Henri-Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa stands as one of the most fascinating and distinctive figures in the landscape of late 19th-century European art. Born on November 24, 1864, and passing away prematurely on September 9, 1901, his life was as vibrant, tumultuous, and ultimately tragic as the Parisian world he so brilliantly captured. A pivotal artist within the Post-Impressionist movement, Lautrec’s work provides an unparalleled visual record of the Belle Époque in Paris, particularly its burgeoning, often gritty, entertainment and nightlife scenes centered around the district of Montmartre. His unique perspective, shaped by both his aristocratic heritage and his physical disabilities, allowed him to observe and depict his subjects with a blend of detachment, empathy, and incisive graphic power that remains compelling today. He was not merely a painter but a master draughtsman, printmaker, and arguably the father of the modern artistic poster.

Early Life and Formative Years

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was born into the highest echelons of the French aristocracy at the Hôtel du Bosc in Albi, Tarn, in the south of France. His parents, Comte Alphonse de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa and Adèle Tapié de Celeyran, were first cousins, a union not uncommon among noble families seeking to preserve lineage and fortune, but one that likely contributed to Henri's later health problems. The Toulouse-Lautrec family could trace its ancestry back nearly a millennium, counting the Counts of Toulouse among their forebears. This privileged background afforded Henri access to education and culture but also set him apart from the world he would later choose to inhabit and document.

His childhood, though privileged, was marred by congenital health issues. It is widely believed he suffered from a rare genetic disorder, possibly pycnodysostosis (sometimes informally dubbed "Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome") or a form of osteogenesis imperfecta. This condition affected his bone development. While his torso developed normally, his legs remained disproportionately short. His adult height reached only about 1.52 to 1.54 meters (around 5 feet). This condition was exacerbated by two separate accidents during his adolescence: at age 13, he fractured his right femur, and at 14, his left. These breaks failed to heal properly, effectively halting the growth of his legs.

Unable to participate in the traditional aristocratic pursuits like riding and hunting that his father excelled at, the young Henri found solace and purpose in art. His talent for drawing and painting emerged early, encouraged initially by his mother and relatives, including his uncle Charles and the animal painter René Princeteau, a friend of his father's. Art became his refuge and his primary means of engaging with the world. Recognizing his burgeoning talent and dedication, his family supported his artistic ambitions, a somewhat unusual path for a nobleman of his standing at the time. He received formal training, initially studying under Léon Bonnat in Paris in 1882. Bonnat's academic approach, however, did not suit Lautrec's temperament. He soon moved to the studio of Fernand Cormon, where he spent several years. Cormon's studio was a more liberal environment and a hub for young, aspiring artists. It was here that Lautrec encountered fellow students who would also make significant marks on art history, including Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin, and, most notably, Vincent van Gogh, with whom he formed a friendship.

Montmartre and the Bohemian Milieu

By the mid-1880s, Toulouse-Lautrec had fully embraced the life of an artist and gravitated towards Montmartre, the burgeoning artistic and entertainment quarter perched on a hill overlooking Paris. This district, with its windmills, cabarets, dance halls, studios, and cheap lodgings, was a magnet for artists, writers, performers, and a diverse population ranging from the working class to bohemians and pleasure-seekers. For Lautrec, Montmartre offered a world vastly different from the staid aristocratic circles of his upbringing. Here, his physical appearance was less of a barrier; the emphasis was on talent, wit, and originality. He found a sense of community and acceptance, establishing a studio and immersing himself completely in the area's unique atmosphere.

He became a fixture in the legendary establishments that defined Montmartre's nightlife. The Moulin Rouge, which opened in 1889, became one of his most frequent haunts and a primary source of inspiration. He was also a regular at Le Mirliton, the cabaret run by the singer and songwriter Aristide Bruant, whose sharp social commentary resonated with Lautrec. Other venues like the Folies-Bergère, the Moulin de la Galette, various cafés-concerts, circuses, and even the local brothels, became his extended studio. He didn't just observe this world; he participated in it, forming friendships and relationships with the performers, proprietors, and patrons who populated these spaces. His aristocratic title sometimes opened doors, but it was his genuine interest, sharp wit, and artistic talent that allowed him to truly connect with the denizens of this vibrant, often harsh, environment. This immersion provided him with the raw material for his art, allowing him to capture the energy, artificiality, glamour, and underlying melancholy of Parisian modern life with unparalleled authenticity.

