David Oyens (1842-1902) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century European art. A Dutch painter by birth, he, alongside his identical twin brother Pieter Oyens, carved out a distinctive niche primarily within the vibrant art scene of Brussels. Their shared life and artistic journey, characterized by intimate genre scenes, meticulous still lifes, and insightful portraits, offer a fascinating window into the period's prevailing realist tendencies, subtly infused with a personal warmth and gentle humor. This exploration delves into the life, work, artistic milieu, and lasting legacy of David Oyens, a painter whose canvases capture the quiet dignity and nuanced moments of everyday existence.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations in Amsterdam

David Oyens was born in Amsterdam on July 29, 1842, into a prosperous family. His father was a successful banker, and it was initially anticipated that David and his twin brother, Pieter, would follow a similar path into the world of finance. However, from a young age, both brothers displayed a profound passion and talent for drawing and painting. This artistic calling proved stronger than familial expectations, and they ultimately chose to dedicate their lives to art, a decision that would lead them away from the counting houses of Amsterdam to the bohemian studios of Brussels.

Their early artistic education, though not extensively documented in the provided information, would have likely involved private instruction or attendance at local drawing academies in Amsterdam. The artistic environment of the Netherlands in the mid-19th century was still deeply influenced by its Golden Age masters. The legacy of painters like Rembrandt van Rijn for portraiture and psychological depth, Johannes Vermeer for his serene interior scenes and mastery of light, and numerous genre painters like Jan Steen or Pieter de Hooch for their depictions of daily life, would have formed an inescapable backdrop for any aspiring Dutch artist. This grounding in a tradition that valued realism, meticulous detail, and the quiet observation of human life undoubtedly shaped the Oyens brothers' artistic sensibilities.

The Move to Brussels: A Shared Studio and Artistic Development

In the 1860s, seeking a more dynamic and perhaps less tradition-bound artistic environment, David and Pieter Oyens made the pivotal decision to move to Brussels. The Belgian capital was, at this time, a burgeoning center for the arts, attracting artists from across Europe. It was a city where new artistic ideas were being debated and where realism, in particular, was finding fertile ground. Here, the brothers enrolled in the studio of Jean-François Portaels (1818-1895), a prominent Belgian painter and influential teacher. Portaels, known for his Orientalist scenes and portraits, had himself studied under Paul Delaroche in Paris and was a key figure in Belgian academic art, though his teaching also allowed for the development of more individual styles.

Under Portaels' tutelage, David and Pieter honed their skills. They established a shared studio, a common practice for artists, but in their case, it was a space that fostered an almost symbiotic artistic relationship. They worked in close proximity, often serving as models for one another, and developed styles so remarkably similar that it became a talking point, even a source of gentle confusion. Their shared life extended deeply into their artistic practice, creating a unique collaborative, yet individual, artistic output. The Brussels art scene was also home to or frequented by influential figures like Gustave Courbet, the standard-bearer of French Realism, whose impact was felt across Europe, and Belgian realists such as Constantin Meunier, known for his depictions of industrial labor, and Henri de Braekeleer, who specialized in intimate, Vermeer-like interiors.

Artistic Style: Realism, Intimacy, and Light

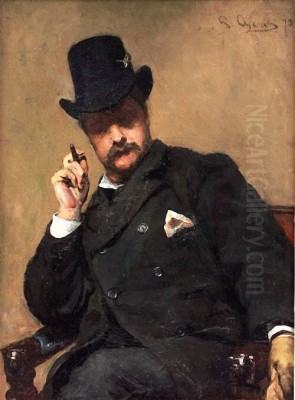

David Oyens, in concert with his brother, specialized in genre scenes, particularly those set within the confines of the artist's studio or quiet domestic interiors. Their work also encompassed portraits and still lifes. The defining characteristic of David's style was its refined realism, a meticulous attention to detail, and a subtle, often warm, depiction of light and atmosphere. His paintings exude a sense of tranquility and introspection, capturing fleeting moments of everyday life with sensitivity and grace.

The influence of 17th-century Dutch masters like Johannes Vermeer and the 18th-century French painter Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin is palpable in David Oyens' work. From Vermeer, one can see the preoccupation with light, particularly how it falls upon figures and objects within an interior space, creating a sense of stillness and imbuing ordinary scenes with a quiet poetry. From Chardin, there is an appreciation for the beauty of simple objects, the textures of materials, and the dignity of domestic life. David Oyens, however, was not merely an imitator; he absorbed these influences and filtered them through a 19th-century sensibility, often adding a touch of gentle humor or a narrative element that spoke to contemporary life.

