Edward Collier, also known during his lifetime as Edwaert Colyer or Kollier, stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Active during the latter half of the 17th and early 18th centuries, Collier carved a niche for himself primarily as a painter of still lifes, excelling in the symbolic vanitas genre and the illusionistic trompe-l'oeil technique. His life and career bridged the vibrant art scenes of the Netherlands and England, leaving behind a body of work admired for its technical skill, intricate detail, and contemplative depth.

Origins and Early Artistic Formation

Born around 1640 in Breda, located in the province of North Brabant in the Dutch Republic, Edward Collier's early life and artistic training are not exhaustively documented. However, art historians generally concur that his formative years as a painter likely took place in Haarlem. This city was a powerhouse of still-life painting during the Golden Age, home to influential masters whose work emphasized realism and subtle composition.

The stylistic characteristics of Collier's earlier works strongly suggest an absorption of the Haarlem tradition. Influences from prominent Haarlem still-life painters such as Pieter Claesz and Willem Claesz. Heda are often noted. These artists were renowned for their 'ontbijtjes' (breakfast pieces) and monochrome banquet scenes, characterized by carefully arranged objects, subdued palettes, and masterful rendering of textures. It's possible Collier also absorbed lessons from artists like Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne, another Haarlem painter known for vanitas themes. The Haarlem school's focus on tangible reality and symbolic meaning undoubtedly shaped Collier's artistic foundations.

The Leiden Period and Guild Membership

By 1667, Edward Collier had relocated to Leiden, another major artistic and intellectual center in the Netherlands. Leiden was particularly famous for its university and for fostering the 'fijnschilder' tradition – painters known for their exceptionally fine, detailed, and highly polished technique. Artists like Gerard Dou, a pupil of Rembrandt, and Frans van Mieris the Elder were leading exponents of this meticulous style in Leiden.

Collier's presence in Leiden is firmly established by his membership in the city's Guild of Saint Luke, which he joined in 1673. Membership in the guild was essential for artists wishing to practice professionally, take on pupils, or sell their work within the city. His acceptance into the Leiden guild signifies his recognition as a competent professional painter. His time in Leiden likely further honed his skills in detailed representation, a hallmark that would remain consistent throughout his career, particularly evident in his depictions of books, scientific instruments, and other objects requiring precise rendering.

Amsterdam and Continued Development

Following his productive period in Leiden, Collier moved again, this time to the bustling metropolis of Amsterdam, around 1680. Amsterdam was the commercial and artistic heart of the Dutch Republic, offering unparalleled opportunities and patronage. While specific details of his activities in Amsterdam are scarce, this move placed him in the orbit of other major artistic currents.

Amsterdam was home to diverse talents, from the towering figure of Rembrandt (though Rembrandt himself had passed away in 1669, his influence lingered) to sophisticated still-life painters like Willem Kalf, known for his opulent 'pronkstilleven' (ostentatious still lifes). While Collier largely maintained his focus on vanitas and, increasingly, trompe-l'oeil compositions, the dynamic environment of Amsterdam may have broadened his artistic horizons or exposed him to different market demands before his eventual move across the North Sea.

Relocation to London: A New Chapter

A significant shift in Collier's life and career occurred in 1693 when he moved to London. This move marks a period where his work gained a distinct character, often incorporating English elements and catering perhaps to a different clientele. The reasons for his relocation are not definitively known but could relate to patronage opportunities or the changing economic climate in the Netherlands following the 'Rampjaar' (Disaster Year) of 1672 and subsequent conflicts.

His arrival in London coincided with a period when Dutch and Flemish artists were finding considerable success in England. Portraitists like Sir Peter Lely (originally from Westphalia but trained in Haarlem) and Sir Godfrey Kneller (from Lübeck, also Dutch-influenced) dominated the court scene. While Collier worked in a different genre, his presence contributed to the influx of Netherlandish artistic skill into England. It was during his London years that Collier produced many of his most famous trompe-l'oeil works, particularly the 'letter rack' or 'quodlibet' paintings.

The Art of Vanitas: Contemplating Mortality

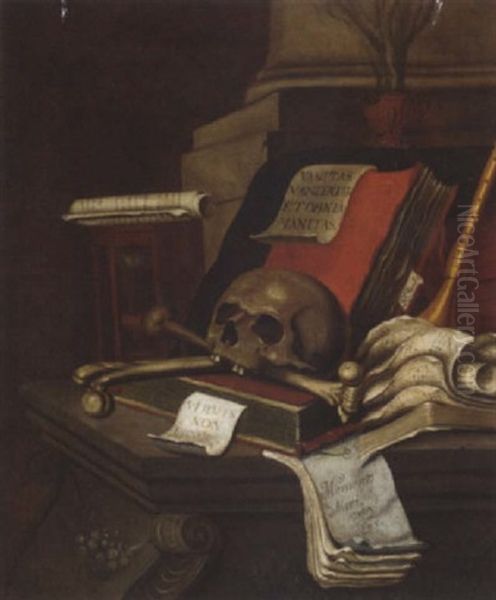

Edward Collier is perhaps most strongly associated with the vanitas still life, a genre deeply rooted in the Calvinist culture of the Dutch Republic. Vanitas paintings served as moral allegories, reminding viewers of the transience of earthly life, the futility of worldly pursuits, and the inevitability of death. Collier masterfully employed a repertoire of symbols to convey these messages.

