Jan Mankes stands as a unique and cherished figure in early 20th-century Dutch art. Though his life was tragically short, his artistic output, characterized by an almost spiritual delicacy and profound intimacy, has left an indelible mark. His paintings, drawings, and prints, often depicting the quiet beauty of nature, animals, and introspective human subjects, resonate with a timeless quality that continues to captivate audiences. This exploration delves into the life, artistic style, influences, and enduring legacy of a painter who, in his brief career, crafted a world of serene contemplation.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on August 15, 1889, in Meppel, a town in the Dutch province of Drenthe, Jan Mankes displayed an early inclination towards the arts. His formative years were not spent in the bustling art centers of Amsterdam or Paris, but in more secluded environments that would deeply shape his artistic sensibility. His family later moved to Delft, a city historically rich in artistic heritage, being the home of Johannes Vermeer. It was here, around 1904, that Mankes began a practical apprenticeship at the Prinsenhof studio, learning the craft of stained-glass painting under the guidance of Jan Schouten and later Hermanus Veldhuis. This early training in a decorative art form likely contributed to his meticulous attention to detail and his understanding of light and color.

However, the structured world of stained-glass design did not fully satisfy Mankes's burgeoning desire for personal artistic expression. By 1908, he made the pivotal decision to become an independent artist. He chose to leave the urban environment and returned to the more rural setting of Friesland, specifically to De Knipe (also known as Den Nyp). This move signaled a deliberate retreat from the mainstream art world, allowing him to cultivate his unique vision in relative isolation, surrounded by the landscapes and creatures that would become his primary subjects. This self-imposed solitude was crucial for the development of his introspective style.

The Development of a Unique Style

Mankes's artistic style is often described as a blend of Symbolism and a highly refined, almost ethereal Realism. He was not an artist of grand gestures or dramatic narratives. Instead, his genius lay in his ability to capture the subtle essence of his subjects, imbuing them with a quiet intensity and a sense of inner life. His technique was characterized by meticulous brushwork, often applying thin layers of paint to achieve a delicate, translucent quality. This approach lent his works a luminous, almost fragile appearance.

He was known to work extensively from memory, internalizing his subjects through intense observation before committing them to canvas or paper. This method allowed him to distill the essential characteristics of what he saw, rather than merely transcribing visual data. His palette, while sometimes employing bright, clear colors, often leaned towards muted tones and subtle gradations, creating an atmosphere of tranquility and contemplation. There's a palpable stillness in his work, a sense of a moment held in perfect, quiet suspension. This meditative quality set him apart from many of his contemporaries who were exploring more radical, avant-garde styles.

Key Themes and Subjects

The natural world was Mankes's most profound and consistent source of inspiration. Birds, in particular, held a special fascination for him. He depicted owls, falcons, sparrows, and other avian species with an extraordinary sensitivity, capturing not just their physical likeness but also their inherent wildness and delicate beauty. His famous painting, Owl on a Branch (1911), exemplifies this, showcasing the creature with a focused intensity against a subtly rendered background. These were not mere ornithological studies; they were portraits of individual beings, imbued with personality and a sense of quiet dignity.

Animals, too, featured prominently, with works like Two Mice (1916) demonstrating his ability to find profound beauty in the smallest of creatures. He rendered them with the same care and respect he afforded his human subjects. His landscapes, often depicting the serene, flat countryside of Friesland or Gelderland, are imbued with a poetic stillness. They are not dramatic vistas but intimate glimpses of nature, often veiled in soft light or mist.

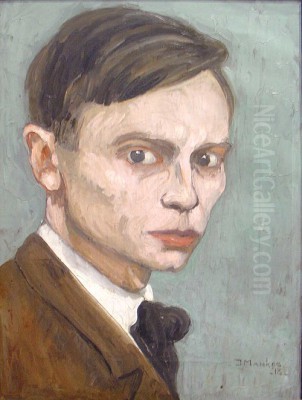

Portraits, including several poignant self-portraits, reveal another facet of his talent. His Self-Portrait with Owl (1911) and other self-renderings show a young man of intense gaze and quiet introspection. His human subjects are often depicted in contemplative poses, their inner worlds hinted at rather than explicitly revealed. Throughout his oeuvre, whether depicting a bird, a landscape, or a human face, Mankes sought to convey a sense of the fragile, transient beauty of life.

