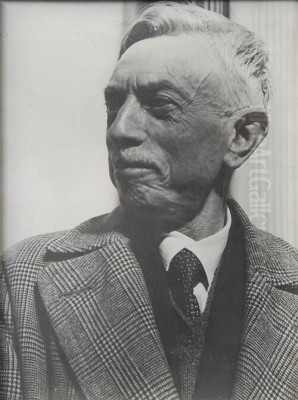

Léon Spilliaert stands as a unique and compelling figure in early 20th-century European art. A Belgian Symbolist and precursor to Expressionism, he navigated a singular path, largely self-taught, creating a body of work steeped in introspection, melancholy, and the haunting atmosphere of his coastal hometown, Ostend. Born on July 28, 1881, and passing away on November 23, 1946, Spilliaert's life spanned a period of immense artistic upheaval, yet his vision remained intensely personal, exploring the depths of the human psyche against the backdrop of desolate landscapes and shadowy interiors. His art, often rendered in stark contrasts of light and dark using ink, watercolour, and pastel, captures a profound sense of solitude and existential questioning that continues to resonate with viewers today.

Early Life and the Shaping of an Artist

Léon Spilliaert was born in Ostend, a bustling Belgian port city on the North Sea coast. His father, Léonard-Hubert Spilliaert, was a successful perfumer and hairdresser who supplied the Belgian royal court, providing a comfortable bourgeois upbringing for Léon and his siblings. His mother, Léonie Jonckheere, was known for her gentle nature. Despite this comfortable background, young Léon was marked by a sensitive, introspective temperament and plagued by poor health from an early age, particularly chronic stomach ailments and severe insomnia.

These health issues significantly impacted his education and artistic development. While he briefly attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Bruges in 1899, he found the traditional academic training stifling and ill-suited to his disposition. He left after only a few months, choosing instead to pursue his artistic path independently. This decision set the stage for a career defined by self-reliance and a unique, unmediated approach to art-making.

His formative years were spent absorbing the sights and sounds of Ostend. The vast expanse of the North Sea, the long promenades, the stark geometry of the dykes and piers, and the often-grey, windswept atmosphere of the coastal town deeply imprinted themselves on his artistic consciousness. His insomnia frequently led him on solitary nocturnal walks through the deserted streets and along the seafront, experiences that would directly fuel the imagery and mood of his most iconic works. The emptiness, the artificial lights casting long shadows, and the profound silence of the night became recurring motifs.

The Influence of Literature and Philosophy

Spilliaert was an avid reader with a profound intellectual curiosity. He was deeply drawn to the works of Symbolist writers and existentialist philosophers whose ideas resonated with his own introspective nature and preoccupation with themes of alienation, anxiety, and the human condition. Key among these influences were the American master of the macabre, Edgar Allan Poe, and the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Poe's tales of psychological horror, mystery, and the uncanny found a visual echo in Spilliaert's shadowy interiors, distorted perspectives, and sense of impending dread. The atmosphere of Poe's writing, laden with melancholy and a fascination with the darker aspects of the human mind, aligned perfectly with Spilliaert's artistic sensibilities. He explored similar territories of fear, loneliness, and the fragility of sanity.

Nietzsche's philosophical explorations of individualism, the critique of conventional morality, and the concept of the abyss also left a significant mark. Spilliaert seemed particularly drawn to the philosopher's emphasis on confronting uncomfortable truths and exploring the depths of existence. This philosophical underpinning can be felt in the starkness and existential weight of many of Spilliaert's compositions, particularly his self-portraits, which often convey a sense of intense self-scrutiny and confrontation with the void.

His literary inclinations led him to seek work in Brussels around 1900 with the renowned Symbolist publisher Edmond Deman. Deman, who published works by key figures of the Belgian Symbolist movement like Émile Verhaeren and Maurice Maeterlinck, employed Spilliaert primarily as an illustrator. This role allowed Spilliaert to engage directly with contemporary literature and further refine his graphic style, working predominantly in ink and watercolour to create illustrations that captured the mood and essence of the texts.

