William Sidney Mount stands as a pivotal figure in the development of American art during the 19th century. Born into a young nation still forging its cultural identity, Mount became one of its first and most celebrated genre painters, artists who focused on scenes of everyday life. Forsaking the grand historical narratives or idealized European landscapes favored by some contemporaries, Mount turned his gaze towards the familiar world of rural Long Island, New York. His paintings offer invaluable, often humorous, and insightful glimpses into the activities, social interactions, and burgeoning culture of antebellum America. He captured the spirit of his time and place with a unique blend of realism, warmth, and keen observation, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inform our understanding of American history and art.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

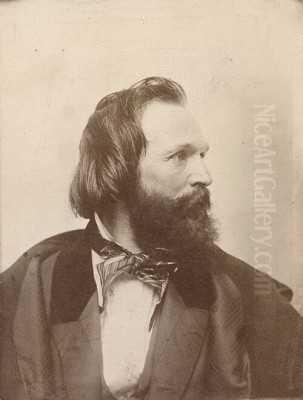

William Sidney Mount was born on November 26, 1807, in the village of Setauket, Long Island, New York. His formative years were spent in nearby Stony Brook, a rural farming community that would profoundly shape his artistic vision and provide the backdrop for many of his most famous works. The landscapes, people, and daily rhythms of Long Island life became deeply ingrained in his consciousness, serving as a constant source of inspiration throughout his career. His connection to this region remained steadfast; despite periods spent in New York City, he always returned to the familiar comforts and rich subject matter of his home ground.

Mount's initial path did not lead directly to art. He spent time working on the family farm before venturing to New York City in 1824. There, he began an apprenticeship not in fine art, but in the craft of sign painting under his elder brother, Henry Mount, who was establishing himself as a decorative and portrait painter. This practical experience likely honed his skills in handling paint and composition, providing a foundation for his later work. Henry's guidance was an important early influence, introducing William to the possibilities of an artistic career.

Seeking more formal training, Mount enrolled at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York City in 1826, shortly after its founding by artists like Samuel F.B. Morse and Asher B. Durand. Here, he immersed himself in the study of drawing from plaster casts of classical sculptures and attended lectures on anatomy and perspective. For a brief period, he also studied with Henry Inman, a leading portrait painter of the day and another influential figure at the Academy. This academic training refined his technical abilities, although his true artistic voice would emerge when he applied these skills to subjects drawn from his own experiences.

The Emergence of a Genre Painter

Mount's early works included some historical paintings and portraits, reflecting the prevailing tastes and training methods of the time. However, he soon found his true calling in genre painting – the depiction of ordinary people engaged in everyday activities. This shift coincided with a growing national interest in American subjects and themes, a cultural movement that sought to define what was unique about the American experience, separate from European traditions. Mount became a leading figure in this artistic exploration.

In 1830, his painting Rustic Dance After a Sleigh Ride was exhibited at the National Academy, signaling his turn towards genre subjects. His talent was quickly recognized, and in 1832, he was elected a full member (Academician) of the National Academy of Design, a significant honor for a young artist. He would continue to exhibit his works there regularly for much of his career, until 1865, establishing his reputation among peers and patrons.

Unlike many of his contemporaries associated with the Hudson River School, such as Thomas Cole or Frederic Edwin Church, who focused on the grandeur and sublimity of the American landscape, Mount centered his art on human activity within that landscape. While influenced by the Hudson River School's appreciation for nature, his primary interest lay in narrative, character, and the social dynamics of rural life. He chose to root his art firmly in the specific locale of Long Island, finding universal themes within the particular details of his community.

Themes and Subjects in Mount's Art

Mount's body of work explores several recurring themes, providing a rich tapestry of 19th-century American life. His paintings often blend observation with gentle humor and a democratic sensibility, reflecting the ideals, and sometimes the contradictions, of Jacksonian America.

Rural Life on Long Island

The heart of Mount's oeuvre is the depiction of life in and around Stony Brook. He painted farmers at work and rest, villagers engaged in trade, children at play, and community gatherings. Works like Bargaining for a Horse (1835) capture the shrewdness and social interaction involved in rural commerce, presenting a scene relatable to his audience. The painting depicts two men intently negotiating over a horse, their body language and expressions conveying the nuances of the transaction. It reflects a world where personal reputation and bargaining skills were essential.

