Boris Dmitrievich Grigoriev stands as a significant, if sometimes enigmatic, figure in the annals of early 20th-century art. A painter, graphic artist, and writer, he navigated the turbulent currents of Russian modernism and the émigré experience, leaving behind a body of work characterized by its intense psychological depth, distinctive stylistic flair, and an enduring preoccupation with the essence of Russian identity. His life, spanning from the twilight of Imperial Russia to the eve of World War II in Europe, was one of constant artistic exploration and personal upheaval.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born on July 11, 1886, in Rybinsk, a town on the Volga River, Boris Grigoriev's early life was marked by a certain ambiguity that perhaps fueled his later artistic inquiries into character and identity. He was the illegitimate son of Dmitry Grigoriev, a respected local official and bank manager, and Klara von Lindenberg, a woman of Swedish descent. This mixed heritage, Russian and Scandinavian, may have contributed to his unique perspective, an ability to see Russia both from within and with a degree of external observation. He was later formally adopted by his biological father.

His artistic inclinations manifested early. His formal training began at the prestigious Stroganov School of Art and Industry in Moscow, which he attended from 1903 to 1907. The Stroganov, known for its emphasis on applied arts as well as fine arts, provided a solid foundation. However, Grigoriev sought a more academic and perhaps more challenging environment, leading him to the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg.

The St. Petersburg Crucible and Emerging Affiliations

From 1907 to 1912, Grigoriev immersed himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of St. Petersburg, then the cultural heart of the Russian Empire. At the Imperial Academy, he studied under influential figures such as Aleksandr Kiselyov, a landscape painter, and Dmitry Kardovsky, a renowned painter and stage designer known for his historical scenes and masterful draftsmanship. Abram Arkhipov, another of his instructors, was celebrated for his depictions of Russian peasant life, a theme that would resonate deeply with Grigoriev.

Despite the academic setting, Grigoriev was a restless spirit, drawn to the burgeoning avant-garde movements. His time at the Academy was not without friction; he was reportedly expelled for his overly innovative tendencies, a testament to his burgeoning independent vision that chafed against rigid academicism. This rebellious streak led him to associate with more progressive artistic circles.

In 1908, while still a student, Grigoriev became a member of the "Union of Impressionists," a group that, despite its name, encompassed a broader range of post-impressionistic tendencies. His involvement with this group signaled his early alignment with modernist currents. A pivotal moment in his early career was his brief sojourn to Paris around 1911-1912, where he attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. This experience exposed him directly to the latest developments in French art, most notably the profound influence of Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to form and composition left an indelible mark on Grigoriev's evolving style.

Upon his return to St. Petersburg, Grigoriev became increasingly involved with the "Mir Iskusstva" (World of Art) movement, formally joining in 1913. This influential group, which included luminaries like Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, and Konstantin Somov, and was famously associated with the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, championed artistic synthesis, aestheticism, and a revival of interest in Russian folk art and 18th-century culture, while also embracing Western European artistic innovations. Grigoriev's participation in their exhibitions solidified his position within the Russian avant-garde.

The "Raseya" Cycle and the Faces of Russia

The period leading up to and immediately following the Russian Revolution of 1917 was intensely productive for Grigoriev. It was during this time that he embarked on one of his most significant artistic endeavors: the "Raseya" (Russia) cycle of paintings and drawings, created primarily between 1916 and 1918. This series was a profound and often unsettling exploration of the Russian peasantry and the "Russian soul."

Grigoriev's peasants were not idealized figures of pastoral romance. Instead, they were depicted with a stark, almost brutal honesty, their faces etched with hardship, resilience, and a deep, often inscrutable, inner life. Works like "The Village" (1917) and numerous portraits from this period capture the raw, elemental character of rural Russia. He sought to convey the perceived spiritual essence and enduring strength of the common people, even amidst poverty and social upheaval. His figures often possess an iconic, almost monumental quality, their gaze direct and penetrating.

His style during this period was characterized by strong, angular lines, a somewhat muted but expressive color palette, and a focus on the psychological intensity of his subjects. There's a palpable tension in these works, a sense of a world on the brink of profound change. The "Raseya" series established Grigoriev as a powerful and original voice, capable of capturing the complex and often contradictory nature of his homeland.

Portraiture and Theatrical Connections

Alongside his thematic cycles, Grigoriev was a highly sought-after portraitist. His ability to penetrate the sitter's psychology and render it with a distinctive, modernist edge made him popular among the artistic and intellectual elite. He painted portraits of many prominent figures, including the writer Maxim Gorky and the composer Sergei Rachmaninoff.

A particularly notable portrait from this era is that of the innovative theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold, completed around 1916. Grigoriev captured Meyerhold's dynamic and somewhat theatrical personality, reflecting the director's own avant-garde approach to stagecraft. This connection to the theatre world was not isolated; Grigoriev was part of a vibrant cultural scene in St. Petersburg that included writers like Velimir Khlebnikov and Anna Akhmatova, and fellow artists such as Sergey Sudeikin, who was also known for his theatrical designs. These interactions fostered a rich cross-pollination of ideas. His work "In the Circus" (1918) also demonstrates his interest in performance and spectacle, themes popular among avant-garde artists.

Emigration and the Parisian Years

The Bolshevik Revolution and the ensuing Civil War dramatically altered the course of Grigoriev's life and career. Like many artists and intellectuals who felt alienated by the new regime or feared for their future, Grigoriev chose emigration. In 1919, he managed to leave Russia, traveling first through Finland and Germany before settling in Paris, which became his primary base for the remainder of his life.

