Introduction: A Painter of Light and Landscape

Emile Charles Lambinet (1815-1877) stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French landscape painting. Born in the historic town of Versailles on December 13, 1815, and passing away in Bougival on January 27, 1877, Lambinet dedicated his artistic career to capturing the serene beauty and tranquil rhythms of rural France. Though often associated with the Barbizon School due to his stylistic affinities and commitment to naturalism, he forged his own path, creating works celebrated for their luminous quality, meticulous observation, and gentle, evocative charm. His paintings offer idyllic glimpses into the fields, riverbanks, and village outskirts of the Île-de-France region, rendered with a sensitivity to light and atmosphere that continues to resonate with viewers today.

Lambinet emerged during a period of profound transformation in French art, as the dominance of Neoclassical history painting began to wane, giving way to a growing interest in realism and the direct observation of nature. He navigated this changing landscape skillfully, absorbing lessons from esteemed masters while developing a distinct voice. His consistent participation in the prestigious Paris Salon and the accolades he received, including the Legion of Honour, attest to the respect he commanded within the art establishment of his time. His legacy endures not only through his beautiful canvases, housed in museums worldwide, but also through his influence on subsequent artists and his contribution to the enduring tradition of French landscape painting.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Versailles

Emile Lambinet's artistic journey began in Versailles, the opulent seat of former royal power, whose surrounding parks and countryside would provide early inspiration. Growing up in such an environment likely instilled in him an appreciation for both formal garden landscapes and the less tamed nature that lay beyond the palace grounds. His formal artistic education commenced under the tutelage of masters who represented different facets of the French art scene.

One of his most influential teachers was Horace Vernet (1789-1863), a towering figure known primarily for his large-scale historical and battle paintings, as well as Orientalist scenes. While Vernet's subject matter might seem distant from Lambinet's eventual focus, study under such a prominent and technically proficient artist would have provided a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the professional demands of the art world. Vernet himself occasionally painted landscapes, and his emphasis on accuracy and detail may have left an imprint on Lambinet's careful rendering of the natural world.

Perhaps even more pivotal was Lambinet's relationship with Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875). Corot was a central figure in the development of French landscape painting, acting as a bridge between the Neoclassical tradition and the burgeoning movements of Realism and Impressionism. Corot's emphasis on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere en plein air (outdoors), combined with his poetic sensibility and often silvery tonalities, profoundly shaped Lambinet's approach. The clarity of light, the harmonious compositions, and the subtle gradations of tone found in Lambinet's work owe a significant debt to Corot's example. Lambinet is also noted to have studied briefly with Antoine Félix Boisselier (1790-1857), a landscape painter who himself had studied under Jean-Victor Bertin, a proponent of the historical landscape tradition, further grounding Lambinet in the established practices of the genre.

The Spirit of Barbizon: Naturalism and Plein Air

While Emile Lambinet did not reside in the village of Barbizon or the nearby Forest of Fontainebleau, the heartland of the eponymous school, his artistic philosophy and style align closely with the Barbizon movement's core tenets. The Barbizon School, flourishing roughly from the 1830s to the 1870s, represented a significant shift towards naturalism in landscape painting. Artists associated with this movement rejected the idealized, historical landscapes favored by the Academy and instead sought to depict rural scenery with truthfulness and directness, often working from sketches made outdoors.

Key figures of the Barbizon School included Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867), often considered its leader, known for his detailed and sometimes somber depictions of the Forest of Fontainebleau; Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), who focused on portraying the dignity and hardship of peasant life within the landscape; Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), celebrated for his river scenes and his innovative use of a studio boat to capture waterside views directly; Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña (1807-1876), known for his richly textured forest interiors and mythological scenes; Constant Troyon (1810-1865), who specialized in landscapes featuring cattle; and Jules Dupré (1811-1889), whose works often conveyed a more dramatic and turbulent vision of nature.

