Henri-Gabriel Ibels (1867-1936) stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the vibrant Parisian art scene of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A multifaceted talent, Ibels was a painter, printmaker, illustrator, poster artist, and writer, whose work captured the pulse of his era with a distinctive graphic style. As a founding member of the influential Post-Impressionist group Les Nabis, he contributed to a pivotal shift in modern art, moving away from naturalistic representation towards a more subjective, symbolic, and decorative approach. His keen observations of Parisian society, from its bustling boulevards and smoky cafés to the spectacle of the circus and the intensity of the boxing ring, provide a vivid testament to the Belle Époque.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Born in Paris on November 30, 1867, Henri-Gabriel Ibels was immersed from a young age in the cultural dynamism of the French capital. This environment would profoundly shape his artistic sensibilities and thematic choices. His formal artistic training began in 1887 when he enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian. This private art school was a popular alternative to the more conservative École des Beaux-Arts, attracting many aspiring artists who sought a more liberal and experimental atmosphere.

At the Académie Julian, Ibels studied alongside figures who would become his lifelong colleagues and fellow innovators, most notably Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard. These friendships and shared artistic explorations were crucial in the development of his early style and his eventual involvement with Les Nabis. The Académie Julian, under the guidance of instructors like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury, provided a solid grounding in academic technique, but it was also a crucible for new ideas, allowing students like Ibels, Bonnard, and Vuillard to explore directions beyond traditional academicism.

The Genesis of Les Nabis

The late 1880s were a period of artistic ferment in Paris. Impressionism had revolutionized painting, but a new generation was already seeking different modes of expression. In 1888, Paul Sérusier, another student at the Académie Julian, returned from Pont-Aven in Brittany, where he had painted a small, abstract landscape on a cigar box lid under the direct guidance of Paul Gauguin. This painting, known as The Talisman, became a foundational object for a group of young artists.

Gauguin's advice to Sérusier was radical: "How do you see these trees? They are yellow. So, put in yellow; this shadow, rather blue, paint it with pure ultramarine; these red leaves? Put in vermilion." This emphasis on pure color, subjective interpretation, and the simplification of forms into decorative patterns – a style Gauguin termed Synthetism – resonated deeply with Ibels and his peers. In 1889, Ibels, Bonnard, Vuillard, Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel, and others formally coalesced into a group they called "Les Nabis," a Hebrew word meaning "prophets." They saw themselves as heralding a new era in art.

Ibels' Distinctive Voice within Les Nabis

While Les Nabis shared common goals – a rejection of Impressionistic naturalism, an interest in Symbolism, a desire to break down the barriers between fine and applied arts, and an embrace of decorative qualities – each member developed a unique artistic personality. Ibels quickly distinguished himself within the group, earning the nickname "le Nabis journaliste" for his keen eye for contemporary life and his ability to capture its essence with graphic immediacy.

His style was characterized by strong, bold outlines, flattened perspectives, and a simplification of forms, often reminiscent of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which were a major source of inspiration for many artists of the period, including Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and Vincent van Gogh. Ibels, like his Nabis colleagues, was particularly drawn to the compositional innovations, asymmetrical arrangements, and decorative use of color found in the works of masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige. He also absorbed lessons from Impressionism, particularly its focus on modern urban subjects, but translated these into a more stylized and graphic idiom. His work often carried a blend of realism in its subject matter and symbolism in its evocative power.

The Spectacle of Parisian Life: Ibels' Thematic Universe

Ibels' art is inextricably linked to the city of Paris. He was a dedicated observer of its myriad scenes and characters, particularly those associated with popular entertainment and everyday life. His canvases, prints, and illustrations teem with the energy of Parisian streets, the intimate ambiance of cafés, the dazzling allure of the circus, and the raw physicality of the boxing ring. These were subjects also favored by contemporaries like Jean Béraud and Jean-Louis Forain, but Ibels approached them with the Nabis' characteristic emphasis on pattern, simplified form, and subjective color.

The café-concerts and circuses of Montmartre, such as the Cirque Fernando (later Cirque Medrano), provided rich material. He captured the performers, the audience, and the unique atmosphere of these venues. His depictions often focused on the human element, conveying the emotions and social dynamics at play. He was particularly interested in the lives of ordinary Parisians, including the working class, and his work often carried an undercurrent of social observation, if not always overt commentary. This focus on the "spectacle" of modern life aligned him with artists like Georges Seurat, whose Circus Sideshow also explored similar themes, albeit with a different, Pointillist technique.