His palette was generally subdued, favoring earthy tones, soft grays, and warm browns, which contributed to the intimate and often contemplative mood of his paintings. The brushwork was typically smooth and controlled, allowing for a high degree of finish and a clear rendering of form and texture. While firmly rooted in realism, his work sometimes hinted at a more modern sensibility in its composition or the psychological portrayal of his subjects.

Representative Works: Capturing Moments of Contemplation

Several works exemplify David Oyens' artistic concerns and stylistic approach. Young Woman Reading in the Studio (1901) is a prime example. In this painting, Oyens masterfully uses light and color to convey the quiet absorption of the young woman in her book. The light, perhaps from a nearby window, gently illuminates her, highlighting the textures of her clothing and the pages of her book, while the surrounding studio is rendered in softer, more muted tones. The composition, possibly employing principles like the golden ratio as suggested, creates a harmonious and balanced image that draws the viewer into the subject's contemplative state. The work speaks to the quiet intellectual pursuits and the intimate atmosphere of the studio.

Another significant piece mentioned is The Artist in His Studio reading l'Art Moderne. This title itself is revealing, suggesting an engagement with contemporary art discourse. The depiction of a figure, likely female, engrossed in a publication titled "Modern Art" within the artist's workspace, points to the intellectual currents of the time and the artist's own awareness of evolving artistic trends. The "abstract effect" noted in its description might refer to a simplification of forms, a particular handling of paint, or a focus on pattern and color that moves slightly beyond strict academic realism, perhaps hinting at an awareness of movements like Impressionism, even if his core style remained realist. Artists like Edgar Degas and Berthe Morisot in France were contemporaneously exploring themes of modern life and interior scenes, often with a focus on women reading or engaged in quiet activities, though their stylistic approaches differed.

The Oyens brothers often depicted themselves and their models within their studio, capturing the everyday reality of artistic life with a touch of humor and informality. These scenes provide valuable insights into the working environment of 19th-century artists and reflect the broader realist aim of portraying life as it was, without idealization.

The Oyens Twins: A Unique Artistic Symbiosis

The relationship between David and Pieter Oyens is one of the most distinctive aspects of their story. As identical twins, their physical resemblance was striking, and this similarity extended profoundly into their artistic output. They shared a studio, often collaborated by posing for each other, and developed styles that were, by all accounts, incredibly difficult to distinguish. It is said that even their wives sometimes struggled to tell their paintings—or indeed, the artists themselves—apart. One anecdote recounts David's wife, Betsy, mistakenly engaging in a conversation with Pieter, believing him to be her husband, and subsequently asking Pieter to have David visit less frequently to avoid such confusion.

This near-identical artistic vision is rare in art history. While many artistic families and partnerships exist, the Oyens brothers' case is exceptional due to their twinship and the resulting stylistic mirroring. Their signatures offered one of the few clues: David typically signed his work with his full name or simply "David Oyens," while Pieter often added "Piet" or signed "Pieter Oyens." Despite this close artistic bond, they were individuals with their own lives. David married Auguste Oudemans in 1866, a union that initially caused some adjustment for Pieter, who was deeply attached to his brother. However, their fraternal bond endured.

Their shared approach often involved capturing spontaneous moments, sometimes with a humorous undertone, reflecting the lively atmosphere of their studio and the bohemian circles of Brussels. This approach aligned with the modern spirit advocated by figures like the French writer Charles Baudelaire, who called for artists to depict the "heroism of modern life," and the painter Gustave Courbet, whose realism challenged academic conventions.

Interactions with Contemporaries and the Brussels Art Scene

David Oyens and his brother were active participants in the Brussels art world. They were part of a generation of artists in Belgium who were moving away from Romanticism and strict academicism towards various forms of Realism and, later, Impressionism and Symbolism. They would have been aware of, and likely interacted with, other prominent Belgian artists of the time. These included figures like Edouard Agneessens (1842-1885), a contemporary known for his portraits and genre scenes, Henri Van der Hecht (1841-1901), a landscape painter associated with the School of Tervuren (a Belgian equivalent to the Barbizon School), and Xavier Mellery (1845-1921), known for his introspective and melancholic depictions of interiors and allegorical subjects.

