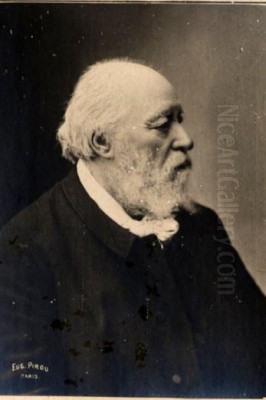

François-Louis Français stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of nineteenth-century French art. Born in Plombières-les-Bains in the Vosges region on November 17, 1814, and passing away in Paris on May 28, 1897, his long and productive career spanned a period of profound transformation in European painting. Primarily celebrated as a landscape painter, Français navigated the currents of Realism and the enduring legacy of Neoclassicism, forging a distinct path characterized by sensitivity to light, atmospheric nuance, and a deep affection for the natural world, particularly the environs of Paris and the forests of Fontainebleau. While often associated with the Barbizon School, his work retains a unique clarity and compositional elegance that sets it apart.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Français's journey into the art world was not one of privilege or immediate immersion. His origins were modest; his father was a former customs official. At the age of fifteen, the young Français found himself working, initially as an office clerk. However, the pull towards art was strong. He soon found employment at a bookstore, a position that perhaps offered closer proximity to the world of images and illustration. This period was marked by necessity and self-reliance, forcing him to cultivate his burgeoning talent largely through his own efforts and observation.

Seeking formal training and opportunity, Français made the pivotal move to Paris. The capital was the undeniable center of the French art world, offering access to museums, salons, and studios. He initially entered the workshop of Jean Gigoux, a painter and illustrator known for historical subjects and portraits. While Gigoux provided foundational instruction, it was Français's encounter and subsequent relationship with Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot that would prove most formative for his landscape painting.

The Influence of Corot and the Barbizon Spirit

The meeting with Camille Corot (1796-1875) marked a turning point. Corot, already an established and deeply respected figure, became both a mentor and a friend. Français deeply admired Corot's ability to capture the subtle poetry of nature, his mastery of tonal values, and his increasingly lyrical approach to landscape. Corot's influence is palpable in Français's handling of light and his preference for silvery, harmonious palettes, particularly in his earlier works. However, Français was no mere imitator; he absorbed Corot's lessons while developing his own distinct artistic voice.

Français worked during the ascendancy of the Barbizon School, a loose collective of artists who rejected the idealized, historical landscapes favored by the Academy and instead sought truth and authenticity through direct observation of nature. Centered around the village of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau, painters like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, Constant Troyon, and Jules Dupré championed a more realistic and often rustic depiction of the French countryside.

While Français shared their commitment to painting from nature and often depicted similar locales, his style generally retained a greater degree of finish and compositional structure than some of the more rugged Barbizon painters. His work often feels less overtly 'Realist' in the vein of Gustave Courbet and more aligned with a poetic naturalism, balancing observed detail with an underlying sense of harmony and tranquility, echoing Corot's unique blend of classicism and naturalism. He captured the specific character of places but imbued them with a gentle, often luminous, atmosphere.

Salon Success and Official Recognition

The Paris Salon, the official exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage in nineteenth-century France. Français made his Salon debut in 1837 with a landscape titled Sous les saules (Under the Willows), featuring figures painted by his friend Henri Baron. This marked the beginning of a long and successful relationship with the institution. He became a regular and respected exhibitor for decades.

His talent did not go unnoticed. In 1848, a year of significant political upheaval in France, Français received a prestigious first-class medal at the Salon for works including Le Soleil Couchant (The Setting Sun). This award solidified his reputation as a leading landscape painter of his generation. Further accolades followed, demonstrating his standing within the official art establishment.

He was awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour) in 1853, a significant mark of distinction. His status was further elevated when he was promoted to Officier de la Légion d'honneur (Officer of the Legion of Honour) in 1867. Culminating his official recognition, Français was elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1890, taking the seat previously held by the painter Ernest Hébert. This election confirmed his position as a respected master within the French artistic hierarchy.

