Constant Troyon stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century French art. Born in Sèvres on August 28, 1810, and passing away in Paris on February 21, 1865, Troyon carved a unique niche for himself, primarily associated with the Barbizon School. While initially known for his landscapes, he achieved enduring fame as one of the preeminent animal painters, or animaliers, of his era. His canvases, often depicting cattle and sheep bathed in the soft light of the French countryside, captured a sense of pastoral realism that resonated deeply with contemporary audiences and continues to be admired today. His journey from porcelain decorator to internationally acclaimed painter reflects both personal dedication and the shifting artistic currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Troyon's artistic beginnings were rooted in the decorative arts, a foundation that arguably informed his later sensitivity to detail and composition. His father worked as a decorator at the renowned Sèvres porcelain manufactory, immersing the young Constant in an environment where craftsmanship and aesthetic precision were paramount. Following in his father's footsteps, Troyon initially pursued a career as a porcelain painter, receiving early instruction from Denis-Désiré Riocreux, himself a painter associated with the Sèvres factory. This training honed his skills in meticulous rendering and the application of colour.

However, the allure of landscape painting soon beckoned. By the age of 21, Troyon decided to dedicate himself fully to painting on canvas, moving beyond the confines of porcelain decoration. His early explorations focused on capturing the natural world directly, often working en plein air (outdoors), a practice gaining traction among progressive artists seeking authenticity beyond academic conventions. This period saw him travelling and sketching in the regions surrounding Paris, developing his observational skills and his ability to translate the nuances of light and atmosphere onto canvas.

A crucial connection during this formative period was his friendship with Camille Roqueplan, an established painter who introduced Troyon to a circle of artists who would profoundly shape his trajectory. Through Roqueplan, Troyon encountered key figures associated with what would become known as the Barbizon School, artists who shared his burgeoning interest in direct observation and the unadorned beauty of the French landscape. This network provided both artistic stimulus and camaraderie, setting the stage for his deeper engagement with landscape painting.

Embracing the Landscape: The Barbizon Connection

The Barbizon School was less a formal institution with a rigid doctrine and more a loose affiliation of artists drawn together by a shared philosophy. Centered around the village of Barbizon, nestled on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau near Paris, these painters rejected the Neoclassical ideals and historical subjects favoured by the official French Academy. Instead, they turned to the humble beauty of the local countryside, seeking to depict nature with honesty and emotional resonance. Key figures included Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Jules Dupré, Charles-François Daubigny, and Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, among others.

Troyon became closely associated with this group, particularly forming strong bonds with Dupré and Rousseau. He frequented the Barbizon area, sketching and painting alongside his contemporaries, absorbing their commitment to realism and their innovative approaches to capturing the effects of light and weather. His early Salon entries, beginning in the 1830s, primarily featured landscapes inspired by these excursions. Works from this period demonstrate his growing mastery of composition and his ability to render the textures and moods of the natural world, often depicting scenes from the Forest of Fontainebleau or the regions of Brittany and Normandy.

While respected for his landscapes, Troyon hadn't yet found the distinctive voice that would define his mature career. His paintings were well-received, earning him recognition at the Paris Salon, including medals in 1838 and 1846. However, his engagement with the Barbizon ethos, particularly its emphasis on depicting rural life and the integration of figures or animals within the landscape, laid the groundwork for his eventual, transformative shift in focus. The collaborative spirit and shared ideals of the Barbizon painters provided a fertile environment for his artistic development.

The Dutch Revelation: A Pivotal Journey

A turning point in Constant Troyon's artistic journey occurred in 1847 with a trip to the Netherlands and Belgium. This visit exposed him directly to the masterpieces of the Dutch Golden Age, particularly the works of seventeenth-century animal and landscape painters. He was profoundly struck by the paintings of artists like Paulus Potter, renowned for his incredibly lifelike depictions of cattle, and Aelbert Cuyp, celebrated for his mastery of atmospheric light, often bathing pastoral scenes in a warm, golden glow. Rembrandt van Rijn's dramatic use of light and shadow also likely left an impression.