Artistic Style and Influences

Toulouse-Lautrec is firmly placed within Post-Impressionism, a broad movement that emerged in the 1880s as a reaction against the perceived limitations of Impressionism. While Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir focused on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, often in outdoor settings, Post-Impressionists sought to imbue their work with greater emotional depth, symbolic meaning, or structural coherence. Lautrec, alongside contemporaries like Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Paul Cézanne, forged a highly individual path. His style is characterized by its strong emphasis on line, dynamic composition, and bold use of color, often applied in flat areas, coupled with a keen psychological insight into his subjects.

His draughtsmanship was exceptional. Lautrec possessed an uncanny ability to capture the essence of a person or a scene with a few swift, expressive lines. This linear quality is evident in his paintings, drawings, and especially his prints. He often distorted figures for expressive effect, elongating limbs or exaggerating features to convey movement, character, or caricature. His compositions were often unconventional, employing sharp diagonals, dramatic cropping, and unusual viewpoints, techniques that heightened the sense of immediacy and dynamism. He frequently depicted scenes under artificial light – the harsh glare of gaslight or early electricity in cabarets and theaters – which allowed for stark contrasts and vibrant, sometimes jarring, color palettes.

Two major influences are consistently cited in discussions of Lautrec's style. The first is the work of Edgar Degas, an artist Lautrec deeply admired. Like Degas, Lautrec was fascinated by modern urban life, particularly scenes of entertainment like the ballet, café-concerts, and circuses. He adopted Degas's penchant for asymmetrical compositions, cropped figures, and capturing subjects in seemingly unposed, natural moments. However, Lautrec's work often possesses a rawer energy and a more direct engagement with the sometimes sordid aspects of his subjects' lives compared to Degas's more detached observations.

The second key influence was Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which became highly fashionable in Paris during the late 19th century (Japonisme). Artists like Katsushika Hokusai and Kitagawa Utamaro captivated European artists with their flattened perspectives, bold outlines, asymmetrical compositions, and decorative use of color. Lautrec absorbed these elements, integrating them seamlessly into his own visual language. The influence is particularly evident in his posters and lithographs, with their emphasis on flat planes of color and strong contours, creating striking and memorable images perfectly suited for public display.

Master of the Poster

While a gifted painter, Toulouse-Lautrec arguably made his most revolutionary contribution in the field of printmaking, specifically lithography and poster design. In the late 19th century, advancements in color lithography transformed the streets of Paris into open-air galleries, with vibrant posters advertising everything from theatrical performances to consumer products. Lautrec seized upon this medium, elevating it from mere commercial advertising to a genuine art form. He understood the power of simplification and bold design needed to capture attention in a bustling urban environment.

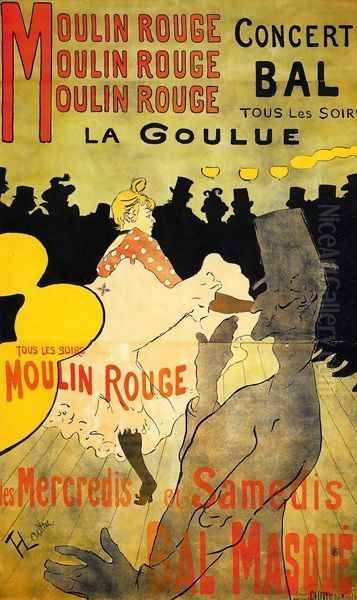

His first major poster, Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891), was an immediate sensation and cemented his reputation. Commissioned by the famous cabaret, the poster depicts the can-can dancer Louise Weber, known as La Goulue ("The Glutton"), and her partner Valentin le Désossé ("The Boneless One"). The dynamic composition, silhouetted figures, flat areas of color, and energetic lines perfectly captured the spirit of the Moulin Rouge. It was radically different from the more illustrative posters common at the time and demonstrated Lautrec's genius for distilling a complex scene into a powerful graphic statement.

Following this success, Lautrec received numerous commissions and produced around 30 posters that are now considered icons of the era. He created memorable images for performers like the singer Yvette Guilbert, instantly recognizable by her long black gloves and expressive gestures; the imposing Aristide Bruant, depicted in his signature black cape and red scarf for his performances at Les Ambassadeurs; and the dancer Jane Avril, whose ethereal, almost nervous energy he captured in several posters, including one for the Divan Japonais café-concert. These posters were not just advertisements; they were works of art that defined the visual identity of Parisian nightlife. Lautrec's approach profoundly influenced subsequent graphic design and poster art, demonstrating that commercial work could possess high artistic merit. His contemporaries in poster art included Jules Chéret and Alphonse Mucha, though Lautrec's style remained distinct in its sharp observation and lack of idealized sentimentality.

