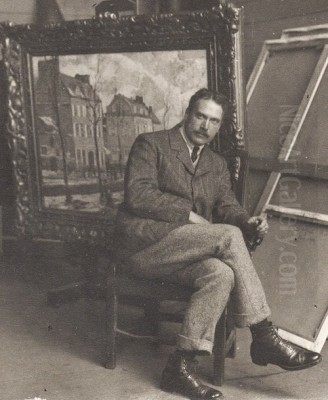

Walter Elmer Schofield stands as a significant figure in the annals of American art, a painter whose canvases vibrantly capture the essence of the landscapes he encountered, from the snow-laden fields of Pennsylvania to the sun-drenched coasts of Cornwall and the rugged terrains of the American Southwest. An artist whose career bridged two continents, Schofield was a pivotal member of the Pennsylvania Impressionist school, also known as the New Hope School, and his work is celebrated for its robust energy, bold brushwork, and profound connection to the natural world. This exploration delves into the life, artistic evolution, key works, and enduring legacy of a painter who masterfully translated the fleeting moments of nature onto canvas.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Philadelphia

Walter Elmer Schofield was born on September 10, 1867, in the bustling city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, into a prosperous family. His father was a successful businessman, providing a comfortable upbringing for young Walter. This environment likely afforded him the freedom to pursue his artistic inclinations later in life. His formal education began with a year at Swarthmore College, a respected Quaker institution near Philadelphia. However, the call of art proved stronger than other academic pursuits.

In 1889, Schofield enrolled at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), one of America's oldest and most esteemed art schools. This was a formative period for Schofield, where he studied under the influential painter Thomas Anshutz. Anshutz, himself a student of Thomas Eakins, emphasized a rigorous approach to drawing, anatomy, and direct observation, instilling a strong foundational discipline in his students. At PAFA, Schofield not only honed his technical skills but also forged lifelong friendships with fellow students who would also become notable artists, including William Glackens and Henry McCarter, and developed a close association with Edward Redfield, another future stalwart of Pennsylvania Impressionism. These early connections would prove influential throughout his career, fostering a community of artists exploring new modes of expression.

The Parisian Influence: Embracing Impressionism

Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Schofield recognized the importance of experiencing European art firsthand, particularly the revolutionary movements emanating from Paris. In 1892, he embarked on a journey to the French capital, the epicenter of the art world at the time. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe. There, he continued his studies, likely under figures such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Gabriel Ferrier, and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, who, while academic in their own right, presided over an institution that allowed for diverse artistic exploration.

It was in Paris and through his travels in France that Schofield was profoundly exposed to and influenced by French Impressionism. The works of artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, with their emphasis on capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere through broken color and en plein air (outdoor) painting, resonated deeply with him. This exposure was transformative, guiding Schofield away from the tighter, more academic styles towards a more vibrant, immediate, and personal interpretation of the landscape. He began to adopt the Impressionist palette and techniques, focusing on the sensory experience of being in nature.

A Transatlantic Career: England and America

In 1897, Schofield married Muriel Charlotte Redmayne. Following their marriage, the couple made their primary residence in England, initially in Southport and later settling in the picturesque coastal region of Cornwall, a haven for artists drawn to its dramatic scenery and unique light. Despite living abroad, Schofield maintained strong ties to the United States, frequently crossing the Atlantic to exhibit his work, engage with the American art scene, and paint the landscapes of his homeland. His career thus became a transatlantic endeavor, with his artistic identity shaped by experiences on both sides of the ocean.

This dual residency allowed Schofield to draw inspiration from diverse environments. The rugged cliffs and fishing villages of Cornwall offered a different character of landscape compared to the rolling hills and river valleys of Pennsylvania. He would often spend winters in the United States, particularly in Pennsylvania, capturing its iconic snow scenes, and summers in England or France, painting the lush, verdant landscapes under different atmospheric conditions. This regular movement enriched his artistic vocabulary and provided a continuous stream of fresh subject matter.