Farmers Nooning (1836) is perhaps one of his most iconic images of rural repose. It shows a group of farmhands taking a midday break during haying season. The composition is dominated by a large central figure of a young African American man sleeping soundly, while white youths engage in playful activities around him. The painting has been interpreted in various ways, seen by some as an idyllic image of pastoral harmony and democratic ease, while others note the underlying racial hierarchies and the differing states of labor and leisure depicted. Regardless of interpretation, it exemplifies Mount's ability to create seemingly simple scenes rich with narrative potential and social observation.

Music and Merriment

Music was not only a frequent subject in Mount's paintings but also a personal passion. He was an accomplished fiddler and even an inventor of musical instruments. This deep connection to music permeates his work, often depicting scenes of communal enjoyment centered around music and dance. Dancing on the Barn Floor (1831) captures the energy and joy of a country dance, highlighting the importance of music in social gatherings.

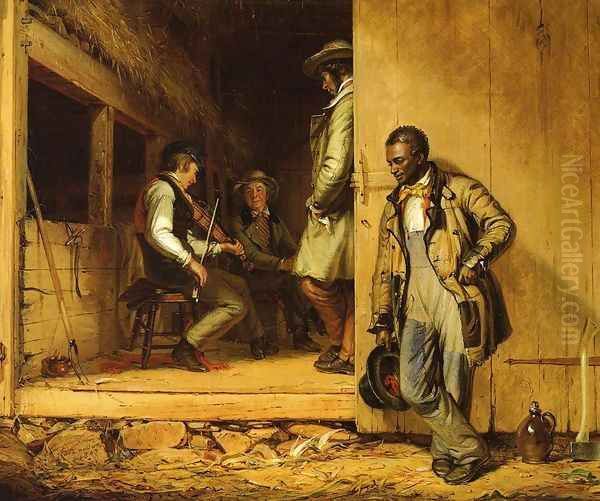

The Power of Music (also known as Music Hath Charms, 1847) is another significant work exploring this theme. It shows a white man playing a fiddle inside a barn doorway, while an African American man listens intently from outside, leaning against the doorframe. The painting subtly explores themes of cultural exchange, shared appreciation for music across racial lines, and perhaps the social barriers that still existed. Mount's brother, Robert Nelson Mount, a dancer and musician himself, sometimes provided inspiration or suggestions for these musical scenes, highlighting the close connection between Mount's art and his personal life.

His interest in music extended beyond depiction. Mount designed and patented a unique type of hollow-backed violin in 1852, which he called the "Cradle of Harmony." He claimed it produced a louder, more resonant tone, making it suitable for playing at lively country dances where the music needed to carry over the noise of the crowd. Several examples of this instrument survive, tangible evidence of his inventive spirit and dedication to music.

Depicting African Americans

William Sidney Mount was one of the first prominent white American artists to depict African Americans with a degree of individuality and sympathy, moving beyond the crude caricatures prevalent in much popular imagery of the time, such as minstrel show posters. Figures like the sleeping man in Farmers Nooning or the listener in The Power of Music are rendered with care and dignity, participating in the life of the community, albeit often in secondary or service roles reflecting the social realities of the era.

His 1856 painting The Banjo Player presents a single figure, focused and engaged in his music-making, portrayed with a sensitivity uncommon for the period. While Mount's depictions were not entirely free from the stereotypes and racial biases of his time, they represented a significant step towards a more humane and nuanced representation of African Americans in American art. Compared to the often derogatory images produced by others, Mount's work offered a more respectful, though still limited, perspective. Later artists, like Eastman Johnson in works such as Negro Life at the South (1859), would explore the lives of African Americans with even greater complexity, but Mount's earlier efforts remain noteworthy.

