Amédée de La Patellière, born Amédée Marie Dominique Dubois de La Patellière on July 5, 1890, in Vallet, Loire-Atlantique, France, and who passed away prematurely on January 9, 1932, in Paris, remains a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early 20th-century French painting. His work, characterized by a profound connection to the earth, a deep humanism, and a style often described as "Poetic Realism," offers a contemplative counterpoint to the more radical avant-garde movements of his time. He carved a unique niche for himself, creating art that resonated with a quiet intensity, celebrating the enduring rhythms of rural life and the dignity of its inhabitants.

His oeuvre, though developed over a relatively short career, stands as a testament to an artist who sought harmony and a timeless truth in his subjects, often finding it in the landscapes of the Vendée and Brittany, and in the stoic figures that populated them. La Patellière’s art is one of introspection, subtle emotion, and a masterful command of composition and color, which, while rooted in tradition, possessed a distinctly modern sensibility.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born into an aristocratic family, Amédée de La Patellière's early life was steeped in the traditions and landscapes of western France. This upbringing would profoundly influence his thematic concerns throughout his career. While details of his earliest artistic inclinations are not extensively documented, it is clear that his path led him towards a formal art education, a common trajectory for aspiring artists of his era.

He initially studied in Nantes, where he formed a friendship with Gérard Cochet, who would also go on to become a painter and engraver. This early period in Nantes likely provided him with foundational skills and exposure to the regional artistic milieu. However, like many ambitious young French artists, Paris was the ultimate destination for serious artistic training and career development.

La Patellière enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian in Paris, a private art school that had, for decades, served as a vital alternative or supplement to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. At the Académie Julian, he studied under Jean-Paul Laurens, a respected academic painter known for his historical scenes. This period, from approximately 1910 to 1912, would have exposed La Patellière to a diverse range of artistic influences and a vibrant community of fellow students, some of whom, like Jean Arp, Fernand Léger, and Jacques Villon, were exploring more avant-garde paths.

The Crucible of War: A Defining Experience

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 irrevocably altered the course of European history and the lives of millions, including Amédée de La Patellière. He served in the French military throughout the conflict, from 1914 to 1918. The harrowing experiences of trench warfare, the widespread destruction, and the profound human suffering he witnessed left an indelible mark on his psyche and, consequently, on his artistic vision.

While he did produce some works directly referencing the war, such as his "Les tableaux de guerre et de paix" (Paintings of War and Peace), the more significant impact of the war was a deepening of his humanism and a turning away from purely aesthetic or experimental concerns towards a more profound, emotionally resonant art. The war perhaps stripped away any youthful inclination towards fleeting artistic fashions, instilling in him a desire to connect with more enduring, fundamental aspects of human existence.

This period of intense experience likely contributed to the gravitas and contemplative mood that pervades much of his mature work. The search for peace, stability, and the timeless values of rural life, which became central themes in his art, can be seen as a response to the chaos and brutality of the war years. It fostered a style that, while not explicitly narrative, was imbued with a sense of lived experience and a quiet empathy for his subjects.

The Emergence of a Personal Style: Poetic Realism

Following the war, La Patellière's artistic voice began to fully emerge. He became associated with a tendency in French art often termed "Poetic Realism." This was not a formally organized movement with a manifesto, but rather a shared sensibility among a group of artists who sought to depict reality with a heightened sense of emotion, atmosphere, and often a touch of melancholy or nostalgia, without resorting to overt sentimentality. These artists, including figures like André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Marcel Gromaire, and to some extent, the later, more somber works of Maurice de Vlaminck, favored figurative art and often focused on everyday subjects, landscapes, and the human condition.

La Patellière’s version of Poetic Realism was deeply personal. His paintings often depict the rural landscapes of the Vendée and Brittany, regions he knew intimately. These are not merely picturesque scenes but are imbued with a sense of timelessness and a deep connection between the land and its people. His subjects frequently include peasants at work or rest, mothers with children, solitary figures in contemplation, and animals, particularly horses and cattle, rendered with a profound understanding of their form and character.

His color palette, while capable of brightness, often leaned towards earthy tones – ochres, browns, muted greens, and deep blues – which contributed to the grounded, authentic feel of his work. However, he was also adept at using more vibrant, luminous colors, especially in his depictions of light and atmosphere, which distinguished his work from some of his more somber contemporaries. His brushwork was typically solid and constructive, sometimes employing a thick impasto that gave his surfaces a tactile quality. There's a deliberate, almost sculptural quality to his forms, suggesting an influence from Paul Cézanne, whose emphasis on underlying geometric structure had a lasting impact on many early 20th-century painters.