Depicting the Demimonde

A significant portion of Toulouse-Lautrec's oeuvre is dedicated to depicting the inhabitants of the Parisian demimonde – the world of entertainers, prostitutes, and those living on the fringes of respectable society. His portrayal of these figures was groundbreaking in its honesty and lack of moralizing. He approached his subjects not as exotic curiosities or objects of pity, but as individuals with their own lives, emotions, and relationships. His disability perhaps gave him a unique empathy for those who, like himself, existed outside the conventional norms of society.

He painted the stars of the Montmartre stage with an insider's knowledge. His portraits of La Goulue capture her boisterous energy, while his depictions of Jane Avril convey a more fragile, sophisticated persona. He documented the performances, the backstage moments, and the private lives of these figures. His series of paintings and prints featuring Yvette Guilbert focus on her unique performance style, emphasizing her gestures and expressions rather than conventional beauty.

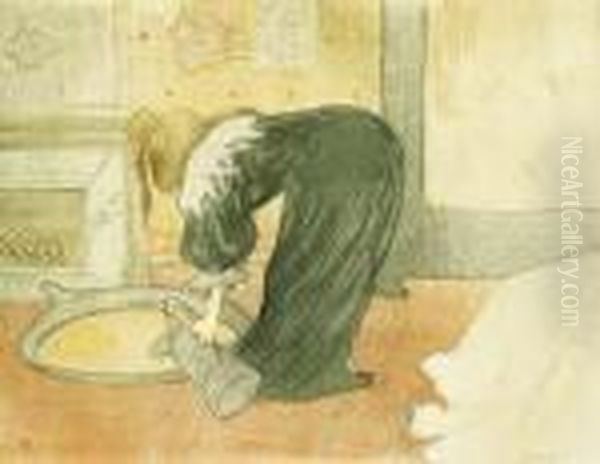

Lautrec's exploration of the world of prostitution was particularly notable. He spent considerable time in the maisons closes (licensed brothels) of Paris, not just as a client, but as an observer and even a temporary resident. He befriended many of the women, sketching and painting them during their off-hours, capturing moments of intimacy, boredom, fatigue, and camaraderie. The resulting works, such as the painting Salon at the Rue des Moulins (1894) and the lithographic series Elles (1896), offer an unvarnished glimpse into the daily lives of these women. He depicted them dressing, washing, waiting for clients, or simply resting, often highlighting the mundane reality rather than the sensational aspects of their profession. These works are remarkable for their sensitivity and psychological depth, presenting the women as complex human beings rather than mere stereotypes. This empathetic portrayal contrasted sharply with the often exploitative or sentimentalized depictions common at the time.

Key Works and Themes

Beyond his iconic posters and brothel scenes, Toulouse-Lautrec produced a rich body of paintings and drawings exploring various facets of Parisian life. At the Moulin Rouge (1892–1895) is one of his most ambitious paintings, a complex group portrait set within the famous cabaret. It features a cast of characters including dancers, patrons, and Lautrec himself seen in the background alongside his tall cousin and companion, Dr. Gabriel Tapié de Celeyran. The painting masterfully captures the artificial, electrically lit atmosphere of the venue, using jarring colors and tilted perspectives to convey the energy and perhaps the underlying tension of the scene.

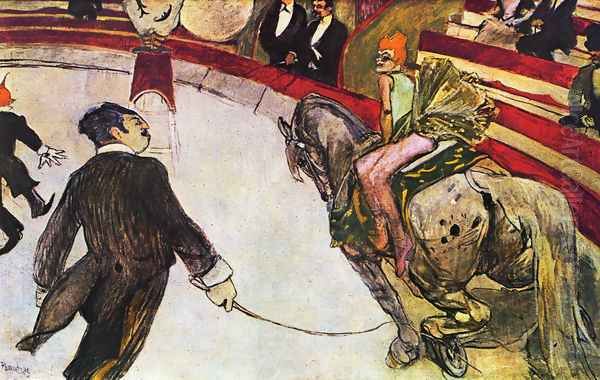

His interest extended beyond the nightlife. Works like The Laundress (1889) demonstrate his observation of working-class life, depicting a woman engaged in strenuous physical labor with dignity and realism. He was also drawn to the circus, capturing the skill and dynamism of performers in works like Equestrienne (At the Cirque Fernando) (1887-1888). Across his diverse subjects, recurring themes emerge: the spectacle of modern entertainment, the contrast between public performance and private reality, the effects of artificial light, the exploration of human psychology through gesture and expression, and an unflinching look at the social fabric of his time. He rarely painted traditional landscapes or still lifes, focusing almost exclusively on the human figure within its specific urban environment.

