Introduction: A Golden Age Painter

Pieter Claesz. stands as one of the most significant and influential still life painters of the Dutch Golden Age, a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing in the Netherlands during the 17th century. Active primarily in the vibrant artistic center of Haarlem, Claesz. specialized in still life compositions that captured the textures, forms, and subtle interplay of light on everyday objects. He is particularly renowned for his mastery of the "monochrome" or tonal still life, especially the popular genres of the ontbijtje (breakfast piece) and the vanitas. His work, characterized by its subdued palettes, atmospheric depth, and profound symbolism, offers a quiet yet compelling meditation on the nature of material existence and the passage of time.

Born around 1597 or 1598, likely in Berchem near Antwerp in present-day Belgium, Claesz. moved to Haarlem, where he established his career and became a leading figure in the local Guild of Saint Luke. Working alongside contemporaries who excelled in various genres – from the dramatic portraits of Frans Hals to the evocative landscapes of Jacob van Ruisdael – Claesz. carved a distinct niche for himself, refining still life painting into a sophisticated art form capable of conveying complex ideas through simple arrangements. His legacy endures not only in the beauty and technical brilliance of his paintings but also in his influence on subsequent generations of still life artists.

Early Life and Relocation to Haarlem

Details about Pieter Claesz.'s earliest years and artistic training remain somewhat scarce, a common situation for many artists of this period. It is generally accepted that he was born in Berchem, a village near the major artistic hub of Antwerp, around 1597/1598. Antwerp was a center for lavish Baroque still life, exemplified by artists like Frans Snyders, and it is possible Claesz. received some initial exposure to this tradition, though his mature style would diverge significantly.

The pivotal move in his early life was his relocation to Haarlem, a prosperous city in the Dutch Republic that was rapidly becoming a major center for painting, particularly still life and landscape. The exact date of his move is uncertain, but records indicate he married in Haarlem in 1617. By 1620 or 1621, he was likely active as a painter and soon became a member of the Haarlem Guild of Saint Luke, the professional organization for artists and artisans. Membership in the guild was crucial for establishing a workshop, taking on apprentices, and selling work legally. Claesz. would remain in Haarlem for the rest of his life, passing away there and being buried on January 1, 1661.

His decision to settle in Haarlem placed him at the heart of innovative developments in Dutch art. The city fostered a climate where artists specialized, responding to the demands of a growing middle-class market eager for secular art forms to decorate their homes. Claesz.'s focus on still life perfectly suited this environment.

The Artistic Milieu of Haarlem

Haarlem in the first half of the 17th century was a crucible of artistic innovation. Alongside Amsterdam and Utrecht, it was one of the leading centers of painting in the Dutch Republic. The city boasted a thriving economy, fueled by brewing, textiles, and trade, which supported a substantial population of potential art patrons. Unlike the predominantly Catholic South (Flanders), the Calvinist North had less demand for large-scale religious altarpieces, leading artists to specialize in genres like portraiture, landscape, genre scenes (depictions of everyday life), and still life.

The Haarlem Guild of Saint Luke played a vital role in regulating the art trade and maintaining standards. Claesz.'s membership signifies his professional standing. He worked within a community of highly skilled painters. Frans Hals was the city's dominant portrait painter, known for his lively brushwork. Landscape specialists like Jacob van Ruisdael and Salomon van Ruysdael captured the Dutch countryside. Genre painters such as Adriaen Brouwer (though Flemish, worked in Haarlem for a time) and later Judith Leyster depicted scenes of peasant life or domestic interiors.

Within this diverse scene, Haarlem became particularly renowned for still life painting. Claesz., along with his contemporary Willem Claesz. Heda, became the leading exponents of a specific type of still life – the tonal or monochrome style – which became characteristic of the Haarlem school in the 1620s and 1630s. This shared environment likely fostered both competition and mutual influence among artists.

Artistic Development: From Early Vibrancy to Tonal Subtlety

Pieter Claesz.'s artistic style evolved significantly throughout his career. His earliest known works, dating from the early 1620s, show some connection to broader European trends but quickly establish his focus on still life. An early example, Still Life with Musical Instruments (1623), displays a relatively rich palette compared to his later work, though already demonstrating his skill in rendering different textures and arranging objects in a seemingly casual yet carefully constructed composition.