Influences: Dutch Masters and Beyond

While Mankes developed a highly personal style, he was not immune to the artistic currents and historical precedents around him. The legacy of the Dutch Golden Age painters, particularly Johannes Vermeer and Carel Fabritius, is often cited as an influence. The quiet domesticity, masterful handling of light, and psychological depth found in Vermeer's work, and the delicate precision of Fabritius (especially his famous Goldfinch), find echoes in Mankes's own meticulous technique and intimate subject matter. He shared their profound respect for the observed world and their ability to elevate the mundane to the poetic.

Among more contemporary influences, Vincent van Gogh's expressive power and deep connection to nature, though stylistically very different, may have resonated with Mankes's own artistic temperament. While Mankes's art lacked Van Gogh's turbulent emotionalism, both artists shared a profound empathy for their subjects and a desire to convey an inner truth.

Furthermore, Mankes was aware of and appreciated Japanese art, particularly the woodblock prints of artists like Katsushika Hokusai. The refined compositions, attention to natural detail, and often asymmetrical arrangements found in Ukiyo-e prints can be seen as a parallel to Mankes's own aesthetic sensibilities, especially in his graphic works. His prints, numbering around 50, showcase a remarkable delicacy and an innate understanding of the medium.

The broader European Symbolist movement, with artists like Odilon Redon in France or Fernand Khnopff in Belgium, also provides a context for Mankes's work. While not directly part of any formal group, Mankes shared with the Symbolists an interest in conveying subjective experience, mood, and the unseen spiritual dimensions of reality, rather than a purely objective depiction. His art often evokes a dreamlike, introspective atmosphere akin to some Symbolist painters. Even the tonal subtleties of an artist like James McNeill Whistler, with his emphasis on mood and atmosphere over strict representation, might find a distant echo in Mankes's refined aesthetic.

The Crucial Role of Anne Zernike

A significant turning point in Mankes's personal and, to some extent, intellectual life was his meeting Anne Zernike in 1913. Anne was a remarkable figure in her own right: a theologian and the first woman to be ordained as a minister in the Netherlands (in 1911, within the Mennonite community). Their connection was deep and multifaceted, leading to their marriage in 1915.

Anne Zernike was a woman of considerable intellect and progressive views. She introduced Mankes to a wider world of ideas, engaging him in discussions on philosophy, religion, and science. Through her, Mankes's intellectual horizons expanded, although his art remained deeply rooted in his personal, intuitive response to the world around him. Their relationship, initially viewed with some skepticism by more conservative elements of society due to Anne's unconventional role as a female minister, was one of mutual support and intellectual companionship.

They resided for a time in The Hague, and later, due to Mankes's declining health, moved to Eerbeek in Gelderland, seeking the benefits of cleaner air. Anne's presence provided stability and intellectual stimulation during a period when Mankes was grappling with his art and his health. She was a steadfast companion, and her understanding of his artistic needs was undoubtedly crucial.

Patronage and Artistic Circles

Despite his preference for a somewhat secluded life, Jan Mankes was not entirely isolated from the art world. A key figure in supporting his career was A.A.M. Pauwels, a tobacco merchant and art collector from The Hague. Starting around 1909, Pauwels became Mankes's patron, providing him with a regular income in exchange for his work. Their relationship is documented through an extensive correspondence of nearly 700 letters, offering invaluable insights into Mankes's thoughts, working methods, and daily life. Pauwels not only provided financial support but also supplied Mankes with materials, including books, periodicals, and even animal subjects (both living and deceased) for his paintings.

While Pauwels was a crucial supporter, their relationship was not without its complexities. Pauwels, a conservative Catholic, sometimes expressed concern over Mankes's more liberal intellectual explorations, particularly those influenced by his relationship with Anne Zernike. Nevertheless, Pauwels's sustained patronage was vital, allowing Mankes the freedom to develop his art without the immediate pressure of commercial sales. Mankes did exhibit his work, for instance at the prestigious Pulchri Studio in The Hague, bringing his art to a wider, albeit still select, audience.