Master of the Poster and Printmaking

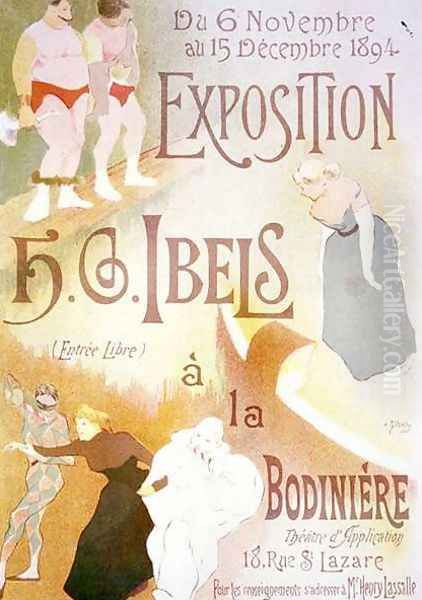

The late 19th century witnessed a golden age of poster art, fueled by advancements in color lithography pioneered by artists like Jules Chéret. Posters became a vibrant form of public art, transforming the streets of Paris into open-air galleries. Ibels was a significant contributor to this movement, creating striking posters for theaters, cabarets, and other events. His designs were notable for their bold graphics, dynamic compositions, and effective use of typography, making them highly visible and memorable.

Ibels was a prolific printmaker, particularly skilled in lithography. This medium allowed him to explore his graphic sensibilities, creating works with rich blacks, subtle tonal variations, and expressive lines. His prints often depicted the same themes as his paintings – scenes of Parisian life, portraits, and theatrical subjects. He contributed to important print portfolios of the era, including L'Estampe originale and Les Maîtres de l'Affiche (Masters of the Poster). The latter, published by Jules Chéret's printing house Imprimerie Chaix between 1895 and 1900, reproduced smaller versions of the era's best posters by artists such as Chéret himself, Alphonse Mucha, Théophile Steinlen, and, of course, Ibels and his close associate Toulouse-Lautrec.

His work for the theater was extensive. He designed posters, programs, and even stage sets for avant-garde theatrical productions, collaborating with institutions like the Théâtre Libre, founded by André Antoine, and the Théâtre de l'Art, run by Paul Fort. These theaters were at the forefront of Symbolist drama, and Ibels' visual style complemented their innovative and often anti-naturalistic productions.

A Close Bond: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Among Ibels' contemporaries, his relationship with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was particularly significant. Both artists shared a deep fascination with the demimonde of Paris – its cabarets, dance halls, and brothels – and both developed highly individual graphic styles well-suited to poster art and illustration. They were friends and collaborators, often frequenting the same Montmartre establishments and influencing each other's work.

While Toulouse-Lautrec is perhaps more widely known today, Ibels was a respected peer whose contributions to the visual culture of the time were substantial. They both possessed an acute ability to capture character and movement with a few deft lines, and their work often shared a similar sense of immediacy and psychological insight. Their collaboration extended to various publishing projects, and their artistic dialogue undoubtedly enriched both their oeuvres. The shared interest in depicting performers, such as the dancer Jane Avril or the singer Yvette Guilbert, highlights their common artistic ground, though each brought his unique perspective.

Social Conscience and Political Engagement

Ibels was not an artist confined to an ivory tower; he was engaged with the social and political currents of his time. His interest in the lives of ordinary people and the working class sometimes translated into works with a clear social conscience. This engagement became more explicit through his contributions to satirical and politically oriented publications.

Notably, Ibels created cartoons and illustrations for the anarchist journal Le Père Peinard, founded by Émile Pouget (not Pierre Emile, as sometimes mistakenly cited). This publication was known for its radical views and its use of vernacular language to reach a working-class audience. Ibels' graphic work for Le Père Peinard demonstrated his ability to use his art for pointed social critique, aligning him with other socially conscious artists of the period like Théophile Steinlen, who also contributed to leftist publications.

His involvement in the Dreyfus Affair further underscores his political engagement. This divisive scandal, which polarized French society in the 1890s and early 1900s, saw Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer, falsely accused of treason. Ibels, like many intellectuals and artists including Émile Zola, Claude Monet, and Camille Pissarro, sided with the Dreyfusards, who believed in Dreyfus's innocence and fought for his exoneration. His lithograph Le coup de l'éponge (The Sponge Wipe, c. 1899) is a powerful commentary related to the Affair, symbolically depicting the attempt to cleanse or absolve the military and the church of their roles in the injustice. This contrasted with artists like Edgar Degas and Auguste Renoir, who were anti-Dreyfusards.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

While a comprehensive list of Ibels' works is extensive, several pieces stand out as representative of his style and concerns:

Le coup de l'éponge (c. 1899): This color lithograph, mentioned above, is a potent example of Ibels' political art. It features a figure representing the Church attempting to wipe clean a slate held by a military figure, alluding to the cover-ups and injustices of the Dreyfus Affair. The strong outlines and bold, somewhat somber colors are typical of his printmaking.