These initial works often featured a somewhat higher viewpoint and a clearer, more evenly distributed light than his mature style. The objects depicted might include musical instruments, books, and tableware, sometimes hinting at the Vanitas themes that would become more prominent later. The colors, while not as opulent as contemporary Flemish works, were more varied than the near-monochrome palettes he would soon adopt.

The crucial shift occurred around the mid-1620s. Claesz., alongside Willem Claesz. Heda, began to explore the possibilities of a severely restricted palette, focusing on subtle gradations of browns, grays, greens, and ochres. This move towards tonalism marked a departure from the brighter colors seen in earlier Dutch still life and the richness of Antwerp painters. It allowed Claesz. to concentrate on the effects of light, atmosphere, and texture, creating compositions of remarkable harmony and quiet intensity.

The Rise of the Monochrome Still Life: Ontbijtjes

The development of the tonal or monochrome style is inextricably linked with the popularity of the ontbijtje, or breakfast piece (though the term could also refer to any simple meal). These paintings typically depict the remnants of a modest meal laid out on a table: perhaps a bread roll, a piece of cheese, some nuts or fruit, a herring on a pewter plate, a knife, and glassware like a Roemer (a green-tinted wine glass with a studded base) or a tall Berkemeyer.

Claesz. became a master of this genre. His breakfast pieces from the late 1620s and 1630s exemplify the monochrome approach. He used a limited range of colors, primarily earth tones, to unify the composition. The viewpoint is often lowered, bringing the viewer closer to the table surface. Light typically enters from one side, usually the left, casting soft shadows and creating subtle highlights on the different surfaces – the rough crust of the bread, the dull sheen of pewter, the glint of light on a glass rim, the sharp edge of a knife.

These works, such as his numerous Breakfast Pieces from this period, are celebrated for their simplicity and realism. The arrangements often appear informal, with objects overlapping and sometimes placed precariously close to the table edge, adding a sense of immediacy. Despite their apparent modesty, these paintings were highly sophisticated exercises in composition, light, and texture, appealing to the Dutch appreciation for understated craftsmanship and the beauty found in everyday life.

Mastery of Light, Texture, and Reflection

A defining characteristic of Pieter Claesz.'s art is his extraordinary ability to render light and texture. His adoption of a tonal palette allowed him to focus intensely on how light interacts with different surfaces. He masterfully captured the cool, matte surface of pewter plates, often showing slight dents or scratches that enhance their realism. Glassware, particularly the characteristic Roemers, provided opportunities to depict transparency, refraction, and complex reflections of nearby objects and the unseen window.

Claesz. paid meticulous attention to the specific textures of food items. The crumbly interior and crisp crust of a broken bread roll, the oily sheen of a herring, the delicate skin of a half-peeled lemon (a recurring motif, adding a touch of brighter color and signifying luxury or temperance), or the rough shell of a walnut are all rendered with convincing tactility. He often contrasted these textures within a single composition – the smooth glass against rough bread, the hard pewter against soft fabric (like a crumpled napkin).

His handling of light is subtle yet dramatic. He favored a diagonal shaft of light entering from the side, illuminating parts of the composition while leaving other areas in soft shadow. This use of chiaroscuro creates a sense of depth and volume, making the objects feel tangible and present within a defined space. Reflections, whether on a polished knife blade, a silver beaker, or the surface of wine in a glass, add complexity and further enhance the illusion of reality. This technical virtuosity was central to the appeal of his work.

Iconography and Symbolism: The Vanitas Still Life

Beyond the breakfast pieces, Pieter Claesz. was a leading practitioner of the vanitas still life, a genre deeply imbued with symbolic meaning. Vanitas paintings served as moral reminders of the transience of life, the futility of earthly pleasures, and the certainty of death. These themes resonated strongly within the Calvinist culture of the Dutch Republic, which emphasized piety and reflection on mortality.