The Essence of Schofield's Art: Subject, Technique, and Style

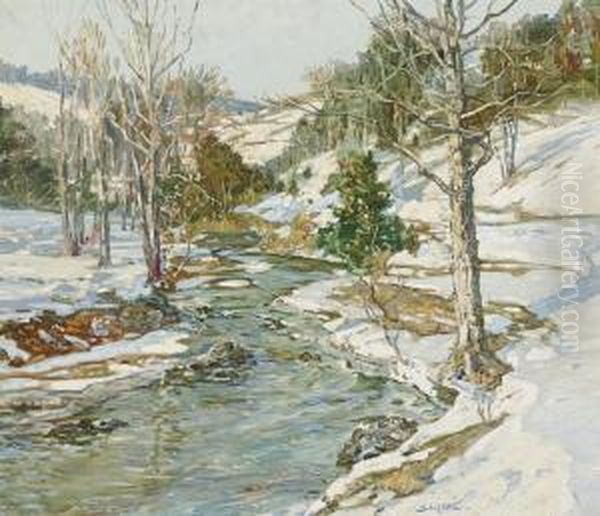

Walter Elmer Schofield is best known for his vigorous and masculine landscape paintings, particularly his depictions of snow. He possessed an uncanny ability to convey the crispness of winter air, the subtle tonalities of snow under varying light conditions, and the stark beauty of a winter-bound world. His snow scenes are not merely white; they are alive with blues, violets, pinks, and ochres, reflecting the ambient light and the underlying forms of the land. He often painted large canvases, working directly from nature even in harsh weather, a testament to his dedication and physical stamina.

His technique was characterized by bold, decisive brushstrokes, often applied with a loaded brush, creating a textured, impasto surface that added to the dynamism of his compositions. While clearly an Impressionist in his concern for light and atmospheric effect, Schofield's work often retained a strong sense of underlying structure and form, a legacy perhaps of his academic training under Anshutz. He was a master of composition, skillfully arranging elements to create a sense of depth and balance, drawing the viewer into the scene.

Beyond snow, Schofield excelled at portraying the changing seasons. His autumnal landscapes blaze with color, and his depictions of flowing water, whether a rushing river or the coastal tides, are imbued with a sense of movement and power. He also painted the more pastoral landscapes of England and the vibrant, sun-filled scenery of the American Southwest later in his career, demonstrating his versatility and his keen observational skills in different climates and terrains.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several paintings stand out in Schofield's oeuvre, exemplifying his artistic vision and technical prowess.

Center Bridge, Across the River: An early success, this work earned him a prestigious medal from the Carnegie Institute. It showcased his burgeoning talent for capturing the American landscape with a fresh, direct approach.

The White Frost: This painting is a quintessential example of Schofield's ability to depict the serene yet stark beauty of a Pennsylvania winter. It reflects the tranquility of the rural landscape, with subtle gradations of color capturing the chill and stillness of a frosty morning.

Nearing Spring: In this work, Schofield masterfully portrays the transitional period between winter and spring. The canvas is often suffused with a warmer light, with hints of emerging life amidst the lingering snow, perhaps through the use of warmer orange and golden hues in the sunlight.

Early Winter Morning: This piece often depicts a scene along one of Pennsylvania's industrial canals, showcasing Schofield's interest in the interplay between nature and human activity. The crisp morning light and the reflections in the icy water are rendered with his characteristic vigor.

McLegrenow Farm: This painting is noted for its skillful use of color and compositional balance, demonstrating Schofield's ability to find beauty and harmony in the cultivated, working landscape. It highlights his method of combining direct observation with studio refinement to achieve the final effect.

Winter's Rush (or Rapids in Winter): This dynamic composition, depicting a fast-flowing river amidst a snowy landscape, is one of his most celebrated. A version of this subject achieved a record auction price for the artist, underscoring its appeal and his mastery in conveying the raw energy of nature.

These works, among many others, are held in important public and private collections, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia, which has a significant holding of his works, partly due to family donations.

Contemporaries and Artistic Circles: The Pennsylvania Impressionists

Schofield was a leading figure among the Pennsylvania Impressionists, a group of artists centered around New Hope, Bucks County, along the Delaware River. This group, which also included Edward Redfield, Daniel Garber, Gardner Symons (a close friend with whom Schofield often painted), Robert Spencer, and Charles Rosen, developed a distinctly American brand of Impressionism. They were known for their robust, often large-scale depictions of the regional landscape, with a particular emphasis on snow scenes and a vigorous, direct painting technique.

While these artists shared a common geography and a general stylistic approach, each maintained a unique artistic voice. Schofield's style was often compared and sometimes contrasted with that of Edward Redfield. Both were known for their powerful snow scenes, but Schofield's work, while equally energetic, sometimes exhibited a greater concern for decorative pattern and a slightly more lyrical quality compared to Redfield's often more rugged naturalism.

