Jacques-Augustin Pajou, a name synonymous with the refined elegance and intellectual rigor of French Neoclassicism, stands as one of the most significant sculptors of the 18th century. Born in Paris on September 27, 1730, and passing away in the same city on May 8, 1809, Pajou's life and career spanned a period of profound artistic and political transformation in France. From the waning days of the Rococo, through the intellectual ferment of the Enlightenment that fueled Neoclassicism, to the tumultuous years of the French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon, Pajou's art reflected and shaped the tastes of his time. His mastery of form, his sensitive portrayal of character, and his dedication to classical ideals earned him royal patronage, academic honors, and a lasting legacy in the annals of art history.

Early Life and Artistic Apprenticeship

Jacques-Augustin Pajou was fortunate to be born into an environment where artistry was valued. His father, Martin Pajou, was a sculptor and woodcarver of modest reputation, providing the young Jacques-Augustin with his earliest exposure to the craft. This familial background undoubtedly nurtured his nascent talent and inclination towards the plastic arts. Recognizing his son's potential, Martin Pajou ensured he received formal training.

At the tender age of fourteen, around 1744, Jacques-Augustin entered the prestigious workshop of Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne the Younger (1704-1778). Lemoyne was a dominant figure in French sculpture at the time, known for his lively portrait busts and his ability to bridge the Rococo's grace with an emerging classical sensibility. Under Lemoyne's tutelage, Pajou would have learned the fundamentals of modeling, carving, and the established academic traditions. Lemoyne's studio was a crucible for talent, and Pajou's skills rapidly developed, absorbing his master's technical proficiency while beginning to forge his own artistic identity. Other sculptors who were contemporaries or slightly senior to Pajou, and whose work would have formed part of the artistic milieu, included Edmé Bouchardon (1698-1762), known for his classical purity, and Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714-1785), another highly successful sculptor of the era.

The Prix de Rome and Italian Sojourn

A pivotal moment in any aspiring French artist's career during this period was winning the Prix de Rome. This prestigious award, granted by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), provided the recipient with a scholarship to study at the French Academy in Rome. Pajou achieved this distinction in 1748, at the age of eighteen, a testament to his exceptional talent. His winning sculpture, likely demonstrating a mastery of classical themes and forms, secured his passage to the heart of the classical world.

Pajou's stay in Rome, from 1752 to 1756, was transformative. Italy, and Rome in particular, was considered the ultimate finishing school for artists steeped in the classical tradition. Here, he was immersed in the masterpieces of antiquity – the sculptures of ancient Greece and Rome – as well as the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters like Michelangelo and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. He would have spent his days sketching ancient ruins, studying iconic sculptures in papal and private collections, and absorbing the principles of proportion, anatomy, and idealized beauty that defined classical art. This direct engagement with the sources of Neoclassicism profoundly shaped his artistic vision, instilling in him a deep reverence for clarity, harmony, and noble simplicity. The director of the French Academy in Rome during part of his stay was the painter Charles-Joseph Natoire, and Pajou would have interacted with other pensionnaires, further enriching his experience.

Ascent in the Parisian Art World

Upon his return to Paris in 1756, Pajou was well-equipped to make his mark. His Roman studies had refined his technique and solidified his commitment to Neoclassical ideals, which were increasingly gaining favor over the more exuberant Rococo style. He quickly sought recognition from the Académie Royale, the gateway to prestigious commissions and official standing.

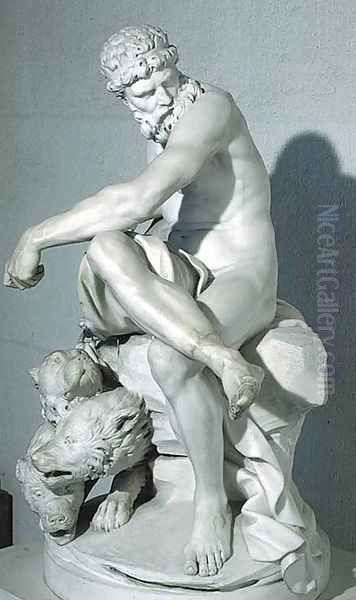

In 1759, Pajou was "agréé" (approved) by the Academy, and in 1760, he was received as a full member ("reçu") upon presentation of his stunning reception piece, Pluton, Cerbère enchaîné (Pluto Holding Cerberus in Chains). This powerful marble group, now in the Louvre Museum, showcased his technical virtuosity, his understanding of dynamic composition, and his ability to imbue classical mythology with dramatic force. The choice of subject, depicting the god of the underworld with his three-headed hound, was both ambitious and indicative of his classical leanings. Its successful reception cemented his reputation as a sculptor of significant talent.

