Edgar Bundy (1862-1922) stands as a notable figure in British art during the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. Primarily recognized as a historical painter, Bundy possessed a remarkable talent for capturing moments of drama, intrigue, and daily life from bygone eras, particularly British history. Working proficiently in both oil and watercolour, his canvases are characterized by meticulous detail, vibrant colour palettes, and a strong narrative drive that appealed greatly to the tastes of his time. Though perhaps less revolutionary than some contemporaries, Bundy carved a distinct niche for himself through his skillful execution and evocative storytelling.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Brighton, Sussex, in 1862, Edgar Bundy's path to becoming a professional artist was somewhat unconventional for his era. Unlike many of his peers who underwent rigorous training in established art schools or the Royal Academy Schools, Bundy was largely self-taught. This lack of formal academic grounding did not seem to hinder his innate talent or ambition. His formative years remain relatively undocumented, but it is known that he spent some time gaining practical knowledge in the studio of Alfred Stevens.

It is crucial to distinguish this Alfred Stevens (1817-1875), the eminent English sculptor and designer celebrated for the Wellington Monument in St Paul's Cathedral, from the Belgian painter of the same name. While Bundy's time with Stevens might have been relatively brief, exposure to a working studio environment and perhaps Stevens's emphasis on draughtsmanship and composition likely provided valuable foundational insights. Bundy's ability to master complex figural arrangements and detailed settings suggests a dedicated period of self-directed study and practice, absorbing lessons from observation and the works of other artists.

The Artistic Landscape of Late Victorian Britain

To fully appreciate Edgar Bundy's career, one must consider the artistic climate in which he emerged. Late Victorian and Edwardian Britain saw a continued, though evolving, appreciation for narrative and historical painting. The Royal Academy of Arts remained the dominant institution, its annual Summer Exhibition a major event in the social and cultural calendar. Figures like Frederic Leighton and Edward Poynter, successive Presidents of the RA, upheld academic traditions often rooted in classical or historical themes, executed with polished technique.

Simultaneously, the influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, though its initial phase was long past, continued to resonate. The meticulous detail, jewel-like colours, and often moral or literary themes championed by artists like John Everett Millais (in his earlier work), William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti had left a lasting mark. Later artists associated with or influenced by the movement, such as Edward Burne-Jones and John William Waterhouse, explored medievalism, myth, and legend with romantic intensity. Bundy's work clearly absorbed aspects of this legacy, particularly the emphasis on detail and historical settings.

Historical genre painting, depicting specific events or anecdotal scenes from the past, was immensely popular. Artists like Lawrence Alma-Tadema achieved phenomenal success with meticulously researched reconstructions of classical antiquity, while others like William Quiller Orchardson explored moments of psychological tension in historical or contemporary settings. Andrew Carrick Gow and Edwin Austin Abbey were other contemporaries known for their depictions of British history. Bundy operated within this popular and competitive field, focusing primarily on British historical narratives.

Bundy's Developing Style

Edgar Bundy forged a style that blended academic finish with Pre-Raphaelite intensity of detail and colour. His commitment to historical accuracy, or at least verisimilitude, is evident in the careful rendering of costumes, architecture, and furnishings pertinent to the period depicted. This aligns with the principles advocated by John Ruskin, a major influence on the Pre-Raphaelites, who stressed "truth to nature" and close observation, although Bundy applied this more to historical artifacts than landscape.

His compositions are often complex, featuring multiple figures interacting within well-defined spaces. He possessed a strong sense of theatricality, arranging his figures to maximize narrative clarity and dramatic impact. Bundy was a capable draughtsman, defining forms clearly, and his use of colour was often bold and rich, contributing to the vividness of his scenes. He wasn't an innovator in the vein of James McNeill Whistler or the emerging Impressionist-influenced painters, but rather a master craftsman working within established traditions, refining them with his own narrative flair.

Themes and Subjects

Bundy's primary focus was history, particularly scenes drawn from British history of the medieval and Tudor/Stuart periods. He seemed less drawn to the classical world favoured by Alma-Tadema or Leighton, preferring instead the perceived romance, drama, and character of Britain's own past. His subjects often involved moments of conflict, conspiracy, social gathering, or quiet domesticity, allowing him to explore a range of human emotions and interactions within a historical context.

His paintings often tell a story, inviting the viewer to decipher the relationships and events unfolding on the canvas. Whether depicting soldiers preparing for battle, courtiers engaged in political intrigue, or families in period dress, Bundy aimed to transport the viewer back in time. This narrative quality, combined with the visual richness of the historical settings, made his work highly accessible and popular with audiences who enjoyed history presented in a visually engaging manner.

Mastering the Mediums: Oil and Watercolour

Bundy demonstrated considerable skill in both oil painting and watercolour. His oil paintings often possess a solidity and depth of colour suitable for large-scale historical compositions. He handled textures effectively, differentiating between fabrics, wood, metal, and stone, adding to the realism of his scenes. His use of light and shadow could be dramatic, highlighting key figures or creating a specific mood, whether the tension of a clandestine meeting or the warmth of a fireside gathering.

His proficiency in watercolour was also notable. During this period, watercolour painting in Britain had achieved a high degree of finish and status, moving far beyond its earlier use for sketches. Bundy was elected a member of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI), a testament to his skill in this medium. His watercolours often share the detailed execution and narrative focus of his oils, perhaps sometimes allowing for greater luminosity or atmospheric effects. This versatility allowed him to work across different scales and potentially reach different markets.