Narrative and Humor

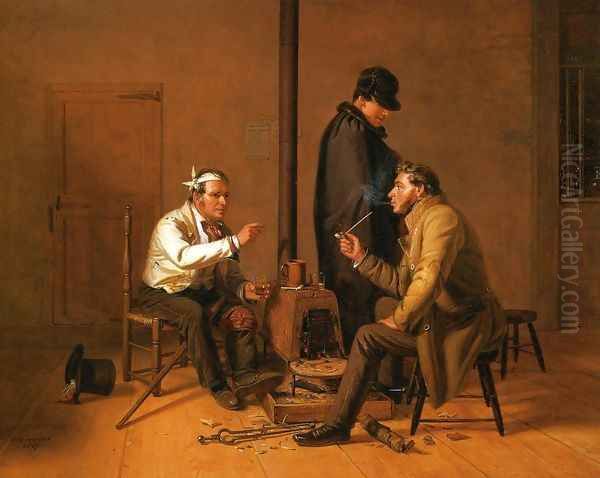

Many of Mount's paintings tell a story or capture a humorous anecdote. He had a keen eye for the small dramas and comedies of everyday life. The Long Story (1837) depicts a group of men in a tavern or country store, one gesturing emphatically as he spins a yarn, while his listeners react with varying degrees of engagement or amusement. The composition draws the viewer into the circle, inviting them to share in the moment.

Raffling for the Goose (1837, also known as The Raffle) shows a group gathered eagerly around a table where a raffle is taking place, the prize being a goose. The varied expressions and postures of the participants create a lively and engaging scene, capturing the anticipation and social dynamics of a community event. Mount's ability to infuse these scenes with gentle humor and relatable human interactions contributed significantly to his popularity. His narrative approach shows an affinity with British genre painters like Sir David Wilkie and William Hogarth, whose prints Mount was known to admire and even own.

Artistic Style and Technique

Mount developed a distinctive style characterized by careful drawing, clear compositions, and an honest, unpretentious approach to his subjects. His realism was based on close observation of people and their environments. He often made numerous preparatory sketches from life, ensuring the accuracy of details, postures, and expressions in his finished paintings.

His compositions are typically well-structured, often employing stable pyramidal or frieze-like arrangements that enhance the clarity of the narrative. He paid close attention to the effects of light and atmosphere, often using a warm, somewhat diffused light to unify his scenes and create a sense of harmony. His color palette tended towards naturalistic tones, reflecting the earthy hues of the rural landscape and the simple clothing of his subjects.

To facilitate his work outdoors and capture authentic details, Mount designed and used a portable studio. This was essentially a small wooden structure on wheels, equipped with a stove and large windows, which could be hitched to a horse and moved to various locations. This allowed him to paint directly from nature or observe his subjects in their natural settings with some degree of comfort and privacy, a testament to his dedication to realism and his inventive nature.

Mount and His Contemporaries

Mount occupied a unique position within the landscape of 19th-century American art. While trained at the National Academy of Design alongside figures who would become central to the Hudson River School, his focus remained distinct. He maintained connections with the New York art world, exhibiting regularly and engaging with fellow artists. His early mentor, Henry Inman, remained a prominent figure. He also formed a close relationship with his neighbor in Stony Brook, William M. Davis, another painter whom Mount encouraged and advised, although Davis never achieved the same level of fame.

His work can be compared and contrasted with other American genre painters who emerged around the same time or slightly later. George Caleb Bingham, working primarily in Missouri, depicted scenes of frontier life, river boatmen, and political gatherings, sharing Mount's interest in American character and democracy but focusing on a different region. David Gilmour Blythe, based in Pittsburgh, offered a more satirical and often darker view of urban life and political corruption. Eastman Johnson, who studied in Europe, brought a more sophisticated technique and psychological depth to his later genre scenes, including his sensitive portrayals of African American life and New England subjects like cranberry harvests and maple sugaring.

Mount's influence also extended beyond the fine arts circle through the widespread reproduction of his paintings as engravings and lithographs. Organizations like the American Art-Union distributed prints of his work to thousands of subscribers across the country, making his images accessible to a broad middle-class audience and solidifying his status as a popular national artist. His fame even reached Europe, where prints of his paintings were circulated, contributing to a transatlantic dialogue about American culture and art.

