Edward Troye stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in nineteenth-century American art. Born in Switzerland and trained in England, he brought a European sensibility to his depictions of the burgeoning American thoroughbred racing scene. While primarily celebrated as one of the foremost equine portraitists of his era, Troye's extensive body of work also offers an invaluable, and often unintentional, visual record of the complex social and racial dynamics of the antebellum South, particularly the integral role of African Americans in the world of horse racing.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

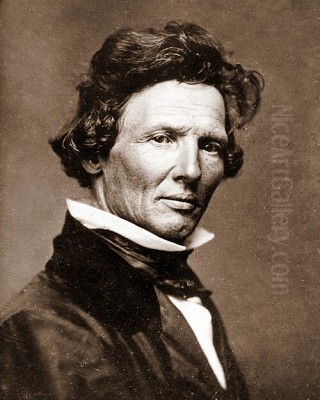

Edward Troye was born on July 12, 1808, in Lausanne, Switzerland, into a family with artistic inclinations. His father, Jean-Baptiste de Troye, was a sculptor of some repute, and his mother, Laure Agasse (sometimes spelled Angasse), also possessed artistic talents. This environment likely fostered his early interest in art. Seeking more formal training and opportunities, the Troye family relocated to England when Edward was a young man.

London, at that time, was a vibrant center for the arts, particularly for sporting and animal painting. Troye immersed himself in this world, seeking instruction from, as he would later claim, "the best masters" in London. While specific details of his tutelage can be elusive, he openly acknowledged the profound influence of leading British animal painters. Chief among these were George Stubbs (1724-1806), whose scientific approach to equine anatomy revolutionized the genre, and John Nost Sartorius (1759-1828), a prolific painter of hunting and racing scenes.

The legacy of artists like Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807), known for his romantic and dramatic horse paintings, and Benjamin Marshall (1768-1835), who captured the vigor of the turf, also permeated the artistic milieu in which Troye trained. James Ward (1769-1859), another contemporary, further contributed to the high standard of animal portraiture in Britain. Troye absorbed these influences, particularly the emphasis on anatomical accuracy, the detailed rendering of musculature and coat, and the ability to capture the individual character of the animal. His British training instilled in him a commitment to realism and a sophisticated understanding of composition that would define his later career.

Arrival in America and Early Career

Around 1830 or 1831, Edward Troye made the pivotal decision to emigrate to the United States, initially settling in Philadelphia. This city was then a major cultural and publishing hub. Troye found early work as an illustrator for magazines, a common entry point for artists seeking to establish themselves. His skills in detailed draftsmanship were well-suited to this medium.

However, his passion and specialized training in animal portraiture, particularly horses, soon led him to seek patronage among the affluent landowners and thoroughbred enthusiasts of the American South and Mid-Atlantic. The culture of horse racing was deeply embedded in these regions, and owners were eager to commission portraits of their prized steeds, which were symbols of wealth, status, and sporting prowess.

Troye's European training and his ability to produce sophisticated, anatomically correct equine portraits set him apart. He began to travel extensively, moving from plantation to stud farm, wherever his skills were in demand. This itinerant lifestyle characterized much of his career, allowing him to capture a wide array of celebrated horses across various states.

The Premier Equestrian Portraitist

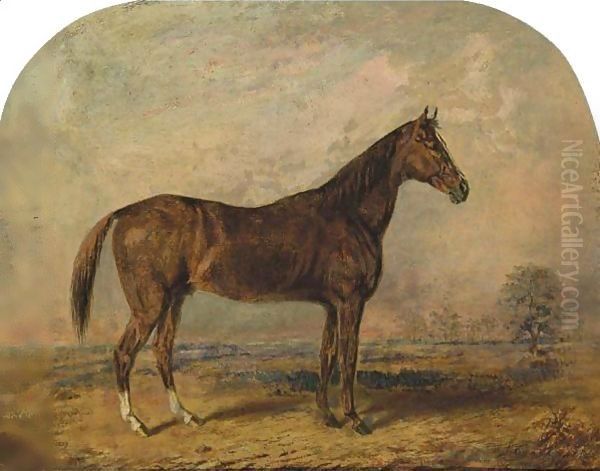

Edward Troye quickly established himself as the preeminent painter of thoroughbred horses in America during the mid-nineteenth century. His reputation was built on his meticulous attention to detail, his understanding of equine conformation, and his ability to convey the spirit and individuality of each animal. Patrons valued his work not just as art, but as accurate records of their finest bloodstock.