Artistic Style: Light, Atmosphere, and Composition

The defining characteristic of François-Louis Français's art is his masterful handling of light and atmosphere. He possessed an exceptional ability to render the subtle variations of daylight, from the crisp clarity of morning to the soft glow of twilight. His skies are never mere backdrops but active participants in the scene, filled with nuanced cloud formations and suffused with light that filters through foliage or reflects off water surfaces.

His brushwork, while precise, often displays a certain lightness of touch, particularly in the rendering of leaves and grasses. Compared to the sometimes heavy impasto of Courbet or the broader strokes of Daubigny, Français maintained a balance between descriptive detail and overall atmospheric effect. He built his compositions carefully, often employing traditional landscape structures – framing trees, receding planes, a balance of light and shadow – but always adapted to the specific character of the chosen scene.

His subjects were drawn primarily from the French landscape. The forests of Fontainebleau, the riverbanks of the Seine and Oise, the parks around Paris, and the countryside of the Vosges region near his birthplace provided ample inspiration. He excelled at depicting woodland interiors, tranquil river scenes, and pastoral vistas, often populated with small, unobtrusive figures that enhance the sense of scale and provide a touch of human presence within the grandeur of nature. His work evokes a sense of peace and contemplative beauty.

The Italian Sojourn

Like many artists of his era, including his mentor Corot, Français felt the allure of Italy. He traveled and worked there, particularly around Rome and its environs. This experience, common for artists seeking to connect with the classical tradition and experience the unique quality of Mediterranean light, had a noticeable impact on his work.

His Italian landscapes often exhibit a brighter, warmer palette compared to his more northern French scenes. The intense Italian sunlight encouraged a bolder use of color and stronger contrasts. Works such as View of the Villa Medici, Rome showcase his ability to adapt his style to different climes and historical settings, capturing the distinctive architecture and vegetation under a brilliant sky. This period added another dimension to his oeuvre, demonstrating his versatility and his engagement with the long tradition of European landscape painting rooted in the Italian experience, harking back to masters like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin.

Mastery of Light and Atmosphere: A Deeper Look

Français's preoccupation with light connects him to a long lineage of landscape painters, yet his approach was distinctly of his time. He moved beyond the generalized light of Neoclassical landscapes and sought to capture specific, observed effects. His work predates the Impressionists' scientific analysis of light and color, but it shares a profound interest in transient atmospheric conditions. One can see parallels with the atmospheric concerns of English painters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, though Français's temperament led him towards more serene and less dramatic interpretations.

He excelled at depicting the interplay of light and shadow within forests, the dappled sunlight filtering through leaves onto the forest floor, or the way light reflects and refracts on the surface of water. His paintings often capture a particular time of day or weather condition with remarkable fidelity – the hazy light of an autumn afternoon, the cool clarity after a rain shower, the golden glow of sunset. This sensitivity makes his landscapes immersive and emotionally resonant, inviting the viewer to share in a moment of quiet contemplation of the natural world. He wasn't just painting trees and rivers; he was painting the air and the light that surrounded them.

Français as an Illustrator

Beyond his significant achievements as a painter, François-Louis Français was also a highly accomplished and prolific illustrator, particularly skilled in wood engraving. In the mid-nineteenth century, illustrated books and journals were immensely popular, and engraving was a crucial medium for disseminating images to a wide audience. Français brought the same sensitivity and technical skill evident in his paintings to his graphic work.

He contributed illustrations to numerous important publications, including editions of classic French literature and contemporary works. Notably, he collaborated with other artists on large illustrative projects. His work appeared alongside that of figures like Henri Baron (who had painted figures in his Salon debut piece), Célestin Nanteuil, and Octave Tassaert. This aspect of his career highlights his versatility and his engagement with the broader visual culture of his time. His illustrations often depicted landscapes and rustic scenes, translating his painterly concerns into the linear medium of engraving with remarkable success.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into His World

While a comprehensive list is vast, several key works exemplify Français's style and thematic concerns:

Orpheus (1863, Musée d'Orsay, Paris): This large painting, depicting the mythical poet charming animals with his music in a lush, idealized landscape, demonstrates Français's ability to handle mythological subjects within a naturalistic setting. The treatment of the dense foliage and the soft, diffused light is characteristic.

