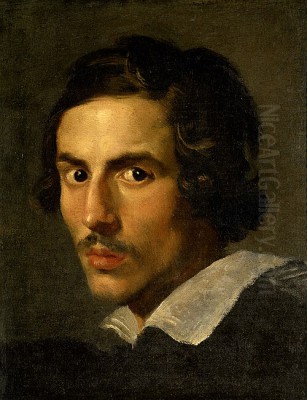

Gian Lorenzo Bernini stands as a colossus in the history of art, arguably the most influential sculptor and architect of the Baroque era. His prodigious talent, boundless energy, and long career allowed him to dominate the artistic landscape of 17th-century Rome, leaving an indelible mark on the city and shaping the very definition of Baroque style. A sculptor, architect, painter, playwright, and stage designer, Bernini embodied the ideal of the universal artist, creating works that continue to awe and inspire with their dramatic intensity, technical brilliance, and profound emotional depth.

Early Life and Prodigious Beginnings

Gian Lorenzo Bernini was born in Naples on December 7, 1598. His father, Pietro Bernini, was himself a talented Mannerist sculptor from Florence, providing Gian Lorenzo with his earliest training. The family moved to Rome around 1605-1606, drawn by the opportunities offered by the papacy and the city's burgeoning artistic scene. Pietro worked on several papal projects, and young Gian Lorenzo quickly absorbed the atmosphere of artistic creation and ambition.

Even as a child, Bernini's talent was extraordinary. Anecdotes abound regarding his precocious skill. It is said that by the age of eight, he had already carved a remarkable stone head that impressed established artists. His father, recognizing his son's exceptional gift, facilitated his exposure to the great art collections of Rome, particularly the Vatican's collection of antique sculptures and the masterpieces of the High Renaissance, including the works of Michelangelo.

One influential early encounter was with the painter Annibale Carracci, a key figure in the transition towards the Baroque. More significantly, the young Bernini caught the attention of Cardinal Maffeo Barberini (the future Pope Urban VIII) and, crucially, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of Pope Paul V. Pope Paul V himself is famously said to have seen the boy's work and declared him the "Michelangelo of his century," urging Cardinal Barberini to nurture his talent carefully.

The Patronage of Scipione Borghese: Sculptural Breakthroughs

![Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius [detail: 1] by Gian Lorenzo Bernini](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/113244/m/gian-lorenzo-bernini-aeneas-anchises-and-ascanius-detail-1-d8ea2a32.jpg)

Cardinal Scipione Borghese became Bernini's most important early patron. A passionate collector with a keen eye for talent, Borghese commissioned a series of large-scale sculptural groups for his villa (now the Galleria Borghese). These works, executed primarily between 1618 and 1625, established the young Bernini, still in his early twenties, as a sculptor of unparalleled virtuosity and originality.

The first of these was Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius (c. 1618-19), depicting the Trojan hero fleeing the burning city with his father and son. While showing the influence of his father Pietro and Mannerist principles in its somewhat spiral composition, it already hinted at Gian Lorenzo's burgeoning dynamism.

This was followed by the breathtaking Pluto and Proserpina (1621-22), capturing the violent abduction of Proserpina by the god of the underworld. Here, Bernini achieved an astonishing realism in marble, depicting the god's fingers pressing into Proserpina's flesh and her tears of desperation, creating a powerful sense of movement and intense emotion within the hard stone.

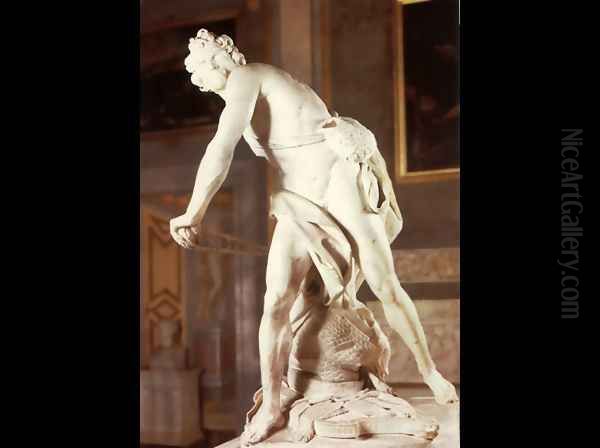

The David (1623-24) marked a radical departure from previous interpretations by Renaissance masters like Donatello and Michelangelo. Bernini chose not a moment of contemplation before or after the battle, but the climax of the action itself. David is caught mid-motion, twisting his body, biting his lip in concentration, ready to unleash the stone from his sling. The sculpture demands space, engaging the viewer from multiple angles and conveying an unprecedented level of physical tension and psychological focus. It is said Bernini used his own face, reflected in a mirror held by Maffeo Barberini, as the model for David's intense expression.

