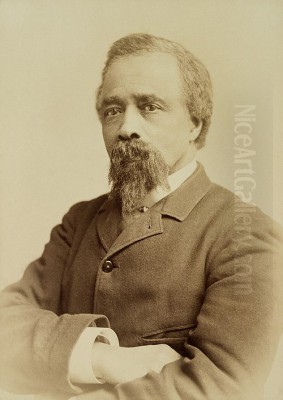

Edward Mitchell Bannister stands as a significant, yet for a long time underappreciated, figure in the landscape of 19th-century American art. An artist of African American and Canadian heritage, he carved out a distinguished career primarily as a painter of serene and evocative landscapes, deeply influenced by the French Barbizon School and a key proponent of the Tonalist aesthetic in America. His journey from humble beginnings to national recognition, particularly his groundbreaking award at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, marks a pivotal moment in the history of African American artists. This exploration delves into the life, artistic style, major achievements, and enduring legacy of a painter who sought to capture the soul of nature on canvas.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Edward Mitchell Bannister was born in 1828 in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada. His father was of Barbadian descent, and his mother was a Black woman from New Brunswick. His early life was marked by the loss of his parents, after which he lived with a white foster family, the Hatch family, who reportedly encouraged his early artistic inclinations. The maritime environment of St. Andrews, with its rugged coastlines and changing atmospheric conditions, likely provided early visual inspiration for the future landscape painter.

In the late 1840s, seeking greater opportunities, Bannister moved to New England, initially working as a cook on ships, which allowed him to travel along the Eastern Seaboard. By the early 1850s, he had settled in Boston, Massachusetts. Boston at this time was a burgeoning cultural center and a hotbed of abolitionist activity. It was here that Bannister began to more seriously pursue his artistic ambitions, despite the significant racial barriers of the era. To support himself, he took up various jobs, including working as a barber and later as a daguerreotypist and photographer, skills which may have honed his eye for composition and light.

Bannister's formal art education was limited but impactful. He attended evening classes at the Lowell Institute, studying drawing and painting under Dr. William Rimmer, a respected artist and anatomist known for his powerful, often dramatic, figural compositions. Rimmer's emphasis on anatomical accuracy and expressive form, though perhaps not directly translated into Bannister's landscape work, would have provided a solid foundation in artistic principles.

The Boston Years: Forging an Artistic Identity

During his time in Boston, Bannister began to establish himself within the local art community, however challenging that might have been for an artist of color. He actively sought out opportunities to learn and exhibit. A significant turning point came with his exposure to the works of the French Barbizon School. An article in the New York Herald in 1867, which disparagingly suggested that Black individuals were incapable of appreciating or creating fine art, reportedly galvanized Bannister, strengthening his resolve to achieve artistic excellence.

The Barbizon School, which included artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny, had shifted landscape painting away from the highly detailed and often grandiose style of earlier academic traditions. Instead, Barbizon painters emphasized intimate, pastoral scenes, a more subjective response to nature, and the depiction of mood and atmosphere through subtle gradations of color and light. William Morris Hunt, a prominent Boston artist who had studied in France and was a fervent admirer of Millet, became a key conduit for Barbizon ideals in New England. Bannister was undoubtedly aware of Hunt's work and the Barbizon paintings increasingly being collected and exhibited in Boston.

Bannister's early works from this period began to reflect these influences. He painted portraits, biblical scenes, and genre subjects, but it was landscape painting that increasingly became his focus. He also engaged with the abolitionist movement, and his art, while not overtly political, can be seen as a quiet assertion of dignity and humanity in a society rife with racial prejudice. In 1857, he married Christiana Carteaux, a successful businesswoman and an influential figure in Boston's Black community, known for her hairdressing salons and her activism. Her support, both financial and emotional, was crucial to Bannister's developing career. During the 1860s, Bannister shared a studio space for a time with Edmonia Lewis, the acclaimed African American and Native American sculptor, further indicating his integration into a small but vital circle of Black artists.