Claesz.'s vanitas works employ a specific repertoire of symbols. The human skull is the most direct emblem of death (memento mori – "remember you must die"). Other common symbols include:

Timepieces (watches, hourglasses): Representing the relentless passage of time.

Snuffed or guttering candles: Symbolizing life extinguished or fading.

Books and writing implements (like quills): Indicating the limits of human knowledge and earthly pursuits.

Musical instruments and sheet music: Often signifying the fleeting nature of sensual pleasures.

Overturned or empty glasses, pipes, playing cards: Representing transient or sinful pleasures.

Wilting flowers or decaying fruit: Showing the inevitability of decay.

Soap bubbles: Embodying the fragility and brevity of life (homo bulla – "man is a bubble").

Mirrors or glass spheres: Reflecting the world but also symbolizing vanity or illusion.

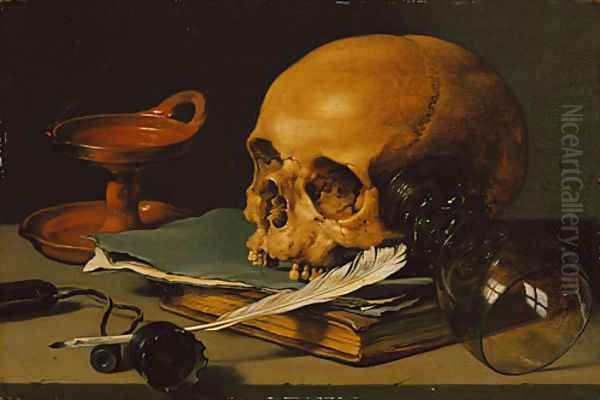

A prime example is his Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill (1628). Here, the skull dominates, placed alongside an overturned Roemer, an expired oil lamp, and writing materials. The composition is stark, rendered in Claesz.'s characteristic tonal palette, emphasizing the somber message. The careful arrangement and realistic rendering give these symbolic objects a powerful presence, prompting contemplation in the viewer. Another well-known work, Vanitas with Violin and Glass Ball, incorporates musical elements alongside the skull and timepiece.

Iconography in the Ontbijtjes

While less overtly didactic than the vanitas paintings, Claesz.'s breakfast pieces also carry potential layers of meaning beyond the simple depiction of food and tableware. The choice of objects, though seemingly everyday, could subtly allude to contemporary Dutch values and concerns.

The very simplicity of the meal often depicted – bread, herring, cheese, beer – could be seen as reflecting ideals of moderation and thrift, important virtues in Calvinist society. However, elements like imported lemons, expensive glassware, or silver objects hinted at the growing prosperity of the Dutch Republic and the availability of luxury goods through international trade. The presence of these items might serve as a quiet reminder of wealth, but perhaps also of its potential dangers or fleeting nature, subtly linking the ontbijtje to vanitas themes.

The act of depiction itself, the meticulous rendering of humble objects, can be interpreted as finding beauty and significance in the everyday, a common thread in Dutch Golden Age art. Some scholars also suggest possible Eucharistic undertones in the depiction of bread and wine, although overt religious symbolism is generally restrained in Claesz.'s work compared to earlier traditions. Ultimately, the breakfast pieces operate on multiple levels: as stunning displays of technical skill, realistic portrayals of daily life, and subtle meditations on material existence.

Analysis of Key Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of Pieter Claesz.'s style and thematic concerns:

Still Life with Skull and Writing Quill (1628, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): This is a quintessential vanitas. The stark composition centers on the skull, quill, expired lamp, and overturned glass. Rendered in a restricted palette of browns and grays, the painting powerfully conveys the themes of mortality and the vanity of human endeavors like learning (quill and book). The lighting is dramatic, highlighting the skull's form while casting deep shadows, creating a somber, contemplative mood. The realism of the objects makes the symbolic message all the more potent.