![Psyche abandonnee [detail #1] (Psyche Abandoned) by Jacques-Augustin Pajou](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/245358/m/jacquesaugustin-pajou-psyche-abandonnee-detail-1-psyche-abandoned-735e3a62.jpg)

Following his admission to the Academy, Pajou's career flourished. He was appointed a professor at the Academy in 1762, a role that allowed him to influence the next generation of artists. He became a regular exhibitor at the biennial Salons, the premier public art exhibitions in Paris, where his works were seen by critics, collectors, and the public. His skill in various genres – mythological subjects, allegorical figures, religious works, and especially portraiture – brought him numerous commissions.

Royal Patronage and Major Commissions

Pajou's talent did not go unnoticed by the French court and aristocracy. He became a favored sculptor of King Louis XV and later, King Louis XVI. This royal patronage led to a series of important commissions for public buildings and royal residences. He contributed significantly to the sculptural decoration of the Opéra Royal at the Palace of Versailles, a project overseen by the architect Ange-Jacques Gabriel. His work here, executed in the 1760s, included allegorical figures and decorative reliefs that harmonized with the opulent yet classically informed architecture.

He also created decorative sculptures for the Palais Royal in Paris and the Palais de Justice. His ability to work on a grand scale and to integrate sculpture seamlessly with architecture made him a sought-after collaborator. One notable collaboration was with the architect Charles De Wailly, with whom he worked on projects for the Marquis de Voyer. Though their relationship experienced a dispute over payments in 1772, their professional association continued, highlighting the complex dynamics of artistic partnerships.

Pajou's oeuvre included numerous portrait busts of eminent figures, a genre in which he excelled. He captured not only the likeness but also the character and intellectual presence of his sitters. Among his most celebrated portraits are those of the naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, the philosopher René Descartes, the theologian Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (often cited as "Bossu" in some records, but clearly referring to the famous bishop), and Queen Marie Leszczynska, the wife of Louis XV. His bust of Madame du Barry, Louis XV's mistress, is a particularly fine example of his ability to combine elegance with a sense of personality, executed with a delicate Rococo charm that still hints at underlying classical structure. These portraits were highly prized for their lifelike quality and psychological insight, rivaling those of his contemporary, Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828), who is perhaps the most famous Neoclassical portrait sculptor.

Masterpieces and Artistic Style

Pajou's artistic style is firmly rooted in Neoclassicism, characterized by its emphasis on clarity of form, idealized beauty, and inspiration from classical antiquity. However, his work often retained a certain French grace and sensitivity, preventing it from becoming overly cold or academic. He masterfully balanced intellectual rigor with an appreciation for the sensuous qualities of the human form and the materials he worked with.

One of his most iconic works is Psyché abandonnée (Psyche Abandoned), completed in 1790 and now in the Louvre. This marble statue depicts the mythological princess Psyche in a moment of despair after being abandoned by her lover, Cupid. The figure's pose, with its graceful contrapposto and expressive gesture, conveys a profound sense of sorrow and vulnerability. The smooth, polished surface of the marble enhances the sculpture's sensuous appeal, while the idealized features and classical drapery adhere to Neoclassical principles. The work was highly acclaimed at the Salon of 1791 and remains one of his most beloved creations. It demonstrates his ability to convey deep emotion within a framework of classical restraint, a hallmark of the best Neoclassical art.

Another significant work is Mercure (Mercury), often realized in both terracotta and marble. This subject, the swift messenger god, allowed Pajou to explore dynamic movement and elegant anatomy. His representations of Mercury typically show the god in a poised, athletic stance, embodying youthful energy and divine grace. These works, like his Pluto, demonstrate his profound understanding of human anatomy, likely honed through academic study and observation.

Pajou was versatile in his choice of materials, working adeptly in terracotta, marble, and bronze. His terracotta models, often preparatory studies for larger marble works, possess a remarkable freshness and immediacy, capturing his initial creative impulse. His marble carving was exceptionally refined, achieving a high degree of polish and subtlety in the rendering of flesh, hair, and drapery.