Relocation to Providence: A New Chapter and Artistic Flourishing

In 1870, Edward and Christiana Bannister moved to Providence, Rhode Island. This move marked a significant turning point in Bannister's career and personal life. Providence offered a supportive environment where Bannister's artistic talents could truly flourish. He quickly became a respected member of the city's burgeoning art scene. The Rhode Island landscape, with its gentle hills, meandering rivers, coastal marshes, and picturesque Narragansett Bay, provided ample subject matter perfectly suited to his evolving Tonalist style.

The Tonalist movement, which gained prominence in American art in the latter part of the 19th century, was characterized by its emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and a limited, harmonious palette. Artists like George Inness, Alexander Helwig Wyant, Dwight William Tryon, and Ralph Albert Blakelock were key figures in this movement. Tonalist painters sought to evoke an emotional or spiritual response to nature rather than a purely descriptive one, often depicting scenes at twilight, dawn, or in misty conditions, where forms are softened and details are subsumed by an overall atmospheric effect. Bannister's work aligns closely with these ideals.

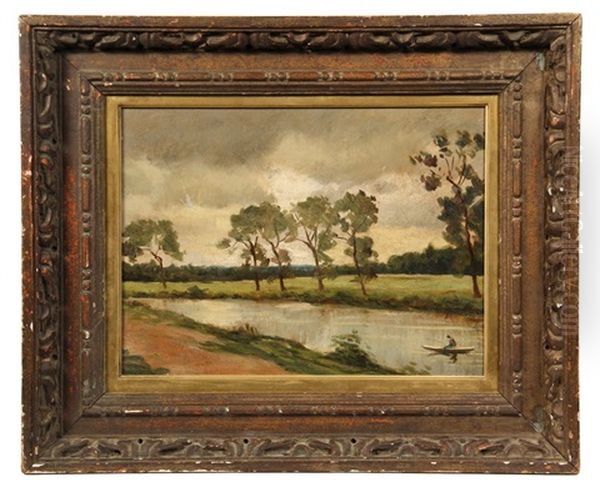

In Providence, Bannister's style matured. He developed a distinctive approach to landscape painting, characterized by soft brushwork, rich but subdued colors, and a profound sense of tranquility. His compositions often featured quiet pastoral scenes, intimate woodland interiors, coastal views, and studies of trees and water under varying light conditions. He was particularly adept at capturing the subtle nuances of light and shadow, creating a poetic and contemplative mood in his paintings. He often worked en plein air, making sketches directly from nature, which he would then develop into finished paintings in his studio. He even purchased a small sailboat, the Fanchon, which he used to explore and sketch the coves and inlets of Narragansett Bay.

The Barbizon Influence and Tonalist Sensibilities

Bannister's deep affinity for the Barbizon School's philosophy and aesthetic is a defining characteristic of his art. He shared their belief in the spiritual and restorative power of nature and their commitment to depicting its humble, everyday beauty. Unlike the grand, often nationalistic, vistas of the earlier Hudson River School artists like Thomas Cole or Frederic Edwin Church, Bannister, much like Corot or Daubigny, focused on more intimate and personal interpretations of the landscape.

His paintings are not typically dramatic or sublime in the manner of Albert Bierstadt's monumental Western landscapes. Instead, they are imbued with a quiet lyricism and a sense of deep contemplation. He masterfully used a palette of greens, browns, grays, and soft blues, often accented with touches of warmer color, to create harmonious and unified compositions. His handling of light is particularly noteworthy; he often depicted the soft, diffused light of early morning or late afternoon, creating a sense of gentle melancholy or peaceful reverie. This approach is a hallmark of Tonalism, where the overall "tone" or mood of the painting takes precedence over precise detail.

Works from his Providence period clearly demonstrate these qualities. He was less concerned with topographical accuracy than with conveying the emotional essence of a scene. Trees are often rendered as soft, feathery masses, water reflects the muted colors of the sky, and human figures, when present, are typically small and integrated into the landscape, suggesting a harmonious coexistence between humanity and nature. This approach can be seen as a form of spiritual expression, reflecting a Transcendentalist-influenced belief in the inherent divinity of the natural world, a sentiment shared by many American artists and writers of the period, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

Under the Oaks and the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition

The year 1876 marked a pinnacle in Edward Bannister's career and a landmark achievement for African American artists. He submitted a large landscape painting, initially titled Oak Trees and later known as Under the Oaks, to the art exhibition of the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, a major international fair celebrating the 100th anniversary of American independence. The painting, a serene pastoral scene measuring five by four feet, depicted a group of figures resting beneath the shade of majestic oak trees.

