Max-Alfred Buri (1868-1915) stands as a significant figure in Swiss art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter deeply rooted in his native soil, Buri dedicated his artistic endeavors to capturing the essence of Swiss rural life, particularly the stoic dignity of its peasantry. His work, characterized by its robust realism and often monumental scale, offers a profound insight into the cultural and social fabric of Switzerland during a period of evolving national identity. This exploration will delve into his background, artistic style, key works, and his position within the broader context of European art, highlighting his connections and distinctions with contemporary artists.

Nationality and Professional Foundations

Max-Alfred Buri was unequivocally Swiss, born on July 10, 1868, in Burgdorf, a town in the canton of Bern. His Swiss nationality was not merely a biographical detail but a profound influence on his thematic choices and artistic identity. He hailed from a region known for its strong agricultural traditions and distinctive cultural heritage, elements that would become central to his oeuvre. His professional journey as a painter was shaped by a series of academic experiences and personal artistic explorations that solidified his commitment to a particular kind of figurative art.

Buri's formal artistic training began in Switzerland, likely in Basel, before he sought further instruction abroad, a common path for aspiring artists of his generation. He spent time in Munich, a major art center in the German-speaking world, where he would have been exposed to the prevailing trends of Naturalism and the legacy of the Munich School, known for its dark palette and detailed realism. Following his studies in Munich, Buri, like many of his contemporaries, was drawn to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world in the late 19th century.

In Paris, from 1889 to 1893, he enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school that offered a more liberal alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian attracted students from across the globe and was a crucible for various artistic ideas. Here, Buri would have encountered a diverse range of influences, from lingering academic traditions to the burgeoning movements of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism. Despite these varied exposures, Buri's artistic compass remained firmly set towards a form of realism that emphasized strong draftsmanship and a direct engagement with his subject matter. His time in these artistic hubs provided him with technical skills and a broader understanding of contemporary art, yet it ultimately reinforced his inclination towards themes grounded in his Swiss heritage.

Artistic Style and Affiliations: Realism with a Monumental Touch

Max-Alfred Buri's artistic style is most accurately characterized as a powerful form of Realism, often infused with a monumental quality that elevates his subjects beyond mere genre depiction. While he was active during a period when Impressionism had already made its mark and Post-Impressionist movements like Symbolism and Art Nouveau were gaining traction, Buri largely remained committed to a figurative tradition that emphasized solidity, tangible presence, and a deep connection to the earth.

His primary affiliation can be seen with the broader European Realist movement, which had its roots in artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet in France. Buri shared their interest in depicting the lives of ordinary people, particularly peasants, with honesty and without idealization. However, Buri’s interpretation of Realism was distinctly Swiss and bore the imprint of his own artistic temperament. He was particularly drawn to the figures of the Bernese Oberland, portraying them with a rugged strength and an almost sculptural quality.

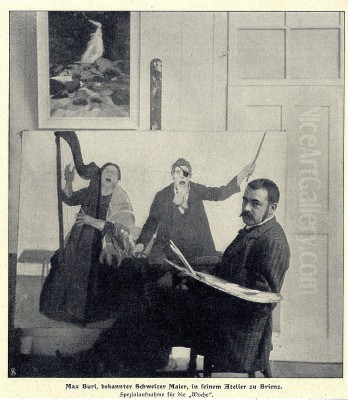

A significant influence on Buri, and a point of comparison, is the work of his compatriot Ferdinand Hodler. While Hodler moved more explicitly into Symbolism and developed his theory of "Parallelism," there are shared sensibilities, particularly in the monumental treatment of figures and a certain gravitas. Buri, however, tended to be more grounded in the specific and less overtly symbolic than Hodler in his mature phase. He can be considered part of what is sometimes referred to as the "School of Brienz," a loose designation for artists who, like Buri, settled in or frequently depicted the region around Lake Brienz, focusing on its landscapes and inhabitants. This local focus also connects him to the "Heimatstil" (Homeland Style), an artistic and architectural movement in German-speaking countries that emphasized regional traditions and character.

Buri's paintings are notable for their strong, often somber, color palettes, their emphasis on form and volume, and their direct, unembellished portrayal of his subjects. He avoided the fleeting light effects of Impressionism, preferring instead a more stable and enduring representation. His figures often possess a stoic, introspective quality, reflecting the harsh realities and quiet dignity of rural labor. While not strictly a Symbolist, there is an underlying sense in his work of capturing something essential and timeless about the human condition as experienced through the lives of Swiss peasants.

Representative Works and Important Exhibition Records

Max-Alfred Buri's oeuvre is distinguished by several powerful paintings that encapsulate his artistic vision and thematic concerns. Among his most representative works are those that depict the farmers and villagers of the Bernese Oberland, rendered with his characteristic monumentality and psychological depth.