Lambinet shared their commitment to observing nature firsthand and rendering it without excessive idealization. His paintings, like those of his Barbizon contemporaries, often feature humble rural subjects – quiet riverbanks, country paths, farm workers, and village edges. He embraced the practice of sketching outdoors to capture the immediate impressions of light and atmosphere, even if the final canvases were often completed in the studio. His connection lies firmly in this shared spirit of realism and the elevation of the everyday French landscape as a worthy subject for serious art, moving away from classical or mythological pretexts.

Artistic Style: Clarity, Light, and Atmosphere

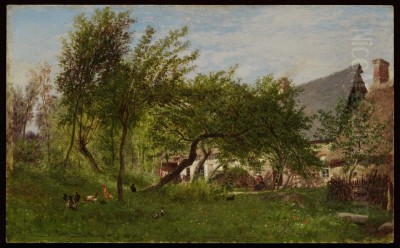

Emile Lambinet's style is characterized by a harmonious blend of careful observation and a gentle, poetic sensibility. His paintings are often bathed in a clear, luminous light, typically depicting pleasant weather conditions – sunny days or softly overcast skies. Unlike the later Impressionists who would dissolve form in light, Lambinet maintained a strong sense of structure and detail in his compositions, reflecting his training and perhaps the influence of Vernet.

His compositions are typically well-balanced and serene, often employing established landscape conventions like receding diagonals (paths, rivers) to create depth, framed by trees or foliage. However, there is a naturalness and lack of contrivance in his arrangements that feels authentic to the scenes depicted. He possessed a keen eye for the specific textures of the landscape – the rough bark of trees, the varied greens of foliage, the reflective surface of water, the soil of a country lane.

Lambinet's palette is often described as fresh and appealing, favoring silvery greens, soft blues for skies and water, and warm earth tones. His application of paint could be fluid and relatively thin in passages, contributing to the sense of light and air, yet he built up sufficient detail to give substance and definition to objects. He excelled at capturing atmospheric perspective, rendering distant elements with softer focus and cooler tones to enhance the illusion of space. His brushwork, while not as broken or visibly energetic as that of the Impressionists, was often lively enough to convey the vibrancy of nature.

Key Themes: The Idyllic French Countryside

The primary subject of Lambinet's art was the landscape of the Île-de-France region, particularly the areas around Versailles, Bougival, and Ecouen where he lived and worked. He was drawn to the gentle, cultivated beauty of this region rather than dramatic mountain scenery or wild coastlines. His paintings frequently depict tranquil riverbanks, often featuring the Seine or its tributaries. These scenes commonly include figures engaged in quiet activities, such as fishing, boating, or, very characteristically, women washing clothes (lavandières) by the water's edge.

Country roads and paths winding through fields or woods are another recurring motif, inviting the viewer into the landscape. He often painted village scenes, focusing on the outskirts where cottages meet fields or rivers, capturing the peaceful coexistence of human habitation and nature. Figures, when included, are typically small in scale relative to the landscape, emphasizing the dominance of the natural setting. They are often depicted as peasants or rural folk going about their daily tasks, integrated harmoniously into their environment rather than serving as the primary focus or conveying a strong social message in the manner of Millet.

Lambinet's vision of the French countryside is predominantly idyllic and peaceful. His works evoke a sense of calm, order, and gentle beauty. They represent a nostalgic appreciation for rural life and the simple pleasures of nature, offering a respite from the increasing industrialization and urbanization of France during the 19th century. This appealing quality contributed significantly to his popularity during his lifetime and continues to attract admirers.

Representative Works: Capturing Rural Life

Several paintings exemplify Emile Lambinet's characteristic style and subject matter. His depictions of Lavandières (Washerwomen) are particularly well-known. In works like Women Washing Clothes, he presents a scene of communal female labor by a riverbank. The figures are rendered with care but remain integrated within the larger landscape composition. The focus is often on the play of light on the water, the reflections of trees and sky, and the overall atmosphere of a working day outdoors. The colors are typically fresh and naturalistic, and the composition balances the human activity with the surrounding natural elements.

