Edward Hicks stands as one of America's most beloved and distinctive folk artists. Living from 1780 to 1849, he was a man of deep religious conviction, a devoted Quaker minister, and a painter whose works, particularly his iconic "Peaceable Kingdom" series, continue to resonate with their messages of harmony, simplicity, and spiritual aspiration. Though he lacked formal academic training, his art possesses a unique power, clarity, and sincerity that transcends the boundaries of traditional folk art, offering a window into the cultural, religious, and personal landscape of early 19th-century America.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Edward Hicks was born on April 4, 1780, in Attleborough (now Langhorne), Bucks County, Pennsylvania. His early life was marked by upheaval. His mother, Catherine Hicks, died when he was just eighteen months old. His father, Isaac Hicks, a loyalist to the British Crown, faced financial ruin and property confiscation after the American Revolution. Young Edward was subsequently taken in and raised by Elizabeth Twining and her husband, David Twining, prominent Quakers in the community. This upbringing proved to be profoundly influential, immersing him in the tenets and practices of the Society of Friends, which would shape his entire life and artistic output.

The Quaker faith, with its emphasis on pacifism, simplicity, equality, and the "inner light" or direct experience of God, provided a moral and spiritual compass for Hicks. The Twinings were kind and provided a stable home, and it was on their farm that Hicks developed an appreciation for the natural world, an element that would later feature prominently in his paintings. His formal schooling was limited, as was common for many at the time, but his experiences within the Quaker community and his later apprenticeship provided practical education.

At the age of thirteen, in 1793, Hicks was apprenticed to William and Henry Tomlinson, coach makers in Attleborough. This seven-year apprenticeship was crucial for his artistic development. He learned the craft of ornamental painting, which involved decorating coaches with intricate designs, lettering, and imagery. This trade required precision, a good sense of color and composition, and the ability to execute detailed work – skills that would later be evident in his easel paintings. He became proficient in grinding pigments, applying paint smoothly, and creating visually appealing decorative elements.

A Craftsman and a Quaker

Upon completing his apprenticeship in 1800, Edward Hicks initially attempted to establish his own coach-making business. However, he found it challenging to manage the financial aspects of the enterprise. For a period, he worked as a journeyman painter, traveling and taking on various decorative painting jobs. This included painting signs for taverns and businesses, household furniture, and other utilitarian objects. These experiences further honed his skills and exposed him to a variety of popular imagery and design motifs.

In 1803, a pivotal year, Hicks married Sarah Worstall, a fellow Quaker from a respected local family. Their marriage was a long and supportive one, and they would eventually have five children. The responsibilities of family life likely spurred him to seek more stable employment. Also in 1803, he formally joined the Middletown Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends, solidifying his commitment to the Quaker faith that had nurtured him.

His dedication to Quakerism grew, and by 1811, he felt a calling to the ministry. In 1812, he was officially recognized as a Quaker minister. This role became central to his identity. Hicks was a passionate and eloquent speaker, and he traveled extensively throughout Pennsylvania, New York, Maryland, Virginia, Ohio, and even into Canada, preaching Quaker principles. His ministry, however, often brought him into financial straits, as Quaker ministers traditionally served without pay. Painting, therefore, remained a necessary means of supporting his family.

The Artist's Path: From Decoration to Devotion

For many years, Hicks viewed his painting primarily as a trade, a way to earn a living. There was a certain tension within Quakerism regarding the arts. Some Friends viewed artistic pursuits as worldly vanities, potentially distracting from spiritual devotion and simplicity. Hicks himself sometimes expressed ambivalence about his painting, worrying that it might be an indulgence. However, he also recognized its utility in providing for his family and, increasingly, as a vehicle for expressing his deeply held religious beliefs.