One of his most iconic paintings is "Die Dorfpolitiker" (The Village Politicians), created around 1904. This work shows a group of men, presumably local figures of some standing, engaged in earnest discussion, perhaps in a tavern or village meeting place. The figures are robust, their faces etched with character and experience. Buri captures a sense of serious deliberation, reflecting the democratic traditions of Swiss rural communities. The composition is solid, the figures closely grouped, emphasizing their shared purpose and the weight of their conversation.

Another significant work is "Holzer (The Woodcutter)" or similar depictions of solitary male figures engaged in labor. These paintings often highlight the physical strength and resilience of the worker, set against a backdrop that, while present, serves primarily to contextualize the human subject. Buri’s woodcutters and farmers are not romanticized heroes but individuals deeply connected to their environment and their toil.

"Frau beim Heuen" (Woman Raking Hay) is an example of his portrayal of women in rural settings. Again, the emphasis is on the dignity of labor and the strength of the individual. These figures are often depicted with a quiet intensity, their forms solid and grounded. His portraits, such as those of local personalities or family members, also demonstrate his skill in capturing individual character with an unflinching gaze.

Regarding exhibition records, Buri was an active participant in the Swiss art scene and also exhibited internationally. He regularly showed his work at the Swiss National Art Exhibitions (Turnus-Ausstellungen), which were crucial platforms for Swiss artists. His powerful depictions of national types resonated with a growing sense of Swiss identity. Furthermore, Buri exhibited in major European art centers. He participated in exhibitions at the Munich Glaspalast and was associated with the Munich Secession, a progressive group of artists who broke away from the established academic art institutions. His work was also shown in Paris, likely at the Salons, which, despite the rise of independent exhibitions, remained important venues for gaining international recognition.

His participation in these exhibitions, particularly those of the Secession movements (like Munich and later Vienna, though his direct involvement with Vienna is less clear), indicates an alignment with artists seeking new forms of expression, even if his own style remained rooted in a powerful realism rather than embracing the more decorative or avant-garde tendencies of some of his contemporaries. His works were acquired by major Swiss museums, including the Kunstmuseum Bern and the Kunsthaus Zürich, cementing his place in the canon of Swiss art.

Anecdotes and the Character of the Artist

While detailed personal anecdotes about Max-Alfred Buri are not as widely circulated as those of some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, the available information paints a picture of an artist deeply committed to his work and his chosen environment. He established his home and studio in Brienz, a picturesque town on the shores of Lake Brienz in the Bernese Oberland. This decision was not merely for aesthetic reasons; it was a conscious immersion in the world he sought to depict.

Buri was known to be a man of strong character, perhaps somewhat reserved, but with a profound connection to the local people he painted. He didn't just observe them from a distance; he lived among them, understood their dialect, their customs, and the rhythms of their lives. This intimate knowledge is palpable in his portraits and genre scenes, which possess an authenticity that could only come from deep familiarity. It is said that he would often find his models among the local population, convincing them to sit for him, and his depictions were valued for their truthfulness, even if they were not always conventionally flattering.

There's a sense that Buri saw himself as a chronicler of a way of life that was, even then, beginning to face the pressures of modernization. His monumental figures can be interpreted as an attempt to give permanence and dignity to these individuals and their traditions. He was reportedly a meticulous worker, spending considerable time on each canvas to achieve the desired solidity and psychological depth.

One interesting aspect of his life was his relationship with Ferdinand Hodler. While Hodler became an international figure, Buri remained more focused on his Swiss subjects. They were contemporaries and both key figures in Swiss art, and while their paths diverged stylistically, there was likely a degree of mutual respect and perhaps even artistic dialogue, particularly in their shared interest in creating a distinctly Swiss form of monumental art. Buri's decision to live and work in Brienz, somewhat removed from the main art centers after his studies, suggests an artist who found his primary inspiration and purpose in a specific locale, rather than in the shifting trends of the international art scene. His premature death in 1915, at the age of 47, in Interlaken, cut short a career that was still very much in its prime, leaving a legacy of powerful, enduring images of Swiss life.

Contemporaries in the Artistic Landscape

Max-Alfred Buri was active during a vibrant and transformative period in European art, spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries. To understand his position, it's essential to consider the diverse array of artists working alongside him, both within Switzerland and across the continent.