Breakfast Piece with Berkemeyer (c. 1630s, various versions exist): Many paintings fit this description, showcasing Claesz.'s mastery of the ontbijtje. Typically, such works feature a simple meal on a white tablecloth partially covering a wooden table. Objects like a pewter plate with a half-eaten bread roll, a knife angled towards the viewer, nuts scattered nearby, and a prominent Berkemeyer or Roemer glass filled with wine or beer are common. The composition often uses diagonals (the knife, the folds of the cloth) to create dynamism within the stable arrangement. The focus is on the interplay of light and texture across these humble items, rendered in subtle tonal variations.

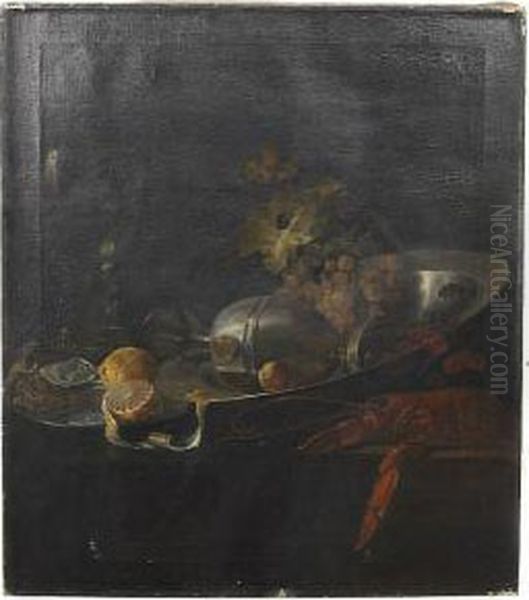

Still Life with Turkey Pie (1627, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): This slightly earlier work shows a more elaborate and colorful display than the typical monochrome breakfast pieces, perhaps indicating a transition or a response to a specific commission. The large, ornate turkey pie dominates the composition, surrounded by olives, lemons, bread, a silver salt cellar, and various drinking vessels. While still demonstrating Claesz.'s skill with texture and light, the richer array of objects and slightly brighter palette point towards influences from more opulent still life traditions, though handled with his characteristic restraint and focus on realism.

Vanitas Still Life with Spinario (1628, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): This intriguing vanitas includes a plaster cast of the famous Hellenistic sculpture, the Spinario (Boy with Thorn), alongside the usual symbols of mortality like a skull, an extinguished candle, and books. The inclusion of the sculpture adds another layer, perhaps commenting on the vanity of art and classical learning in the face of death, or contrasting enduring art with transient life. The complex interplay of objects and their symbolic resonances is typical of Claesz.'s intellectual depth.

Later Career and Stylistic Evolution

From the 1640s onwards, Pieter Claesz.'s style underwent further, albeit subtle, evolution. While he continued to produce works in the tonal style that had brought him fame, some of his later paintings show a move towards slightly richer palettes and more elaborate compositions. This may reflect broader trends in Dutch still life, possibly influenced by artists in Amsterdam like Jan Davidsz. de Heem, who favored more opulent displays (pronkstilleven).

In some later works, Claesz. incorporated more luxurious items, such as silver jugs, elaborate nautilus cups, or more abundant displays of fruit. The arrangements could become more complex, sometimes featuring objects piled higher or spread more widely across the canvas. The lighting might become slightly softer or more diffused compared to the starker contrasts of his earlier vanitas pieces.

However, even in these richer compositions, Claesz. generally retained his fundamental interest in realistic texture, the subtle play of light, and a sense of balanced, harmonious arrangement. He never fully embraced the overt lavishness of the Flemish Baroque or the later Dutch pronkstilleven. His work always maintained a certain sobriety and focus on the tangible quality of the objects depicted. His son, Nicolaes Pieterszoon Berchem, born in 1620, became a famous painter in his own right, but specialized in Italianate landscapes, diverging significantly from his father's focus.

Influence and Legacy

Pieter Claesz., along with Willem Claesz. Heda, firmly established the monochrome breakfast piece and the Haarlem style of vanitas painting. Their work set a standard for technical excellence and subtle composition that influenced many other artists in Haarlem and beyond. While direct pupils are not extensively documented besides his son (who chose a different path), his impact can be seen in the numerous still lifes produced in Haarlem throughout the mid-17th century that adopted similar palettes, subjects, and compositional strategies.