Perhaps the most celebrated of the Borghese group is Apollo and Daphne (1622-25). Based on Ovid's Metamorphoses, it depicts the nymph Daphne transforming into a laurel tree at the very moment Apollo reaches her. Bernini masterfully captures the metamorphosis in progress: Daphne's fingers sprout leaves, her toes take root, and bark encases her smooth skin, all while conveying her cry of anguish and Apollo's stunned realization. The technical skill in rendering textures – leaves, bark, hair, flesh – is astounding, matched only by the work's poetic narrative power and fluid movement. These Borghese sculptures cemented Bernini's reputation and showcased the key elements of his developing style: dynamic movement, intense emotion, narrative drama, and startling realism.

Under the Wing of Urban VIII: Dominance at St. Peter's

The election of Cardinal Maffeo Barberini as Pope Urban VIII in 1623 marked a turning point in Bernini's career. Urban VIII was an ambitious patron of the arts, determined to use art and architecture to glorify the papacy and the Catholic Church in the era of the Counter-Reformation. He saw Bernini as the ideal artist to realize his vision, showering him with commissions and effectively making him the artistic director of Rome.

Bernini's most significant work under Urban VIII centered on St. Peter's Basilica. His first major project there was the monumental Baldacchino (1624-1633), a colossal bronze canopy placed over the high altar, which itself stands above the traditional site of St. Peter's tomb. Standing nearly 30 meters (almost 100 feet) tall, the Baldacchino is an extraordinary fusion of sculpture and architecture. Its giant, twisting Solomonic columns, inspired by those believed to have come from the Temple of Solomon, create a sense of upward movement and grandeur. Adorned with Barberini bees (the family symbol) and laurel leaves, topped with statues of angels and an orb and cross, it perfectly frames the focal point of the basilica and serves as a triumphant symbol of papal authority and the Catholic faith. The casting of such an enormous bronze structure was a feat of engineering in itself.

Bernini also contributed significantly to the decoration of the basilica's crossing piers, designing niches and overseeing the creation of colossal statues of saints associated with the basilica's primary relics, including St. Longinus (partially carved by Bernini himself). He was appointed Architect of St. Peter's in 1629, succeeding Carlo Maderno, further solidifying his control over the most important artistic project in Christendom.

During Urban VIII's reign, Bernini also created numerous portrait busts, including several of the Pope himself, capturing his likeness with remarkable immediacy and psychological insight. His bust of his early patron, Cardinal Scipione Borghese (two versions, 1632), is famed for its lifelike quality, capturing a fleeting moment and expression, making the marble seem almost alive.

Sculptural Mastery: Emotion, Movement, and Spirituality

Throughout his long career, Bernini continued to push the boundaries of sculpture, particularly in his handling of marble. He possessed an unparalleled ability to make stone convey the softness of flesh, the texture of fabric, the dynamism of movement, and the intensity of human emotion. His figures are rarely static; they twist, gesture, and interact with the space around them, drawing the viewer into the narrative and emotional core of the work.

![Apollo and Daphne [detail] by Gian Lorenzo Bernini](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/113207/m/gian-lorenzo-bernini-apollo-and-daphne-detail-355147c2.jpg)

His religious sculptures are particularly powerful examples of Baroque spirituality, often depicting moments of intense mystical experience. The most famous is the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-1652) in the Cornaro Chapel of Santa Maria della Vittoria. Bernini designed the entire chapel as a theatrical setting, complete with sculpted members of the Cornaro family watching from side boxes. The central group depicts Saint Teresa of Ávila swooning in spiritual rapture as an angel prepares to pierce her heart with a golden arrow, symbolizing divine love. Teresa's abandoned pose, her parted lips and closed eyes, convey an intense, almost physical ecstasy. Golden rays descend from a hidden window above, illuminating the white marble figures against the darker, colored marble background. The work masterfully blends spiritual fervor with a palpable sensuality, embodying the Baroque desire to make the divine tangible and emotionally overwhelming.