Forging a Unique Visual Language

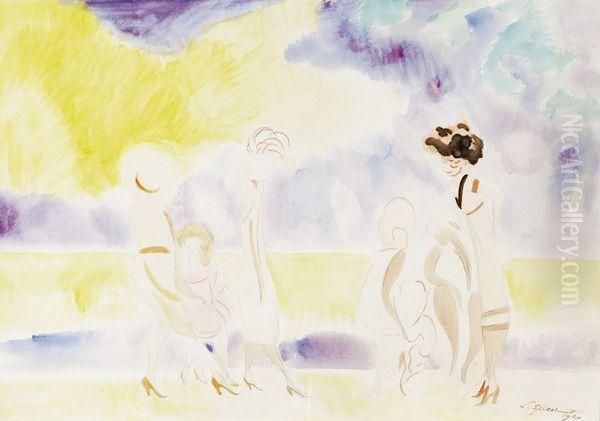

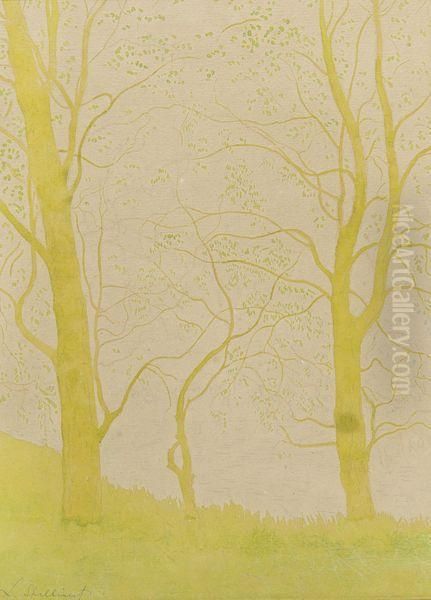

Working largely outside the established art institutions, Spilliaert developed a highly personal and instantly recognizable style. He favoured relatively inexpensive and fluid media like Indian ink, watercolour, gouache, chalk, and coloured pencils, often combining them on paper or cardboard. He rarely worked in oil paint, preferring the immediacy and expressive potential of drawing and water-based techniques.

His visual language is characterized by stark contrasts, simplified forms, and a masterful command of line and tone. He often employed dramatic perspectives, using steep diagonals and geometric compositions to create unsettling spatial effects and enhance the emotional impact of his scenes. Empty spaces play a crucial role in his work, evoking feelings of silence, isolation, and vastness, whether depicting a deserted street, an empty room, or the infinite horizon of the sea.

Light and shadow are fundamental elements in Spilliaert's art. He used light not merely for illumination but as an active force, often artificial and harsh, casting long, distorted shadows that contribute to the dreamlike or nightmarish quality of his images. His palette was frequently restricted, dominated by blacks, greys, deep blues, and sombre earth tones, punctuated occasionally by unexpected flashes of brighter colour. This restrained use of colour enhances the graphic power and emotional intensity of his work.

His technique involved applying washes of ink or watercolour, sometimes blotting or wiping them to achieve specific textures and tonal variations. His line work could range from delicate and precise to bold and expressive, always serving to define form and convey feeling. This combination of technical skill and emotional depth marks him as a bridge figure between the introspective mood of Symbolism and the burgeoning energy of Expressionism.

Ostend: Muse and Melancholy Setting

Ostend was more than just Spilliaert's birthplace; it was his primary muse, the source of his most powerful and enduring imagery. He returned to the city's motifs throughout his career, finding in its familiar landscapes an objective correlative for his inner world. The Royal Galleries, the long dyke stretching along the coast, the deserted beaches under moonlight or stormy skies, the Kursaal (casino), and the empty streets at night became the stage for his explorations of solitude and existential unease.

