Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten stands as a significant figure in the art history of the Dutch Golden Age, bridging the artistic traditions of the Netherlands with the burgeoning art market of Restoration England. Born in Haarlem and trained by one of the era's giants, Frans Hals, Van Roestraten carved out a distinct niche for himself, primarily as a master of the still life genre, particularly renowned for his depictions of silverware and Vanitas themes. His move to London marked a pivotal point in his career, where he found considerable success and patronage, leaving behind a body of work admired for its technical brilliance and symbolic depth.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Haarlem

Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten entered the world in Haarlem, a vibrant center of Dutch art, on April 21, 1630. His artistic journey began formally in 1646 when he embarked on an apprenticeship under the tutelage of the celebrated portraitist Frans Hals. This was a prestigious start, placing him within the workshop of one of the most dynamic and influential painters of the time. Hals's mastery of capturing likeness and character, often with a remarkably fluid and energetic brushstroke, would undoubtedly have provided a foundational, if contrasting, influence on the young Van Roestraten's developing style.

Also in 1646, Van Roestraten registered with the Haarlem Guild of Saint Luke. Membership in the guild was essential for practicing artists, signifying professional recognition and adherence to the standards of the craft. He continued his training within Hals's circle, likely absorbing not only technical skills but also insights into the business of art and portraiture. His formal training under Hals is documented as lasting until around 1651, equipping him with the skills necessary to launch his own career.

A significant personal and professional connection was forged in 1654 when Van Roestraten married Adriaentje Hals, the daughter of his master, Frans Hals. This union further cemented his ties to the esteemed Hals family and the Haarlem artistic community. While Adriaentje is sometimes mentioned in relation to the Hals artistic legacy, her own output as a painter is less documented compared to her father or husband. Nevertheless, this marriage placed Van Roestraten firmly within a prominent artistic dynasty.

Transition and Relocation to London

Following his marriage, Van Roestraten continued to work as an artist, likely dividing his time between Haarlem and possibly Amsterdam, another major Dutch artistic hub. During this period, he would have been active primarily as a portrait painter, following in the footsteps of his famous father-in-law. The Dutch art market was highly developed, but also competitive, with numerous talented painters vying for commissions.

A major shift occurred in Van Roestraten's life and career between 1663 and 1665 when he made the decision to relocate to London. The reasons for this move are not explicitly detailed but likely involved seeking new opportunities and patronage. Restoration London, following the return of King Charles II, was experiencing a cultural revival and offered potential for artists, particularly those with skills honed in the sophisticated Dutch market. Several Dutch and Flemish artists found success in England during this period.

This move marked a significant turning point. While initially trained in portraiture, Van Roestraten increasingly turned his attention to still life painting after arriving in England. This shift in focus proved highly successful.

Success and Recognition in England

Van Roestraten's arrival in London coincided with a growing appetite among the English aristocracy for luxury goods and the art that depicted them. His particular skill in rendering opulent objects, especially silver, resonated well with the tastes of the time. His still life paintings quickly gained favour, reportedly catching the attention of King Charles II himself. As a mark of royal appreciation for his work, he is said to have received a royal medal, a significant honour that would have boosted his reputation considerably.

One anecdote, recounted by early art biographers, suggests that the prominent court painter Sir Peter Lely played a role in Van Roestraten's career trajectory. Lely, a dominant figure in English portraiture alongside Sir Godfrey Kneller later on, allegedly advised Van Roestraten to focus on still life rather than compete in the potentially crowded field of portraiture. Whether this advice was the primary catalyst or simply confirmed a direction Van Roestraten was already taking, the shift proved astute.

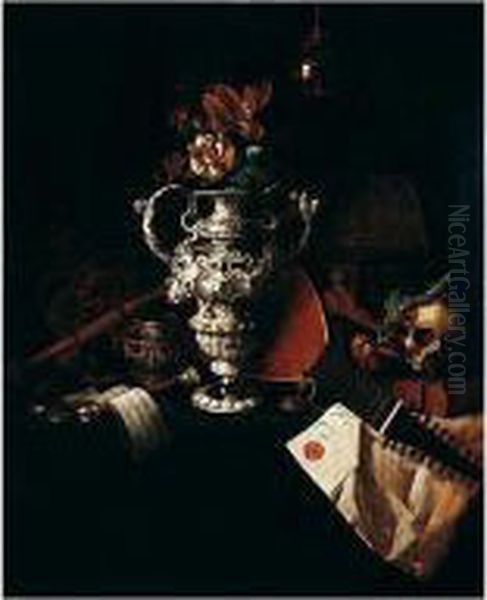

His still life paintings, particularly those known as 'pronkstilleven' or ostentatious still lifes, became highly sought after. These works often featured elaborate arrangements of valuable items – gleaming silver vessels, imported Chinese porcelain, reflective glassware, rich textiles, and sometimes musical instruments or scientific objects. His ability to capture the textures and reflective qualities of these materials was exceptional.