Seeing these works firsthand was a revelation for Troyon. He admired the Dutch masters' ability to elevate humble rural subjects – cows, sheep, meadows, and skies – to the level of high art through meticulous observation and technical brilliance. Potter's detailed rendering of animal anatomy and texture, combined with Cuyp's sensitivity to light and atmosphere, offered a powerful model. Troyon recognized an opportunity to synthesize these influences with the Barbizon School's commitment to naturalism and direct observation of the French countryside.

Upon his return to France, Troyon's artistic focus shifted decisively. While he never entirely abandoned landscape, animals – particularly cattle and sheep – moved from being incidental elements to becoming the primary subjects of his most ambitious works. He began to study them with renewed intensity, focusing on their anatomy, postures, and integration within their environment. The Dutch journey provided not just inspiration but a clear direction, enabling him to develop the signature style that would bring him international acclaim as a premier animalier.

The Animalier Ascendant: Style and Technique

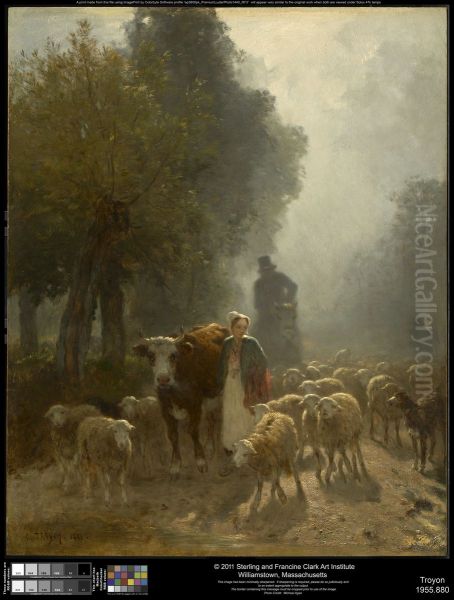

Following his Dutch sojourn, Troyon rapidly developed his distinctive approach to animal painting. His canvases became populated with robust, convincingly rendered cattle and sheep, often depicted grazing in lush pastures, being herded along country lanes, or resting under expansive skies. He moved beyond mere anatomical accuracy to capture the perceived character and presence of the animals, imbuing them with a sense of quiet dignity and grounding them firmly within their natural habitat.

His technique involved a rich application of paint, often using broad, confident brushstrokes for the landscapes and skies, contrasted with more detailed rendering for the animals themselves. He paid meticulous attention to the play of light and shadow, mastering the depiction of different times of day and weather conditions. Morning mists, the golden light of late afternoon, and the looming atmosphere before a storm were all rendered with remarkable sensitivity. This atmospheric quality, reminiscent of Cuyp, became a hallmark of his work, creating immersive and evocative scenes.

Troyon excelled at composing scenes that felt natural and unposed, yet were carefully structured for visual impact. He often used low horizons to emphasize the vastness of the sky and give prominence to the animals in the foreground. His colour palette was typically grounded in naturalistic earth tones, greens, and blues, but enlivened by skillful contrasts and subtle modulations that captured the effects of light on different surfaces – the rough texture of bark, the soft fleece of sheep, the glossy hides of cattle. He became known, as noted in the provided text, as perhaps the first French painter to depict animals with such convincing, unidealized realism in their postures and movements.

Masterworks and Recognition

Troyon's shift towards animal painting proved immensely successful, catapulting him to the forefront of the French art world. His works became highly sought after by collectors both in France and internationally, particularly in Britain and the United States. The Paris Salon became a regular venue for his triumphs.

One of his most celebrated paintings is Going to Market on a Misty Morning (also known simply as Going to Market), exhibited at the Salon of 1856 (though some sources date it slightly earlier or later, its Salon success is key). This large canvas masterfully combines landscape and animal painting, depicting peasants driving cattle and sheep along a muddy road shrouded in early morning mist. The atmospheric effects are superb, and the animals are rendered with characteristic solidity and realism. The work was highly praised and notably purchased by Emperor Napoleon III himself, cementing Troyon's status.