The End of Winter (1853, Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille): Capturing the transitional moment when snow begins to melt and nature reawakens, this work showcases his sensitivity to seasonal change and atmospheric nuance. The cool light and bare trees convey the lingering chill, while hints of green suggest the coming spring.

Daphnis and Chloe (Salon of 1872): Another mythological subject set within a meticulously rendered landscape, showing his continued engagement with classical themes integrated into his naturalistic style.

View near Paris or Environs of Paris (various examples): Many of his most beloved works depict the familiar landscapes accessible from the capital – the Seine, the Marne, the forests of Saint-Cloud or Meudon. These paintings capture the gentle beauty of the Île-de-France region with affection and precision.

View of the Villa Medici, Rome: Representative of his Italian period, showcasing the brighter palette and architectural focus inspired by his travels.

Sous les saules (Under the Willows) (1837): His Salon debut piece, significant for launching his public career.

Le Ruisseau de Neuf-Pré (The Stream at Neuf-Pré): A typical example of his intimate forest stream scenes, focusing on reflections, rocks, and foliage.

These works, among many others, reveal an artist consistently dedicated to capturing the beauty and tranquility of the natural world through careful observation and a refined technique.

Context within 19th-Century French Art

Français's career unfolded against a backdrop of intense artistic debate and innovation. He emerged when Romanticism, championed by Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault, was challenging the dominance of Neoclassicism (Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres). He matured alongside the rise of Realism, spearheaded by Gustave Courbet, which advocated for the depiction of ordinary life and unidealized nature.

Français occupied a space somewhat between the established traditions and the emerging avant-garde. He embraced the Barbizon School's focus on direct observation but maintained a level of compositional harmony and finish rooted in older traditions. He was highly successful within the Salon system at a time when it was increasingly being challenged by independent artists.

When Impressionism burst onto the scene in the 1870s, with artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley revolutionizing the depiction of light and modern life, Français remained committed to his own established style. While the Impressionists dissolved form in favor of capturing fleeting moments of light and color, Français retained a clearer structure and more detailed rendering. He represented a form of landscape painting that was deeply respected and widely popular, even as more radical approaches gained momentum. His contemporaries included historical painters like Paul Delaroche and Orientalists, adding to the diverse artistic landscape of the era.

Later Career and Legacy

François-Louis Français remained active and respected throughout his long life. His election to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1890, at the age of 76, was a testament to his enduring reputation and the esteem in which he was held by the official art world. He continued to paint and exhibit, staying true to the vision he had cultivated over decades.

Upon his death in Paris in 1897, he was recognized as one of the foremost landscape painters of his generation. His hometown of Plombières-les-Bains honored its native son by establishing a museum dedicated to his work, the Musée Louis Français, ensuring his legacy in the region that first inspired him.

Today, Français's work might be less revolutionary in hindsight than that of the Impressionists or even the core Barbizon figures like Rousseau or Millet. However, his paintings retain a powerful appeal. They offer meticulously crafted, deeply felt visions of nature, characterized by tranquility, luminosity, and technical brilliance. His mastery of light and atmosphere remains compelling, and his works provide a valuable perspective on the evolution of French landscape painting in the nineteenth century. His paintings can be found in major museums, including the Louvre and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, as well as numerous regional museums throughout France and collections internationally. He stands as a master of poetic naturalism, an artist who found profound beauty in the quiet corners of the French countryside and rendered them with enduring skill and sensitivity.

Conclusion

François-Louis Français carved a distinguished path through the dynamic landscape of nineteenth-century French art. From humble beginnings and self-directed study, he rose to become a celebrated landscape painter, honored by the Salon and elected to the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Deeply influenced by Corot yet developing his own distinct style, he excelled at capturing the subtle interplay of light and atmosphere in nature. His depictions of the forests, rivers, and fields of France, as well as his luminous Italian scenes, are characterized by careful composition, technical finesse, and a pervasive sense of tranquility. While associated with the Barbizon spirit of direct observation, his work retained an elegance and finish that ensured his success within the established art world. As both a painter and a skilled illustrator, Français left a significant body of work that continues to charm viewers with its serene beauty and masterful rendering of the natural world.