Beyond Painting: Music, Invention, and Spiritualism

Mount's talents and interests were multifaceted. As previously mentioned, his love for music was profound. He not only played the fiddle and depicted musical scenes but also composed fiddle tunes and invented the "Cradle of Harmony" violin. This deep engagement with folk music traditions enriched his understanding of the culture he portrayed and added another dimension to his creative life.

His inventive streak wasn't limited to musical instruments. He kept detailed journals and notebooks filled with observations, sketches, and ideas on various subjects. His portable studio is another example of his practical ingenuity, designed to meet the specific needs of his artistic practice.

Later in life, Mount developed a strong interest in spiritualism, a movement that gained considerable popularity in America during the mid-19th century. His family background may have played a role, with suggestions that his father was a Freemason. Mount participated in séances and recorded experiences he believed to be communications with the spirit world in his journals. He was associated with spiritualist groups like the "Miracle Club" and reportedly believed he maintained contact with his deceased son, John. This interest in the supernatural adds another layer to the personality of an artist primarily known for his grounded depictions of everyday reality. His personal religious affiliation was Presbyterian, and his diaries also contain reflections on contemporary events, including expressing anti-Catholic sentiments regarding the causes of war.

Personal Life and Character

William Sidney Mount never married and maintained close relationships with his brothers throughout his life. His brother Henry was his early mentor, and Shepard Alonzo Mount also became a successful painter, known particularly for his still lifes. William lived for most of his adult life in the family homestead in Stony Brook, a place that clearly provided him with both personal comfort and artistic sustenance.

Accounts suggest he was a man who valued his independence and perhaps enjoyed solitude, which his rural life and portable studio allowed. Yet, his paintings reveal a keen interest in community and social interaction. He seems to have balanced a need for personal space with a deep connection to the people and activities around him. His decision to remain rooted in Long Island, rather than pursuing a more cosmopolitan career in New York City or Europe, speaks to his strong sense of place and his commitment to depicting the American life he knew best.

Later Life, Legacy, and Critical Reception

William Sidney Mount continued to paint throughout his life, though his production may have slowed in later years. He remained a respected figure in the American art world, even as artistic tastes began to shift towards the end of his career with the rise of influences from Europe, particularly the Barbizon School and Impressionism. He died in Setauket on November 19, 1868, and was buried in the Presbyterian churchyard there.

The critical reception of Mount's work has evolved over time. During his lifetime and in the decades immediately following his death, he was celebrated as a quintessential American artist, praised for his nationalism, realism, and charming depictions of rural life. His work was seen as embodying democratic ideals and capturing the wholesome character of the young nation.

By the early 20th century, as American art increasingly looked towards European modernism, Mount's style might have seemed somewhat provincial or anecdotal to some critics. However, subsequent reappraisals, particularly from the mid-20th century onwards, have reaffirmed his importance. Art historians now recognize him not only as a pioneer of American genre painting but also as a complex artist whose work engages with significant social issues, including race relations and cultural identity, albeit within the framework of his time.

His paintings are valued for their detailed documentation of 19th-century material culture, social customs, and musical traditions. His sympathetic, if imperfect, portrayal of African Americans is now seen as a crucial aspect of his legacy, offering valuable insights into the racial dynamics of the antebellum North. Artists who followed, like Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins, would push American realism in new directions, but Mount laid essential groundwork by demonstrating the artistic potential of everyday American subjects.

Today, William Sidney Mount's paintings are held in major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and The Long Island Museum of American Art, History, and Carriages, located in Stony Brook, which holds the largest single collection of his work and archives. He is remembered as a foundational figure in American art, an artist who authentically captured the life of his community and, in doing so, helped define a distinctly American artistic voice.

Conclusion

William Sidney Mount carved a unique and enduring niche in the history of American art. By turning away from prevailing academic traditions and focusing intently on the familiar world of rural Long Island, he became a master chronicler of everyday life in the young republic. His paintings, filled with narrative detail, gentle humor, and keen social observation, captured the spirit of his time and place. His interest in music, his inventive spirit, and his pioneering efforts to depict African Americans with greater dignity further enrich his legacy. More than just charming scenes of country life, Mount's works offer a valuable window into the culture, social dynamics, and burgeoning identity of 19th-century America, securing his place as one of the nation's most important early genre painters.