Other significant works showcase the breadth of his talent within his chosen specialty. The Herd of Cattle (various versions exist, a prominent one often cited) exemplifies his ability to depict groups of animals interacting naturally within a landscape setting. The Road in the Forest, likely representing his earlier landscape focus but perhaps incorporating animals, highlights his Barbizon roots. Pasture in Normandy (Art Institute of Chicago) captures the lushness of the region's farmland, populated by his signature cattle. The Storm is Coming demonstrates his skill in rendering dramatic weather effects and the animals' reactions to the changing elements.

His success was formally recognized with numerous accolades. He received multiple medals at the Paris Salon throughout his career. In 1849, he was awarded the prestigious Legion of Honour. A crowning achievement came at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1855, where he won a first-class medal, placing him among the elite artists of his generation. Today, his works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Clark Art Institute, among many others.

Interactions with Contemporaries

As a prominent member of the Barbizon School and a successful Salon painter, Constant Troyon moved within a vibrant artistic milieu and interacted with many leading figures of the day. His close association with the core Barbizon group – Théodore Rousseau, Jules Dupré, Charles-François Daubigny, Jean-François Millet – was fundamental. They shared sketching trips, exhibition strategies, and a collective push against academic conservatism. Daubigny, known for his river landscapes often painted from his studio boat, shared Troyon's commitment to capturing specific light and weather effects. Millet, focused on the human figure within the rural landscape, complemented Troyon's focus on the animal world, together painting a comprehensive picture of peasant life. Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, another giant associated with Barbizon, though often maintaining a more poetic style, was also part of this broader circle.

Troyon also crossed paths with Gustave Courbet, the provocative leader of the Realist movement. Evidence suggests they interacted, particularly around Le Havre in the late 1850s or early 1860s. While their styles differed – Courbet's realism often carried a more overt social or political edge – they shared a commitment to depicting the tangible world without idealization. Troyon reportedly even collaborated with Courbet on certain works, potentially adding animals to Courbet's landscapes, although the extent of this is debated.

Perhaps one of Troyon's most significant interactions involved the young Claude Monet. Around 1859, Monet, then an aspiring artist from Le Havre known for his caricatures, sought advice in Paris. Troyon, recognizing Monet's potential but perhaps finding his initial attempts lacking discipline, famously advised him to study drawing diligently and recommended he learn from established painters. Sources suggest Troyon pointed Monet towards artists like Courbet and, crucially, Eugène Boudin. Boudin, a fellow painter from Normandy known for his luminous beach scenes and skies, became a vital mentor to Monet, encouraging him to paint outdoors and capture fleeting effects of light – advice that aligned with Troyon's own Barbizon-influenced practices and proved foundational for Monet's development towards Impressionism. Troyon's willingness to guide younger talent highlights his standing in the art community.

Teaching and Influence

While not known for running a large, formal atelier in the manner of some academic painters, Constant Troyon did impart his knowledge and influence younger artists. His most clearly documented student was Evariste-Vital Luminais, a painter who would later become known for his historical scenes, particularly those depicting Merovingian history. Luminais received training from Troyon, likely focusing on landscape and potentially animal painting, before developing his own distinct specialization. The mention of Léon Adolphe Belly as a student is less certain; he was influenced by Barbizon figures like Rousseau and may have interacted with Troyon, but direct tutelage is not definitively established.

Troyon's primary influence, however, extended far beyond direct studentship. His immense success and distinctive style made him a model for subsequent generations of landscape and animal painters across Europe. His ability to combine realistic depiction with atmospheric sensitivity resonated widely. In France, his work informed later Barbizon-influenced painters and arguably contributed to the Impressionists' interest in capturing specific light conditions, even if their techniques diverged. Artists like Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley, while forging their own paths, inherited the Barbizon commitment to landscape that Troyon championed.