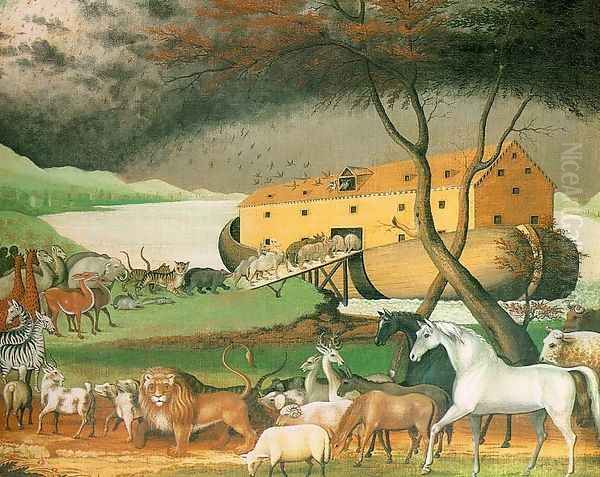

His early non-commissioned works often drew from popular prints and illustrations, a common practice for self-taught artists of the era. He would adapt these sources, imbuing them with his own distinct style and symbolic meaning. His transition from purely decorative work to more ambitious easel paintings was gradual. He began creating landscapes, historical scenes, and, most importantly, religious allegories.

The development of his artistic style was characterized by clear outlines, bright, often unblended colors, a flattened perspective, and meticulous attention to detail. While these are hallmarks of folk or "naive" art, Hicks's compositions are often more complex and thoughtfully organized than those of many of his contemporaries. His experience in sign painting likely contributed to his strong sense of design and his ability to create visually impactful images.

The "Peaceable Kingdom": A Defining Vision

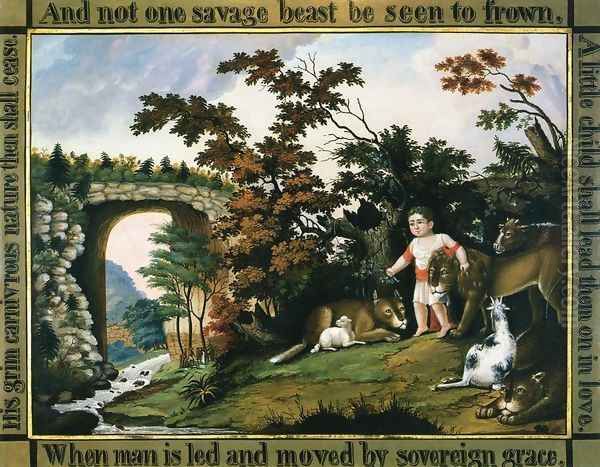

Edward Hicks is most renowned for his series of paintings titled "The Peaceable Kingdom." He created at least 62 versions of this subject between roughly 1820 and his death in 1849. The theme is drawn directly from the prophecy in the Book of Isaiah (11:6-9): "The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them." This biblical passage envisions a utopian state of peace and harmony where natural predators and prey coexist peacefully under the guidance of divine innocence.

For Hicks, this theme was not merely a picturesque biblical illustration; it was a profound allegory for his spiritual aspirations and his hopes for the Society of Friends and for humanity at large. The animals, rendered with a charming, almost gentle quality despite their wild nature, symbolize the reconciliation of opposing forces. The serene child often at the center embodies innocence and the guiding spirit of God.

Many versions of "The Peaceable Kingdom" also include a vignette in the background depicting William Penn's treaty with the Lenape (Delaware) Indians. This historical event, a cornerstone of Pennsylvania's founding mythology, represented for Hicks a real-world example of peaceful coexistence and just relations, echoing the spiritual harmony of Isaiah's prophecy. Penn, a fellow Quaker, was a figure of immense respect for Hicks. By juxtaposing the biblical prophecy with this historical scene, Hicks linked the ideal with the attainable, suggesting that peace was not just a heavenly dream but a practical possibility on Earth.

The evolution of the "Peaceable Kingdom" series reflects Hicks's own spiritual journey and the internal conflicts within the Society of Friends. In the 1820s, Quakerism experienced a significant schism, dividing into "Hicksite" (followers of his cousin, Elias Hicks, who emphasized the inner light and a more liberal theology) and "Orthodox" factions. Edward Hicks was a staunch supporter of Elias Hicks. The turmoil and division deeply troubled him, and his "Peaceable Kingdom" paintings from this period sometimes show more agitated animals or a more somber mood, reflecting his anxieties and his fervent prayers for reconciliation within the Quaker community. Later versions often exude a greater sense of calm and resolution.