Personal Life, Health, and Relationships

Toulouse-Lautrec's personal life was deeply intertwined with his art and marked by the challenges of his health. Despite his aristocratic background, he largely eschewed high society, preferring the company of artists, writers, and the denizens of Montmartre. He was known for his sharp wit, intelligence, and often self-deprecating humor, which perhaps served as a defense mechanism against the stares and comments his appearance sometimes attracted. He formed close friendships, notably with his cousin Dr. Gabriel Tapié de Celeyran, who often accompanied him and appears in several paintings. He also maintained relationships with fellow artists and writers, navigating the complex social networks of bohemian Paris.

His relationships with women were complex and often centered around the figures he painted – dancers like Jane Avril and prostitutes he befriended. While he formed close bonds, there is little evidence of lasting romantic partnerships. His physical condition and perhaps his immersion in a world where relationships were often transactional may have contributed to this. His closest and most enduring relationship was arguably with his mother, Countess Adèle, who remained a steadfast supporter throughout his life, managing his affairs and preserving his legacy after his death.

Lautrec struggled significantly with alcoholism. He was known for his heavy drinking and even invented potent cocktails, like the infamous "Earthquake" (reportedly a mix of absinthe and cognac). His dependence on alcohol intensified over time, likely exacerbated by his chronic health problems and perhaps the emotional toll of his lifestyle and disability. It is also widely accepted that he contracted syphilis, a common affliction in the circles he frequented. These factors severely impacted his health in his later years. In 1899, following a collapse brought on by alcoholism, he was committed by his family to a sanatorium in Neuilly for several months. Even there, he continued to draw, producing a remarkable series of circus drawings from memory to prove his sanity and secure his release.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Toulouse-Lautrec worked during a period of intense artistic innovation in Paris. He was part of the Post-Impressionist generation that included Van Gogh, Gauguin, Seurat, and Cézanne, each reacting to Impressionism in their own way. While he shared their interest in subjective expression and formal experimentation, his focus on contemporary urban realism set him apart from Gauguin's exotic symbolism or Cézanne's structural analysis of nature. His closest artistic kinship was perhaps with Degas, who shared his fascination with modern life, movement, and unconventional compositions, though Lautrec's line is often considered more aggressive and his emotional tone more direct.

He was also aware of other contemporary movements. The Symbolists, such as Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, explored dreamlike, mythological, or literary themes, contrasting with Lautrec's grounding in observable reality. The Nabis group, including Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, shared Lautrec's interest in intimate interiors and decorative patterning, influenced by Japanese art, but often focused on more bourgeois domestic scenes. Lautrec's unique contribution was his unflinching portrayal of the specific milieu of Montmartre's entertainment world and demimonde. His work also intersected with the burgeoning Art Nouveau movement, particularly in his poster designs, although his style retained a grittier realism distinct from the more flowing, ornamental aesthetics of artists like Mucha. He exhibited his work alongside many of these artists, participating in the vibrant, often contentious, Parisian art scene through exhibitions like the Salon des Indépendants and Les XX in Brussels.

Later Years and Legacy

After his release from the sanatorium in 1899, Toulouse-Lautrec attempted to moderate his drinking and continued to work, traveling and producing portraits and other pieces. However, his health was irrevocably damaged. The combined effects of alcoholism and syphilis took their toll. In the summer of 1901, he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. He returned to his mother's estate, the Château Malromé, in the Gironde region. He died there on September 9, 1901, just a few months short of his 37th birthday.

Despite his tragically short life, Toulouse-Lautrec left behind a prolific and influential body of work, including over 730 paintings, nearly 300 watercolors, over 5,000 drawings, and some 350 prints and posters. His legacy is multifaceted. He is celebrated as one of the key figures of Post-Impressionism, whose unique style bridged the gap between the observational realism of Degas and the expressive intensity that would characterize later movements. His depictions of Parisian nightlife provide an invaluable historical and social document of the Belle Époque.

His most profound and lasting impact may be in the realm of graphic arts. He revolutionized poster design, demonstrating its potential as a powerful art form and influencing generations of graphic artists. His mastery of lithography pushed the boundaries of the medium. His work had a discernible influence on subsequent artists, including the young Pablo Picasso, whose early work in Paris clearly shows Lautrec's impact in both subject matter and style. Elements of his expressive line and bold color can also be seen as precursors to Fauvism (Henri Matisse) and German Expressionism (Egon Schiele, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner).

Today, his works are housed in major museums worldwide. The largest collection resides in his hometown at the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi, established largely through the efforts of his mother. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec remains a figure of enduring fascination – an artist whose aristocratic background and physical limitations gave him a unique vantage point from which to observe and record the vibrant, complex, and often contradictory world of turn-of-the-century Paris with unparalleled honesty, empathy, and graphic brilliance.