He painted many of the most famous racehorses of the era. His canvases became a veritable "who's who" of American turf legends. Among these, Lexington (foaled 1850) was perhaps the most celebrated, a horse of exceptional speed and later a hugely influential sire. Troye painted Lexington multiple times, capturing his power and noble bearing. These portraits often included the African American grooms or trainers who were essential to the horse's success, a recurring and significant feature of Troye's work.

Other notable champions immortalized by Troye include Glencoe, Boston, Reel, and Wagner. His painting of The "Unundefeated" Asteroid (foaled 1861) showcases another legendary horse, depicted with the characteristic precision and quiet dignity that marked Troye's style. He also painted Tobacconist and Trifle, further cementing his status as the go-to artist for equine portraiture. His work was not limited to American-bred horses; he also painted imported English stallions and mares, reflecting the transatlantic nature of thoroughbred breeding.

Troye's patrons were among the wealthiest and most influential figures in the South, such as Alexander Porter of Louisiana, Wade Hampton II and James Chesnut Jr. of South Carolina, and numerous Kentucky breeders. He developed a close working relationship with Duncan F. Kenner of Ashland Plantation in Louisiana, for whom he painted a series of six racehorses in 1845. He also painted portraits of horse owners, such as his depiction of Richard Singleton. These commissions provided him with a steady income and further solidified his reputation.

His style, while rooted in the British tradition of Stubbs and Sartorius, adapted to the American context. He often depicted horses in profile or slightly angled, set against serene landscapes that hinted at the pastoral ideal of the Southern plantation. The focus was invariably on the horse itself, its physical attributes rendered with an almost scientific exactitude.

An Unintentional Chronicler: Depicting African Americans

Beyond the celebrated horses, a unique and historically vital aspect of Edward Troye's legacy is his depiction of the African American men and boys who were the backbone of the American racing industry. In an era when Black individuals were largely invisible or stereotyped in mainstream art, Troye consistently included them in his equine portraits, often with a remarkable degree of individuality and dignity.

These figures were the jockeys, grooms, trainers, and stable hands – enslaved and free – whose expertise was indispensable to the care, training, and racing of thoroughbreds. Troye's paintings, such as those featuring Lexington with his groom Jarret, or other unnamed but clearly delineated Black horsemen, provide a visual testament to their presence and skill. He portrayed these men not as mere accessories, but as integral components of the equestrian world, often highlighting their connection with the horses.

In works like Reality, which depicts the racehorse Reality with an African American groom, or his various portraits of horses with their handlers, Troye captures a sense of professionalism and quiet pride. His rendering of their features, attire, and posture often conveys strength and competence, challenging the demeaning caricatures prevalent at the time. For instance, the groom attending to Lexington is often depicted with a confident, knowing air.

Art historians now recognize Troye as an "accidental historian." While his primary aim was to paint horses for their owners, his canvases inadvertently created a visual archive of these often-unnamed individuals whose contributions were crucial but largely unrecorded in written histories. His work offers a nuanced glimpse into the complex racial dynamics of the antebellum South, where African Americans, despite the oppressive system of slavery, carved out positions of skill and respect within the equestrian sphere. These portrayals stand in contrast to the work of many of his contemporaries who, if they depicted African Americans at all, often did so in subservient or stereotypical roles.

The book Antebellum Sports Illustrated: Representing African Americans in Edward Troye’s Equine Paintings delves deeply into this aspect of his work, analyzing how Troye’s paintings serve as important documents of African American life and labor in the 19th-century South. His detailed portrayals allow for a richer understanding of their roles, moving beyond simple labels of "slave" or "servant" to acknowledge their specialized knowledge and agency within their domain.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Edward Troye's artistic style was characterized by a blend of meticulous realism, particularly in his rendering of horses, and a more conventional approach to landscape and human figures. His primary strength lay in his profound understanding of equine anatomy, likely honed by his study of George Stubbs's seminal work, The Anatomy of the Horse (1766). This allowed him to depict horses with an accuracy that few of his American contemporaries could match.

He paid close attention to the musculature, bone structure, and even the sheen of a horse's coat. Veins are often delicately traced beneath the skin, and the unique markings of each horse are carefully recorded. This precision was highly valued by his patrons, who saw his paintings as faithful representations of their prized animals. His compositions were typically balanced and harmonious, often placing the horse centrally, in a calm, statuesque pose that emphasized its noble qualities.