His paintings were clearly popular with Dutch collectors during his lifetime and have remained highly esteemed ever since. Today, his works are held in major museums across the world, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Claesz.'s enduring appeal lies in his ability to elevate humble, everyday objects into subjects of profound artistic contemplation. His technical mastery in rendering light and texture remains astonishing, while the quiet symbolism embedded in his works continues to invite interpretation. He represents a key aspect of the Dutch Golden Age: the capacity to find beauty, meaning, and artistic sophistication in the careful observation of the material world.

Claesz. and His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Pieter Claesz.'s contribution, it is helpful to place him within the broader context of the Dutch Golden Age art scene. He was working during a period of incredible artistic output across various genres:

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669): Based primarily in Amsterdam, Rembrandt was the towering figure of the era, renowned for his psychologically penetrating portraits, dramatic history paintings, and innovative etchings.

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675): Working in Delft, Vermeer created intimate genre scenes celebrated for their exquisite handling of light, color, and serene atmosphere.

Frans Hals (c. 1582-1666): The leading portraitist in Haarlem during Claesz.'s time, known for his dynamic brushwork and ability to capture the sitter's vitality.

Jan Steen (c. 1626-1679): Famous for his lively, often humorous, and morally instructive genre scenes depicting Dutch domestic life and taverns.

Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1628-1682): Also active in Haarlem, he was the preeminent landscape painter of the Dutch Golden Age, known for his dramatic and evocative depictions of nature.

Willem Claesz. Heda (1594-c. 1680): Claesz.'s closest counterpart in Haarlem, also specializing in monochrome still lifes, often with slightly cooler palettes and perhaps more emphasis on elegant arrangements compared to Claesz.'s sometimes more robust textures.

Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684): Initially working in Leiden and later Antwerp, De Heem became famous for more elaborate and colorful still lifes, including fruit and flower pieces, influencing the later trend towards pronkstilleven.

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750): A later, highly successful female artist specializing in detailed and dynamic flower still lifes.

Judith Leyster (1609-1660): One of the few recognized female painters of the era, active in Haarlem, known for genre scenes and portraits, sometimes compared to Hals.

Adriaen Brouwer (1605-1638): A Flemish painter who worked for a time in Haarlem, influential for his expressive depictions of peasant life.

Gerard ter Borch (1617-1681): Known for his refined genre scenes depicting elegant interiors and interactions among the upper classes, noted for his exquisite rendering of fabrics like satin.

Albert Cuyp (1620-1691): Famous for his idyllic landscapes, often bathed in a golden Italianate light, featuring cattle and river scenes near Dordrecht.

Paulus Potter (1625-1654): Specialized in paintings of animals, particularly cattle, depicted with remarkable realism within Dutch landscapes.

Compared to these contemporaries, Claesz.'s focus was narrower but pursued with exceptional depth and consistency. His dedication to the still life genre, particularly the tonal style, allowed him to explore the nuances of perception, representation, and meaning within carefully controlled compositions.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Pieter Claesz. remains a pivotal figure in the history of still life painting and a standout artist of the Dutch Golden Age. His move from the environs of Antwerp to the dynamic artistic center of Haarlem set the stage for a career dedicated to the meticulous observation and representation of the material world. As a pioneer and master of the monochrome or tonal still life, he developed a distinctive style characterized by subdued palettes, subtle lighting, convincing textures, and balanced compositions.

Through his popular ontbijtjes and profound vanitas paintings, Claesz. did more than just record the appearance of everyday objects. He imbued them with atmosphere and potential meaning, prompting reflections on consumption, domesticity, luxury, the passage of time, and the nature of mortality. His technical brilliance in capturing the play of light on diverse surfaces – glass, pewter, bread, fruit – continues to captivate viewers.

Working alongside giants like Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Hals, Pieter Claesz. demonstrated the power and sophistication that the seemingly humble genre of still life could achieve. His works offer a quiet counterpoint to the drama of history painting or the dynamism of portraiture, inviting close looking and contemplation. His legacy lies not only in his beautiful and enduring paintings found in collections worldwide but also in his crucial role in shaping the course of still life painting in the Netherlands and beyond.