His impact was particularly strong among painters specializing in animals or rural scenes. In the Netherlands, artists like Anton Mauve, a leading figure of the Hague School and a cousin-in-law and early influence on Vincent van Gogh, clearly drew inspiration from Troyon's pastoral subjects and atmospheric handling. Belgian painters such as Emile Claus also showed affinities with Troyon's approach to light and rural life. The enduring popularity of his subjects and style ensured his work was widely studied and emulated. After his death, his mother established the Troyon Prize, awarded through the École des Beaux-Arts, to encourage and recognize excellence in animal painting, further cementing his legacy in this genre.

Later Years and Declining Health

Despite achieving remarkable success and international fame, Constant Troyon's later years were marked by tragedy. By the early 1860s, his health began to deteriorate significantly. Contemporary accounts suggest he suffered from mental health issues, described at the time as a "mental disorder" or "nervous breakdown." This condition progressively worsened, impacting his ability to work and engage with the world.

Sources indicate that by 1863 or 1864, his mental state had declined to the point where he required care and was largely incapacitated. This effectively brought his prolific artistic production to an end. The exact nature of his illness remains unclear from a modern diagnostic perspective, but its effects were devastating.

Constant Troyon died in Paris on February 21, 1865, at the relatively young age of 54. His passing was mourned by the French art community, who recognized the loss of a major talent. Reflecting his high standing, his funeral was reportedly sponsored by Emperor Napoleon III, the same patron who had acquired one of his most famous paintings. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery in Paris. Having never married and leaving no children, his direct line ended with him, but his artistic legacy was already firmly secured.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Constant Troyon occupies a secure and respected place in the history of nineteenth-century French art. He is primarily remembered as one of the leading figures of the Barbizon School and, arguably, the most successful and influential animal painter of his generation in France. His unique contribution lies in his ability to synthesize the Barbizon commitment to naturalistic landscape with a specialized focus on depicting domestic animals, particularly cattle and sheep, elevating them to principal subjects imbued with dignity and presence.

His work bridged the gap between pure landscape and genre painting. Influenced by the Dutch masters yet firmly rooted in his observation of the French countryside, he created canvases that were both realistic and deeply atmospheric. His mastery of light, his robust brushwork, and his empathetic portrayal of animals set a standard that influenced painters across Europe. While Impressionism would soon revolutionize the depiction of light and landscape, Troyon's achievements within the framework of Barbizon realism remain significant. He demonstrated that scenes of humble rural life could possess profound beauty and artistic merit.

His popularity during his lifetime was immense, commanding high prices and earning prestigious awards. While artistic tastes shifted after his death, his reputation endured, particularly among collectors who appreciated pastoral scenes and animal subjects. His works remain staples in major museum collections, valued for their technical skill, historical importance within the Barbizon movement, and their evocative portrayal of a pre-industrial rural world. He successfully carved out a distinct identity within a generation of remarkable landscape painters, ensuring his enduring legacy as the master of bovine majesty and Barbizon light.

Conclusion

Constant Troyon's artistic career traces a compelling arc from the workshops of Sèvres to the forefront of the international art market. As a key member of the Barbizon School, he initially dedicated himself to the realistic depiction of the French landscape. However, inspired by the Dutch Golden Age, he found his true calling in animal painting, becoming the preeminent animalier of his time. His canvases, celebrated for their naturalism, atmospheric depth, and empathetic portrayal of cattle and sheep within idyllic pastoral settings, earned him widespread acclaim, prestigious awards, and the patronage of Emperor Napoleon III. Through his interactions with contemporaries like Courbet and Daubigny, and his guidance to younger artists like Monet, Troyon played an active role in the vibrant art world of nineteenth-century France. Despite a tragic decline in health later in life, his legacy endures through his influential style and his masterworks housed in museums globally, securing his position as a pivotal figure in the transition towards modern landscape and animal painting.