To Bannister's astonishment, Under the Oaks was awarded a first-prize bronze medal. However, the moment of triumph was initially marred by racial prejudice. When Bannister went to claim his award, the officials, surprised to see a Black man, initially hesitated and considered rescinding it. According to accounts, fellow artists in the exhibition protested this injustice, and the award was ultimately confirmed. This incident, while highlighting the pervasive racism of the era, also underscored the undeniable quality of Bannister's work, which had been judged on its merits by a panel that was unaware of the artist's race.

The success of Under the Oaks brought Bannister national recognition, a remarkable feat for an African American artist at that time. It was a powerful refutation of the racist attitudes that questioned the artistic capabilities of Black people. Sadly, the painting itself was lost for many years after the exhibition, though a photograph of it survives. Its acclaim, however, solidified Bannister's reputation and contributed to his growing influence in the Providence art community. This achievement was not just a personal victory but a symbolic one for the broader African American community, demonstrating that talent and perseverance could overcome even deeply entrenched societal barriers.

Key Works and Artistic Evolution

Throughout his career, Bannister produced a significant body of work, primarily landscapes, but also including seascapes, genre scenes, portraits, and biblical subjects. While Under the Oaks remains his most famous work due to its historical significance, many other paintings exemplify his artistic vision and skill.

_The Newspaper Boy_ (1869): An earlier work, this genre scene, also known as The Newsboy, depicts a young Black newsboy on a city street. It is notable for its sympathetic portrayal of an everyday urban subject and demonstrates Bannister's versatility beyond pure landscape. This painting is now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

_Approaching Storm_ (c. 1886): This painting, also in the Smithsonian, is a quintessential example of Bannister's Tonalist style. It captures the dramatic tension of an impending storm over a coastal landscape, with dark, brooding clouds and a windswept terrain. The use of chiaroscuro and a muted palette effectively conveys the power and mood of nature.

_Sunset_ (1880s): Bannister painted numerous sunset scenes, exploring the fleeting effects of light and color as day transitions into evening. These works are often characterized by their soft, atmospheric qualities and their evocation of a contemplative, almost spiritual, mood.

_Sabin Point, Narragansett Bay_ (1885): This work, in the collection of Brown University, showcases his love for the Rhode Island coastline. It depicts a tranquil view of the bay, with sailboats in the distance and a focus on the interplay of water, sky, and land.

_Palmer River_ (1885): Held by the National Gallery of Art, this painting is a fine example of his mature landscape style, with its lush foliage, calm waters, and harmonious composition, reflecting the Barbizon influence.

_Apple Trees in a Meadow_ (1890): This work captures the idyllic beauty of a rural scene, with blossoming apple trees rendered in soft, impressionistic strokes, showcasing his continued exploration of light and atmosphere.

_Pond Scene_ and _Beach Scene_: These titles represent common themes in his oeuvre, where he explored the reflective qualities of water and the expansive vistas of the coast, always with an eye for capturing the subtle moods of nature.

_After the Shower_ and _Near Lake Quinsigamond_: These works, donated to the Rhode Island School of Design, further illustrate his mastery of atmospheric effects and his ability to imbue ordinary scenes with a sense of poetic beauty.

His style remained relatively consistent throughout his mature period, characterized by a commitment to the Tonalist aesthetic and the Barbizon spirit. He did not embrace the brighter palette and broken brushwork of Impressionism, which was gaining traction in America towards the end of his career, preferring instead the more introspective and atmospheric qualities of Tonalism.

