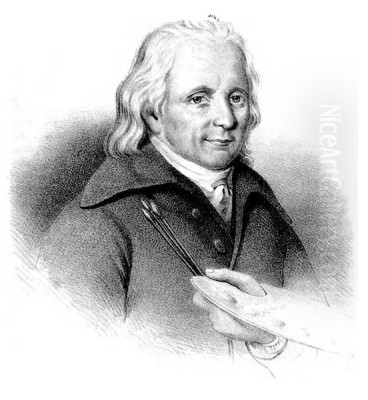

Elias Martin stands as a seminal figure in the history of Swedish art, celebrated primarily for his contributions to landscape painting during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Born in Stockholm in 1739 and passing away there in 1818, Martin's life spanned a period of significant cultural and artistic development in Sweden, often referred to as the Gustavian era. He was not only a painter but also a skilled engraver and printmaker, whose work captured the changing face of both urban and rural Sweden, as well as scenes from his influential time spent abroad, particularly in England. His ability to blend topographical accuracy with emerging Romantic sensibilities marked him as a transitional figure and earned him the reputation as Sweden's "first great landscape painter."

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Elias Martin was born into a milieu of craftsmanship and artistry. His father, Olof Martin, was a master carpenter (or cabinetmaker, ébéniste), suggesting a family environment where skill, design, and materials were understood and valued. This background likely provided Elias with an early, practical exposure to visual and structural forms. He received his initial training within his father's workshop, a common starting point for artisans' sons at the time. This foundational experience may have instilled in him a respect for meticulous work and attention to detail, qualities evident even in his later, more atmospheric landscapes.

His formal artistic education began under the guidance of Carl Friedrich Schultz, a painter associated with the court. Schultz introduced Martin to the world of decorative painting, a field that often involved creating large-scale works for interiors, including landscapes and architectural views. Through Schultz, Martin gained exposure to the interiors and surrounding views of significant Stockholm landmarks like the Royal Palace and Drottningholm Palace. This early focus on specific locations and decorative schemes likely honed his skills in observation and representation, laying the groundwork for his later specialization in topographical and landscape art.

Seeking broader horizons and more advanced training, Martin, like many aspiring artists of his generation, looked beyond Sweden's borders. The traditional artistic pilgrimage often led south to Italy, but Martin's path initially took him elsewhere, reflecting the shifting centres of artistic influence in 18th-century Europe.

The London Years: Exposure and Recognition

Around 1768, Elias Martin travelled to London, a burgeoning metropolis and a vibrant centre for the arts and commerce. This move proved pivotal for his career. In London, he became associated with the "Swedish Circle of Emigres," a group of expatriate Swedes who supported each other professionally and socially. A key figure in this circle, and a significant contact for Martin, was Sir William Chambers, the prominent architect of Swedish descent who enjoyed royal patronage in Britain. This connection likely opened doors for Martin within London's artistic and social scenes.

During his time in England, which lasted until 1780, Martin absorbed the prevailing trends in British art, particularly the flourishing school of landscape painting and watercolour technique. Artists like Paul Sandby, often called the "father of English watercolour," and Richard Wilson, with his classically inspired landscapes, were shaping the British taste. Martin was exposed to their work and the broader appreciation for picturesque scenery and topographical views. He adapted his style, incorporating the lighter palettes and atmospheric effects characteristic of English watercolour, while also continuing to work in oils.

His talent gained recognition, culminating in his election as an Associate of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1771. This was a significant honour for a foreign artist and testified to his standing within the competitive London art world. During this period, he produced numerous views of English estates, parks, and landmarks. A notable example is his painting Pope's Villa at Twickenham (1773), depicting the famous residence of the poet Alexander Pope, showcasing his skill in rendering architecture within a carefully observed landscape setting. His English works often combined detailed topographical information with a sensitivity to light and atmosphere that prefigured Romanticism.

Return to Sweden and Mature Style

Upon his return to Sweden in 1780, Elias Martin brought back the techniques, styles, and prestige acquired during his twelve years in London. He was welcomed back as an established artist of international repute. He became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (Konstakademien) in Stockholm and was later appointed a professor there, solidifying his position within the Swedish art establishment.