While his horses were rendered with exceptional skill, his depiction of human figures, including the African American grooms and jockeys, was sometimes considered less anatomically sophisticated. However, he often succeeded in capturing their individual character through facial expressions, posture, and attire. His landscapes, serving as backdrops, were generally serene and somewhat idealized, often featuring distant trees, open skies, and occasionally, glimpses of plantation architecture. These settings provided context without distracting from the primary subject.

Troye advertised his work as being "in the style of Stubbs and Sartorius," consciously aligning himself with the esteemed British tradition. This was a strategic move to appeal to an American market that still looked to Europe for artistic standards. He sought to differentiate himself from domestic competitors like Alvan Fisher (1792-1863) and the French-born Henri Delattre (1801-1876), who were also painting animals and sporting scenes in America. Fisher, for instance, was known for his landscapes and genre scenes that often included animals, while Delattre also specialized in equine subjects.

Troye's palette was generally naturalistic, with rich earth tones and careful attention to the varied colors of horse coats. He worked primarily in oils on canvas, producing works that ranged from modest individual portraits to larger, more complex compositions. His commitment to detail meant that his paintings were not dashed off quickly; they were carefully considered and executed works.

Notable Works Revisited

Several of Edward Troye's paintings stand out not only for their artistic merit but also for their historical significance.

Lexington (various versions): Perhaps his most famous subject, Troye's portraits of Lexington are iconic. One notable version shows the celebrated stallion with his African American groom, often identified as Jarret. The painting highlights Lexington's powerful physique and calm demeanor, while Jarret stands attentively, a figure of quiet authority. This composition underscores the partnership between horse and handler.

Dick Chinn, By Sumpter: Commissioned by a prominent horse owner named Sumpter, this painting showcases a renowned racehorse. It exemplifies Troye's ability to capture the specific characteristics that made a horse a champion, from its conformation to its perceived temperament.

The "Unundefeated" Asteroid: This work portrays another celebrated racehorse, emphasizing its sleek lines and athletic build. The title itself speaks to the horse's legendary status, and Troye’s rendering does justice to its reputation.

Richard Singleton: This portrait of a horse owner, likely with one of his prized animals, demonstrates Troye's capacity for human portraiture, although his primary fame rests on his equine subjects. It provides insight into the social world of his patrons.

Reality with an African American Groom: This painting is a prime example of Troye's inclusion of Black horsemen. The groom is depicted with care, his role clearly essential to the horse's presentation. Such works are invaluable for understanding the integrated, yet deeply unequal, nature of the antebellum racing world.

These, and many other works, are now held in prestigious collections, including the Yale University Art Gallery, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the National Sporting Library & Museum. Their preservation allows for continued study of Troye's artistic contributions and the historical narratives embedded within his canvases.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Edward Troye operated within a burgeoning American art scene, though his specialization set him somewhat apart. In the broader field of American painting, artists like Thomas Cole (1801-1848) and Asher B. Durand (1796-1886) were defining the Hudson River School of landscape painting, capturing the grandeur of the American wilderness. Portraitists such as Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), though of an earlier generation, had established a strong tradition of portraiture, which continued with artists like Thomas Sully (1783-1872), who painted the elite of American society.

In the realm of animal and sporting art, Troye's direct influences, George Stubbs and John N. Sartorius, remained key reference points. In America, Alvan Fisher and Henri Delattre were notable contemporaries also working with animal subjects. Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819-1905), an English-born artist who came to America later than Troye, became known for his paintings of American wildlife and sporting scenes, often with a more dramatic or narrative flair. John James Audubon (1785-1851), while focused on ornithology, shared a commitment to detailed, naturalistic representation of animals, creating a monumental record in The Birds of America.

Troye's work, however, remained uniquely focused on the thoroughbred and the culture surrounding it. He did not engage with the romantic landscapes of the Hudson River School or the historical narratives that other painters explored. His niche was specific, and he dominated it. Later American artists like Frederic Remington (1861-1909) and Charles Marion Russell (1864-1926) would take up equine subjects in the context of the American West, but their style and focus were vastly different, reflecting a changing nation and artistic sensibilities. Troye's contribution lies firmly in the antebellum period and its particular social and cultural preoccupations.