The demand for his work was substantial, and his paintings commanded high prices. This success enabled Van Roestraten to establish a comfortable life and career in London, where he remained active for over three decades, a testament to his enduring appeal to English collectors. While he may not have achieved the absolute fame of court portraitists like Lely or Kneller, he occupied a respected and profitable niche within the London art world.

Artistic Style: The Pronkstilleven and Vanitas

Van Roestraten's mature style is most closely associated with the still life genre, specifically the 'pronkstilleven' and the Vanitas theme. The pronkstilleven, a type of elaborate still life that became popular in the Netherlands and Flanders, aimed to display abundance and luxury. Artists like Willem Kalf were masters of this genre in the Netherlands, creating sumptuous compositions. Van Roestraten adapted this tradition for the English market, often focusing intensely on the depiction of silver.

His paintings frequently showcase intricately crafted silver items: tankards, goblets, salvers, candlesticks, and snuff boxes, often arranged on richly draped tables. He rendered the cool, reflective surfaces of silver with meticulous detail, capturing the play of light and the distorted reflections of nearby objects, including, occasionally, a subtle self-portrait of the artist at his easel. This focus on silverware became a hallmark of his work.

Beyond mere display, Van Roestraten imbued many of his still lifes with Vanitas symbolism. The Vanitas tradition, deeply rooted in Dutch 17th-century culture, used arrangements of objects to convey moral messages about the transience of life, the futility of earthly pleasures, and the inevitability of death. These were not just displays of wealth, but also reminders of its impermanence.

Common Vanitas symbols found in his work include skulls (the most direct symbol of death), timepieces like pocket watches (representing the passage of time), extinguished or smoking candles (symbolizing life's brevity), flowers (especially those past their prime, indicating beauty's decay), soap bubbles (fragility), musical instruments (fleeting pleasures), and books or globes (the limits of worldly knowledge). By juxtaposing luxurious items with these symbols, Van Roestraten created a tension between material wealth and spiritual contemplation.

Technical Mastery and Composition

Van Roestraten's technical skill was considerable. His training under Frans Hals provided a strong foundation, but his approach in still life was generally tighter and more detailed than Hals's famously loose brushwork in portraiture. He excelled in rendering textures – the hard gleam of silver, the smooth glaze of porcelain, the soft pile of velvet, the crispness of paper.

His use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) was often dramatic, highlighting the key objects against darker, more subdued backgrounds. This technique enhanced the three-dimensionality of the objects and created a focused, often intimate atmosphere. Light reflecting off polished silver or catching the edge of a glass was rendered with particular virtuosity.

Compositionally, his works are typically carefully arranged, though sometimes with a deliberate sense of slight disorder ('georganiseerde wanorde') characteristic of the genre, suggesting recent use or interruption. Objects overlap, creating depth, and diagonals often lead the viewer's eye through the arrangement. The scale was generally suited for domestic interiors, reinforcing their role as objects of private contemplation and display for discerning collectors.

Genre Paintings and Social Commentary

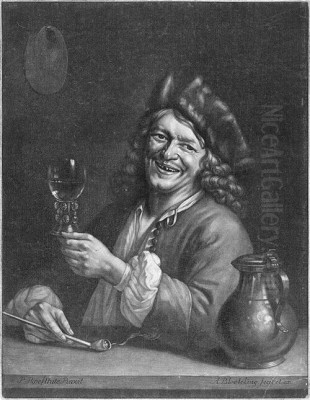

While best known for still lifes, Van Roestraten also produced genre paintings – scenes of everyday life. These works often carry moralizing undertones, similar to his Vanitas still lifes. A notable example is The Licentious Kitchen Maid (c. 1665). Such paintings depicted scenes that could be interpreted as warnings against vice or commentary on social norms and human behaviour.

In The Licentious Kitchen Maid, the depiction likely engages with contemporary attitudes towards domestic servants, temptation, and morality. Genre painting was a major field in the Dutch Golden Age, with artists like Jan Steen being famous for their lively and often humorous or satirical scenes. Van Roestraten's contributions to this genre, while less numerous than his still lifes, show his versatility and engagement with the broader artistic currents of his time.

Incorporation of Exotic Goods: Chinese Porcelain

Reflecting the global trade networks of the 17th century and the collecting tastes of the era, Van Roestraten frequently included imported goods in his still lifes, most notably Chinese porcelain. Blue-and-white Wanli or Kangxi porcelain, as well as reddish-brown YiXing stoneware teapots, often appear in his compositions.

The inclusion of these items served multiple purposes. They added an element of the exotic and fashionable, signalling the owner's wealth and worldliness. They also provided visual interest through their distinct shapes, colours, and surface decorations, contrasting with the European silverware and glassware. The presence of tea wares, like teapots and cups, also points to the growing popularity of tea consumption in England during this period. His accurate depiction of these specific types of ceramics provides valuable documentation of the kinds of Asian goods reaching European markets.