His mature style represented a synthesis of his Swedish roots and his English experiences. He became the foremost interpreter of the Swedish landscape, applying his refined watercolour and oil techniques to depict his native scenery. His subjects ranged from panoramic views of Stockholm and other cities to depictions of rural estates, waterfalls, and scenes of daily life. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the specific character of the Swedish light and atmosphere, often imbuing his landscapes with a sense of tranquility and poetic charm.

Martin's work often balanced objective documentation with subjective interpretation. His topographical views, such as the View of Stockholm (1801), provided valuable records of the city's appearance at the turn of the century, yet they were more than mere records. He carefully composed his scenes, often employing elevated viewpoints and paying close attention to the play of light and shadow across buildings, water, and foliage, creating visually engaging and emotionally resonant images.

Artistic Techniques and Influences

Elias Martin was proficient in both oil painting and watercolour, but he is particularly celebrated for his mastery of the latter. His time in England coincided with a period of great innovation in watercolour painting, and he embraced its potential for capturing subtle atmospheric effects and luminous transparency. His watercolours are characterized by delicate washes, fine linework, and a sophisticated use of colour to suggest depth and mood.

In his oil paintings, Martin often employed a similar sensitivity to light, though with the richer textures and deeper tones afforded by the medium. His landscapes frequently feature prominent skies, with carefully rendered cloud formations and effects of sunlight or twilight, contributing significantly to the overall atmosphere of the work. This focus on light aligns him with the broader European trend towards Romanticism, where nature was increasingly seen as a source of emotional and spiritual experience.

His influences were diverse. The Dutch landscape tradition of the 17th century, with its emphasis on realism and atmospheric perspective, provided a foundational model. French landscape painters like Claude Lorrain, known for idealized, light-filled compositions, also left their mark, particularly in the harmonious arrangement of elements in Martin's scenes. Crucially, the British school, including figures like Sandby and Wilson, and the general aesthetic of the Picturesque, shaped his approach during his formative London years. He successfully integrated these various influences into a personal style that resonated with Swedish sensibilities.

Martin also worked as an engraver and printmaker, often creating aquatints based on his own paintings and drawings. This allowed for wider dissemination of his views and contributed to the growing public interest in Swedish scenery. His prints, like his paintings, are valued for their technical skill and artistic merit.

Representative Works and Themes

Elias Martin's oeuvre encompasses a wide range of subjects, though landscapes and cityscapes dominate. Several works stand out as representative of his style and concerns:

Pope's Villa at Twickenham (1773): A key work from his London period, demonstrating his skill in topographical rendering combined with the picturesque aesthetic popular in England.

View of Rome (1787): Although primarily known for Swedish and English scenes, Martin also travelled. This view indicates his engagement with the classical tradition and the Grand Tour destinations favoured by artists, likely painted after a trip or based on sketches and other artists' work. It showcases his ability to handle grand architectural subjects within an expansive landscape.

Älvkarleby Waterfall: Martin depicted several Swedish natural landmarks. His views of waterfalls like Älvkarleby capture the power and beauty of nature, themes increasingly explored by Romantic artists. He balances the wildness of the scene with a sense of compositional order.

View of Stockholm (e.g., 1801): Martin produced numerous views of the Swedish capital from various vantage points, documenting its growth and character. These works are invaluable historical records, rendered with his characteristic attention to light, water, and architectural detail.

The Ebonists (or similar genre scenes): While less common than his landscapes, Martin occasionally depicted scenes related to crafts or daily life, perhaps reflecting his own family background in carpentry/cabinetmaking. These works offer glimpses into the social fabric of the time.

His themes often revolved around the harmony between human activity and the natural environment. Buildings nestle comfortably within landscapes, cities are shown in relation to their surrounding waters and hills, and figures often appear as small elements within a larger natural setting, suggesting a balanced, ordered world, albeit one touched by the burgeoning sensitivity of Romanticism.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Elias Martin worked during a vibrant period in Swedish art history, the Gustavian era, named after King Gustav III, a great patron of the arts. He was part of a talented generation of artists who contributed to Sweden's cultural flourishing. Among his notable contemporaries were:

Johan Tobias Sergel (1740-1814): Sweden's most celebrated sculptor of the era, known for his Neoclassical style, influenced by his time in Rome. Sergel and Martin represented the leading figures in sculpture and landscape painting, respectively.

Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816): A painter known for his detailed interior scenes depicting both aristocratic and bourgeois life, as well as industrial settings. His genre paintings offer a complementary view of Gustavian society.

Alexander Roslin (1718-1793): An internationally successful portrait painter, primarily active in Paris, renowned for his exquisite rendering of fabrics and likenesses.

Carl Fredrik von Breda (1759-1818): A prominent portrait painter who studied under Reynolds in London and brought a British-influenced style back to Sweden. He and Martin both benefited from time in England.

Nils Lafrensen the Younger (1737-1807): Known for his delicate gouache miniatures, often depicting elegant social scenes, primarily working in Paris.

Gustaf Lundberg (1695-1786): A master of pastel portraiture, active earlier but whose career overlapped with Martin's formative years.

Jean Eric Rehn (1717-1793): An architect, designer, and engraver who played a significant role in establishing the Neoclassical style in Swedish decorative arts.

Lorens Pasch the Younger (1733-1805): A respected portrait painter, particularly known for his official portraits of royalty and aristocracy.

Louis Masreliez (1748-1810): An important interior designer and painter who brought Italian Neoclassical influences (especially from Pompeii) to Swedish interiors.

Carl Gustaf Pilo (1711-1793): A leading portrait painter, primarily active in Denmark before returning to Sweden to become director of the Academy.

In England, Martin's contemporaries in landscape included Paul Sandby, Richard Wilson, Thomas Gainsborough (in his landscape work), William Marlow, and the emerging J.M.W. Turner. His association with the architect Sir William Chambers was also significant. Martin navigated these Swedish and British artistic contexts, absorbing influences while forging his own distinct path. He was less revolutionary than Sergel in sculpture, perhaps, but equally important in establishing landscape as a major genre in Swedish art.

Teaching and Other Activities

Beyond his own painting and printmaking, Elias Martin contributed to the arts as an educator. His appointment as a professor at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts involved teaching drawing and perspective. While specific records of his students are scarce, his position suggests he influenced a generation of younger artists. One documented instance of his teaching involved instructing August Ehrensvärd, a military commander and architect involved in the construction of the Suomenlinna fortress, indicating the breadth of his connections and the perceived value of artistic skills even outside purely artistic circles.

Martin also reportedly engaged in decorative work, including designs for ship decoration. This aligns with his early training under Schultz and the broader role of artists in the 18th century, who often worked across different fields, from easel painting to decorative schemes and design.

Legacy and Significance

Elias Martin's primary legacy lies in his elevation of landscape painting within Swedish art. Before him, landscape was often considered a secondary genre or primarily served decorative purposes. Martin, equipped with international experience and academic recognition, treated landscape with seriousness and sensitivity, paving the way for later generations of Swedish landscape painters in the 19th century.

His extensive documentation of Stockholm and Swedish scenery provides invaluable historical insight. His works capture the transition from the Gustavian era to the early 19th century, reflecting changes in both the physical environment and artistic sensibilities. His mastery of watercolour technique was particularly influential, demonstrating the medium's potential for capturing the nuances of the Nordic landscape.

While perhaps not as dramatically innovative as some of his European contemporaries who were pushing towards full-blown Romanticism, Martin's art represents a crucial bridge. He combined the clarity and order associated with Neoclassicism and topographical traditions with a growing appreciation for atmospheric effects, picturesque compositions, and the specific character of place. He remains a highly regarded figure, whose works are held in major collections in Sweden, such as the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm and the Gothenburg Museum of Art, as well as internationally, including in Britain where he spent a significant part of his career.

Conclusion

Elias Martin was a multifaceted artist – painter, engraver, printmaker, and teacher – who played a pivotal role in the development of Swedish art. His journey from a Stockholm artisan's workshop to the Royal Academy in London and back to a professorship in Stockholm reflects a career marked by ambition, skill, and adaptability. He skillfully synthesized Swedish traditions with dominant European trends, particularly those of the British landscape school. Through his numerous views of Sweden and England, rendered with technical finesse and a subtle poetic sensibility, Elias Martin not only documented his times but also fundamentally shaped the appreciation and practice of landscape painting in Sweden, securing his place as one of the nation's most important 18th-century artists.