the artistic milieu of his day. While perhaps not always accorded the same level of fame as some of his avant-garde contemporaries, David Ossipovitch Widhopff remains an important figure whose multifaceted contributions enrich our understanding of a vibrant and transformative period in art history. His legacy endures in his diverse body of work, which continues to engage and delight those who encounter it.