Joseph Denovan Adam stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century Scottish art. Renowned primarily for his evocative depictions of the Scottish Highlands, its rugged scenery, and particularly its iconic Highland cattle, Adam carved a niche for himself as a master of animal painting and landscape. His work captured the spirit of rural Scotland during a period of intense national identity exploration, blending keen observation with a palpable affection for his subjects. Born into an artistic family, his career trajectory took him from Glasgow to London and back, culminating in widespread recognition both at home and abroad.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Joseph Denovan Adam was born in Glasgow on September 19, 1842. His artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age, heavily influenced by his father, Joseph Adam (Senior), who was himself a landscape painter. The elder Adam provided his son with his initial training, instilling a foundation in the principles of observation and draughtsmanship. Seeking broader opportunities and exposure, the Adam family relocated to London when Joseph Denovan was a boy, a move driven by the father's professional aspirations.

This relocation proved pivotal for the young artist's development. In London, Joseph Denovan Adam furthered his formal art education by enrolling in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. This institution was the epicentre of artistic training in Britain, exposing students to rigorous academic practices and the works of established masters. Alongside his studies at the RA Schools, Adam actively participated in life drawing and sketching sessions, including those at the Langham Sketching Club, a well-known hub for artists to hone their skills through rapid composition exercises. This combination of paternal guidance, formal academic training, and practical sketching experience equipped him with a versatile skill set.

His early career began to take shape in London during the 1860s. He started exhibiting his oil paintings, initially gaining exposure through the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions. These early works already hinted at his burgeoning interest in landscape and animal subjects, themes that would come to dominate his oeuvre. The London art scene, bustling and competitive, provided a challenging yet stimulating environment for the young painter to establish his voice.

Return to Scotland and Stylistic Development

Despite his beginnings in the London art world, the pull of his native Scotland proved strong. Joseph Denovan Adam eventually returned, establishing his practice more firmly within the Scottish artistic milieu. This return coincided with a crystallisation of his artistic focus. He became increasingly dedicated to capturing the unique character of the Scottish Highlands – its dramatic landscapes, changeable weather, and the agricultural life that defined its rural communities.

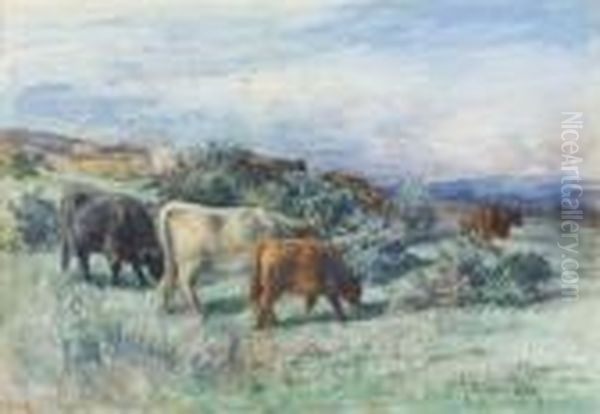

His style evolved towards a robust naturalism, marked by careful attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of animal anatomy and textures. He developed a remarkable ability to depict Highland cattle, not merely as generic livestock, but as individuals possessing distinct characters. His paintings often feature these animals prominently within their natural environment, showcasing their resilience against the backdrop of misty glens, rocky outcrops, or tranquil lochs. His handling of light and atmosphere became increasingly adept, capturing the specific qualities of the Highland air and the interplay of sun and shadow across the landscape.

While contemporaries like Horatio McCulloch also specialised in grand Highland vistas, Adam's focus often zoomed in, giving precedence to the animals and the immediate environment. His work differed significantly from the tighter, more anecdotal animal paintings of Sir Edwin Landseer, though Landseer's immense popularity undoubtedly contributed to the public appetite for animal subjects during the Victorian era. Adam's approach felt more direct, less anthropomorphised, grounded in the observation of farm life and the natural behaviour of the animals.

The Highland Cattle: A Signature Subject

The Highland cow, with its shaggy coat, imposing horns, and stoic demeanour, became Joseph Denovan Adam's most recognisable motif. His dedication to this subject elevated him to become one of the foremost painters of Highland cattle in the late Victorian period. These animals were more than just picturesque elements; they symbolised the wildness and hardiness associated with the Scottish Highlands, embodying a sense of untamed nature intertwined with pastoral life.

Adam's depictions were notable for their authenticity. He spent considerable time observing the cattle, understanding their movements, social interactions, and relationship with the landscape. This deep familiarity allowed him to portray them with convincing realism and empathy. Whether depicting a solitary bull standing sentinel on a hillside, a herd fording a stream, or cattle resting peacefully in a pasture, his paintings convey a sense of weight, texture, and presence. The rough, weather-beaten coats, the glint of light in their eyes, and the surrounding vegetation were all rendered with meticulous care.

His focus on cattle places him within a broader European tradition of animal painting. Artists like the French painter Rosa Bonheur had achieved international fame for their powerful depictions of animals, particularly horses and cattle, demonstrating that animal subjects could be treated with seriousness and artistic ambition. Similarly, painters of the Barbizon School, such as Constant Troyon, integrated realistic portrayals of livestock into their landscape compositions, influencing generations of artists. Adam's work, while distinctly Scottish, resonates with this wider interest in rural life and animal portraiture.

