Edward Barnard Lintott stands as an intriguing, if somewhat understated, figure in the annals of early to mid-20th-century art. A British-born artist who found a significant part of his career unfolding in the United States, Lintott specialized in portraiture, developing a distinctive style characterized by its subtle atmospherics and focused psychological insight. His work, though perhaps not as widely celebrated today as some of his more bombastic contemporaries, offers a quiet testament to the enduring power of traditional painting techniques adapted to a modern sensibility.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in London, England, in 1875, Edward Barnard Lintott's artistic journey began in his native country. While specific details of his earliest training can be elusive, it is known that he, like many aspiring artists of his generation, would have been exposed to the rich artistic traditions of Europe. London at the turn of the century was a vibrant hub, with institutions like the Royal Academy of Arts setting a high standard, and influential figures such as John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler demonstrating vastly different but equally compelling approaches to painting, particularly portraiture.

It is highly probable that Lintott absorbed lessons from the academic tradition, which emphasized strong draftsmanship and a faithful representation of the subject. However, the atmospheric qualities later evident in his work also suggest an awareness of movements like Tonalism, championed by Whistler, which prioritized mood and harmony of color over precise detail. Many artists of this period also sought training in Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. Lintott indeed studied at the prestigious Académie Julian and also at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, under masters like Jean-Paul Laurens and Benjamin Constant, and later with William-Adolphe Bouguereau. He also spent time at the British Academy in Rome and the National College of Art in South Kensington, London. This Continental exposure would have broadened his artistic horizons considerably, exposing him to Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the nascent stirrings of modernism.

Transatlantic Passages and a Developing Style

At some point in his career, Lintott made the significant move to the United States, eventually becoming a naturalized citizen. This transatlantic shift placed him within a new and dynamic artistic environment. The American art scene in the early 20th century was a melting pot of influences, with artists grappling with European modernism while also seeking to forge a distinctly American artistic identity. Figures like Robert Henri, a leading member of the Ashcan School, were advocating for a grittier, more realistic depiction of urban life, while others were experimenting with abstraction.

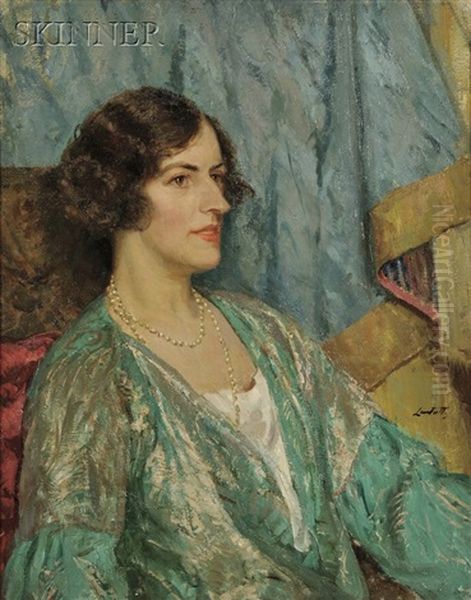

Lintott, however, largely remained committed to representational art, particularly portraiture. His style, as described, involved creating a "dimly lit atmosphere," using "soft light" to highlight the figure, and minimizing background details. This approach served to concentrate the viewer's attention squarely on the sitter, allowing for a more intimate and often introspective portrayal. Such a technique shares affinities with the work of earlier masters like Rembrandt, who used chiaroscuro to dramatic and psychological effect, but Lintott's application seems to have been softer, more diffused, perhaps echoing the subtle gradations of Whistler or the quiet dignity found in the portraits of Thomas Eakins.

His portraits were not merely about capturing a likeness; they aimed to convey character and mood. By subduing the background, Lintott stripped away potential distractions, forcing a direct engagement with the individual. The "soft light" would have modeled the features gently, avoiding harshness and perhaps imbuing his subjects with a sense of quiet contemplation or refined presence. This was a sophisticated approach that stood somewhat apart from the bolder, more declarative styles of some of his American contemporaries like George Bellows or the Regionalists such as Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, who often favored more dynamic compositions and brighter palettes.

"Clown with Butterfly": A Representative Work

Among Lintott's known works, "Clown with Butterfly," painted in 1932, stands out, particularly as it was featured in a significant exhibition. This oil on canvas, measuring 30 x 25 inches, encapsulates many of the stylistic and thematic elements associated with his art. The subject of the clown has a long and rich history in art, often used as a vehicle for exploring themes of melancholy, performance, and the human condition. Artists from Watteau to Picasso, and notably Georges Rouault, have been drawn to the figure of the clown or pierrot, finding in its painted smile and costumed artifice a poignant counterpoint to inner sadness or societal critique.

Lintott's choice of a clown, paired with a butterfly, suggests a composition rich in potential symbolism. The butterfly, often a symbol of transformation, beauty, and fragility, could offer a delicate contrast to the perhaps more robust or melancholic figure of the clown. The "dimly lit atmosphere" and "soft light" characteristic of Lintott's style would have been particularly effective in rendering such a subject. One can imagine the gentle illumination picking out the textures of the clown's costume, the subtle expression on his face, and the delicate wings of the butterfly, all set against a muted, non-descript background that pushes the figures forward, demanding the viewer's engagement.