Another late masterpiece of religious sculpture is the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni (1671-1674) in the Altieri Chapel of San Francesco a Ripa. Similar to the Saint Teresa, it depicts the subject in a state of mystical communion, lying on a deeply crumpled mattress, her head thrown back in pious agony or ecstasy. Bernini again uses the surrounding architecture and controlled lighting to heighten the dramatic and emotional impact, demonstrating his concept of the bel composto, or the beautiful whole, where sculpture, architecture, and painting (or light effects) unite.

His portrait busts remained exceptional throughout his career. The bust of Costanza Bonarelli (c. 1636-37), the wife of one of his assistants with whom Bernini had a tumultuous affair, is striking for its informal intimacy and psychological penetration. His later bust of King Louis XIV of France (1665), created during a trip to Paris, conveys regal majesty through the dynamic turn of the head, the flowing hair, and the intricately carved lace and armor, setting a standard for royal portraiture.

Architectural Vision: Shaping Papal Rome

While primarily famed as a sculptor, Bernini was also a highly innovative and influential architect. His architectural work is characterized by a similar dynamism, grandeur, and integration of the arts found in his sculpture. He favored classical forms but manipulated them with a Baroque sensibility, using curves, colossal orders, and rich materials to create dramatic spatial experiences.

His most defining architectural achievement is the design of St. Peter's Square (Piazza San Pietro), constructed between 1656 and 1667 under Pope Alexander VII. Bernini conceived the vast space not as a self-contained entity but as an embracing entrance to the basilica. He created two distinct sections: a trapezoidal area leading from the church facade, which corrects perspective lines, and a huge oval area defined by two sweeping, free-standing colonnades. These colonnades, formed by four rows of massive Doric columns, are designed to feel like the "motherly arms of the Church," welcoming pilgrims into its embrace. The scale, geometric clarity, and symbolic power of the piazza make it one of the world's great public spaces and a masterpiece of urban planning.

Bernini designed several important churches in Rome. Sant'Andrea al Quirinale (1658-1670) is considered one of his architectural gems. A relatively small Jesuit church, it features an oval plan, with the entrance and high altar on the short axis, creating an immediate and dramatic focus. The interior is richly decorated with colored marbles, stucco figures, and gilding, culminating in a sculpted figure of St. Andrew ascending towards the lantern of the dome, another example of the bel composto. The facade, with its convex porch and flanking concave walls, adds to the dynamic interplay of forms.

He also contributed to major palace designs, including the Palazzo Barberini (working alongside Carlo Maderno and Francesco Borromini early in his career), the Palazzo Ludovisi (now Palazzo Montecitorio, later altered), and the Palazzo Chigi-Odescalchi, whose facade influenced palace design across Europe.

Fountains were another area where Bernini excelled, combining sculpture, architecture, and the dynamic element of water. The Fountain of the Four Rivers (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, 1648-1651) in Piazza Navona is perhaps his most famous. Commissioned by Pope Innocent X, it features a central Egyptian obelisk supported by a grotto-like structure of travertine rock, from which emerge allegorical figures representing the four major rivers of the known continents: the Nile, Ganges, Danube, and Río de la Plata. The dynamic poses of the river gods, the realistic depiction of flora and fauna, and the dramatic interplay of rock and water make it a quintessential Baroque spectacle. Other notable fountains include the Triton Fountain (Fontana del Tritone, 1642-43) in Piazza Barberini and the Fountain of the Moor (Fontana del Moro, 1653-54) in Piazza Navona (Bernini designed the central figure).

A Man of Many Talents: Painting, Theatre, and Caricature

Bernini's talents extended beyond sculpture and architecture. While fewer paintings survive, he was a capable painter, primarily active in his earlier years. His self-portraits show a directness and psychological intensity reminiscent of his sculptural busts. He also produced religious paintings and mythological scenes, often influenced by contemporaries like Nicolas Poussin and Andrea Sacchi, though his painterly style remained distinct.

He was deeply involved in the theatre, writing, directing, and designing elaborate stage sets and machines for spectacles, particularly during the reign of Urban VIII. These productions, often performed for the Barberini family, were renowned for their stunning visual effects, integrating perspective scenery, complex machinery for transformations and apparitions, and dramatic lighting – essentially applying his concept of the bel composto to the stage. Though ephemeral, these theatrical works contributed to his fame and demonstrated his holistic approach to art as performance and spectacle.

![The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa [detail] by Gian Lorenzo Bernini](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/113196/m/gian-lorenzo-bernini-the-ecstasy-of-saint-teresa-detail-6111a88d.jpg)

Bernini was also a gifted draftsman and caricaturist. His drawings reveal his working process, often featuring quick, energetic sketches exploring compositional ideas. His caricatures, often witty and incisive sketches of figures at the papal court or notable personalities, show a lighter, observational side to his artistic personality, capturing character with a few deft strokes.