Bord de rivière (River Bank) is a title applicable to many of his works, highlighting his fondness for waterside scenes. These paintings often feature calm stretches of river, lined with trees whose foliage is meticulously rendered. Reflections in the water are a key element, handled with skill to convey the stillness or gentle movement of the surface. Sometimes a small boat, a fisherman, or distant buildings add points of interest, but the dominant impression is one of tranquility and the quiet beauty of the riverine environment.

Landscape with Workers in a Field showcases another common theme. Here, Lambinet depicts agricultural activity within a broad landscape setting. Figures might be shown harvesting, tending animals, or simply resting. As with his other works, the figures are part of the scene rather than its sole subject. The emphasis is on the expanse of the fields, the quality of the light falling across the land, and the harmonious relationship between humanity and nature in a rural context. The detailed rendering of the foreground often contrasts with a softer treatment of the distant background, enhancing the sense of depth. Other notable works include views of Bougival, paths through wooded areas, and various scenes capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the Île-de-France.

Salon Success and Official Recognition

Emile Lambinet was a consistent and successful participant in the official Paris Salon, the most important art exhibition in France during the 19th century. Acceptance and recognition at the Salon were crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success. Lambinet began exhibiting there as early as 1833 and continued to do so regularly throughout his career, reportedly until 1878 (though this date extends slightly beyond his death in late 1877 or early 1878, suggesting works may have been submitted posthumously or the timeframe refers to his active exhibiting years).

His talent was recognized with several awards at the Salon. He received medals in 1843 (Third Class), 1853 (Second Class), and 1857 (First Class recall, or possibly another Second Class medal – sources vary slightly but confirm multiple awards). These accolades demonstrate that his style, while rooted in the naturalism associated with the Barbizon group (which sometimes faced resistance from the conservative Salon jury), was also appreciated for its technical skill, pleasing compositions, and appealing subject matter.

The culmination of his official recognition came in 1867, when he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour (Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur). This prestigious award, established by Napoleon Bonaparte, was a significant mark of distinction conferred by the French state for outstanding contributions in various fields, including the arts. Receiving the Legion of Honour solidified Lambinet's status as a respected and established figure within the French art world. His success at the Salon indicates his ability to appeal both to official taste and to the growing public interest in landscape painting.

Life in Bougival and the Artistic Hub of Ecouen

While born and initially based in Versailles, Lambinet spent a significant portion of his later working life in Bougival, a town situated on the Seine river to the west of Paris. He moved there around 1860 and remained associated with the area until his death. Bougival, with its picturesque river views and surrounding countryside, was becoming increasingly popular among artists during this period. Its proximity to Paris made it accessible, yet it offered the tranquil rural subjects that landscape painters sought.

The presence of artists in Bougival would intensify in the following decades, with Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and Alfred Sisley (1839-1899) famously capturing its scenery, particularly the boating and leisure activities at La Grenouillère nearby. Lambinet's earlier presence there places him among the artists who recognized the pictorial potential of these Seine-side locations before the Impressionist wave. His paintings of Bougival capture the quieter, more pastoral aspects of the town and its environs.

Lambinet also regularly visited and painted in Ecouen, another town north of Paris that became a significant artists' colony in the mid-19th century. Ecouen attracted numerous painters, including figures associated with academic realism as well as landscape artists. Lambinet's presence there suggests his engagement with these artistic communities, providing opportunities for exchange and inspiration. His connection to specific locales like Bougival and Ecouen underscores his commitment to painting directly from nature in the areas he knew well.

Connections, Contemporaries, and Influence

Emile Lambinet's artistic journey was interwoven with connections to numerous other painters, both as teachers, contemporaries, and even students. His foundational training under Horace Vernet and, more crucially, Camille Corot, set the stage for his development. Corot, in particular, remained a guiding light for many landscape painters of Lambinet's generation and beyond.