Within Switzerland itself, the towering figure was Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918). Hodler's evolution from Realism to Symbolism and his development of "Parallelism" made him a leading force in Swiss modernism. Other notable Swiss contemporaries included Cuno Amiet (1868-1961), who, unlike Buri, embraced color and Post-Impressionist tendencies, becoming a pioneer of modern Swiss painting with a brighter palette. Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933), father of Alberto Giacometti, was another key figure, known for his Post-Impressionist landscapes and vibrant use of color, influenced by artists like Giovanni Segantini. Félix Vallotton (1865-1925), though largely active in Paris and associated with Les Nabis, retained his Swiss identity and produced incisive portraits, nudes, and genre scenes. Earlier, but whose influence on Swiss genre painting was still felt, was Albert Anker (1831-1910), known for his meticulous and charming depictions of Swiss rural life, though Buri’s approach was generally more rugged and less idealized.

Looking beyond Switzerland, in France, the legacy of Realism continued, but new movements were dominant. Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) and Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) were earlier figures whose impact on Realist painters like Buri was foundational. Contemporaneously, artists like Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) and Claude Monet (1840-1926) were established masters of Impressionism. The Post-Impressionists, such as Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), had already made their revolutionary contributions. Symbolist painters like Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898) and Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) were also highly influential.

In the German-speaking world, artists like Max Liebermann (1847-1935) in Germany were leading figures of German Impressionism and later, a more sober Realism. The Munich Secession, with which Buri exhibited, included artists like Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) and Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), who explored various styles from Symbolism to a nascent Expressionism. In Austria, Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) was a dominant figure of the Vienna Secession, known for his opulent, decorative style. Further afield, artists like the Norwegian Edvard Munch (1863-1944) were pushing the boundaries of emotional expression. This rich tapestry of artistic activity provides the backdrop against which Buri carved out his distinctive niche.

Intersections and Influential Relationships

Among the many artists active during his time, several had notable intersections or influential relationships with Max-Alfred Buri, either directly or through shared artistic currents.

The most significant relationship within Swiss art was undoubtedly with Ferdinand Hodler. Both artists aimed to create a monumental art form rooted in Swiss identity, and both frequently depicted strong, archetypal figures. While Hodler's path led him to a more stylized and overtly symbolic language, particularly with his theory of "Parallelism" (rhythmic arrangements of figures and forms), Buri remained more grounded in a direct, earthy Realism. However, Hodler's emphasis on the human figure as a carrier of profound meaning and his powerful draftsmanship likely resonated with Buri. They were contemporaries who exhibited in similar circles, and the dialogue, whether explicit or implicit, between their approaches to national themes is a key aspect of Swiss art history of the period. Buri's work can be seen as a more naturalistic counterpoint to Hodler's symbolic grandeur.

The influence of earlier French Realists like Jean-François Millet and Gustave Courbet is fundamental to Buri's work. Millet's dignified portrayals of peasant labor, such as "The Gleaners" or "The Sower," set a precedent for taking rural life as a serious subject for art. Courbet’s robust materialism and his commitment to painting "real allegories" of contemporary life also provided a powerful model. Buri absorbed these influences, adapting them to the specific context of the Swiss Alps and its people.

His time in Munich would have exposed him to the German Naturalist movement and artists associated with the Munich School, such as Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900). Leibl and his circle were known for their unvarnished depictions of peasant life, characterized by meticulous detail and psychological insight. This tradition of German Realism, with its often somber palette and focus on character, would have found fertile ground in Buri's artistic inclinations.

While Buri did not embrace Impressionism, the movement's existence and its challenge to academic norms formed part of the artistic climate. His adherence to a more solid, form-based realism can be seen as a conscious choice in this context. Similarly, while he wasn't a Symbolist in the vein of Puvis de Chavannes or Arnold Böcklin (another Swiss artist, though largely active abroad, whose mythological and symbolic landscapes were influential), the general turn-of-the-century interest in conveying deeper meanings and moods beyond surface appearances might have subtly informed the gravitas and psychological intensity of Buri's figures.

Compared to his Swiss contemporary Cuno Amiet, Buri's path was quite different. Amiet, after early studies with Hodler, embraced the color and light of French Post-Impressionism, particularly the influence of Pont-Aven school artists like Gauguin, and became a leading figure of Swiss modernism known as "Der farbige Amiet" (The colorful Amiet). Buri, by contrast, remained committed to a more traditional, form-based approach, emphasizing volume and a more subdued, earthy palette. This highlights the diversity within Swiss art at the time.

Another contemporary, Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899), though Italian by birth, spent much of his later career in the Swiss Alps and is often considered in the context of Swiss art. Segantini's Divisionist technique and his symbolic depictions of Alpine life and pantheistic themes offered another distinct approach to mountain landscapes and their inhabitants, contrasting with Buri's more direct realism.

Buri's work, therefore, exists at a crossroads: deeply indebted to 19th-century Realism, contemporary with the rise of various modernisms, and specifically engaged with the project of defining a Swiss national art alongside figures like Hodler, yet carving out his own unique path through his powerful and empathetic portrayal of the Bernese peasantry. His legacy is that of an artist who, with unwavering focus, gave monumental expression to the people and the spirit of his homeland.