Exposition de l'Affiche (1897): This poster, designed for an exhibition of posters, showcases Ibels' mastery of the medium. It features a dynamic composition with figures interacting with posters, rendered in his characteristic flattened style and vibrant colors, effectively advertising the event itself.

Mevisto (Plate 78 from Les Maîtres de l'Affiche): This poster, likely for a cabaret performer or act, captures the theatricality and allure of Parisian nightlife. The figure of Mevisto, perhaps a Mephistophelean character, is rendered with bold, dark contours and a dramatic use of color, typical of Ibels' poster work and his ability to create an immediate visual impact.

Illustrations for La Danse and Music: His work for avant-garde theatrical programs, such as those for plays like La Danse and Music, demonstrates his ability to create imagery that captured the symbolic and often abstract nature of these performances. These illustrations often featured simplified figures and a focus on mood and atmosphere.

Scenes of the Circus and Boxing: Throughout his career, Ibels produced numerous paintings and prints depicting circus performers, clowns, and boxers. These works are characterized by their dynamic compositions, capturing the movement and energy of the subjects, as well as a sense of empathy for the performers.

Enduring Influences and Artistic Dialogue

Ibels' artistic development was shaped by a confluence of influences. The impact of Japanese ukiyo-e prints is undeniable, evident in his use of asymmetrical compositions, flat planes of color, strong outlines, and the cropping of figures. This "Japonisme" was a widespread phenomenon, but Ibels integrated it seamlessly into his depictions of contemporary Parisian life.

The legacy of Paul Gauguin was, of course, central to the Nabis. Gauguin's Synthetist principles – emphasizing memory, imagination, and the emotional use of color and line over direct observation – provided the theoretical underpinning for the group. Ibels adopted these principles, applying them to his urban subjects rather than the more exotic or rustic scenes favored by Gauguin or Sérusier.

While reacting against Impressionism's focus on fleeting optical effects, Ibels and the Nabis still built upon its liberation of color and its embrace of modern life as a worthy subject for art. Artists like Edgar Degas, with his depictions of dancers, café scenes, and racetracks, and Édouard Manet, with his portrayals of urban leisure, had paved the way for artists like Ibels to explore similar themes, albeit with a new stylistic vocabulary.

Within the Nabis, there was constant artistic dialogue. The close-knit nature of the group, with regular meetings at Paul Ranson's studio (dubbed "The Temple"), fostered an environment of shared experimentation. Ibels' graphic strength and focus on social observation complemented the more intimate, domestic scenes of Bonnard and Vuillard (the "Intimists"), the religious and symbolic works of Maurice Denis, and the decorative designs of Ranson. Félix Vallotton, another Nabis member known for his stark woodcuts and incisive social commentary, shared some common ground with Ibels in terms of graphic power and critical observation.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

The Nabis group began to disperse around 1900, as individual members pursued their own artistic paths. Ibels continued to work as an illustrator, printmaker, and painter. He remained active in the Parisian art world, exhibiting his work and contributing to various publications. He also dedicated time to writing, further showcasing his versatile talents.

Henri-Gabriel Ibels passed away in Paris in February 1936. While perhaps not achieving the same level of posthumous fame as some of his Nabis colleagues like Bonnard or Vuillard, or his friend Toulouse-Lautrec, his contributions to French art at the turn of the century were significant and multifaceted.

His legacy lies in his distinctive graphic style, which bridged the gap between fine art and popular illustration. He was a pioneer in poster design and a master of lithography, creating images that were both aesthetically compelling and culturally resonant. As "le Nabis journaliste," he provided a unique and insightful visual record of Parisian life during the Belle Époque, capturing its energy, its characters, and its social complexities. His work influenced subsequent generations of illustrators and graphic artists, and his role as a founding member of Les Nabis secures his place in the history of modern art as an artist who sought to infuse art with new meaning, decorative power, and a profound connection to the contemporary world. His engagement with social and political issues also marks him as an artist who believed in the power of art to reflect and comment upon society.

Conclusion

Henri-Gabriel Ibels was an artist of remarkable versatility and keen observation. From his formative years at the Académie Julian to his pivotal role in the Nabis movement, and throughout his career as a chronicler of Parisian life, he forged a distinctive artistic path. His bold, graphic style, influenced by Japanese prints and the tenets of Synthetism, was perfectly suited to the dynamic subjects he favored – the theater, the circus, the café, and the bustling city streets. As a printmaker and poster artist, he made significant contributions to the visual culture of his time, while his socially conscious works reveal an artist deeply engaged with the world around him. Ibels remains an important figure for understanding the artistic innovations of the late 19th century and the vibrant cultural tapestry of Belle Époque Paris.