Skulls are the most direct symbol of death (memento mori). Timepieces, such as hourglasses or pocket watches, signify the relentless passage of time and the brevity of human existence. Snuffed-out candles or oil lamps represent life extinguished. Musical instruments (lutes, violins, flutes) and sheet music often symbolize the fleeting nature of sensual pleasures. Books, globes, and scientific instruments might represent the limits of human knowledge and worldly achievements in the face of eternity. Luxury items like jewelry, coins, and fine fabrics point to the vanity of wealth and earthly possessions. Soap bubbles, ephemeral and easily burst, were another common motif for life's fragility.

A prime example of Collier's work in this genre is Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s Emblemes (1696), now in the Tate collection, London. This painting meticulously arranges symbolic objects: a skull rests prominently, a watch lies nearby, musical instruments suggest transient joys, and an open book displays George Wither's emblems, reinforcing the moral message. Often, Collier included inscriptions, such as quotes from the Book of Ecclesiastes ("Vanity of vanities; all is vanity"), to make the theme explicit. His Still Life with Books and Manuscripts and a Skull (1663) shows his early engagement with these themes, demonstrating technical skill even as a younger artist. His approach aligns with other vanitas specialists like David Bailly (also active in Leiden) and Harmen Steenwijck.

Mastery of Trompe-l'oeil: Deceiving the Eye

While continuing to paint vanitas themes, Collier increasingly explored trompe-l'oeil ('deceive the eye') painting, especially during his London period. This technique aimed to create such convincing illusions of reality that viewers might momentarily mistake the painted objects for real ones. Collier specialized in 'letter rack' paintings, compositions depicting a collection of papers, letters, ribbons, and small objects seemingly tacked or tucked into straps on a wooden board.

These works showcased Collier's exceptional skill in rendering different textures – the crispness of paper, the sheen of silk ribbons, the grain of wood, the metallic glint of a key or seal. The objects depicted often included contemporary newspapers (like the London Gazette), almanacs, letters with legible addresses or seals, quill pens, combs, and sometimes medals or prints. This choice of subject matter has led some scholars to interpret these works as subtle commentaries on the burgeoning 'media revolution' of the late 17th century, reflecting a world increasingly saturated with printed information and correspondence.

The appeal of trompe-l'oeil lay in its cleverness and the artist's virtuosity. It was a visual game played with the viewer, demonstrating the power of painting to mimic reality. Collier's work in this area can be compared to that of other Dutch masters of illusionism, such as Samuel van Hoogstraten, who famously painted perspective boxes and trompe-l'oeil still lifes earlier in the century. Collier's letter racks, however, became a signature style, often signed and dated, providing valuable documentation of his output.

Technical Skill and Artistic Signature

Throughout his career, regardless of the specific subgenre, Collier's work was characterized by meticulous attention to detail and a high degree of finish. This aligns with the Leiden 'fijnschilder' aesthetic, even in works produced long after he left that city. He demonstrated a keen ability to render the specific textures and surfaces of diverse objects – the brittle pages of old books, the reflective curve of a glass sphere, the intricate patterns on a tapestry, the cold hardness of a skull.

His compositions are typically carefully balanced, often arranging objects on a draped table or within the shallow space of a letter rack. His use of light and shadow is effective in modeling forms and creating a sense of depth, though perhaps less dramatic than the chiaroscuro employed by artists like Rembrandt. The overall impression is one of clarity, precision, and thoughtful arrangement, inviting close inspection by the viewer.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

While direct records of collaboration or close personal friendships between Edward Collier and other specific painters are lacking, his career unfolded within a vibrant and interconnected art world. In Haarlem, he was preceded and influenced by the foundational still-life work of Pieter Claesz and Willem Claesz. Heda. In Leiden, he worked alongside artists steeped in the 'fijnschilder' tradition like Gerard Dou and Frans van Mieris the Elder, and within the vanitas tradition associated with David Bailly and Pieter Potter.

His time in Amsterdam placed him in the largest art market of the era, where the legacy of Rembrandt loomed large and where contemporaries like Willem Kalf set standards for opulent still life, and artists like Rachel Ruysch excelled in detailed flower painting. In London, he joined a growing community of continental artists, including the dominant portraitists Lely and Kneller, contributing his specific Dutch skills to the English scene. His work, particularly the trompe-l'oeil letter racks, found a receptive audience in England.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Edward Collier's influence extended through both the Dutch and English art traditions. He was a significant practitioner of the vanitas genre, contributing numerous thoughtful and skillfully executed examples that perpetuated its moralizing themes. His mastery of trompe-l'oeil, particularly the letter rack format, represents a distinct contribution to still-life painting, showcasing illusionistic techniques while also capturing aspects of contemporary material culture.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, Collier's dedication to craftsmanship and his ability to imbue still-life objects with symbolic weight ensured his reputation. His works influenced subsequent still-life painters in both the Netherlands and England who continued to explore vanitas themes and illusionistic techniques into the 18th century. Today, his paintings are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Tate Britain in London, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Denver Art Museum, appreciated for their technical finesse and as windows into the visual and intellectual culture of the Dutch Golden Age and early Georgian England.

Final Years

Sources suggest that Collier may have briefly returned to Leiden between 1702 and 1706, possibly maintaining connections with his former home city. However, his death is recorded in London. Edward Collier passed away in London and was buried on September 8, 1708, at St James's Church, Piccadilly. His life spanned a period of immense artistic creativity and cultural exchange, and his work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of still-life painting and its capacity for both visual delight and profound reflection. He leaves behind a legacy as a skilled practitioner who navigated the artistic currents of his time, mastering genres that captured the fascination with realism, illusion, and the contemplation of life's transient nature.