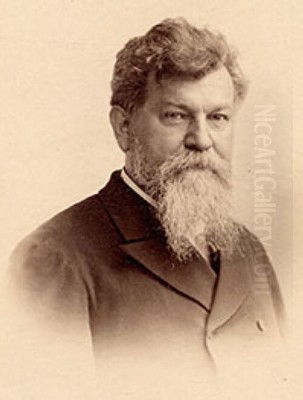

Edmund Kanoldt (1845-1904) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in nineteenth-century German art. A dedicated painter, draftsman, and illustrator, Kanoldt carved a niche for himself with his evocative landscapes and compelling mythological scenes. His work, deeply rooted in the traditions of German Romanticism and Neoclassicism, offers a window into the artistic currents of his time, while also hinting at the burgeoning changes that would sweep European art at the turn of the century. His legacy is further complicated and enriched by the notable artistic career of his son, Alexander Kanoldt, who would become a leading figure in the New Objectivity movement.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Weimar

Born in Großrudestedt, near the cultural heart of Weimar, in 1845, Edmund Kanoldt came of age in an environment steeped in artistic and literary heritage. Weimar, famously associated with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller, had long been a beacon of German Classicism. This classical spirit, emphasizing order, harmony, and idealized beauty, undoubtedly left an imprint on the young artist.

Kanoldt's formal artistic training began under the tutelage of Friedrich Preller the Elder (1804-1878) at the Weimar Saxon Grand Ducal Art School. Preller was himself a distinguished landscape painter, known for his "Odyssey Landscapes," a cycle of heroic scenes inspired by Homer's epic. Preller's influence on Kanoldt would be profound, instilling in him a love for the grand landscape, often imbued with historical or mythological significance. The master's emphasis on careful observation of nature, combined with an idealized, often Italianate, vision, provided a strong foundation for Kanoldt's developing style. The artistic atmosphere in Weimar, while perhaps past its zenith of Goethe's era, still fostered a respect for academic tradition and classical ideals, which Kanoldt absorbed.

The Italian Influence: Rome and the Ideal Landscape

Like many German artists of his generation, and indeed those who came before, such as the Nazarenes like Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius, Kanoldt was drawn to Italy. He spent a significant period in Rome, a city that had for centuries been a pilgrimage site for artists seeking to connect with classical antiquity and the High Renaissance. In Rome, Kanoldt would have encountered a vibrant community of international artists and been exposed to the sun-drenched landscapes and ancient ruins that had inspired painters for generations.

During his time in Rome, Kanoldt further honed his skills, likely working as a muralist for a period, and absorbed the lessons of the Italian masters. The Roman Campagna, with its picturesque ruins and expansive vistas, provided endless inspiration. This experience solidified his inclination towards idealized landscapes, often populated with figures from mythology or ancient history. Artists like Anselm Feuerbach (1829-1880), another German "Deutschrömer" known for his classically inspired figure paintings and melancholic mood, or Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901), whose mythological scenes often possessed a dreamlike, symbolic quality, were part of this broader tradition of Northern European artists finding profound inspiration in the Mediterranean world. Kanoldt's work from this period and later reflects this deep engagement with the classical past, seeking to evoke a sense of timeless beauty and narrative depth.

Karlsruhe: A Professor and Established Master

After his formative years of study and travel, which also included time in Munich, another major German art center, Edmund Kanoldt eventually settled in Karlsruhe. Here, he became a professor at the Grand Ducal Baden Art School, a position that recognized his skill and standing within the German art world. Karlsruhe, under the patronage of the Grand Dukes of Baden, had developed into a significant artistic hub, and its art school was well-respected.

In Karlsruhe, Kanoldt continued to develop his signature style. His landscapes were characterized by meticulous attention to detail, a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and a profound sense of place. While often idealized, they were grounded in a careful observation of nature, reflecting a typically German respect for the natural world. He was a contemporary of artists like Hans Thoma (1839-1924), who was also active in Karlsruhe and shared an interest in German landscape and folklore, albeit often with a more rustic, less overtly classical sensibility. Kanoldt's paintings often featured sweeping vistas, dramatic rock formations, and serene bodies of water, creating a mood that could be both heroic and deeply poetic. His works aimed to capture not just the physical appearance of a scene, but also its underlying spirit or emotional resonance, a characteristic that links him to the broader Romantic tradition.