Other Notable Works and Themes

While "The Peaceable Kingdom" is his signature work, Edward Hicks painted a variety of other subjects that also reveal his artistic concerns and his connection to his community and environment.

His farmscapes, such as "The Cornell Farm" (c. 1848) and "The Residence of David Twining" (c. 1845-1847), are affectionate portrayals of rural life. These paintings are not just topographical records but celebrations of agrarian virtue, order, and the bounty of the land. They often feature meticulously rendered livestock, a testament to his keen observation and perhaps his early exposure to farm life at the Twinings'. These works demonstrate his skill in composition and his ability to create a sense of idyllic harmony.

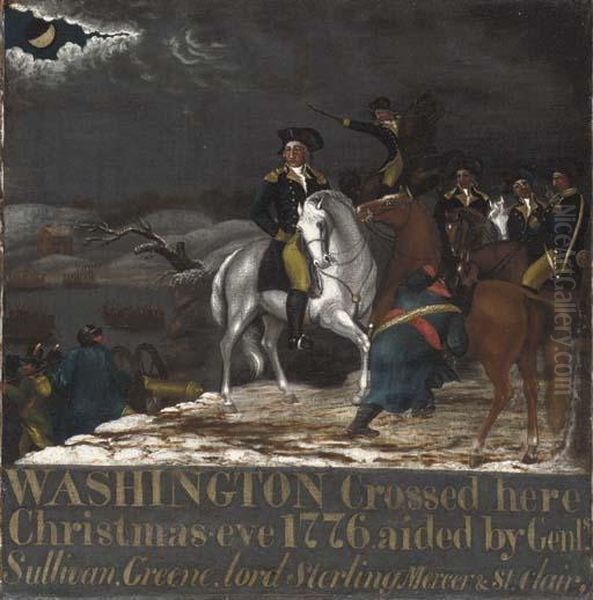

Hicks also painted historical and patriotic subjects. "Penn's Treaty with the Indians" (c. 1840-1844), which often appeared in the background of his "Kingdoms," was also produced as a standalone subject. He painted scenes from American history, such as "Washington at the Delaware," based on Thomas Sully's well-known composition. These works reflect the burgeoning national consciousness of the young United States.

Less common, but still part of his oeuvre, are portraits and signboards. His signboards, like the one for the Newtown Library Company or various inns, showcase his skill in lettering and bold, clear design, directly reflecting his trade.

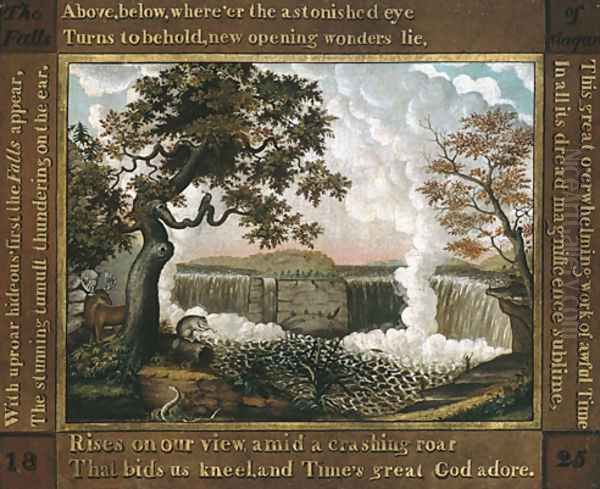

Throughout his work, Hicks often incorporated verses or inscriptions, further emphasizing the moral or religious message of the painting. This integration of text and image is characteristic of much folk art and underscores his didactic intent.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Edward Hicks was fundamentally a self-taught artist in the realm of easel painting, though his apprenticeship provided a strong foundation in the mechanics of painting. His style is often described as "primitive" or "naive," terms that refer to art created by individuals without formal academic training. Such art often features:

Flattened Perspective: Objects and figures may appear to lack true depth, arranged in planes rather than receding into a convincing three-dimensional space.

Strong Outlines: Figures and elements are often clearly delineated.

Bright, Pure Colors: Colors are often applied directly and with less subtle blending or shading than in academic art.

Attention to Detail: Specific elements, particularly those of symbolic importance to the artist, may be rendered with great care and precision.