Representative Works

Several works exemplify Van Roestraten's style and thematic concerns:

Still Life with Candlestick: This title suggests a typical Vanitas arrangement. Based on the provided description, it likely featured objects symbolizing transience: an extinguished or near-extinguished candlestick (life burning out), perhaps a single flower (beauty fading), and a pocket watch (time's relentless march). Such works invite quiet contemplation on mortality through meticulously rendered, everyday objects imbued with deeper meaning. The interplay of light on the metal candlestick and watch would likely be a key feature.

The Licentious Kitchen Maid (c. 1665): As a genre scene, this work shifts focus from inanimate objects to human interaction, albeit with a moral message. It likely depicts a scene involving a kitchen maid engaged in behaviour considered improper or suggestive, perhaps involving flirtation or indulgence. Such works often walked a fine line between critique and titillation, reflecting societal preoccupations with class, gender roles, and morality.

Still Life with Caterpillar: The inclusion of a caterpillar adds another layer of symbolism, often representing transformation (potential for change, like a butterfly emerging) or, conversely, the slow process of decay and consumption. This specific detail highlights Van Roestraten's close observation of the natural world, even within the contrived setting of a still life, and his ability to integrate minute elements into the broader symbolic scheme. The rendering of light and shadow on the varied surfaces would be crucial to the overall effect.

These examples illustrate the range within his specialization, from pure Vanitas arrangements to genre scenes with allegorical weight, all executed with his characteristic attention to detail and texture.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Van Roestraten operated within a rich artistic landscape. His primary connection was, of course, to Frans Hals, his teacher and father-in-law, a towering figure of the Dutch Golden Age known for his revolutionary portraits. While Van Roestraten moved away from Hals's primary genre and style, the initial training was formative.

In the realm of still life, he can be compared to Dutch masters like Willem Kalf, known for incredibly luxurious pronkstilleven featuring nautilus cups and Turkish carpets, and Willem Claesz. Heda and Pieter Claesz, who specialized in more monochrome 'banketje' (banquet pieces) often featuring pewter, glassware, and foodstuffs with subtle Vanitas undertones. The work of female still life painters like Rachel Ruysch, celebrated for her intricate flower paintings, also formed part of this vibrant Dutch tradition.

In London, his main contemporaries in portraiture were the highly successful Sir Peter Lely and, later, Sir Godfrey Kneller, both of whom dominated court painting. Van Roestraten's decision (or Lely's advice) to focus on still life may have been strategic to avoid direct competition with these giants. Earlier English portraiture was represented by figures like William Dobson.

While no direct interaction is recorded in the provided snippets, Van Roestraten was also a contemporary of other Dutch titans like Rembrandt van Rijn, whose dramatic use of light and psychological depth influenced generations, and Johannes Vermeer, famed for his serene interior scenes bathed in light. Genre painters like Jan Steen and landscape specialists like Jacob van Ruisdael further illustrate the diversity of the Dutch Golden Age art scene from which Van Roestraten emerged. His career demonstrates how Dutch artistic skills and themes found fertile ground abroad, particularly in England.

Anecdotes and Later Life

Life in 17th-century London was not without its perils. A dramatic incident reportedly occurred during the Great Fire of London in 1666 (though one snippet mentions 1665, the Great Fire was in 1666). During the chaos, Van Roestraten is said to have suffered a serious injury to his hip, possibly from a fall or burn. This injury apparently caused him pain or disability for the rest of his life, a stark reminder of the turbulent times he lived in.

Despite this setback, he continued his successful career in London for many years. His specialization in still life, particularly the prized depictions of silver, ensured a steady market among the English gentry and aristocracy. He remained in London, his adopted home, for the remainder of his life.

Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten died in London on July 10, 1700. He was buried in St. Paul's Churchyard (the snippets mention St Paul's Cathedral, which usually implies burial within the cathedral itself, a high honor; burial in the churchyard is more common, clarification might be needed from primary sources, but the association with St Paul's precinct is noted). His death marked the end of a long and productive career that successfully navigated the art worlds of both the Netherlands and England.

Legacy and Conclusion

Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten occupies a unique position as a Dutch Golden Age painter who achieved significant success primarily outside the Netherlands. Trained by Frans Hals, he skillfully adapted his talents to the demands of the English market, becoming a leading specialist in still life painting, particularly renowned for his exquisite renderings of silver.

His work is characterized by technical precision, a sophisticated understanding of light and texture, and the frequent incorporation of Vanitas themes, reflecting on the nature of wealth, time, and mortality. While perhaps overshadowed in general art history surveys by portraitists like Hals, Rembrandt, or Lely, Van Roestraten was highly esteemed in his time for his specific skills. His paintings were sought after by collectors and provide valuable insight into the tastes and preoccupations of the late 17th-century English elite.

He successfully translated the Dutch pronkstilleven and Vanitas traditions for a new audience, contributing to the cross-cultural artistic exchange between the Netherlands and England. His detailed depictions of silverware, Chinese porcelain, and other luxury items remain visually captivating and serve as important documents of material culture. Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten's legacy lies in his mastery of a specialized genre and his successful career as a Dutch artist thriving in the competitive London art world.