Major Themes and Representative Works

Edmund Kanoldt's oeuvre primarily revolved around two interconnected themes: landscape and mythology. His landscapes were rarely mere topographical records; instead, they served as stages for human emotion or historical and mythological narratives. He was particularly drawn to scenes that evoked a sense of grandeur, solitude, or the sublime power of nature. This aligns him with earlier Romantic landscape painters such as Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), though Kanoldt's style was generally less overtly symbolic and more grounded in a classical sense of composition.

One of his notable works, often cited as representative, is Sappho Am Vorgebirge Leukate (Sappho on the Leucadian Cliff). This painting depicts the ancient Greek poetess Sappho, a figure of tragic love, contemplating her fate on the cliffs from which she was said to have leaped to her death. The work combines a dramatic coastal landscape with a poignant human story, showcasing Kanoldt's ability to fuse natural scenery with mythological pathos. The rendering of the landscape, with its rugged cliffs and expansive sea, would have been meticulously executed, creating a powerful backdrop for the solitary, contemplative figure of Sappho.

His illustrations and drawings also formed an important part of his output. As an illustrator, he would have applied his skills in composition and narrative to bring literary texts to life, a common practice for many academically trained artists of the period. Throughout his career, Kanoldt remained committed to a high degree of craftsmanship, emphasizing careful drawing, balanced composition, and a harmonious use of color. His art often carried religious or spiritual undertones, not necessarily in an overtly dogmatic way, but rather through a sense of reverence for nature and the enduring power of myth and history.

The Artistic Legacy: His Son, Alexander Kanoldt

The story of Edmund Kanoldt's artistic impact extends significantly through his son, Alexander Kanoldt (1881-1939). While Edmund remained firmly rooted in the 19th-century traditions of Romanticism and Neoclassicism, Alexander became a prominent figure in 20th-century German modernism, particularly associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement.

Alexander initially trained with his father, absorbing the foundational skills of drawing and painting. However, his artistic journey took him in a different direction. He studied at the Karlsruhe Academy and later in Munich, which at the turn of the century and in the early 1900s was a hotbed of avant-garde activity. In Munich, Alexander Kanoldt fell in with a circle of progressive artists. He became a co-founder of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKV, New Artists' Association of Munich) in 1909, alongside artists like Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), Alexej von Jawlensky (1864-1941), Gabriele Münter (1877-1962), and Marianne von Werefkin (1860-1938). This group was a precursor to Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), which Kandinsky, Franz Marc (1880-1916), and August Macke (1887-1914) would later form after ideological splits within the NKV.

Alexander Kanoldt's early involvement with the NKV shows his initial engagement with Expressionist tendencies and a move away from his father's more traditional style. For a time, his work showed influences of Post-Impressionism, particularly the structured brushwork and vibrant color of artists like Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), as seen in works like Alexander's Sunset (1906/07). He also explored Divisionist techniques. However, Alexander eventually grew dissatisfied with the increasing abstraction championed by Kandinsky and others, leading to his departure from these circles.

Alexander Kanoldt and the Rise of New Objectivity

After World War I, a conflict that profoundly impacted European society and art, Alexander Kanoldt emerged as one of the leading proponents of Neue Sachlichkeit. This movement, which gained prominence in Germany during the Weimar Republic, represented a turn away from the emotionalism and abstraction of Expressionism towards a more sober, realistic, and often sharply detailed depiction of the world. Other key figures of New Objectivity included George Grosz (1893-1959), Otto Dix (1891-1969), and Christian Schad (1894-1982), though the movement encompassed a range of styles from the veristic and bitingly satirical to the more classical and detached.