The painting was lent by Lintott himself for exhibition, indicating his own regard for the piece. Its subject matter, while not overtly "American Scene," resonated with a broader modernist interest in figures from the world of entertainment and their underlying human complexities. It speaks to an artist engaged with character study and capable of imbuing a traditional genre with a quiet, modern sensibility.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Edward Barnard Lintott's work was showcased in several important venues, indicating a degree of recognition within the art world of his time. His participation in the "Century of Progress Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture" in 1933 is particularly noteworthy. This exhibition was part of the Chicago World's Fair, a massive international event that aimed to showcase advancements in science, industry, and culture. The art component was significant, presenting a survey of contemporary art to a vast public. For "Clown with Butterfly" to be included in such a prestigious show suggests that Lintott's work was considered of merit and representative of current artistic practice. He exhibited alongside a diverse array of artists, likely including American modernists, regionalists, and more traditional painters. Other artists whose works were featured in such large-scale American exhibitions of the era included figures like Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, Reginald Marsh, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi.

Furthermore, Lintott participated in an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in its original West Eighth Street location, from January 24 to February 13, 1936. The Whitney, founded by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, was (and remains) dedicated to promoting American art and artists. To be exhibited at the Whitney was a significant acknowledgment for any artist working in the United States. This particular exhibition would have featured a cross-section of American artists, reflecting the museum's commitment to contemporary practice. His inclusion places him in the company of artists who were shaping the landscape of American art in the 1930s, a period marked by the Great Depression, the rise of Social Realism, and continued explorations of modernism. Contemporaries who were also being shown at the Whitney around this period included Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and Georgia O'Keeffe, though their styles were often vastly different from Lintott's more traditional approach.

The record also indicates that Lintott painted a portrait of a Dwight Johnson in 1940, and there is mention of correspondence with Etta Cone, one of the famous Cone sisters of Baltimore, renowned collectors of modern art, particularly Matisse. This suggests Lintott moved within artistic and collecting circles, engaging with patrons and fellow art enthusiasts.

Artistic Context and Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Lintott's contribution, it's useful to consider him within the broader artistic currents of his time. In Britain, during his formative years, the art scene was still feeling the impact of late Victorian academicism, but also the aestheticism of Whistler and the burgeoning modernism influenced by French Post-Impressionism, championed by critics like Roger Fry who organized seminal exhibitions of Manet and the Post-Impressionists in London in 1910 and 1912. Artists like Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group were exploring urban themes with a darker, more modern palette.

Upon moving to America, Lintott would have encountered a different artistic landscape. The Armory Show of 1913 had introduced European avant-garde art to a sometimes shocked American public, and its reverberations were still being felt. While some American artists embraced abstraction and Fauvism, others, like the American Scene painters (Benton, Wood, John Steuart Curry), turned to depictions of rural and regional American life. Portraiture continued to be a strong tradition, with artists like Cecilia Beaux maintaining a high standard, and others like Wayman Adams capturing prominent figures with a vigorous style.

Lintott's approach to portraiture, with its emphasis on mood and subtle lighting, might be seen as a continuation of the refined, introspective tradition of artists like Thomas Wilmer Dewing or even some aspects of the Boston School painters like Edmund C. Tarbell or Frank Weston Benson, though they often focused on idealized female figures in interiors. His work seems less concerned with bravura brushwork, like that of Sargent or a contemporary like Leopold Seyffert, and more with a quiet, sustained observation.

His dedication to a more traditional, albeit atmospheric, form of representation meant he was somewhat distinct from the more radical innovators of his time. He was not an avant-gardist in the vein of Arthur Dove or Max Weber, nor a stark realist like Charles Sheeler. Instead, he carved out a niche for himself as a skilled portraitist who could convey psychological depth through a refined and understated visual language.

Later Career and Legacy

Information about Lintott's later career, after the 1930s and 40s, is less prominent in the provided summary. He passed away in 1951. Like many artists whose styles do not align with the dominant narratives of avant-garde progression, his work may have been somewhat overshadowed by the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the post-war years. However, the enduring appeal of well-executed portraiture and the quality of his documented works ensure his place in the history of 20th-century representational art.

His participation in significant exhibitions like the Century of Progress and at the Whitney Museum indicates that he achieved a notable level of professional success and recognition during his lifetime. His ability to capture the essence of his sitters through a subtle interplay of light and shadow, and his focus on the human subject in an era increasingly drawn to abstraction or social commentary, marks him as an artist of sensitivity and skill.

The legacy of artists like Edward Barnard Lintott lies in their contribution to the diverse tapestry of art history. Not every artist needs to be a revolutionary; there is immense value in those who master their craft and apply it with intelligence and feeling to established genres. Lintott's portraits, exemplified by works like "Clown with Butterfly," offer a window into the individuals he depicted and into the artistic sensibilities of his time. They remind us of the quiet power of observation and the nuanced portrayal of human character. His work warrants further study to fully appreciate his position as a transatlantic artist who navigated the currents of tradition and modernity in the early 20th century. His paintings serve as a bridge, connecting the rich heritage of European portraiture with the evolving artistic identity of America.