Founding the Providence Art Club and Community Leadership

Beyond his personal artistic achievements, Edward Bannister played a crucial role in fostering the growth of the arts community in Providence. In 1880, he was a co-founder of the Providence Art Club, along with other prominent local artists such as George William Whitaker and Charles Walter Stetson. The Providence Art Club quickly became a vital institution for artists in the region, providing a venue for exhibitions, lectures, and social gatherings. Bannister served on its initial board of directors and remained an active and respected member throughout his life.

His involvement with the Providence Art Club demonstrates his commitment to creating a supportive environment for fellow artists and promoting art appreciation within the community. He was also one of the founding board members of the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 1877, an institution that would go on to become one of the leading art and design colleges in the United States. His participation in the founding of these key institutions underscores his leadership and his dedication to the cultural enrichment of his adopted city.

Bannister was known for his gentle demeanor, his intellectual curiosity, and his willingness to mentor younger artists. Charles Walter Stetson, for instance, considered Bannister a significant influence and "his only art-confidant in art matters." Bannister's home, shared with his accomplished wife Christiana, became a gathering place for artists, writers, and intellectuals, fostering a vibrant cultural milieu.

A Mentor and a Mariner

Bannister's role as a mentor extended beyond formal institutional settings. He was generous with his time and knowledge, encouraging aspiring artists and sharing his insights into the creative process. His own dedication to continuous learning and artistic exploration served as an example to others. He was an avid reader and was well-versed in literature, poetry, and philosophy, which informed the intellectual depth of his art.

His passion for the sea and for sailing was another important aspect of his life and work. His sailboat, the Fanchon, was not merely a recreational vessel but an essential tool for his artistic practice. It allowed him to access remote coastal areas, observe the changing conditions of the sea and sky firsthand, and make sketches that would later inform his studio paintings. This direct engagement with the marine environment contributed to the authenticity and evocative power of his seascapes and coastal scenes. The freedom and solitude he found while sailing may also have provided a necessary respite and a source of inspiration, allowing him to connect deeply with the natural world that was his primary subject.

Navigating a Prejudiced World

It is impossible to discuss Edward Bannister's life and career without acknowledging the profound challenges he faced as a Black artist in 19th-century America. Despite his talent and achievements, he constantly navigated a society deeply ingrained with racial prejudice. The incident at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition is a stark reminder of this reality. While he achieved a level of recognition and acceptance within the Providence art community, the broader art world and society at large often marginalized artists of color.

His decision to primarily focus on landscape painting, rather than overtly political or narrative subjects related to the Black experience, has been interpreted in various ways. Some scholars suggest it was a strategic choice, allowing him to gain acceptance in a predominantly white art world where "Negro subjects" might have been less marketable or viewed through a stereotypical lens. Others argue that his choice reflected a genuine personal and artistic inclination towards the universal themes of nature, beauty, and spirituality, aligning with the prevailing Tonalist and Barbizon aesthetics. It is likely that both factors played a role. His landscapes, in their quiet dignity and profound beauty, can be seen as a subtle but powerful assertion of his artistic vision and his humanity, transcending the racial categorizations of his time.

His wife, Christiana Carteaux Bannister, was a formidable figure in her own right. A successful entrepreneur and activist, she was a staunch supporter of abolitionism and women's rights. Her business acumen provided financial stability, allowing Edward to pursue his art, and her social connections and activism likely helped to create a supportive network for him. She was also instrumental in establishing the Home for Aged Colored Women in Providence.

Later Years and Final Days

Edward Bannister continued to paint and exhibit actively throughout the 1880s and 1890s, maintaining his commitment to his Tonalist style. He remained a respected figure in the Providence art scene, though, like many artists of his generation whose styles were superseded by newer movements like Impressionism, his national prominence may have waned somewhat in his later years.

His health began to decline in the late 1890s. On January 9, 1901, while attending a prayer meeting at his church, the Elmwood Avenue Baptist Church in Providence, Edward Mitchell Bannister suffered a heart attack and passed away. He was approximately 72 years old. His death was mourned by the Providence community, who recognized his significant contributions as an artist and a citizen. He was buried in the North Burial Ground in Providence.

His friends and fellow artists remembered him for his gentle nature, his intellectual depth, and his unwavering dedication to his art. Despite the challenges he faced, he had forged a successful career and left behind a substantial body of work that testified to his unique artistic vision.