Alexander Kanoldt's version of New Objectivity leaned towards the latter, often described as a form of Magic Realism. His paintings, particularly his still lifes and architectural scenes, are characterized by a cool precision, smooth surfaces, and an almost unnerving clarity. Works like his Still Life (1925) or Kapelle in Südtirol (Chapel in South Tyrol, 1920) exemplify this style. Objects are rendered with meticulous detail, but they often possess a strange, frozen quality, imbued with a sense of stillness and timelessness that can feel unsettling or "magical." His architectural paintings, such as Die Stadt der tollen Türme (The City of Mad Towers, 1919), showcase a fascination with geometric forms and an almost de-personalized, objective view of the urban landscape.

In this, Alexander's work, while stylistically very different from his father's, perhaps shared a certain underlying classicism and a desire for order and structure, albeit expressed in a distinctly 20th-century idiom. His art was also influenced by Italian painters like Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) and Carlo Carrà (1881-1966) of the Pittura Metafisica movement, whose enigmatic, dreamlike cityscapes and still lifes prefigured some aspects of Magic Realism and Surrealism. Alexander's commitment to representational art, even within a modernist framework, and his rejection of pure abstraction, could be seen as a distant echo of the principles valued by his father's generation, albeit filtered through the lens of a radically changed world. He also had contact with artists like André Derain (1880-1954), whose own career saw a return to a more classical, ordered style after his Fauvist period, and was aware of Cubist explorations of form, even if he did not fully embrace Cubism himself.

Edmund Kanoldt in Art Historical Context

Edmund Kanoldt's career unfolded during a period of transition in German art. He was a product of the academic system that still held sway in the mid-to-late 19th century, a system that valued historical subjects, idealized landscapes, and technical proficiency. His art aligns with the later phases of German Romanticism and the enduring appeal of Neoclassicism, particularly among artists who sought inspiration in Italy. He can be seen in the company of other German painters who specialized in heroic or Italianate landscapes, such as Oswald Achenbach (1827-1905) of the Düsseldorf school, who was famed for his vibrant depictions of Italian life and scenery.

While Kanoldt may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists who were challenging artistic conventions elsewhere in Europe during his lifetime, his work represents a sincere and skilled engagement with the established artistic ideals of his era. He sought to create art that was beautiful, meaningful, and connected to the great traditions of European painting. His dedication to landscape painting, infused with mythological or historical resonance, contributed to a rich vein of German art that celebrated both the natural world and the cultural heritage of antiquity.

His role as an educator at the Karlsruhe Art School also meant that he directly influenced a younger generation of artists, passing on the skills and values he held dear. The fact that his own son, Alexander, while initially trained in this tradition, went on to become a key figure in a modernist movement like New Objectivity, highlights the dramatic shifts occurring in the art world across these two generations. It underscores how the solid, academic grounding provided by artists like Edmund Kanoldt could, paradoxically, serve as a foundation from which new, and very different, artistic expressions could emerge.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Beauty and Transition

Edmund Kanoldt's contribution to German art lies in his masterful execution of landscapes and mythological scenes that embody the spirit of late 19th-century German idealism. His paintings, characterized by their careful composition, detailed rendering, and poetic sensibility, offer a tranquil yet profound vision. He was an artist who valued tradition, craftsmanship, and the enduring power of nature and myth to inspire and elevate the human spirit.

While the art world would soon be revolutionized by movements that broke radically with these traditions, Kanoldt's work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of well-crafted, evocative painting. His legacy is twofold: firstly, in his own body of work, which merits appreciation for its lyrical beauty and technical skill; and secondly, through the artistic lineage that continued with his son Alexander, who, while forging a distinct path in the modernist landscape, carried forward a commitment to precision and a deep engagement with the visual world that, in some ways, connected back to the meticulous observation instilled by his father. Edmund Kanoldt thus stands as both a fine representative of his own era and a bridge to the complex artistic developments of the century that followed. His art invites us to appreciate a world where nature, myth, and history converged on the canvas to create scenes of enduring, if quiet, power.