His famous work often titled Digue la nuit (Dyke at Night) or sometimes associated with the title Vertigo (c. 1908) exemplifies his Ostend nocturnes. It depicts a lone, silhouetted figure, often interpreted as the artist himself, standing at the top of a steeply receding colonnade or walkway along the seafront at night. The exaggerated perspective creates a dizzying sense of unease, while the stark contrast between the artificial lights and the deep shadows evokes profound isolation and perhaps a confrontation with the vast darkness of the sea and the night.

Other works capture the emptiness of the beach, the rhythmic patterns of breakwaters receding into the sea, or the stark silhouettes of buildings against a luminous or threatening sky. He painted the sea itself, La Mer, not in the Impressionistic manner of capturing fleeting light effects, but as a powerful, often menacing force, reflecting his own turbulent inner state. Even seemingly mundane subjects like La Poste (The Post Office) are imbued with a sense of mystery and quiet alienation through his distinctive use of composition and atmosphere.

His intimate knowledge of the town, gained through countless walks, especially during his sleepless nights, allowed him to distill its essence into potent visual metaphors. Ostend in Spilliaert's art is not a picturesque seaside resort but a place of profound solitude, a liminal space between land and sea, light and darkness, reality and dream.

The Intense Gaze: Spilliaert's Self-Portraits

Throughout his career, particularly in the early years between 1903 and 1908, Spilliaert produced a remarkable series of self-portraits. These are among his most intense and psychologically probing works, offering a raw and unflinching look at the artist's inner turmoil. Rendered primarily in ink wash, watercolour, and crayon, they depict him with haunting, wide-eyed stares, often confronting the viewer directly or gazing into a mirror.

These self-portraits go far beyond mere likeness. They are explorations of identity, anxiety, and the artist's own sense of alienation. He often used mirrors, sometimes creating complex compositions with multiple reflections, suggesting fragmented identities or the disorienting nature of self-perception. The lighting is typically dramatic, carving his features out of darkness, emphasizing his gaunt face, prominent forehead, and piercing eyes, which seem to hold both vulnerability and a startling intensity.

In works like Self-Portrait with Blue Sketchbook (1907) or Self-Portrait in the Mirror (1908), the background is often reduced to simple, abstract planes or deep shadow, focusing all attention on the artist's face and psychological state. The starkness of the execution, combined with the emotional charge of his gaze, makes these self-portraits powerful documents of introspection, comparable in intensity to those of other masters of self-examination like Rembrandt van Rijn or Edvard Munch. They reveal his preoccupation with his own physical frailty and the existential questions that haunted him.

Paris, Verhaeren, and Artistic Encounters

Around 1904, Spilliaert spent time in Paris, hoping to find greater opportunities and immerse himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of the French capital. While Paris was then the epicentre of avant-garde movements like Fauvism and early Cubism, Spilliaert remained somewhat detached, pursuing his own introspective path. However, his time there was significant, particularly through his connection with the influential Belgian Symbolist poet Émile Verhaeren.

Verhaeren became a crucial supporter and friend. He admired Spilliaert's work, purchased several pieces, and helped introduce him to other artists and writers in his circle. This connection provided Spilliaert with valuable encouragement and a link to the broader Symbolist movement. Verhaeren's own poetry, often dealing with themes of modern life, social change, and the power of nature, likely resonated with Spilliaert's sensibilities.

While in Paris, Spilliaert would have been aware of the radical artistic experiments taking place. Artists like Henri Matisse were revolutionizing the use of colour, while Pablo Picasso was embarking on his journey towards Cubism. Although Spilliaert's style remained distinct, the energy and innovation of the Parisian scene may have subtly informed his work. Some sources mention encounters or awareness of figures like Picasso, though Spilliaert's introverted nature meant he was not deeply integrated into the bohemian café society frequented by many avant-garde artists like Amedeo Modigliani or André Derain.