Intuitive Composition: While perhaps not adhering to academic rules of composition, his arrangements are often balanced and visually engaging.

Hicks's technique involved careful drawing, often transferred or adapted from prints, followed by the application of oil paints, typically on canvas or wood panel. His experience grinding pigments for coach painting would have given him a good understanding of his materials. His brushwork is generally smooth and controlled, aiming for clarity of form.

The charm of Hicks's work lies in its sincerity and directness. There is an unpretentious quality to his paintings, a sense that he is communicating his vision as clearly and honestly as possible. The animals in his "Peaceable Kingdoms," for example, often have expressive, almost human-like eyes, conveying a sense of gentle awareness.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Edward Hicks worked during a period of significant development in American art. The early to mid-19th century saw the rise of the Hudson River School, America's first true school of landscape painting, with artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand creating majestic and romantic depictions of the American wilderness. Portraiture was also a prominent genre, with artists like Gilbert Stuart, Thomas Sully, and Rembrandt Peale capturing the likenesses of the nation's leading figures. His own cousin, Thomas Hicks, became a successful academic portrait and genre painter.

Hicks's work stands apart from these academic traditions. He was part of a vibrant, though less formally recognized, tradition of American folk art. This tradition included itinerant portrait painters like Ammi Phillips and Erastus Salisbury Field, decorative painters like Rufus Porter (known for his murals), and other self-taught artists who created a wide range of paintings, sculptures, and other art forms for their local communities. Other notable folk artists of the general era include Joshua Johnson, one of the earliest documented African American professional painters, and Eunice Pinney, known for her watercolors.

While Hicks may have been aware of some academic art through prints, his primary artistic community was likely other craftsmen and local artisans. He admired the work of artists whose prints he copied, such as Richard Westall, whose illustrations of the Bible influenced some of Hicks's "Peaceable Kingdom" compositions. He also copied engravings after history paintings by artists like Benjamin West, a Pennsylvania-born painter who became president of the Royal Academy in London.

The comparison with Joseph Pickett (1848-1918), another Pennsylvania folk painter from New Hope (near Hicks's Newtown), is often made, though Pickett was of a later generation. Both artists shared a meticulous approach and a strong sense of local identity in their work, though Pickett's style was perhaps even more idiosyncratic, often incorporating built-up textures.

Challenges, Recognition, and Legacy

Throughout his life, Edward Hicks grappled with the perceived conflict between his artistic pursuits and the Quaker testimony of simplicity. He sometimes referred to painting as one of his "besetting sins" and lamented the time and resources it consumed. Yet, he clearly derived satisfaction from it and recognized its power to convey his spiritual messages. His financial situation was often precarious, and painting was a necessary income source.

During his lifetime, Hicks was known primarily as a Quaker minister and a skilled craftsman. His easel paintings were appreciated by a local circle of friends, family, and patrons, often fellow Quakers who understood and valued the religious themes in his work. He did not exhibit in major art academies or seek recognition within the established art world of cities like Philadelphia or New York.

It was not until the 20th century, with the growing interest in American folk art, that Edward Hicks's work gained widespread national and international recognition. Collectors and art historians began to appreciate the unique aesthetic qualities and profound spiritual content of his paintings. Key figures in this "rediscovery" included Holger Cahill, who featured folk art prominently in exhibitions in the 1930s, and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, whose collection formed the basis of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Today, Edward Hicks is considered one of the foremost figures in American folk art. His "Peaceable Kingdom" paintings are iconic and are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Worcester Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

His enduring appeal lies in the sincerity of his vision, the charm of his style, and the universal message of peace and harmony that his art conveys. He transformed a biblical prophecy into a deeply personal and uniquely American artistic statement. His work reminds us of a time when art, faith, and everyday life were more closely intertwined, and his paintings continue to inspire with their gentle yet powerful call for a world where the lion and the lamb can indeed lie down together.

Edward Hicks passed away on August 23, 1849, in Newtown, Pennsylvania, leaving behind a legacy not only as a devoted minister but as an artist whose unique vision captured the spirit of a young nation and the enduring human aspiration for peace. His art serves as a testament to the power of self-taught genius and the profound connection between faith and creative expression.