The patronage system of the time also shaped his career. Wealthy plantation owners and breeders were his primary clients, and their desire for accurate, dignified portrayals of their horses dictated the nature of his commissions. This contrasts with artists who relied on public exhibitions or sales through dealers to a broader middle-class audience, a market that was still developing in America.

Later Life, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Edward Troye continued to paint throughout his life, adapting to changing tastes and the upheaval of the Civil War, which profoundly impacted his Southern patrons and the racing industry. He spent time in Kentucky, Alabama, and other states, following the centers of thoroughbred breeding. He also made a trip to the Middle East in the 1850s, commissioned to paint Arabian horses, which were highly valued for their influence on thoroughbred bloodlines.

Despite his prolific output and the esteem in which he was held by horsemen, Troye faced financial difficulties at times, a common plight for artists of the period. He taught art to supplement his income, including a stint at Spring Hill College near Mobile, Alabama.

Edward Troye passed away on July 25, 1874, in Huntsville, Alabama. He left behind an extensive body of work, estimated at over 350 paintings and numerous drawings and prints. While his fame might have been somewhat eclipsed in the decades immediately following his death as artistic styles evolved, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in his work in more recent times.

His legacy is twofold. Firstly, he is recognized as America's foremost nineteenth-century equine artist, a master of animal portraiture whose works are prized for their accuracy and artistry. Secondly, and perhaps more significantly for contemporary scholarship, his paintings serve as invaluable historical documents. They offer a unique window into the world of antebellum thoroughbred racing and, crucially, provide a rare and dignified visual record of the African Americans who were central to that world.

Exhibitions and Scholarly Attention

In recent decades, Edward Troye's work has been the subject of renewed scholarly attention and several important exhibitions, highlighting his artistic skill and historical importance.

In 2010, the University of Kentucky Art Museum hosted "Hoofbeats and Heartbeats: The Horse in American Art," an exhibition that featured works by Troye alongside other prominent American artists who depicted horses, contextualizing his contribution within a broader artistic tradition.

A significant moment for the reassessment of Troye's work was the first modern gallery exhibition dedicated solely to him, held at the Newhouse Galleries in New York City in 2013. This show brought many of his key paintings to a wider audience and stimulated further interest.

The University of Kentucky Art Museum again focused on Troye in 2015 with "Edward Troye: Theme & Variation," an exhibition that specifically explored his prints, demonstrating another facet of his artistic output and his efforts to disseminate his images to a broader public.

Publications have also played a crucial role in re-establishing Troye's significance. The aforementioned Antebellum Sports Illustrated: Representing African Americans in Edward Troye’s Equine Paintings by an array of scholars provides critical analysis of his work's social and racial dimensions. Another publication, Three Kentucky Artists: Joel T. Hart, Samuel W. Price, and Edward Troye, (though the provided source text mentions "Joel, Tilmann Riemenschneider and Edward Troye," historical accuracy points to Kentucky artists like Hart and Price being more contextually grouped with Troye in such a regional study, Riemenschneider being a much earlier German sculptor) explored his impact on the cultural landscape of Kentucky, a key center for thoroughbred breeding. These studies and exhibitions have firmly positioned Troye not just as an animal painter, but as an artist whose work intersects with critical themes in American history and art history.

Conclusion: A Painter of Horses and History

Edward Troye's career spanned a transformative period in American history. As a Swiss-born, British-trained artist, he brought a high level of technical skill to the specialized field of equine portraiture in the United States. He meticulously documented the champions of the American turf, creating a visual lineage of the nation's finest thoroughbreds. His patrons, the elite of the antebellum South, valued his ability to capture the likeness and spirit of their prized animals.

Yet, Troye's enduring importance extends beyond his skill as an animalier. His canvases, often populated by the African American jockeys, grooms, and trainers who were the unsung experts of the racing world, offer a rare and invaluable visual record. In an era that largely ignored or caricatured Black individuals, Troye depicted them with a degree of dignity and individuality that makes his work a vital resource for understanding the complexities of race, labor, and culture in nineteenth-century America. He was, in many respects, an unintentional chronicler, whose dedication to his primary subject – the horse – led him to preserve the images of those who might otherwise have been lost to the historical record. Today, Edward Troye is rightfully recognized not only as a master painter of horses but also as a significant contributor to the visual narrative of American history.