Jean Hippolyte Marchand stands as a significant, though sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant landscape of early 20th-century French art. Born in Paris in 1883 and passing away in 1940, Marchand navigated the complex currents of artistic change, developing a style that synthesized elements of Post-Impressionism and Cubism, while also engaging with printmaking and illustration. His connections with key figures and movements, particularly in France and Britain, place him at an interesting intersection of artistic exchange during a period of radical transformation.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Jean Hippolyte Marchand's artistic journey began in the heart of the French art world, Paris. His formal training took place at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic tradition in France. From 1902 to 1906, he studied under the tutelage of Léon Bonnat, a highly respected painter known for his portraiture and adherence to classical principles. This education provided Marchand with a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and traditional techniques, a foundation evident even in his later, more modern works.

However, the artistic atmosphere in Paris at the turn of the century was electric with innovation. While Bonnat represented the established order, movements like Impressionism had already revolutionized painting, and Post-Impressionism, led by giants such as Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh, was pushing artistic boundaries further. Fauvism exploded onto the scene in 1905, and Cubism was beginning to germinate in the studios of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Marchand absorbed these influences, gradually moving away from strict academicism towards a more personal and modern form of expression.

Emergence into the Avant-Garde: The London Connection

Marchand's emergence onto the international stage was significantly facilitated by the English art critic and painter Roger Fry. Fry was a pivotal figure in introducing modern French art to a skeptical British audience. In 1910, he organized the groundbreaking exhibition "Manet and the Post-Impressionists" at the Grafton Galleries in London. This exhibition, which included works by Manet, Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, and others, caused a sensation and provoked outrage among conservative critics but galvanized younger artists and collectors.

Jean Hippolyte Marchand was among the contemporary French artists featured in this landmark 1910 exhibition. His inclusion signaled Fry's belief in his talent and his relevance to the Post-Impressionist lineage. One of Marchand's works shown was the significant Still Life with Bananas. The painting demonstrated his engagement with Post-Impressionist principles, particularly the structural concerns and simplified forms reminiscent of Cézanne, combined with a distinct solidity and clarity.

The positive reception of Marchand's work, at least within avant-garde circles, led to his inclusion in Fry's second major exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in 1912, organized with fellow critic Clive Bell. This "Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition" further solidified Marchand's reputation in Britain and strengthened his ties with Fry, Bell, and the influential Bloomsbury Group, a circle of English writers, intellectuals, and artists who championed modern art and ideas.

Artistic Style: Synthesizing Influences

Marchand's artistic style is often characterized by its thoughtful synthesis of various influences. While rooted in the observational tradition learned at the École des Beaux-Arts, his work clearly embraces the structural and formal innovations of Post-Impressionism. The influence of Paul Cézanne is particularly palpable in his landscapes and still lifes, evident in the way he constructs forms through planes of colour and emphasizes underlying geometric structures.

His work from the 1910s shows a clear engagement with Cubism, though perhaps a more restrained and less fragmented version than that practiced by Picasso or Braque. Critics like Roger Fry and Clive Bell admired the "architectural" quality and logical construction in Marchand's paintings. They saw in his work a continuation of the classical French tradition, albeit expressed in a modern idiom. This perceived balance between modernity and tradition, structure and representation, appealed greatly to the Bloomsbury aesthetic.

While sometimes labeled simply as a Cubist, Marchand's style retained a strong connection to representation and naturalism. He did not dissolve objects into near abstraction but rather simplified and solidified them, exploring their volume and presence within a carefully composed space. This approach aligns him with other artists associated with the Salon Cubists or the Section d'Or group, such as Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, who sought a more ordered and sometimes decorative form of Cubism compared to the analytical explorations of Picasso and Braque. Later in his career, some works suggest a move towards a form of Neoclassicism, a "return to order" seen in the work of many former avant-gardists after World War I.

Representative Works and Achievements

Still Life with Bananas (c. 1910) remains one of Marchand's most recognized works, largely due to its exhibition history in London and its connection to the Bloomsbury Group. The painting exemplifies his style during this crucial period: solid, clearly defined forms, a muted but rich palette, and a strong sense of composition influenced by Cézanne. Its acquisition by members of the Bloomsbury circle underscores its importance in the narrative of British modernism. The work was later acquired by the prominent collector Samuel Courtauld, whose collection forms the core of the Courtauld Gallery in London.

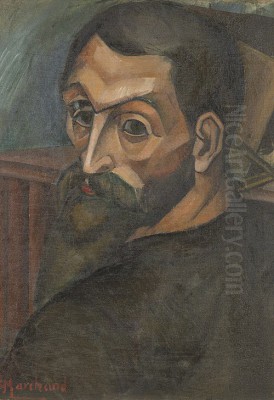

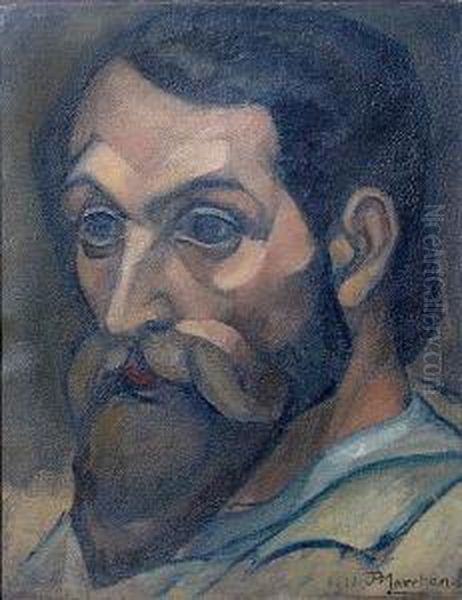

Another significant work is his Self Portrait (c. 1909-1912). This painting, now housed in the Tate collection in London (likely acquired through the Museum Works of Art Fund or similar mechanism), offers insight into the artist's persona and his stylistic concerns during his formative modern period. It displays a similar solidity and thoughtful construction found in his still lifes, rendered with a directness and psychological presence.