The Oyens brothers' work, with its focus on intimate realism, found a receptive audience. They exhibited their paintings regularly, including at the prestigious Brussels Salon, where their work received critical attention. The critic Camille Lemonnier, a significant voice in Belgian art and literature, praised their paintings. David Oyens also painted a portrait of Edmond Picard, another influential lawyer, writer, and art patron in Brussels, indicating their integration into the city's cultural elite.

While their primary sphere was Brussels, their reputation extended beyond. Their participation in the 1889 Paris World's Fair (Exposition Universelle), where they received an honorable mention, demonstrates their recognition on an international stage. This was the same exposition for which the Eiffel Tower was built, a major cultural event that showcased art and industry from around the world. To receive an award there was a significant achievement, placing them in the company of many leading artists of the era, such as Claude Monet and Auguste Rodin, who also exhibited.

The artistic currents of the time were diverse. While the Oyens brothers adhered to a form of realism, Impressionism was making significant inroads, with artists like Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley having already established the movement in France. Neo-Impressionism, with pioneers like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, was also emerging. While David Oyens' style did not fully embrace these avant-garde movements, his work's emphasis on light and capturing fleeting moments shows an awareness of the changing artistic landscape. His focus on "modern life" themes, such as reading contemporary art journals, also aligns with the broader modernist impulse.

Later Years, Declining Health, and Untimely Death

David Oyens married for a second time in 1893, to Catherine Elisabeth "Betsy" Voûte. However, around this period, his health began to deteriorate. The exact nature of his illness is not specified in the provided information, but it was serious enough to compel him to leave the vibrant artistic hub of Brussels. In 1896, seeking a quieter environment or perhaps better care, he moved to Arnhem, a city in the Netherlands.

Despite the change in surroundings, his health did not recover. David Oyens passed away in Brussels (the provided text mentions he died in Brussels, though he had moved to Arnhem; this might indicate he returned to Brussels for care or at the very end) on February 11, 1902, at the age of 60. His death was a profound blow to his twin brother, Pieter. The two had shared not just a life but an artistic soul. Pieter was reportedly devastated by David's passing, his own health declining rapidly in its wake. He struggled to recover from the loss and, tragically, died later that same year, in August 1902. Pieter was buried next to David, a final testament to their inseparable bond.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

In the immediate aftermath of their deaths, and for some decades following, the work of David and Pieter Oyens, like that of many realist painters of their generation who did not fully embrace later avant-garde movements, may have been somewhat overshadowed. However, their contribution to 19th-century Dutch and Belgian art remains significant. They represent a particular strand of realism that is intimate, observant, and imbued with a gentle humanity. Their studio scenes offer a unique glimpse into the life of artists, while their portraits and still lifes demonstrate a high level of technical skill and sensitivity.

The very uniqueness of their twinship and the remarkable similarity of their artistic output make them a fascinating case study in art history. They are a rare example of identical twin painters achieving professional success and recognition while working in such close stylistic harmony.

In more recent times, there has been a renewed appreciation for their work. Exhibitions, such as those mentioned as occurring in 2008 and 2010, have helped to bring their paintings back into the public eye and allowed for a re-evaluation of their artistic achievements. These reassessments highlight their skill in capturing the nuances of light and atmosphere, their insightful portrayal of character, and their ability to find beauty and interest in the everyday. Their work is held in various museum collections, particularly in the Netherlands and Belgium, ensuring their legacy endures.

David Oyens, alongside his brother Pieter, carved out a unique space in the art of the late 19th century. Their dedication to a refined realism, their focus on the intimate moments of life, and their shared artistic journey distinguish them. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of their contemporaries like Vincent van Gogh (a fellow Dutchman whose career took a radically different path) or the French Impressionists, David Oyens' art possesses a quiet charm and enduring quality. He was a master of his craft, a keen observer of human nature, and a painter whose works continue to resonate with viewers for their honesty, warmth, and technical finesse, reflecting the rich artistic dialogue between the Netherlands and Belgium in an era of significant cultural transformation. His paintings stand as a testament to a life dedicated to art, shared in an unparalleled bond with his twin, and contributing to the diverse narrative of European realism.