Their relationship, though initially friendly from their PAFA days, became strained. Redfield famously accused Schofield of plagiarizing his compositional ideas, particularly in their shared subject matter of snow-covered Pennsylvania landscapes. Schofield reportedly acknowledged some influence, but the dispute created a lasting tension. Despite this, both artists continued to be leading exponents of the Pennsylvania Impressionist style, and Redfield's powerful approach undoubtedly left an impression on Schofield, as it did on many landscape painters of the era.

Beyond the New Hope School, Schofield was connected to a broader network of American artists. His early friendship with William Glackens, who would become a key member of "The Eight" and the Ashcan School, linked him to a more urban-focused realism, even if Schofield's own path remained firmly rooted in landscape. Robert Henri, the charismatic leader of "The Eight," was another contemporary from his PAFA days, and though their artistic subjects differed, they shared a commitment to a vital, American form of art, independent of European academic constraints. Other prominent American Impressionists active during Schofield's career included Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and Theodore Robinson, who, like Schofield, adapted French Impressionist principles to American subjects and sensibilities.

Later Years, Travels, and Continued Recognition

Schofield continued to paint with undiminished energy throughout his life. His travels extended beyond Pennsylvania and Cornwall. He made several trips to the American Southwest, including California, Arizona, and New Mexico, where he was captivated by the brilliant light and dramatic, arid landscapes. These works show a different palette, responding to the intense colors and unique geological formations of the region. He even taught for a period in San Pedro, Los Angeles, where he developed an interest in painting the bustling fishing harbor and its boats.

His artistic achievements garnered significant recognition during his lifetime. He received numerous awards, including the Hallgarten Prize from the National Academy of Design (1901), the Jennie Sesnan Gold Medal from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1903 and 1914), a silver medal at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo (1901), a gold medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco (1915), and the Keith Spalding Prize from the Art Institute of Chicago. His international reputation was solidified by his election to the Royal Society of British Artists and the Royal Institute of Oil Painters in Great Britain.

Schofield was known for his outgoing and affable personality. He was a keen sportsman, enjoying hunting and fishing, activities that further deepened his connection to the outdoors he so loved to paint. His home, whether in England or when visiting family in the U.S., was often a lively place. His niece, Sarah Phillips, and granddaughter, Margaret "Peg" Phillips, fondly remembered his visits.

Market Presence and Auction Highlights

Walter Elmer Schofield's paintings have long been sought after by collectors of American Impressionism. While a comprehensive list of all auction records is extensive, certain sales highlight the market's appreciation for his work. A significant moment occurred in December 2004, when his painting, often titled Winter's Rush or Rapids in Winter (the specific title can vary for similar subjects), sold at Sotheby's in New York for $456,000. This price was reported as a world auction record for the artist at the time and demonstrated the strong demand for his prime-subject, high-quality snow scenes.

His works appear regularly at major auction houses specializing in American art. The value of his paintings typically depends on factors such as size, subject matter (snow scenes and vibrant Cornish coastal scenes are particularly prized), condition, provenance, and the period in which it was painted. His large, dynamic winter landscapes generally command the highest prices. The consistent presence of his work in museum collections also underpins his market value and historical importance.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Walter Elmer Schofield passed away on March 1, 1944, in Cornwall, England, leaving behind a rich legacy of art that continues to resonate with audiences. His contribution to American Impressionism, particularly within the Pennsylvania school, is undeniable. He brought a unique blend of robust energy, keen observation, and sophisticated color sense to his landscapes. His ability to capture the essence of a place, whether the frozen stillness of a Pennsylvania winter or the sunlit vibrancy of a Cornish summer, remains compelling.

His legacy is preserved not only through his paintings in museums and private collections but also through the continued appreciation for the plein air tradition he championed. The Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia, through the generous donations of his family, including his niece Sarah Phillips and granddaughter Margaret "Peg" Phillips, holds a significant collection of his works, offering a valuable resource for the study and appreciation of his art.

Schofield's dedication to painting directly from nature, often under challenging conditions, and his ability to translate the raw, sensory experience of the landscape into powerful, evocative canvases, secure his place as one of America's foremost Impressionist painters. His work serves as a vibrant testament to the beauty and power of the natural world, seen through the eyes of a passionate and skilled artist. He remains an inspiration for landscape painters and a beloved figure for art enthusiasts who appreciate the vigor and authenticity of American Impressionism.