His stylistic kinship with the Barbizon painters – Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, Constant Troyon, Jules Dupré – places him firmly within the major movement towards naturalism in French landscape art. He shared their dedication to depicting the French countryside with sincerity. Daubigny's river scenes, often painted from his boat studio "Le Botin," offer an interesting comparison to Lambinet's own numerous riverbank views, though Lambinet's approach generally retained more detailed finish.

Looking at precursors, the work of artists like Georges Michel (1763-1843), who painted dramatic views of the Montmartre environs with expressive brushwork, foreshadowed the interest in local landscape. Lambinet's contemporaries also included artists who paved the way for Impressionism, such as Eugène Boudin (1824-1898) and the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819-1891). Both Boudin and Jongkind were masters at capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, particularly in coastal and river scenes, and their work influenced the younger Impressionists. While Lambinet's style remained distinct, he worked alongside these currents of innovation.

Lambinet also played a role as a teacher or mentor. Notably, the American painter Frank Henry Shapley (1842-1906) studied with Lambinet in Paris during his European travels in 1867-1868. Shapley went on to become known for his landscapes, particularly scenes of the White Mountains in New Hampshire, and his time with Lambinet likely reinforced his skills in landscape composition and observation. This connection highlights Lambinet's standing and influence extending even to international artists seeking training in Paris.

Legacy and Collections: Enduring Appeal

Emile Charles Lambinet left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill and serene beauty. His paintings found favor with collectors during his lifetime, and his reputation has endured, securing his place as a respected, if sometimes overlooked, master of 19th-century French landscape.

A significant part of his legacy is preserved in the Musée Lambinet in his hometown of Versailles. This municipal museum, housed in an elegant 18th-century building, owes its existence to a bequest from Victor Lambinet, a cousin of the painter. While the museum's collections cover the history of Versailles more broadly, it holds a number of Emile Lambinet's works, serving as a key repository for understanding his art in the context of his origins.

Beyond Versailles, Lambinet's paintings are held in numerous public collections across Europe and North America. Institutions such as the National Gallery of Ireland (Dublin), the Glasgow Art Galleries, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, the Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam), and museums in Antwerp and Bougival are listed among those holding his works. Major international museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery in London also include examples of his paintings, attesting to his widespread recognition and the enduring appeal of his gentle, light-filled landscapes.

His influence can be seen in the continuation of the Barbizon tradition by other artists and in the training he provided to students like Shapley. Lambinet represents a successful assimilation of the Barbizon ethos of naturalism and plein air study into a style that was both personally expressive and acceptable to the Salon establishment, contributing significantly to the popularity and development of landscape painting in France.

Conclusion: A Gentle Vision of Nature

Emile Charles Lambinet carved a distinct niche for himself within the vibrant landscape of 19th-century French art. Guided by the influential teachings of Corot and Vernet, and inspired by the naturalist spirit of the Barbizon School, he developed a style characterized by luminous clarity, careful composition, and a deep affection for the countryside of the Île-de-France. His paintings of tranquil riverbanks, sunlit fields, and quiet village scenes offer a peaceful and idyllic vision of rural life.

Through consistent exhibition at the Paris Salon, multiple awards, and the prestigious Legion of Honour, Lambinet achieved significant recognition during his lifetime. His work resonated with a public increasingly drawn to depictions of nature and the perceived simplicity of country living. While perhaps lacking the revolutionary impact of the Impressionists who followed, Lambinet's contribution lies in his mastery of light and atmosphere, his sensitive rendering of specific locales like Bougival and Ecouen, and his role in popularizing a gentle, accessible form of landscape realism. His paintings remain a testament to his skill and provide enduring glimpses into the serene beauty of the French countryside as seen through the eyes of a dedicated and accomplished artist.