His primary artistic affinities remained closer to the Symbolist and Expressionist currents emanating from Northern Europe. He shared a spiritual kinship with fellow Belgian James Ensor, another Ostend-based artist known for his masks, skeletons, and critique of bourgeois society, though Spilliaert's work was generally less satirical and more introspective. The influence of Norwegian artist Edvard Munch is often cited, particularly in the shared themes of anxiety, loneliness, and psychological intensity, as well as certain stylistic devices like expressive line and evocative use of colour. Spilliaert's work also finds echoes in the dreamlike atmospheres of Odilon Redon and the melancholic symbolism of fellow Belgians like Fernand Khnopff or the earlier generation of Symbolists such as Gustave Moreau or Arnold Böcklin. He also admired the atmospheric nocturnes of James McNeill Whistler.

Key Themes and Recurring Motifs

Several core themes and motifs run through Léon Spilliaert's oeuvre, reflecting his consistent preoccupations. Solitude is perhaps the most pervasive theme, evident in his depictions of lone figures, empty landscapes, and deserted interiors. This solitude is often tinged with melancholy, anxiety, or a sense of existential dread, reflecting the artist's own temperament and his engagement with the philosophical currents of his time.

The sea and the coastline of Ostend are central motifs, serving as powerful symbols of nature's immensity, indifference, and potential for both beauty and terror. The interplay of light and darkness, particularly the artificial lights of the city at night against the vast darkness of the sea or sky, is another recurring element, used to create mood and explore psychological states.

Interiors also feature prominently, often depicted as sparse, claustrophobic spaces imbued with a sense of unease or waiting. Objects within these interiors – chairs, tables, mirrors, windows – take on a symbolic weight, contributing to the overall atmosphere of silence and introspection. Reflections, particularly in mirrors and water, are used to explore themes of identity, perception, and the boundary between reality and illusion.

Later in his career, particularly after his marriage in 1916 to Rachel Vergison and his move away from Ostend during World War I, some shifts occurred. While the core introspection remained, some works showed a slightly lighter palette or focused on different subjects, including more serene landscapes or domestic scenes. However, the fundamental exploration of inner states through external imagery remained consistent. Works like Arbre (Tree) show his continued fascination with nature, often imbued with symbolic meaning.

Later Life, Legacy, and Recognition

Spilliaert spent the war years in Brussels and Geneva, returning periodically to Ostend. He married Rachel Vergison in 1916, and their daughter Madeleine was born the following year. Family life brought a degree of stability, though his introspective nature and dedication to his art remained constants. He continued to exhibit his work, primarily in Belgium, gaining respect within artistic circles but never achieving widespread fame during his lifetime.

He settled permanently in Brussels in 1935, continuing to work until his death from heart problems on November 23, 1946, at the age of 65. For several decades after his death, Spilliaert remained a somewhat overlooked figure outside of Belgium, overshadowed by the more radical movements of the 20th century.

However, beginning in the later 20th century and accelerating into the 21st, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in his work. Major retrospectives in Brussels, Paris, and notably at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 2020, have brought his unique vision to a wider international audience. Critics and art historians now recognize him as a major figure of Belgian Symbolism and a significant precursor to Expressionism, praising his technical mastery, psychological depth, and the haunting originality of his art.

His influence can be seen in the work of later artists drawn to themes of solitude and introspection. His ability to convey profound emotional states through stark, atmospheric imagery continues to captivate viewers. Spilliaert's legacy lies in his creation of a deeply personal visual world that explores the anxieties and mysteries of modern existence with haunting beauty and unflinching honesty.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Léon Spilliaert remains a singular voice in the landscape of modern European art. A self-taught visionary, he transformed his personal struggles with insomnia and ill health, his introspective temperament, and the unique atmosphere of his hometown into a powerful and enduring body of work. His mastery of line and tone, his evocative use of light and shadow, and his unflinching exploration of solitude, anxiety, and the human psyche mark him as a crucial link between Symbolism and Expressionism. Though often working in isolation, his art speaks to universal human experiences, capturing the quiet dread and profound beauty found in the liminal spaces between night and day, land and sea, the self and the void. Today, Spilliaert is rightly recognized as one of Belgium's most important modern artists, whose haunting images continue to exert a powerful fascination.