Mankes also had connections with other figures in the cultural sphere. He was influenced by the writings of Lodewijk van Deyssel, a prominent literary figure associated with the Tachtigers (the "Eightiers" movement in Dutch literature). Mankes even emulated Van Deyssel's diary-writing style for a time. However, he also critically engaged with Van Deyssel's ideas, particularly on matters of religion, where Mankes leaned towards a more materialist or pantheistic appreciation of beauty in the tangible world. Brief mentions of a more nomadic artistic life with friends Chris Huidekoper and Ditte Lebeu around 1917 suggest periods of shared artistic endeavor, though details are scarce.

Compared to the bustling Amsterdam Impressionists like George Hendrik Breitner or Isaac Israëls, who captured the vibrant city life, Mankes's world was far more insular and focused. His contemporaries also included artists who were pushing towards abstraction, such as Piet Mondrian, who, in his early career, also painted sensitive landscapes before embarking on his neoplasticist journey. Jan Toorop was another significant Dutch contemporary, deeply involved in Symbolism and Art Nouveau, whose intricate lines and mystical themes offer a contrast to Mankes's quieter, more distilled symbolism. Mankes's path remained uniquely his own, focused on an intimate and poetic realism. Another Dutch artist of a slightly older generation, Matthijs Maris, whose work also possessed a dreamy, introspective quality, might be seen as sharing a certain spiritual affinity with Mankes, though their styles differed.

Representative Masterpieces

Jan Mankes produced approximately 200 oil paintings, 100 drawings, and 50 prints in his short career. Several works stand out as quintessential examples of his artistry.

_Owl on a Branch_ (1911): This small oil painting is one of his most iconic images. The owl, rendered with exquisite detail, stares directly at the viewer with an almost hypnotic intensity. The feathers are meticulously painted, yet the overall effect is not one of photographic realism but of heightened presence. The muted background focuses all attention on the bird, which seems to embody a timeless, watchful wisdom.

_Two Mice_ (1916): This work demonstrates Mankes's ability to find significance and beauty in the most humble subjects. The two small mice are depicted with incredible delicacy and sympathy. The soft fur, the alert ears, the tiny paws – all are rendered with a loving attention to detail. The composition is simple, yet the painting exudes a quiet charm and a profound respect for life in all its forms.

_Self-Portrait_ (1915): Mankes painted several self-portraits, each offering a glimpse into his introspective nature. In this particular work, he presents himself with a direct, searching gaze. The features are finely modeled, and the use of light and shadow creates a sense of quiet contemplation. It is the portrait of an artist deeply engaged with his inner world and his perception of reality.

_Crow Looking up at a Mosquito_ (Print): This print showcases his skill in graphic media and his subtle humor. The composition is elegant, capturing a fleeting moment in nature with characteristic precision and a touch of whimsy. His prints often explored the lives of animals in their natural habitats with a poetic sensibility.

These works, and many others, share a common thread: a deep reverence for the subject, a meticulous yet sensitive technique, and an ability to evoke a profound sense of stillness and contemplation.

The Final Years and Enduring Legacy

From 1916 onwards, Jan Mankes's health began to deteriorate due to tuberculosis, a widespread and often fatal disease at the time. Despite his illness, he continued to work, driven by his artistic passion. His wife, Anne Zernike, provided devoted care during these difficult years. They moved to Eerbeek in the hope that the country air would be beneficial, but his condition worsened.

Jan Mankes passed away on April 23, 1920, in Eerbeek, at the tragically young age of 30. His death cut short a career that, while brief, had already produced a body of work remarkable for its maturity, consistency, and unique vision.

Despite his short life and relatively small oeuvre, Jan Mankes's art has endured. His work is held in high esteem in the Netherlands and is increasingly recognized internationally. Major collections of his art can be found in Dutch museums such as Museum MORE in Gorssel (which houses a significant part of the former Scheringa collection), the Museum Belvédère in Heerenveen (Friesland, a region close to his heart), and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

His appeal lies in the timeless, universal qualities of his art: its quiet beauty, its profound empathy for the natural world, and its ability to evoke a sense of peace and contemplation. In a world often characterized by noise and haste, Mankes's paintings offer a sanctuary of stillness, inviting viewers to pause and appreciate the delicate wonders of existence. He remains a testament to the power of an artist who, by looking closely and lovingly at the world around him, created art of enduring spiritual depth. His legacy is that of a painter of the soul, whose ethereal visions continue to touch and inspire.