Career Success and Recognition

Joseph Denovan Adam's commitment to his chosen subjects brought him considerable success and recognition throughout his career. He became a regular exhibitor at major institutions, not only the Royal Academy in London but also prominent Scottish venues like the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh and the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts (RGIFA). His work consistently found favour with both the public and critics.

His growing reputation was solidified by his election to prestigious artistic bodies. In 1882, he was elected to the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour (RSW), becoming a full member in 1884. That same year, 1884, marked his election as an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy (ARSA), a significant honour confirming his standing within the Scottish art establishment. These memberships placed him alongside other leading Scottish artists of the day, such as the landscape painters Peter Graham and John MacWhirter, who also enjoyed widespread popularity for their Highland scenes.

Adam's renown extended beyond British shores. He exhibited works internationally, including at the Paris Salon, the premier art exhibition in France. His participation culminated in a notable success in 1894 when he was awarded a gold medal at the Salon. Further international recognition came in 1895 when the French government purchased one of his paintings for the state collection (likely the Musée du Luxembourg at the time), a significant mark of esteem for a foreign artist. These accolades underscored the appeal of his distinctly Scottish subject matter and his technical proficiency to a wider European audience.

The Educator: The Craigmillar School and Byre Studio

Beyond his personal artistic practice, Joseph Denovan Adam made a notable contribution to art education in Scotland. Around 1887, he moved to Craigmill Lodge, near Stirling, a location that offered easy access to the Highland scenery he loved. Here, he established a school dedicated to animal painting and landscape, attracting students not just from Scotland but from across Britain and even continental Europe.

A unique feature of his educational approach was the emphasis on direct observation and working en plein air (outdoors), supplemented by dedicated studio facilities. He famously constructed a large glass-walled studio, known as the "Byre Studio," which allowed students to paint animals from life regardless of the often-inclement Scottish weather. This innovative setup provided shelter while maintaining optimal natural light. Furthermore, the school kept various animals, including dogs and different breeds of livestock, specifically for students to use as models.

This hands-on approach, combining studio work with outdoor sketching and readily available animal models, offered a practical and immersive learning experience. It reflected Adam's own commitment to realism based on close study. The school became a hub for aspiring animal and landscape painters, fostering a community of artists focused on these genres. His role as an educator demonstrated a desire to pass on his skills and passion, contributing to the continuation of representational painting traditions in Scotland.

Artistic Context and Connections

Joseph Denovan Adam's career unfolded during the latter half of the Victorian era, a period characterised by diverse artistic trends and a strong public interest in narrative, landscape, and genre painting. While academic realism remained dominant, movements like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with figures such as John Everett Millais, had earlier challenged conventions, and new approaches to landscape painting were emerging, partly influenced by French developments.

Adam's work sits firmly within the tradition of British landscape and animal painting, tracing a lineage back to earlier masters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, who had revolutionised the depiction of nature. However, his specific focus on Scottish Highland subjects aligned him with a strong national school of landscape painting that flourished in the 19th century, celebrating Scotland's distinct identity and scenery. Artists like McCulloch, Graham, and MacWhirter were key figures in this movement.

While Adam maintained a broadly realistic style, his work was largely untouched by the more radical stylistic innovations emerging towards the end of the century, such as Impressionism or the burgeoning Glasgow School (the "Glasgow Boys," including James Guthrie and E.A. Walton), whose focus was more on tonal values, contemporary social realism, or decorative effects. Adam remained committed to detailed representation and the specific character of the Highland landscape and its fauna, catering to a taste for recognisable and evocative scenes. His connection to his father, Joseph Adam Sr., represents a direct familial artistic lineage, common in previous centuries but becoming less frequent by the late 19th century.

Later Years and Legacy

In the later stages of his life, Joseph Denovan Adam faced health challenges. Suffering from rheumatism, he found the rural environment of Craigmill increasingly difficult and eventually relocated back to Glasgow. Despite his illness, he continued to paint, although some accounts suggest his later work occasionally lacked the consistent vigour of his prime years. Nevertheless, his fundamental skills and understanding of his subjects remained apparent.

His productive career was cut relatively short. Joseph Denovan Adam passed away at his home in Glasgow on April 22, 1896, at the age of 54. Despite his premature death, he left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its faithful and atmospheric portrayal of Scotland.

Today, Joseph Denovan Adam is remembered as one of Scotland's most accomplished animal and landscape painters of the Victorian era. His specialisation in Highland cattle created a lasting visual iconography associated with the region. His paintings are held in numerous public collections across the United Kingdom, with Art UK listing over 20 works in national and regional galleries, ensuring his contribution remains accessible. While perhaps not an innovator in the mould of avant-garde movements, his dedication to his craft, his skill in capturing the essence of the Scottish Highlands, and his role as an educator secure his place in British art history.

Conclusion

Joseph Denovan Adam's artistic journey was one of dedication to the landscapes and wildlife of his native Scotland. From his early training under his father and at the Royal Academy Schools to his established career as a celebrated painter of Highland scenes and cattle, he developed a distinctive and highly regarded style. His work resonated with the Victorian public's appreciation for naturalism and evocative depictions of rural life. Through his popular paintings and his influential teaching practice near Stirling, Adam made a significant and lasting contribution to Scottish art, leaving behind a legacy rich in atmospheric landscapes and masterful animal studies, particularly his iconic portrayals of Highland cattle that continue to define our image of the rugged beauty of Scotland.