In Paris, Grigoriev quickly integrated into the émigré community and the broader international art scene. He became part of the bohemian artistic life of Montparnasse, a melting pot of creative talents from around the world. Artists like Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, and Chaim Soutine were his contemporaries in this vibrant environment, though the extent of his direct interactions with such figures varied. He continued to exhibit, and his work was shown at prestigious venues.

Despite living abroad, Russia remained a central theme in Grigoriev's art. He produced works that revisited Russian motifs, often imbued with a sense of nostalgia or critical reflection. His "Intimité" series, for example, explored more personal and introspective themes, but the Russian character often subtly permeated these compositions. He also traveled extensively, undertaking trips to the United States and South America, where he lectured and exhibited, seeking new audiences and inspiration.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Grigoriev's artistic style is not easily categorized under a single label. It was a dynamic synthesis of various influences, filtered through his unique sensibility. Early on, Impressionistic touches were evident, particularly in his handling of light and color. However, his work soon gravitated towards a more expressive and structurally rigorous approach.

The influence of Paul Cézanne is undeniable, especially in Grigoriev's emphasis on form and the underlying geometry of his compositions. This can be seen in the way he constructed his figures and landscapes, giving them a sense of solidity and weight. Elements of Expressionism are also prominent, particularly in the emotional intensity and psychological depth he conveyed, often through distorted or exaggerated features and a bold, sometimes unsettling, use of line.

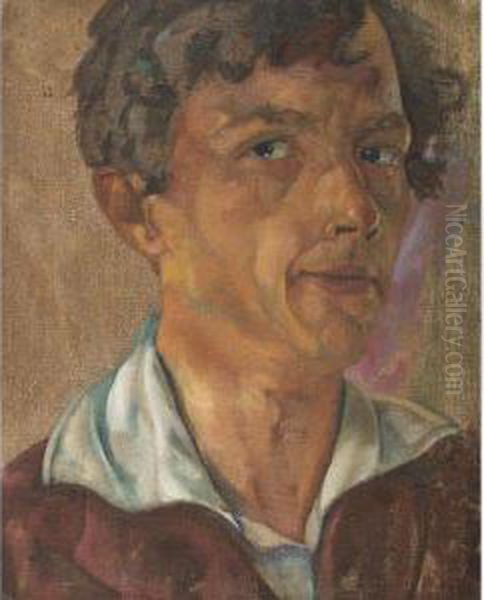

While not strictly a Cubist, Grigoriev certainly absorbed some of the formal innovations of Cubism, particularly its fragmentation of form and exploration of multiple perspectives, which he adapted to his own expressive ends. His draftsmanship was exceptional, characterized by a sharp, incisive line that defined forms with clarity and vigor. His color palettes could range from the somber and earthy tones of his "Raseya" series to brighter, more vibrant hues in his later works, always employed to enhance the emotional impact of the subject. Works like "Woman Washing Her Hair" (1917) and his "Self-Portrait" (1914) showcase his evolving mastery of form and psychological portrayal.

Literary Pursuits and Broader Cultural Impact

Beyond his prolific output as a painter and graphic artist, Boris Grigoriev also possessed literary talents. He authored a novel titled "Yunye Luchi" (Young Rays), which further demonstrated his multifaceted creative intellect and his engagement with the cultural currents of his time. This foray into literature underscores his identity as an artist deeply embedded in the broader intellectual life of the Russian avant-garde, where the boundaries between different artistic disciplines were often fluid.

His early association with the "No Teacher" movement, which he reportedly founded, highlighted his anti-academic stance and his belief in a more intuitive and individualistic approach to artistic creation. This philosophy resonated with the broader spirit of rebellion against established norms that characterized much of the avant-garde.

Grigoriev's influence extended through his teaching as well. Even after emigrating, he taught at various private art academies, passing on his knowledge and distinctive approach to a new generation of artists. His early mentor, Alexander Korovin, a prominent Russian Impressionist and stage designer, undoubtedly played a role in shaping Grigoriev's formative years, both as a friend and an artistic guide.

Later Years, Challenges, and Legacy

The later years of Grigoriev's life were marked by a mixture of continued artistic activity and increasing personal and financial challenges. He established a home in Cagnes-sur-Mer in the South of France, which he named "Borisella." This villa became his sanctuary and studio. While he continued to produce significant work and maintained a reputation, particularly in Europe, his reception in the United States during his visits in the 1920s and 1930s was somewhat mixed. The American public, while intrigued, did not always fully embrace his often stark and challenging vision.

Financial instability became a persistent issue in his later life. Despite his earlier successes and the high prices his portraits once commanded, the economic climate of the interwar period and the shifting tastes of the art market contributed to his difficulties. He reportedly faced periods of considerable hardship.

Boris Grigoriev passed away on February 7, 1939, in Cagnes-sur-Mer, France, on the cusp of the global conflict that would once again reshape the world. He died in relative poverty, a poignant end for an artist of such formidable talent and earlier acclaim.

Despite the vicissitudes of his later career, Boris Grigoriev's legacy endures. He is recognized as a key figure in Russian art of the early 20th century, an artist who masterfully blended Russian traditions with modernist innovations. His "Raseya" cycle remains a powerful and iconic depiction of the Russian peasantry and a profound meditation on national identity. His portraits are celebrated for their psychological acuity and stylistic verve.

His work is held in major museums and private collections worldwide, and he is studied as an important representative of the Russian avant-garde and the émigré art community. Grigoriev's art continues to speak to audiences with its emotional honesty, its technical brilliance, and its unflinching exploration of the human condition, particularly through the lens of the "Russian soul" that so deeply fascinated him throughout his life. He remains a testament to the enduring power of an artist who, despite personal and historical adversities, remained true to his unique and compelling vision.