Rediscovery and Legacy

Following his death, Edward Bannister's work, like that of many Tonalist painters, fell into relative obscurity for several decades as artistic tastes shifted towards Modernism. The contributions of African American artists, in general, were often overlooked by mainstream art history during this period.

However, beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement and a renewed interest in re-evaluating and broadening the canon of American art, scholars and curators began to rediscover Bannister's work. Exhibitions and publications dedicated to African American art brought his achievements to a new generation. His pioneering role as the first African American artist to win a major national award was recognized, and the quality and beauty of his paintings were reassessed.

Today, Edward Mitchell Bannister is acknowledged as a significant American artist of the 19th century. His works are held in the collections of major museums, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Rhode Island School of Design Museum. His paintings are admired for their poetic beauty, their subtle atmospheric effects, and their profound connection to the natural world.

His legacy extends beyond his artistic output. He stands as an inspiring figure who overcame significant racial barriers to achieve excellence in his chosen field. He helped to pave the way for future generations of African American artists, including figures like Henry Ossawa Tanner, who achieved international acclaim, and later artists of the Harlem Renaissance such as Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence. Bannister's success demonstrated that artistic talent knows no racial boundaries.

Bannister and His Contemporaries: A Wider View

To fully appreciate Bannister's place in art history, it is useful to consider him in the context of his contemporaries. His Barbizon-influenced Tonalism set him apart from the more detailed realism of the later Hudson River School painters like Sanford Robinson Gifford or John Frederick Kensett, though he shared their love for the American landscape.

His work shows affinities with other American Tonalists such as George Inness, whose landscapes similarly emphasized mood and spiritual content, and Alexander Helwig Wyant, known for his poetic woodland scenes. While James McNeill Whistler, another contemporary, also explored Tonalist principles in his "Nocturnes," Whistler's work was often more overtly concerned with aestheticism and formal arrangement ("art for art's sake"). Bannister's Tonalism remained more grounded in a direct, emotional response to nature.

Compared to other prominent African American artists of the 19th century, Bannister's focus on landscape was distinctive. Robert S. Duncanson, an earlier African American landscape painter, also achieved considerable success, often working in a style influenced by the Hudson River School and European Romanticism. Edmonia Lewis, his contemporary in Boston, gained international fame for her neoclassical sculptures on themes related to her African American and Native American heritage. Henry Ossawa Tanner, a younger contemporary, became renowned for his deeply moving religious paintings and scenes of everyday life in North Africa and the Middle East, often characterized by their rich color and dramatic lighting. Other early figures include the portraitist Joshua Johnson and the landscape painter and lithographer Grafton Tyler Brown.

Bannister's circle in Providence included artists like George William Whitaker, a landscape and marine painter, and Charles Walter Stetson, known for his imaginative and symbolic works. These local connections were vital for mutual support and artistic exchange. His engagement with these artists, and his leadership in founding the Providence Art Club, highlight his role as a community builder.

Conclusion: An Enduring Voice

Edward Mitchell Bannister's art offers a window into a soul that found solace, beauty, and spiritual meaning in the natural world. His landscapes are not mere depictions of scenery but are imbued with a profound sense of peace and contemplation. Working within the traditions of the Barbizon School and American Tonalism, he developed a distinctive lyrical voice, capturing the subtle moods and atmospheric effects of the New England countryside and coastline.

His achievement in winning a medal at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition was a watershed moment, challenging racial prejudice and affirming the talent of African American artists on a national stage. Despite the societal obstacles he faced, Bannister persevered, creating a significant body of work and contributing to the cultural life of his community as an artist, mentor, and leader.

Today, Edward Mitchell Bannister is rightfully recognized as an important figure in American art history. His paintings continue to resonate with viewers, inviting them to share in his quiet, poetic vision of nature. His life and work stand as a testament to the power of art to transcend barriers and to express the deepest human emotions and spiritual aspirations. He remains an inspiration, not only for his artistic achievements but for his quiet dignity and unwavering commitment to his craft in the face of adversity.