Themes of Rural Life and Timelessness

A recurring theme in La Patellière's art is the celebration of the natural rhythms of life and the pursuit of an almost pastoral ideal, a modern interpretation of the "bucolic" tradition. His paintings often evoke a sense of tranquility and enduring stability, a world away from the rapid industrialization and social upheavals of the early 20th century. This was not an escapist fantasy, but rather a conscious choice to find value and beauty in the seemingly simple and unchanging aspects of rural existence.

His depictions of animals are particularly noteworthy. They are not just incidental elements in a landscape but are often central to the composition, their gazes rendered with a deep, almost human-like intensity. This reflects a profound empathy for the natural world and a recognition of the interconnectedness of all living things. Works featuring farm laborers, women engaged in domestic tasks, or families in quiet moments convey a sense of dignity and resilience.

The landscapes themselves are characters in his paintings. He masterfully captured the specific light and atmosphere of western France, the rolling hills, the intimate farmsteads, and the coastal regions of Brittany. There is a sense of monumentality even in his more modest compositions, a feeling that these scenes represent something fundamental and enduring. He was less interested in capturing a fleeting impression, in the manner of Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, and more focused on conveying the underlying structure and emotional essence of a place.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into His World

Several works stand out as representative of Amédée de La Patellière's artistic vision and technical skill.

La Baigneuse au peignoir blanc (The Bather in a White Robe), also referred to as Baigonneau au peigne blanc, painted around 1924, is a quintessential example of his treatment of the female figure within a natural, intimate setting. The work likely depicts a young woman, perhaps by a river or in a rustic interior, her form rendered with a combination of solidity and gentle curves. The focus on a quiet, personal moment is typical of his approach.

Nature morte (Still Life), with examples dating from the 1920-25 period, showcases his ability to imbue everyday objects with a sense of presence and quiet dignity. Unlike the analytical still lifes of Cubists like Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque, La Patellière's still lifes are more traditional in their arrangement but modern in their simplification of form and emphasis on texture and color harmony.

Personnage au cheval blanc (Figure with a White Horse), created around 1930, is an evocative piece. The white horse, a recurring motif in art history, often carries symbolic weight, and in La Patellière's hands, it likely contributes to a sense of timelessness or a connection to a more mythical, pastoral world. The interaction, or lack thereof, between the figure and the horse would be key to the painting's mood.

Nu allongé devant la fenêtre (Reclining Nude before a Window), executed in watercolor and charcoal, demonstrates his versatility across different media. The theme of the nude by a window is a classic one, explored by artists from Titian to Henri Matisse. La Patellière's interpretation would likely emphasize the interplay of light and shadow, and the contrast between the intimacy of the interior and the world outside.

La Locomotive (The Locomotive), a charcoal drawing, presents an interesting contrast to his more prevalent rural themes. The depiction of a locomotive, a powerful symbol of modernity and industrial progress, shows his engagement with contemporary life, even if his primary focus remained on the agrarian world. This work highlights his skill as a draughtsman.

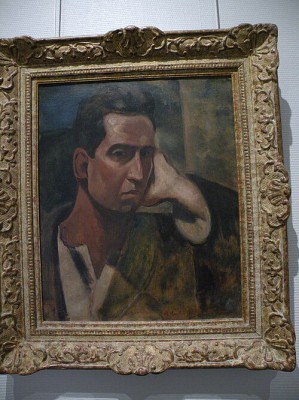

Other common subjects included scenes of maternity, farm life, and portraits, all rendered with his characteristic blend of robust form, subtle emotional depth, and a palette that, while often subdued, could also sing with carefully chosen harmonies of color. His compositions are typically well-balanced, with a strong sense of underlying order, reflecting perhaps a classical temperament filtered through a modern sensibility.

Influences, Contemporaries, and Artistic Context

Amédée de La Patellière's art did not develop in a vacuum. He was keenly aware of the artistic currents of his time, even as he forged his own distinct path. The towering figure of Paul Cézanne, with his emphasis on underlying geometric structure and his methodical construction of form through color, was a significant, if indirect, influence on many artists of La Patellière's generation, and his impact can be sensed in the solidity and compositional rigor of La Patellière's work.

While he moved away from the more radical experiments of Cubism, his early exposure to the Parisian avant-garde, which included figures like Picasso, Braque, and Juan Gris, would have informed his understanding of pictorial space and form. The legacy of Post-Impressionists like Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard, particularly their work in Brittany and their simplification of forms and use of expressive color, might also have resonated with him, especially given his own focus on that region. The monumental calm found in the works of Puvis de Chavannes, a major figure of late 19th-century Symbolism, could also be seen as a precursor to the serene classicism in some of La Patellière's figures.