His contributions to architectural decoration were also significant. Beyond the Opéra Royal at Versailles, he created allegorical figures representing the sciences and arts, as well as reliefs for public monuments. These works required an ability to adapt his style to the specific architectural context and to convey meaning through symbolic representation. His involvement in projects like the decoration of the Montpellier Cathedral further underscores his versatility.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Pajou operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment. Paris was the undisputed center of the European art world in the 18th century, and the Académie Royale was a powerful institution that shaped artistic taste and careers. Besides his teacher Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne and his great contemporary Jean-Antoine Houdon, other notable sculptors of the period included Étienne Maurice Falconet (1716-1791), known for his graceful figures and his work for Catherine the Great of Russia; Clodion (Claude Michel, 1738-1814), celebrated for his charming Rococo-style terracotta groups; and Augustin Dumont (1701-1784). These artists, along with others like Guillaume Coustou the Younger (1716-1777) and Félix Lecomte (1737-1817), contributed to the rich tapestry of French sculpture.

In the broader art world, the shift towards Neoclassicism was also being championed by painters. Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) emerged as the leading figure of Neoclassical painting, with works like The Oath of the Horatii (1784) becoming manifestos of the new style. Other painters like Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805) focused on moralizing genre scenes, while Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842) and Adelaide Labille-Guiard (1749-1803) excelled in portraiture, often with a Neoclassical clarity. The landscape painter Hubert Robert (1733-1808), famous for his picturesque ruins, also reflected the era's fascination with antiquity. While Pajou was a sculptor, the prevailing artistic currents and intellectual debates of the Enlightenment, which emphasized reason, order, and civic virtue, influenced all art forms. The Academy, while fostering talent, was also a place of artistic rivalries and shifting tastes. Some accounts suggest that at times, the Academy might have favored artists like Guillaume Guillon-Lethière (1760-1832), a painter, or others whose style more rigidly adhered to certain academic expectations, though Pajou's consistent success indicates his high standing.

The French Revolution and Its Impact

The French Revolution, which began in 1789, brought profound upheaval to French society and had a significant impact on artists like Pajou who had thrived under royal patronage. The old systems of support were dismantled, and many artists found their careers and even their lives at risk. As a prominent member of the Royal Academy (which was suppressed in 1793) and a recipient of royal favor, Pajou was in a precarious position during the Reign of Terror (1793-1794).

In 1793, to escape the dangers and turmoil in Paris, Pajou fled to Montpellier in southern France. He remained there for about three years, living in relative poverty and facing considerable hardship. The revolutionary government also initiated a campaign to destroy symbols of the monarchy and the aristocracy, which sometimes included artworks. Pajou was appointed to a commission responsible for preserving artworks in the Hérault department, a role that, while perhaps offering some protection, also placed him in a difficult position of navigating the Revolution's destructive and preservative impulses. This period was undoubtedly challenging, both personally and professionally, as the demand for luxury goods and traditional forms of art declined.

Later Years, Napoleonic Recognition, and Legacy

Pajou returned to Paris around 1796, his health somewhat impaired by the difficulties he had endured. The art world he returned to was different, with new patrons and evolving tastes under the Directory and later, the Napoleonic regime. Despite the challenges, he continued to work.

Under Napoleon Bonaparte, there was a renewed emphasis on art that glorified France and its leader, often drawing on classical Roman imperial models. Pajou received some recognition during this period. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, a prestigious order established by Napoleon. He was also appointed curator of antiquities at the Musée Napoléon (now the Louvre), a role that acknowledged his deep knowledge of classical art. He held various positions within the reconfigured art institutions, including serving as Rector of the Academy in 1792, just before its suppression, and later being involved with the Institut de France, which replaced the old royal academies.

His son, Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou (1766-1828), also became an artist, primarily a painter. This continuation of the artistic lineage within the family is a noteworthy aspect of their story. The younger Pajou, sometimes referred to as Pajou fils, achieved success as a portraitist and painter of historical and genre scenes.

Jacques-Augustin Pajou died in Paris on May 8, 1809, at the age of 78. He left behind a substantial body of work that exemplifies the elegance, intellectual depth, and technical brilliance of French Neoclassical sculpture. His sculptures are found in major museums worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Pajou's legacy lies in his contribution to the Neoclassical movement, his masterful portraiture, and his significant decorative works. He successfully navigated the transition from the late Rococo to the full flowering of Neoclassicism, adapting his style while maintaining a high level of artistic integrity. His ability to imbue classical forms with warmth and psychological insight ensured his enduring appeal. He stands alongside Houdon as one of the preeminent French sculptors of the late 18th century, a testament to a career dedicated to the pursuit of beauty and excellence in the art of sculpture. His influence extended through his students and through the enduring presence of his works, which continue to be admired for their grace, power, and timeless quality. Artists like Joseph Chinard (1756-1813) and François Joseph Bosio (1768-1845) would continue the Neoclassical tradition into the 19th century, building on the foundations laid by masters like Pajou.