Key Works Explored

Several of Edgar Bundy's works stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns. The Morning of Sedgemoor (1905), held by the Tate Britain, depicts the aftermath of the Battle of Sedgemoor (1685), the final battle of the Monmouth Rebellion. Rather than the heat of battle, Bundy shows the weary, defeated rebels of the Duke of Monmouth's army resting in a rustic interior, capturing a moment of quiet despair and exhaustion. The attention to detail in the soldiers' attire and the humble setting is characteristic.

The Conspirators (exhibited 1911, held by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) is another powerful narrative piece. It portrays a dramatic interior scene, likely from the 17th century, where figures are gathered around a table. The atmosphere is thick with tension and suspicion, suggested by the characters' expressions and postures, and the play of light and shadow. The viewer is invited into a moment of unfolding drama, typical of Bundy's storytelling approach. The precise details of the room's furnishings and the figures' costumes anchor the scene historically.

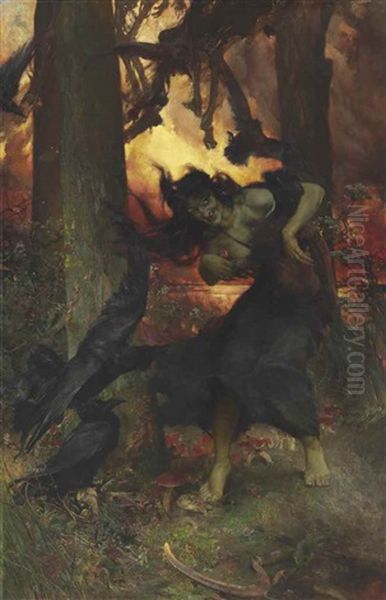

A Witch (1896) shows a different facet of Bundy's interest in the past, venturing into the realm of the supernatural and folklore. The painting depicts a wild-haired woman, presumably accused or practicing witchcraft, in a dark, atmospheric woodland setting. It evokes a sense of mystery and perhaps persecution, tapping into historical beliefs and fears surrounding witchcraft. This work demonstrates his ability to create mood and atmosphere alongside narrative detail.

Other works, like The Puritan and The Maid, further explore social interactions and character types within historical settings, often contrasting different social strata or viewpoints through carefully staged encounters. Across his oeuvre, Bundy consistently delivered detailed, colourful, and engaging historical vignettes.

Recognition and Career Milestones

Despite being self-taught, Edgar Bundy achieved significant professional recognition during his lifetime. He began exhibiting at the prestigious Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1881, showcasing his work regularly there for many years. This was the primary venue for artists seeking critical attention and patronage in Britain. His consistent presence indicates the acceptance of his work by the RA's selection committees.

His reputation extended beyond Britain. He exhibited at the Paris Salon, the French equivalent of the Royal Academy's exhibition, and notably won an award there in 1907. This international recognition further cemented his status. In addition to the RA and RI, Bundy was also a member of the Royal British Society of Artists (RBA), indicating his active participation in the London art world.

A significant milestone came in 1915 when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This honour, one step below full Academician status, recognized his standing within the British art establishment and his contributions to the field, particularly in historical painting. It was a mark of considerable achievement for an artist who had started without formal academic training.

Bundy and His Contemporaries

Placing Bundy alongside his contemporaries helps clarify his position. His detailed historical reconstructions invite comparison with Lawrence Alma-Tadema, but Bundy's focus on British history and often more overtly dramatic or anecdotal narratives differs from Alma-Tadema's polished visions of classical life. Compared to the high-minded classicism of Frederic Leighton or Edward Poynter, Bundy's work feels more grounded in specific historical moments and human interactions.

His narrative impulse connects him to painters like William Quiller Orchardson, known for his tense drawing-room dramas, though Orchardson's settings were often more contemporary or Regency. Bundy shared an interest in British history with painters like Andrew Carrick Gow and Edwin Austin Abbey, who also specialized in depicting historical events and figures with attention to period detail.

While influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, Bundy's work generally lacks the intense symbolism of Rossetti or the overt moralizing of Holman Hunt. His connection is more through the shared interest in historical subjects, meticulous rendering, and rich colour, perhaps closest in spirit to the later narrative works of Millais or aspects of John William Waterhouse's romantic historical scenes, although Waterhouse often leaned more towards myth and legend. Bundy remained firmly within the tradition of historical genre painting, skillfully executed but not pushing stylistic boundaries in the way that contemporaries like Walter Sickert or Philip Wilson Steer, influenced by French Impressionism, were beginning to do.

Collections and Legacy

Today, Edgar Bundy's works are held in several public collections, reflecting his historical significance and the quality of his output. Key institutions include Tate Britain in London (The Morning of Sedgemoor) and the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia. His painting The Conspirators found a home far from Britain at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington, indicating the reach of British art within the Commonwealth during his era. Works also appear periodically on the art market, sought after by collectors of Victorian and Edwardian painting.

Bundy's legacy is that of a highly competent and successful historical painter who catered effectively to the tastes of his time. He provided vivid, detailed, and often dramatic glimpses into Britain's past, satisfying a public appetite for history presented as engaging narrative. While perhaps overshadowed in art historical narratives by the rise of modernism, his work remains a valuable example of late Victorian and Edwardian academic and narrative painting. He stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of storytelling in art and the high level of technical skill achieved by artists working within that tradition.

Conclusion

Edgar Bundy navigated the British art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries with considerable success. As a largely self-taught artist, his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy and his recognition both at home and abroad speak volumes about his talent and dedication. Specializing in historical genre scenes, rendered with meticulous detail, strong colour, and a flair for narrative, Bundy captured moments of drama, intrigue, and everyday life from Britain's past. Though working within established conventions, he did so with a skill and conviction that earned him a respected place among his contemporaries and ensures his work continues to be appreciated for its craftsmanship and evocative power. He remains an important representative of a significant strand in British art history.