Beyond oil painting, Marchand was also a skilled printmaker and illustrator. He produced woodcut illustrations for notable literary works, demonstrating his versatility across media. In 1927, his illustrations appeared in Paul Claudel's Le Chemin de Croix (The Way of the Cross) and Paul Valéry's Le Serpent (The Serpent). These graphic works often display a bold simplification of form and a strong sense of design, complementing the texts they accompany.

Connections and Artistic Circles

Marchand was well-connected within the artistic and intellectual circles of his time, both in Paris and London. His association with Roger Fry and Clive Bell was crucial for his British reputation. Through Fry's social gatherings, often held in Parisian cafés, Marchand likely encountered a wide range of artists. The sources mention connections with figures like the aging Impressionist master Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and key figures of Fauvism and early Cubism such as André Derain and Georges Braque.

His participation in major Parisian Salons further integrated him into the French art scene. He exhibited at the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants, two major venues for avant-garde art in the early 20th century. His participation in the Salon des Indépendants in 1913 marked his first successful sale of a painting at such an event. He was also associated with the Section d'Or group, which held a major exhibition in 1912, showcasing artists exploring various facets of Cubism.

The Bloomsbury Group connection remained important. Artists within the group, such as Vanessa Bell (Clive Bell's wife and Virginia Woolf's sister) and Duncan Grant, were certainly aware of his work, promoted as it was by Fry and Bell. His paintings were appreciated for embodying the formal qualities – significant form, structure, harmony – that Clive Bell championed in his influential book Art (1914). The patronage of Samuel Courtauld further cemented his place in important British collections.

Printmaking and Illustration: Expanding Horizons

Marchand's activities as a printmaker and illustrator deserve specific attention, as they showcase another dimension of his artistic talent. Woodcut, a medium revived by artists like Gauguin, offered a means of achieving bold contrasts and simplified forms, aligning well with modernist aesthetics. His choice to illustrate works by prominent contemporary writers like Paul Claudel and Paul Valéry indicates his engagement with the literary avant-garde as well.

His illustrations for Claudel's Le Chemin de Croix, a religious text, likely required a different sensibility than his more secular paintings, perhaps demanding a certain gravitas and emotional depth expressed through stark black and white forms. Illustrating Valéry's dense and symbolic poem Le Serpent would have presented its own challenges, requiring visual interpretations of complex philosophical themes. This work highlights Marchand's intellectual engagement and his ability to adapt his style to different contexts and media.

Later Career, Legacy, and Anecdotes

Information about Marchand's later career, particularly after the 1920s, is less prominent than details about his breakthrough period. He continued to work and exhibit, but perhaps without the same level of international attention he received through the London Post-Impressionist shows. His style likely continued to evolve, potentially embracing the "return to order" Neoclassicism seen in the work of Picasso, Derain, and others in the interwar period.

Unlike some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, there are few specific "interesting life events" or colourful anecdotes widely recorded about Jean Hippolyte Marchand himself. Searches often yield information about other individuals named Marchand from different eras or fields. His significance lies primarily in his artistic output and his role within specific art historical contexts, rather than in a dramatic personal biography. He appears to have been a dedicated artist, recognized by influential critics and collectors, who contributed thoughtfully to the dialogue between tradition and modernity.

His legacy rests on his position as a talented painter and printmaker who successfully navigated the transition from academic training to modern art. He was a key figure in the dissemination of French Post-Impressionist and Cubist ideas in Britain, thanks to his association with Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury Group. His work is valued for its structural integrity, its synthesis of Cézannian principles with Cubist sensibilities, and its inherent connection to the French tradition of clarity and order. While perhaps not as revolutionary as Picasso, Braque, or Matisse, Marchand represents an important strand of modern art that sought to reconcile innovation with enduring artistic values.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Jean Hippolyte Marchand occupies a distinct and respectable place in the history of early 20th-century art. As a painter, printmaker, and illustrator, he demonstrated technical skill and intellectual depth. His education under Léon Bonnat provided a firm base, but his true contribution lies in his engagement with Post-Impressionism, particularly the legacy of Cézanne, and his thoughtful incorporation of Cubist principles.

His role as a bridge figure is notable – bridging academic training and modernism, linking the Parisian avant-garde with the burgeoning modern art scene in London through his crucial participation in Roger Fry's exhibitions, and connecting with influential circles like the Bloomsbury Group and collectors like Samuel Courtauld. Works like Still Life with Bananas and his Self Portrait, along with his illustrations for Claudel and Valéry, attest to a consistent artistic vision characterized by structure, clarity, and a sensitive engagement with form and representation. Though lacking sensational anecdotes, Jean Hippolyte Marchand's career reflects a dedicated artistic journey that contributed significantly to the complex tapestry of European modernism.