Rivalries, Relationships, and Personal Life

Bernini's dominance in Rome inevitably led to rivalries. His most significant and bitter rival was the architect Francesco Borromini. Both men were geniuses, but possessed vastly different temperaments and artistic approaches. Borromini, more introspective and idiosyncratic, favored complex geometries and undulating forms, often creating spatially inventive but less overtly theatrical works than Bernini. They collaborated briefly at St. Peter's and Palazzo Barberini but soon became fierce competitors, vying for major commissions. Bernini, with his charm, connections, and ability to manage large workshops, often secured the most prestigious projects, which reportedly contributed to Borromini's melancholy and eventual suicide in 1667. Their rivalry defined the architectural landscape of Baroque Rome, offering two contrasting but equally brilliant interpretations of the style.

Bernini also competed with other talented sculptors, notably Alessandro Algardi and the Flemish artist Francois Duquesnoy. Algardi, whose style was more classical and restrained than Bernini's, gained prominence during the papacy of Innocent X (who was initially less favorable to Bernini due to his association with the Barberini). Duquesnoy was renowned for his sensitive rendering of children (putti). However, neither achieved the sustained level of papal favor or the sheer volume and impact of Bernini's output. Bernini also worked with numerous assistants and collaborators, including sculptors like Antonio Raggi and Ercole Ferrata, and painters like Giovan Battista Gaulli (Baciccio), who executed ceiling frescoes within Bernini's architectural frameworks.

His personal life was not without drama. The most notorious incident involved Costanza Bonarelli, the wife of his assistant Matteo. Bernini fell passionately in love with her and sculpted her remarkable bust. Discovering she was also involved with his own brother, Luigi, Bernini flew into a rage, pursued Luigi through the streets of Rome intending to kill him, and later ordered a servant to slash Costanza's face with a razor. While Luigi was exiled and the servant imprisoned, Costanza was imprisoned for adultery. Bernini himself, thanks to the intervention of Pope Urban VIII, escaped serious consequences, being advised to marry. He subsequently married Caterina Tezio in 1639, with whom he had eleven children. His later life was marked by increasing piety.

A significant event later in his career was his trip to Paris in 1665 at the invitation of King Louis XIV, who sought his designs for the rebuilding of the Louvre Palace. While the trip was marked by elaborate ceremony and Bernini created a magnificent bust of the king, his architectural designs for the Louvre were ultimately rejected in favor of a more restrained French classical plan by Claude Perrault. The visit highlighted the growing differences between the exuberant Italian Baroque and the more formal French style.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Despite occasional setbacks, such as the temporary disfavor under Innocent X (during which he created the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa for a private patron) and the French rejection, Bernini remained the preeminent artist in Rome until his death. He continued to receive major commissions under successive popes, including Alexander VII, Clement IX, and Clement X. His workshop remained highly productive, completing projects like the Cathedra Petri (Throne of St. Peter, 1657-66) – an elaborate gilded bronze encasement for a relic chair within St. Peter's Basilica, featuring colossal statues of Doctors of the Church – and the angels lining the Ponte Sant'Angelo (1667-69), leading towards the Vatican.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini died in Rome on November 28, 1680, at the venerable age of 81. He was buried with relative simplicity, alongside his parents, in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. His death marked the end of an era for Roman art. His son, Domenico Bernini, later wrote his biography, Vita del Cavalier Gio. Lorenzo Bernino, published in 1713, which helped shape his posthumous reputation.

Bernini's influence was immense and immediate. He defined the High Baroque style in sculpture and architecture, setting a standard that resonated across Italy and Catholic Europe. His ability to fuse sculpture, architecture, painting, and light into a unified, emotionally charged whole (bel composto) was revolutionary. His dynamic compositions, psychological depth, theatricality, and technical mastery inspired generations of artists. While the subsequent Rococo style softened Baroque drama, and Neoclassicism later reacted against it, Bernini's impact on the urban fabric of Rome and the visual language of religious and secular power remained undeniable. Figures like the Austrian architect Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach and sculptors across Europe show his clear influence. Even artists working in different contexts, like the Spanish master Diego Velázquez, who met Bernini during his visit to Rome, operated within the broader Baroque sensibility that Bernini so powerfully shaped. He remains a pivotal figure, whose works continue to exemplify the energy, passion, and grandeur of the Baroque age.