Among his contemporaries, he shared affinities with other artists associated with Poetic Realism or similar figurative tendencies. André Dunoyer de Segonzac, known for his richly textured landscapes and still lifes, was a close friend. Marcel Gromaire developed a powerful, somewhat stylized figuration that also often depicted scenes of labor and everyday life. Charles Dufresne, another contemporary, explored exotic themes but with a similar richness of color and decorative quality. Even Maurice de Vlaminck, initially a fiery Fauvist alongside André Derain and Matisse, later developed a more somber, expressive realism in his landscapes that shares some atmospheric qualities with La Patellière's work, albeit with a different emotional tenor.

La Patellière’s art can also be seen in the broader context of the "return to order" (rappel à l'ordre) that characterized much European art in the aftermath of World War I. This was a widespread tendency to move away from the radical pre-war avant-gardes towards more classical, figurative, and compositionally stable forms of expression. Artists like André Derain, formerly a leading Fauve, and even Picasso, with his "neoclassical" period, participated in this shift. La Patellière’s commitment to figuration and traditional themes aligned with this broader cultural mood, though his approach was always deeply personal rather than programmatic.

He also existed alongside the continuing traditions of Intimism, as practiced by Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who found profound beauty in domestic scenes, though La Patellière's scope was often broader and more focused on the rural outdoors. And while the Surrealist movement, with figures like Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst, was gaining momentum in the 1920s, La Patellière remained committed to a vision rooted in observable reality, albeit one filtered through a poetic sensibility.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Connections

Amédée de La Patellière achieved notable recognition during his lifetime. He exhibited regularly at the major Parisian Salons, including the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d'Automne, which were crucial venues for artists to showcase their work and gain critical attention. His work was also shown at prominent galleries, such as the Galerie Druet.

His talent and contribution to French art were formally acknowledged when he was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur in 1931, a significant honor. This award underscored his standing within the French art establishment of the period. His paintings were acquired by astute collectors and began to enter public collections, including the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris (now part of the Centre Pompidou) and regional museums, particularly in Nantes.

Beyond the visual arts, La Patellière cultivated friendships with figures from the literary world. He was acquainted with writers and intellectuals such as Pierre-Jean Jouve, a poet and novelist, and the filmmaker René Clair. Henri Barbusse, the author of the powerful anti-war novel Le Feu (Under Fire), was another notable contemporary. These connections suggest an artist engaged with the broader cultural and intellectual currents of his time, and these friendships likely provided mutual intellectual stimulation and enriched his worldview.

Personal Life and Final Years

In 1924, Amédée de La Patellière married Suzanne Lecomte. His personal life, like his art, seems to have been characterized by a degree of quietude and dedication to his craft. He divided his time between Paris and the countryside, particularly the Vendée region, which remained a constant source of inspiration.

His artistic output continued steadily through the 1920s, a period during which he consolidated his style and produced many of his most significant works. He remained dedicated to his themes of rural life, landscape, and the human figure, exploring them with increasing depth and maturity.

Tragically, Amédée de La Patellière's career was cut short by his premature death in Paris on January 9, 1932, at the age of only 41. The exact cause of his death, often cited as a generalized illness or infection, brought an untimely end to a promising and already accomplished artistic journey. His passing was a loss to the French art world, depriving it of a unique voice that offered a compelling alternative to the dominant modernist narratives.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

Despite his relatively short career, Amédée de La Patellière left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its quiet strength, its poetic sensibility, and its profound humanism. While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, his contribution to French figurative painting in the early 20th century is undeniable.

His work is valued for its authentic portrayal of French rural life, capturing a world that was rapidly changing yet possessed of enduring values. He managed to be both traditional and modern: traditional in his choice of subjects and his respect for craftsmanship, yet modern in his simplification of forms, his expressive use of color and texture, and the underlying psychological depth of his portrayals.

Retrospectives of his work, such as the one held at the Musée Galliera (now the Palais Galliera, Musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris) or exhibitions including his paintings at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, have helped to reaffirm his place in art history. His paintings are sought after by collectors who appreciate his unique blend of realism and poetry, and his works remain in important public collections in France and beyond.

Amédée de La Patellière stands as an artist who chose a path of introspection and connection to the earth, creating a body of work that speaks to the enduring human need for beauty, harmony, and a sense of belonging. In a turbulent era, his art offered a vision of serenity and timelessness, a quiet celebration of life's fundamental rhythms that continues to resonate with viewers today. He remains a testament to the power of an art that, while not shouting for attention, whispers profound truths about the human condition and our relationship with the world around us.